Coming of age: How will Germany’s renewable energy pioneers fare in the free market?

For a long time, investing in and running a wind or solar park in Germany was both safe and easy: the network connection was guaranteed, green power had priority access to the grid and most importantly, every kilowatt-hour (kWh) delivered was paid for at a set feed-in remuneration, guaranteed for 20 years. This – in a nutshell – is what made Germany’s renewable energy boom of the past two decades possible.

Generous and guaranteed feed-in tariffs under Germany's Renewable Energy Act (EEG) saw the share of renewable power, mostly coming from wind, solar PV and biomass, in electricity generation rise from about 3.5 percent in 1990 to 35 percent in 2018. But as of 2021, more and more renewable installations will lose their guaranteed funding as their 20 years of EEG payments come to an end.

If all of these installations simply ceased to operate this would amount to a loss of many gigawatts of renewable capacity at a time when the government looks set to raise its ambitions in greenhouse gas reduction and wants to increase the share of renewables in power consumption to 65 percent by 2030 to pave the way for the electrification of all sectors – but struggles to meet those targets.

While this would be an unlikely worst-case scenario, experts are still worried about the uncertainty that many of the old renewable installations face. Will they be able to operate economically, banking only on a fluctuating or too low wholesale power price? Will the many operators of very small renewable installations be able to market their electricity? Will legal framework conditions be favourable to the renewable producers that enter the free market for the first time? These are just some questions that particularly Germany’s wind, solar and biogas associations but also grid operators are concerned about when looking towards the 2020s.

New business model for every individual renewable operation

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution,” Philine Derouiche, a lawyer at the German Wind Energy Association (BWE), said. The future options for old or rather “pioneer” wind parks hinge on their capacity, the condition of the turbines, their location and their operating costs, she explained. “The capability of a pioneer wind park to continue its operations on the free market primarily depends on its maintenance costs,” she told Clean Energy Wire.

Reinhard Christiansen, operator of several wind farms in Germany’s windy northern state of Schleswig-Holstein, has already gone through the motions of ensuring the future of his pioneer wind farm. As of 2021, he will sell the electricity of his six turbines in Ellhöft, with 1.3 megawatt capacity each, to power provider Greenpeace Energy. According to their contract, Greenpeace Energy will pay an agreed base price for the electricity, which is adjusted if the wholesale price on the electricity exchange should be higher.

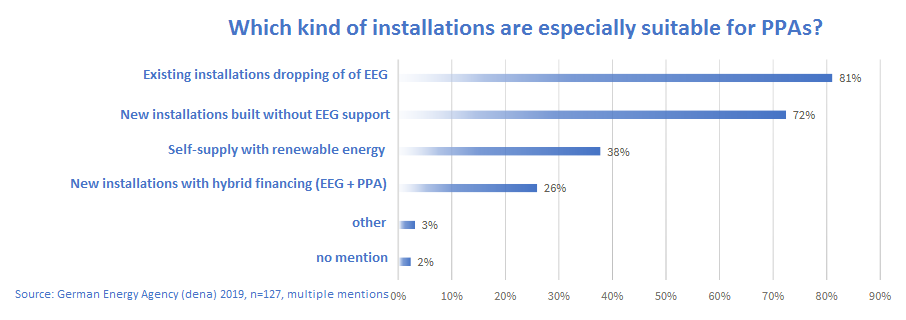

It is this kind of so-called power purchase agreements (PPA), often long-term delivery agreements, that many experts think will become the new default procedure after the feed-in tariff period ends. Under PPAs, the buyer bears the risk of weather-related fluctuations in power supply but therefore only guarantees a limited remuneration per kWh. In a survey by Germany's energy agency dena, over 85 percent of surveyed market representatives said PPAs are "important" or "very important" for the country's renewable energy future. The main reason for this was the prospect of price stability and older installations dropping out of the EEG support scheme were seen as most suitable for this purpose.

“There is a bit of a hype around PPA at the moment as electricity suppliers are positioning themselves to buy the power of renewable producers once their funding runs out,” Jan Sötebier, a lawyer at Germany’s Federal Network Agency (BNetzA), said. “This is a positive development because it means that the market works the necessary contracts out itself, without the need of new regulation.”

Of course, the EEG feed-in tariff of the past 20 years was more generous than his new agreement with Greenpeace Energy, wind operator Reinhard Christiansen said. He estimated that an existing wind park, like the one he owns, wouldn’t be able to operate with less than five eurocents per kilowatt hour (ct/kWh) - and that’s even though his turbines are in a “top condition” and he’s already made sure that he has access to the required parts if repairs become necessary.

Peter Stratmann, head of renewable energy at the BNetzA, believes that the current wholesale electricity price, which has risen from about three eurocents per kWh in 2015 to roughly five ct/kWh in 2019, can sustain most large onshore wind and solar PV farms in Germany – even including repair costs. “We now see new installations being built without any feed-in support. So, obviously, the operation of paid-for, older plants should be possible as well.” New wind parks that have won the government tenders in 2017 will receive between 3.8 and 5.7 ct/kWh.

Repowering as the prime solution

Despite PPAs being on everyone’s lips and being an indicator of renewable power becoming a fully market-proof commodity, both the BWE and the network agency BNetzA believe that there is an even better solution for old wind parks. “Where repowering is possible, operators should opt for it,” says Philine Derouiche from the BWE.

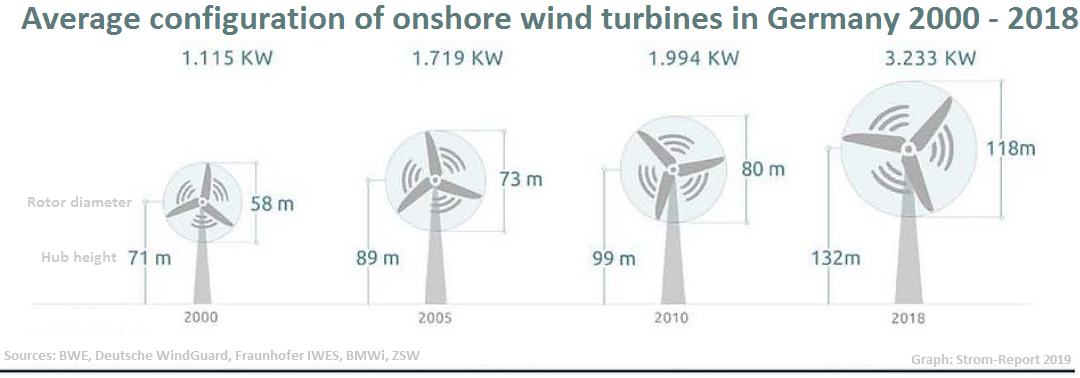

Repowering means replacing existing older wind turbines with new, more powerful ones. “Obviously, it would make sense to use the existing, and often most lucrative, wind park sites for this to maximise power production from new installations,” Jan Sötebier explains.

Since the government aims to substantially increase the share of renewables over the next decade, repowering could make an important contribution at a time when onshore wind power expansion is slowing down and at least some older wind parks will be mothballed soon. However, many states have toughened their planning laws for wind parks in the past years, including prescribing greater minimum distances between wind turbines and residential areas.

Reinhard Christiansen wouldn’t have been able to repower his wind park in Ellhöft even if he wanted to – because new turbines are considerably higher, the distance to the homes nearby wouldn’t be enough to allow permission. Wind power project consultancy Deutsche Windguard estimates that around 50 percent of today’s wind park sites will not be suitable for repowering because of changed land development plans, and another 20 to 30 percent will likely not be suitable because of new planning restrictions due to settlements or wildlife concerns. In the view of the wind park owners, this is rather unfortunate because old installations are generally scoring the highest when it comes to public acceptance as people around have got used to them over 20 years.

More creative solutions made unattractive by legal conditions

In some cases - and if repowering is not an option - using electricity from the pioneer renewable installation on site or transferring it via a direct connection to a nearby consumer (e.g. an industrial company or other large electricity consumer) can be a viable solution, the BWE has found. However, it is these more creative solutions that face the most headwind because of unsuitable legal conditions, Derouiche explained. To actually have an economic advantage from using their own electricity or supplying it to a nearby consumer, it is of crucial importance that certain levies and taxes are omitted. Under current legislation, however, this is not the case. “This makes the whole setup relatively unattractive,” Derouiche said.

Some of the wind power generated after 2021 in Ellhöft will be used on site to run an electrolyser and charge electric cars. However, Reinhard Christiansen also said that the current rules for own consumption of electricity were obstructive because of the many extra costs involved. “Here the government would have to seriously change course. But with Chancellor Merkel and energy minister (Peter) Altmaier at the helm that is unlikely to happen.”

Asked by Clean Energy Wire if any changes to existing legislation were planned to make sure that many renewable installations are capable of finding new profitable business models, the economy and energy ministry replied that the necessary legal framework is already in place, allowing for own consumption, storage and marketing renewable energy.

Cost-efficient direct marketing possible from a technical perspective

One of the more convenient solutions for the post-feed-in tariff era installations is signing up with a direct marketing company, which assumes responsibility for marketing the installation’s power at the electricity exchange and sometimes also offers facility maintenance and other extra services. The use of these service providers is already very common among renewable operators as selling their own power was made mandatory for larger than 100 kW installations in 2016, but few operators chose to market their power at the electricity exchange themselves.

Direct marketing companies have come up with various ways to earn money with renewable installations, with some buying up old renewable facilities, while others contracting them to create larger pools of generation and then selling the electricity to a larger customer.

Despite these offers and solutions by the companies, Peter Stratmann and Jan Sötebier at the Federal Network Agency are still worried about one “great unknown factor” – the millions of very small solar PV installations on private homes. Firstly, it is unlikely that all of these private households are going to actively figure out a new business model for their installation once the funding runs out. Secondly, there are concerns that direct marketing companies wouldn’t be able to sign up these very small, sometimes only 3-5 kWp, facilities at reasonable costs.

“These kinds of PV installations can earn up to 170 euros per year with the electricity they generate, provided that all output is fed into the grid. I have my doubts that handling them would be a feasible business model for a direct marketing company, after it has incurred costs by initiating and finalising the contract and getting the owner to have smart metering technology installed,” Stratmann told Clean Energy Wire.

“We sometimes hear that if companies managed to contract a large number of these very small installations and if everything would be standardised and automated with smart metering, they might have a chance to make a profit – if that is true we would be very happy,” Sötebier adds.

Running small installations at a profit indeed is a difficult task but nevertheless possible, said Hans-Günter Hogg of direct marketing company Beegy. "Technically speaking, the economics of smaller renewable energy sources are no different from that of bigger ones," Hogg said. He argued that this business model would depend on incorporating smart meters to be sucessful, but their roll-out in has been delayed in Germany due to safety concerns. "Marketing small installations at a profit can only work if procedures are automated as much as possible. The main obstacle we face here is regulation."

Lawmakers require that the power feed-in is metered every 15 minutes for accounting purposes, Hogg said. With current technology standards, this would ammount to costs of about 500 euros per year for installation and operation. "If you own a small solar panel with, say, 7.5 kwp, you just cannot generate that much income with it to pay for these administrative running costs." With smart meters as the standard technology, these costs could be cut by up to 90 percent, Hogg said. "We would like to demonstrate that we are capable of running a functioning business with small installations but are handcuffed by slow administrative proceedings."

If direct marketing options are not yet the solution for the many solar PV facilities, the government should think about alternatives, such as a non-funded feed-in scheme, the network agency's Stratmann and Sötebier suggested. Such an instrument would mean no change for the PV owner (apart from not being paid anymore), while their electricity would be marketed and transferred by the grid operators just like it is today.

But, according to Susanne Jung from the Solar Energy Support Association (SFV), this wouldn’t be enough. Since every solar PV operator has to cover costs, such as maintenance, insurance or metering, the electricity fed onto the grid would have to be remunerated with the wholesale electricity price (or at least five ct/kWh) and the renewable levy on self-consumed energy would have to be lifted, Jung wrote on the SFV website. “The easiest solution for operators of old PV facilities would then be to continue operating the system as a full feed-in system without any technical modifications,” she concluded.

The lights will stay on – but energy transition would be better off with renewable energy pioneers on board

The grid agency and the operators agree that neither the overall amount of renewable energy produced nor grid stability would be adversely affected by the possible loss in renewable capacity in the 2020s. “We do not expect any sudden, large-scale dismantling of old renewable plants with the abolition of feed-in funding. In addition, further new plants will be added,” Ove Struck, spokesperson at the distribution grid operator Schleswig-Holstein Netz AG, told Clean Energy Wire.

But Peter Stratmann at the network agency pointed to a different issue: “We want an efficient energy transition and all electricity consumers have paid a lot of money for the existing renewable facilities to be installed – it would be prudent for them to contribute to renewable power production for as long as possible”.