Share of citizen energy in decline as funding runs out and big investors take over

1 January 2021 marked the beginning of the end of a key phase in Germany’s Energiewende. On this date, the pioneers of Germany’s energy transition stopped receiving the feed-in tariff that, for the last 20 years, has guaranteed them a fixed price for generating electricity via wind, solar or biomass.

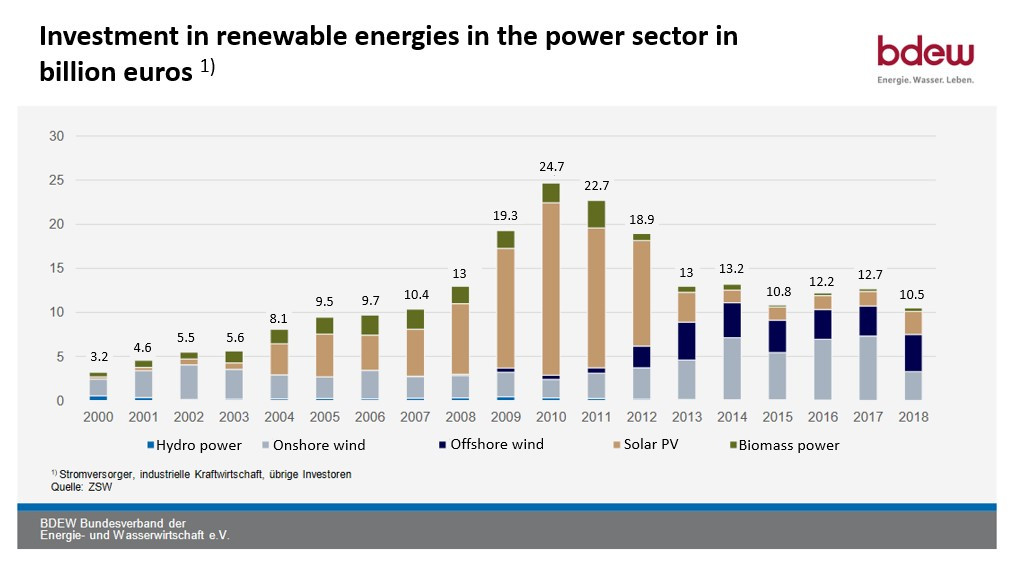

Feed-in payments for renewable power were introduced with the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) in the year 2000 and enabled Germany’s renewables boom. According to the authors of Energy Democracy, Craig Morris and Arne Jungjohann, more than 1 GW of onshore wind capacity was installed in the first year of the feed-in policy, and by 2002 it had risen to 3.2 GW. This amounted to a third of global wind production capacity at the time. Solar installations also proliferated at a phenomenal rate and, by 2007, Germany was producing 45 percent of the world’s solar electricity. By 2013, 5 GW of power generators fuelled by biomass were in operation.

Many of the early adopters of renewable energy production were groups of ordinary citizens who invested in local citizen wind parks (Bürgerwindparks) near their villages or put solar panels on their roofs. Often, their motive wasn’t (only) receiving the feed-in payments but also the opportunity to participate in a decentralised, more democratically organised power system, independent of the major utilities that traditionally owned the large coal and nuclear power plants that dominated the market.

With fixed payments to many of these pioneers and their followers ending in the next few years and big utilities becoming more and more firmly established in green energy generation, citizen energy proponents are worried that their quick rise to success may have an early demise. Marco Gütle of the citizen energy project association Bündnis Bürgerenergie predicts that a significant number of plants currently supported by the EEG across all renewable sectors are in danger of closure.

He has grounds for pessimism: Citizen participation in the Energiewende is already in decline. In 2014, a survey commissioned by the group found that more than half of green electricity was being generated by citizens. By the beginning of 2021, the share of citizen-generated energy had fallen to one third. Some of this shift in participation is due to the fact that the overall capacity – driven by large investors in large scale renewable installations – has also grown: From 85 GW in 2014 to 123 GW in 2020. But the question remains, what a decreasing share of citizen energy projects in the energy transition means for the overall power supply and for public acceptance of the green transformation.

In the biogas sector, 1000 plants have lost the feed-in tariff this year, out of a total of 9,500. In the solar sector, an estimated 128,000 small PV installations will fall out of the feed-in tariff arrangement in the years between 2020 and 2025, according to the German Solar Association (BSW). This is out of a total of 1.7 million installations in Germany.

In 2021 almost 4 gigawatts (GW) of wind power capacity has fallen out of the 20-year feed-in tariff arrangement. By the end of 2025, this will have risen to approximately 15.4 gigawatts, as successive rounds of clean energy producers come to the end of their 20-year limit. To put this in context: In February 2021, the total onshore wind energy capacity installed in Germany was 55 gigawatts.

However, the energy ministry stated that out of 3.5 GW of installed onshore wind capacity for which feed-in remuneration ended in January, only 90 megawatts (MW) had ceased production.

While the government has said that seventy percent (2.3 GW) of wind producers have not applied for follow-up funding, but have found ways to directly market their power, it is not clear that this will be an option for smaller producers. Marco Gütle of the Bündnis Bürgerenergie is worried that citizen pioneer installations will not be replaced by new citizen-owned projects. “Ultimately”, he says, “it’s a question of economics and, at the moment, the majority of green plants cannot survive on €4-5 ct/Kwh, which is the average price available at the electricity exchange.” While pioneer wind parks in good condition stand a fair chance of finding a new buyer for their electricity, the outlook for old biogas and very small solar PV installations is often more bleak.

Feed-in tariffs and citizen energy as victims of their own success

Germany’s citizen energy phenomenon reached its peak in the early 2010s, in large part thanks to the feed-in tariff. The policy aimed to incentivise the expansion of renewable energy investment by providing producers with a minimum price for their energy and a guaranteed grid connection. The price was fixed for 20 years and differed depending on the type of energy produced and the environmental conditions. Thanks to the policy, renewable energy production sped up.

As price for renewable technologies fell, the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) was overhauled in 2014, and the government decided to replace the feed-in tariffs with auctions – subjecting the maturing industry to market-based conditions. Previously, the tariffs (including their degression over time), were determined by the legislator. But the government wanted to avoid the high payment guarantees of the early renewables boom years, when solar and wind installations were much more expensive than today. Those guarantees still make up the bulk of the costs paid by consumers with their power bills. So in order to “reduce electricity costs, expand the market to a more diverse range of energy producers and maintain targets for increasing the country’s renewable energy generating capacity”, a tender scheme for all but small solar PV installations was established in 2016.

Auctions started in 2017 and have since taken place several times each year. The government stipulates the volume of the tender, power plant operators bid on the available capacity, and the cheapest bids win. All plants or projected plants of over 750 kW are encouraged to participate, but in practice this hasn’t happened. It’s too costly and bureaucratic for small citizen energy producers to compete, industry representatives have said. Instead professional wind park developers have taken over the scene – sometimes disguised as citizen projects.

Analysing the PV auction pilots between 2014 and 2016, consultancy Ecofys found that “no cooperative was visibly successful in any of the PV auctions over the last two years”. In his 2019 report “Community Energy in Germany: More Than Just Climate Mitigation”, Craig Morris, co-author of Energy Democracy, asserts that in “no country have community projects thrived once FITs were done away with”. Far from promoting a diversity of actors, which it claimed as a goal, the auction system has so far replaced one set of actors (citizens) with another (big firms).

Casimir Lorenz of Aurora Energy Research (which offers analysis and consultancy to investors in the energy transition) argues that it isn’t the changes to the EEG but the professionalisation of the industry that is inevitably shutting out smaller players. This is particularly the case for onshore wind and, to a lesser extent, PV, because the limited availability of land means that competition for space is increasingly high and renewable developers therefore have to be fast and efficient. In particular established municipal utilities and large energy companies are investing, e.g. Munich’s SWM wants to invest tens of millions in 12 solar PV parks in four years and utility EnBW is establishing Germany’s largest solar PV park which will operate without state funding. European energy companies have announced major renewable investments, reaching up to 1 trillion euros by 2030.

Renewable energy can boom without citizen involvement but risks losing public support

There is disagreement on the consequences and costs of the decline in citizen participation. Casimir Lorenz accepts that reduced participation is threatening public support especially for wind but argues that citizens can be engaged in the energy transition without necessarily being producers themselves. One strategy is to pay citizens a so-called “wind power euro” for agreeing to allow wind turbines to be built near their homes.

Dieter Fries, who sits on the board of Bundesverband Windenergie (BWE) and is himself a pioneer, believes that small-scale producers like him laid the path for industry to follow. Now that big players are competing to enter the renewables market, he sees the fruits of their efforts on the horizon: an energy market dominated by renewables.

A report and survey commissioned by energy industry association BDEW found that even with larger investors taking over, up to two thirds of the gross value added by investments in local energy infrastructure and production remain in the German state where the investment takes place. Up to one fifth of the investment remains in the region where wind parks, solar PV installations, charging stations or production of climate-neutral gases are established.

Volker Quaschning, professor of renewable energy systems at the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin, says that “Germany cannot fulfil its part of the Paris Agreement without citizen participation.” The fulfilment of its climate targets requires Germany to increase renewable installations by a factor of 4 or 5 each year, he says. “German households hold 6.7 trillion euros in savings; these funds must be tapped in order to ensure the success of the Energiewende,” Quaschning argues.

And Quaschning believes some kind of feed-in mechanism is needed to restart onshore wind construction. Difficult licensing procedures due to red tape, environmental considerations and protests by local residents all have contributed to bring expansion to the lowest level in 20 years in 2019. Although numbers went up again in 2020, the expansion of onshore wind capacity is still behind the envisaged targets.

The EU has sanctioned the development of small wind parks outside the tendering system as part of its efforts to promote community energy; Quaschning says all the German government has to do now is act.

Deeper benefits of citizen participation

Beyond acceptance and funding, Marco Gütle says there are other reasons to encourage community participation in the Energiewende: Participation promotes democratic values, strengthens communities and boosts local economies.

In the AEE Community Renewables Podcast, Melanie Ball, a member of the women’s cooperative Windfang, makes the case for a different kind of economy represented by community energy. “the energy transition should be a transition from one system to another […] if it’s the big companies that just change their portfolio of what kind of power plant they are building it’s not the idea of the energy transition.”