What does the coalition deal mean for renewables, coal and the power market in Germany?

Renewables, renewables and more renewables

The new government coalition of Social Democrats (SPD), Green Party and Free Democrats (FDP) has increased the 2030 target share of renewable energies in the power system considerably – from 65 percent under the old government to 80 percent. At the same time, it raised the expected electricity need to 680-750 terawatt-hours in that year; up from the previous estimated 658 TWh for 2030. “Raising the renewables target to 80 percent is a big thing, increasing it to 70 percent would have already been considered ambitious,” Hanns Koenig from consultancy Aurora Energy Research said at a web event in December.

The main drivers of a higher than previously anticipated power demand are the new government targets of 15 million fully electric passenger cars on Germany’s roads by 2030 and an increased capacity of electrolysers (10 gigawatt) in the same year.

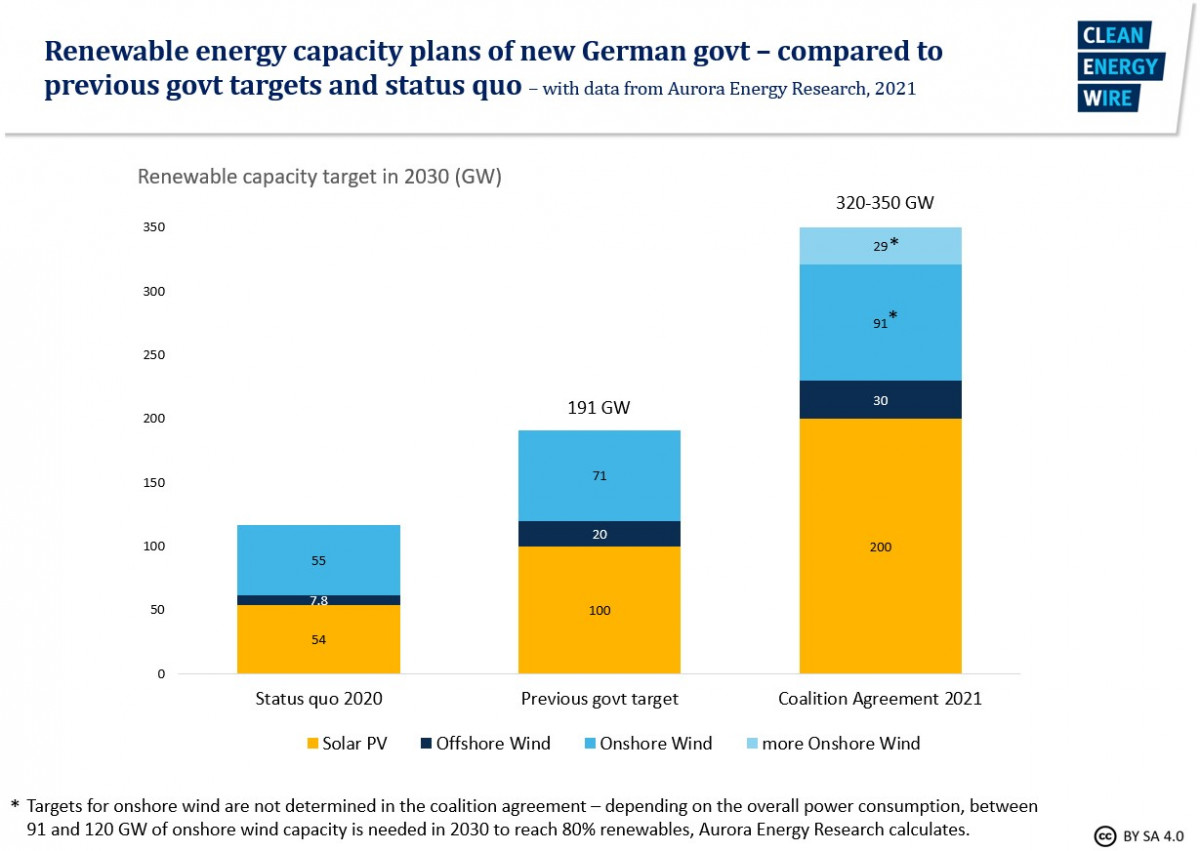

To reach the higher target and feed larger electricity demand, the government plans for much higher renewable energy capacities: There should be 200 gigawatt (GW) of solar PV and 30 GW of offshore wind installed in 2030.

To achieve these ambitious targets, Germany will need to see a net-addition of 24-28 GW of renewable capacity each year.

Annual onshore wind capacity additions will have to rise five to nine-fold, according to Aurora Energy Research, while offshore additions have to double and the solar PV sector has to add 17 GW annually.

The Institute of Energy Economics at the University of Cologne (EWI) has calculated a net annual expansion of 14.6 GW of solar PV capacity by 2030 if the targets are to be met, and notes that the highest increase recorded to date was in 2012 when 7.9 GW were added.

To make all this happen, the government will have to enable a new renewables boom.

The coalition treaty makes solar panels mandatory on every new commercial building and says they should be the “general rule” (with exceptions) on new private buildings. The target of 200 GW of solar PV in 2030 was welcomed by the solar industry as being sufficient.

Two percent of the land area in Germany is to be designated to onshore wind installations. The coalition agreement states that the idea is to get all levels of administration together, from a federal, state and local level, to find these areas and secure them with the help of the Federal Buildings Law (Baugesetzbuch). But even once this is achieved, the actual approval process for every single wind park – a procedure that has become so slow and full of administrative and legal hurdles that the average approval time has reached five to seven years – still has to be hurried along considerably.

The coalition treaty suggests that it can be done - through faster approvals, by supporting public authorities with “external project teams”, and by clarifying deadlines and requirements in application documents. The standard will be to give priority to wind parks when there are conflicts of interest, for example with species protection. The legal position of wind installations is strengthened by the coalition treaty declaring that they are considered to be “in the public interest” and serve “public security”. When deciding on the approval of a new turbine, the danger to an individual bird or bat is not going to be considered - but the overall threat to the species’ population will be. Onshore wind power expansion in Germany has slowed down markedly in the past years, not least due to many projects being challenged in court by conservationist groups or local residents on animal protection grounds.

Speaking at a web event hosted by energate messenger in December in Berlin, Ingbert Liebing, chief executive of the German Association of Local Utilities (VKU) said that the coalition treaty included all the points that had been discussed for years – they must now quickly be put into action. “Halving the approval times [for onshore wind installations] will not be enough,” he said. Considering that it was common practice to expropriate land for lignite mining, this tool should also remain a possible lever to ensure enough land for new wind turbines will be available, he said.

How to fund the “massive” renewables expansion

A massive renewables expansion will require funding. So far, the majority of renewable energy installations in Germany receive a guaranteed feed-in payment, either determined by law or by government auctions. They sell their electricity on the power market but are guaranteed a minimum remuneration per kilowatt-hour. This funding for renewables is paid for by German consumers via their power bills, in the form of a renewables surcharge that amounted to 6.5 cents per kilowatt-hour in 2021. To ease the burden on consumers and make the use of electricity more attractive compared to other energies, e.g. for charging cars or heating houses, the new government will put an end to this by 2023. As of then, renewables support will instead be paid for from the state budget, funded via the proceeds from the CO2 pricing schemes for heat and transport fuels (national ETS) and energy and industry (EU ETS).

Once the coal exit is complete, government support for renewables will be phased-out entirely, the coalition agreement states.

These plans will require a lot of additional decisions, Aurora Energy Research points out. For example, how much capacity – especially in the case of onshore wind – will be auctioned by the government in the next years, and how much added capacity will be delivered from other support schemes or power purchase agreements (PPA). How the government tackles these subjects will determine how much investment flows into renewables and how the power market as a whole will develop.

It’s good that long-term power purchase agreements feature in the coalition treaty but now the government has to do its homework because, until now, Germany has not seen a pick-up of PPAs as other countries have, Barbara Lempp, Managing Director Germany of the European Federation of Energy Traders (EFET) said at a web event by energate messenger.

With a large renewable build-out ahead there is a danger that (cheap) renewable power sources could lower prices so much that it will be difficult to phase-out subsidies with the final coal exit, Julia Breuing, of Aurora Energy Research, said. “PPAs and Guarantees of Origin might not be sufficient to ensure a market-based renewable build-out after 2030,” the researchers warn.

Who will invest? – the future power market

Additional upheaval in the power market is added by the government’s announcement to evaluate capacity mechanisms and flexibility options in the power market through a stakeholder process in 2022 – concluding with a “concrete proposal for a new power market design”.

The coalition wants the potential capacity and flexibility mechanisms to be technology-neutral and lists secured renewables capacity, highly efficient gas-fired power plants with combined heat and power generation, an innovation programme to stimulate H2-ready gas gas power plants at coal plant sites, storage facilities, energy efficiency measures, and load management as possible options.

“There will now be a two-to-three-year period where the future market design is discussed, this time of uncertainty will make investors reluctant. That’s a bit disappointing, we had hoped to see more clarity on this,” Aurora Energy Research’s Koenig said. If the government introduces a capacity mechanism, it will also have to decide if the existing power reserves (balancing reserve, capacity reserve, grid reserve) should be replaced.

Germany’s Renewable Energy Association (BEE) said that the new electricity market should give priority to flexibility components such as biogas, storage or load management over capacity markets. "With the abolition of the EEG levy on 1 January 2023, the financing of the necessary investments must be secured. Because these investments are needed," said BEE head Simone Peter in a press release.

The “ideal” coal phase-out year and the need for gas

The issue of power prices and investments is closely connected to the issue of supply security and natural gas. And this in turn has to do with the coal exit.

In 2022 (instead of 2026), the government wants to revise the current coal exit timeline which is aiming for the last plant to close down in 2038. “Ideally” the coalition partners want to bring forward the coal exit by eight years to 2030. The coalition parties make it clear that an earlier coal phase-out is necessary to reach the country’s climate targets. The parties also stress, however, that this will require not only a “massive” renewables expansion but also the construction of “modern gas power stations”, which are needed for supply security.

Analysts and energy politicians have long said that, due to increased prices in the European CO2 trading system, an earlier coal exit is very likely because the majority of coal power plants are not profitable anymore after 2030.

Between 2019 and 2030, 21 GW of lignite and 25 GW of hard coal capacity will be shuttered, the EWI says. Existing over-capacities, new flexibility options and efficiency as well as the addition of renewables capacity will mean that not the whole of this controllable power plant capacity will need to be substituted, German energy industry association BDEW says. “But an earlier coal phase-out means we will need an additional 17 GW in gas-fired capacity,” BDEW head Kerstin Andreae said.

A secure and affordable supply of electricity – particularly while it is demanded of more and more companies to switch from using fossil fuels to green electricity in their operations – is one of the German industries’ main concerns. With both nuclear and coal out as controllable power sources, industry representatives were relieved to find the coalition treaty taking a very pro natural gas approach.

Until 2045 - when Germany plans to have net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and will therefore also have to substitute fossil gas with renewable energy sources such as green hydrogen - natural gas is the accepted bridging technology. The necessary new gas turbines have to be “hydrogen ready”, the coalition treaty stipulates.

The EWI estimates that an additional 23 GW of hydrogen-ready gas plants would be necessary to enable a 2030 coal exit. The official pipeline of planned power plant additions by the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) currently holds 2.3 GW of gas capacity.

Industry representatives say that the future power market design and CO2 prices will be essential in triggering the necessary investment in new gas plants.

The future government has to create the framework for enabling the necessary natural gas and renewable build-out by creating planning security and investment security, BDEW head Kerstin Andreae said. “Companies invest when they know they can earn money.”

Meanwhile, the new minister for economy, energy and climate, Robert Habeck (Green Party), already envisages the end of the use of gas long before 2045. Natural gas “conceivably” will drop out of the country’s power mix in the 2030s, Habeck said on the day before the government was sworn in, increasing the pressure to fill the gap with renewables.

A stable electricity system

Transmission system operator Amprion has calculated that to make an earlier coal exit feasible from a system stability point of view, further updates to the grid infrastructure will be necessary. It added that part of the to-be-shut-down coal power capacities will likely have to be temporarily kept in the grid reserve, to provide back-up capacity in times of need.

The current security of supply monitoring doesn’t flag any problems until 2030, but doesn’t reflect the greater climate ambition of the government yet, Aurora Energy Research said.

If the large-scale renewables expansion comes to pass as planned, Germany will be a net exporter of electricity in 2030, the EWI calculated. It has been a net exporter for years.

The coalition wants to present a “roadmap system stability” by mid-2023 and regularly review security of supply and the rapid expansion of renewables and, to this end, turn the current monitoring of supply security into a "real stress test".

The effect on CO2 emissions

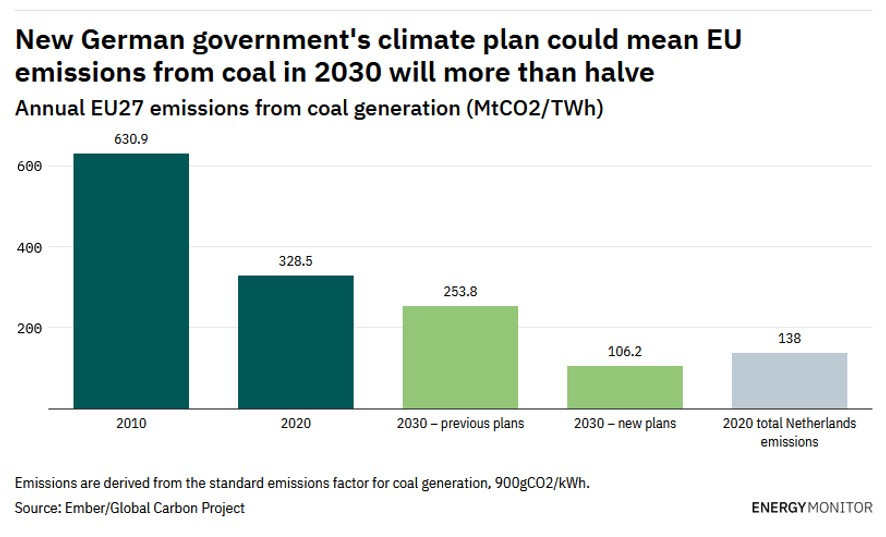

CO2 emissions from Germany’s energy sector could be more than halved as a result of the new government’s renewables expansion plans, according to calculations by the German Economic Institute (IW). If the new coalition meets its targets, 172 million metric tonnes of CO2 could be saved in relation to 2020 emissions compared to the plans of the current government, which amounted to 106 million tonnes of CO2 savings. The EWI calculates that energy sector emissions could fall from 257 million tonnes of CO2-eq (2019) to 82 million tonnes in 2030.

Think tank Ember has calculated that the new government’s climate action plan could more than halve emissions from coal in the EU in 2030.