20 years on: German renewables pioneers face end of guaranteed payment

How much renewable capacity does Germany stand to lose once feed-in tariffs start running out?

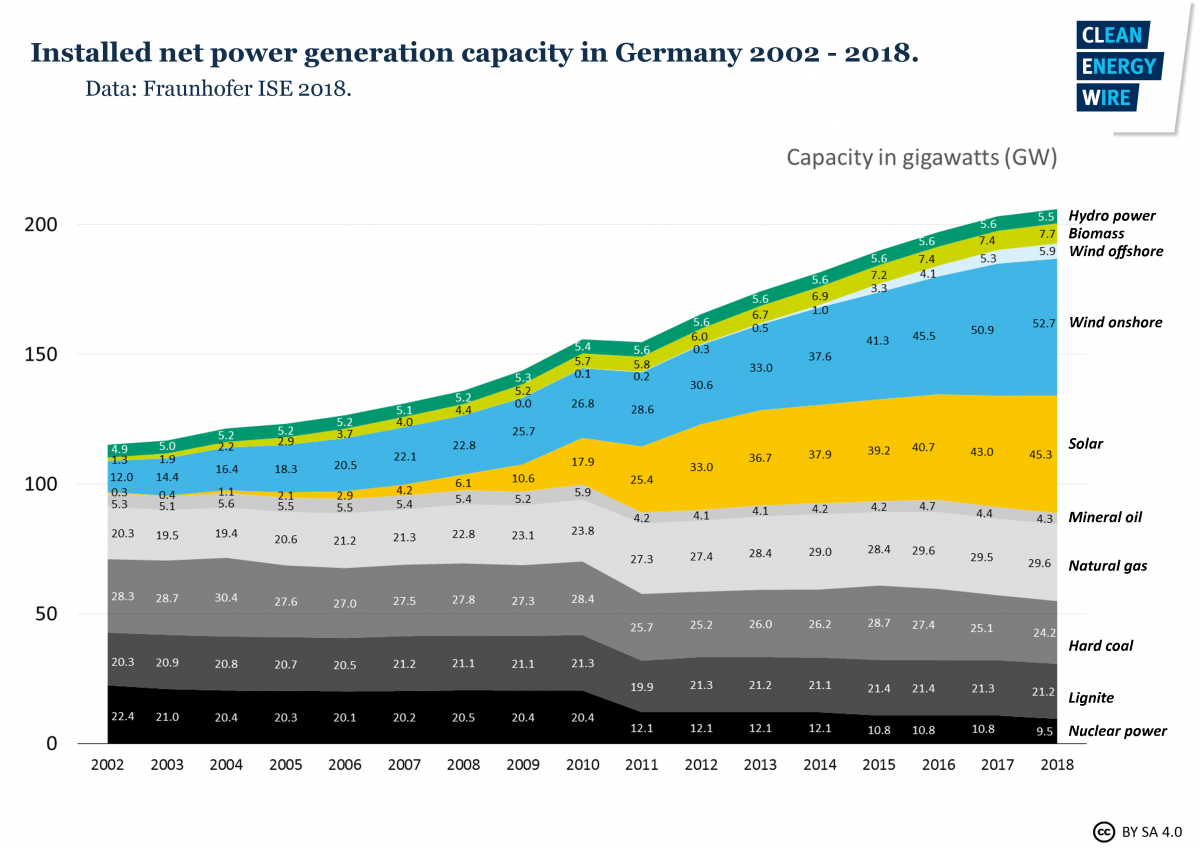

Germany’s renewable electricity capacity from solar panels, onshore wind turbines and biogas plants stood at 103 gigawatts (GW) in 2018, making up the bulk of the country's total renewable capacity (which also includes offshore wind, hydropower, etc) of 118 GW.

Renewable energy sources supplied 224.6 terrawatt-hours (TWh) or 34.9 percent of the country’s gross electricity production in 2018.

92.2 GWh (14.3%) came from onshore wind turbines.

46.2 GWh (7.2%) from solar panels.

45.1 GWh (7%) from biomass plants.

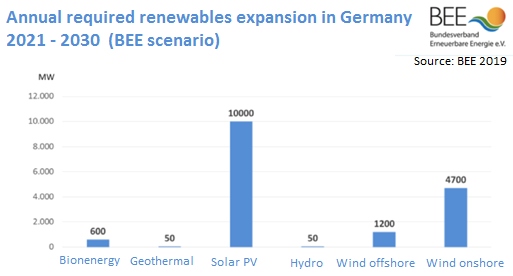

The government aims to have 65 percent of Germany’s electricity demand covered by renewable sources by 2030. To achieve this goal, the country has to increase its current renewable electricity capacity to anywhere between 215 and 237 GW, the German Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW) has calculated. Wind and solar power capacity therefore each have to grow by about 5 GW every year, according to the think tank Agora Energiewende*. Renewables lobby group BEE sets the total need for additional renewable capacity higher, at around 16.5 GW per year.

As of 2021, wind, solar power and biogas installations with several gigawatt of capacity will be over 20 years old. Therefore, these will stop receiving feed-in tariffs under the Renewable Energy Act (EEG), which were first introduced in the year 2000 and limited to a 20-year period. Throughout the 2020s, more and more of Germany's installed renewable power capacity will thus reach the end of the support period.

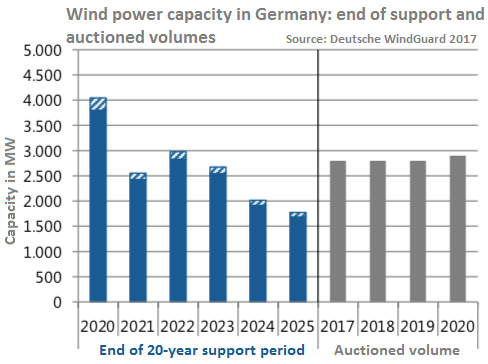

Feed-in tariffs will run out for 4 GW of onshore wind power alone on 1 January 2021, followed by another 2.3- 2.4 GW each year until 2025 (total of 16 GW), the industry organisation Deutsche Windguard has calculated. The country's wind energy capacity tripled from about 20 to nearly 60 GW between 2008 and 2018, figures published by the research institute Fraunhofer IEE show.

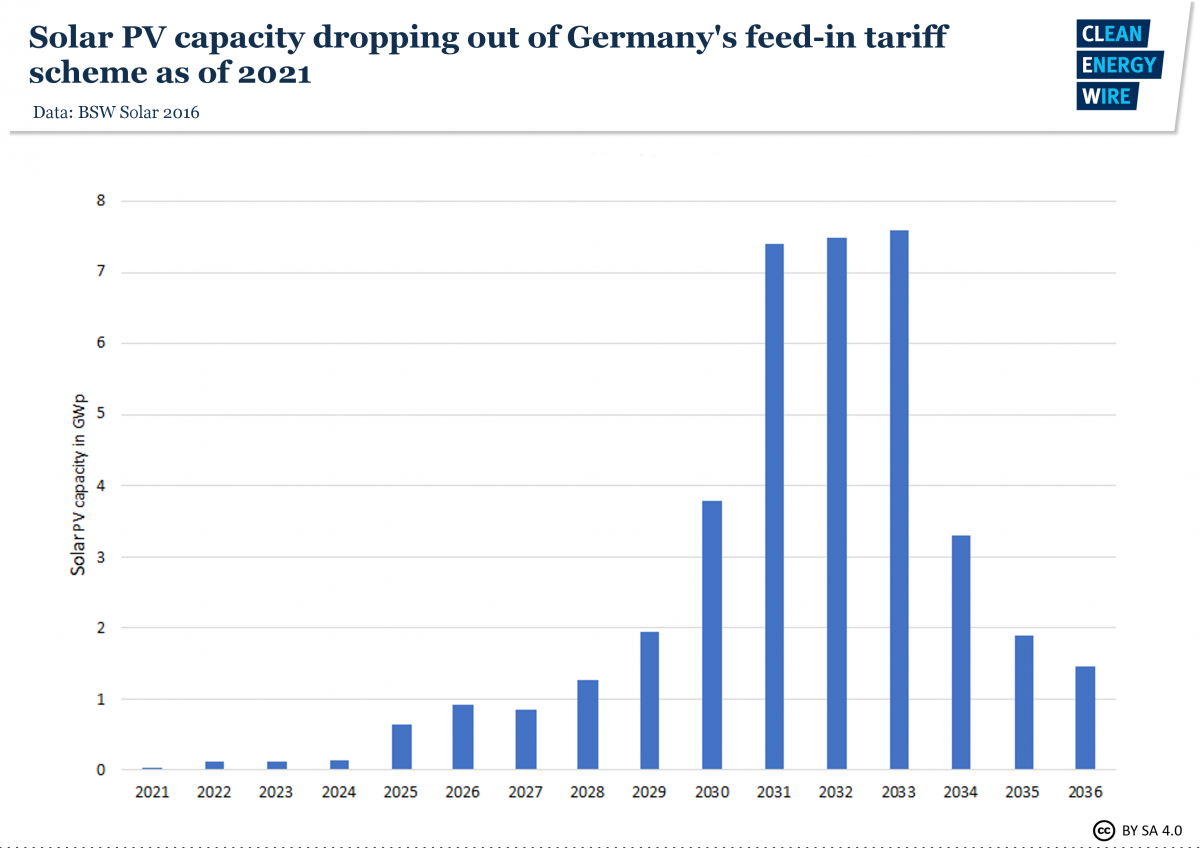

The bulk of Germany's solar power capacity in 2019 had been added between 2008 and 2013, according to the industry association BSW Solar, meaning that these installations will reach the end of their guaranteed remuneration between 2028 and 2033. As of 2028, this will make up over 1 GW per year, and rise to over 7 GW by 2031.

Management consultancy PwC says that by 2033, operators of more than a million solar arrays in Germany with an output of 24 terawatt-hours (TWh) will have lost their support payments.

Of the around 9,400 biogas plants currently in operation in Germany, roughly 1,000 could stop in 2021 when their remuneration runs out, the Fachverband Biogas estimates. Of the 6.6 GW in biomass facilities currently installed, about 5.1 GW will be available after the end of the funding period in 2025, and 2.3 GW will be left by 2030. The last plants eligible for EEG support would drop out of the support scheme in 2034.

It remains unclear how many renewable installations will stop feeding electricity into the grid due to not receiving guaranteed remuneration anymore, as this depends on the technology and the specific parameters of every individual plant, their technical condition and whether or not the operators find another business model for their installation.

What are the legal framework conditions for old renewable installations?

Although renewable installations that have received EEG feed-in tariffs for 20 years eventually lose this payment, they retain their legal status as renewable energy generators. This includes “connection priority” and “grid priority,” meaning grid operators are obliged to connect renewable installations to the network and give preference to feeding in renewable power over conventional electricity sources. Old renewable installations will also continue to receive compensation payments when their production is curbed by grid operators to stabilise the power network.

In return for retaining their beneficial status, renewable operations have to keep fulfilling obligations, such as installing certain metering technology and mandatory reporting to grid operators and the market register.

What are the business options for old renewable installations?

Renewable installations that have received lucrative feed-in tariffs for two decades may no longer be economically viable if the guaranteed remuneration ends and they are in need of repair, very small in size and output or simply no longer up to modern standards anymore. Some renewable operators will therefore choose to close down and dismantle their installations – wind farm owners are legally obliged to fully remove all turbines and their infrastructure once they end operation. As a rule, all renewable energy operators would have put aside funds for their facilities to be decommissioned. For onshore wind turbines, this was made mandatory in 2004. If their installations are still in good shape, however, renewable energy operators may stay in business. They have several different options to choose from:

- Repowering

Repowering means replacing old renewable installations with newer and generally more powerful models at the same site. Whether or not this is possible depends on the installation's exact location and the corresponding planning regulations, since new units might be bigger than their precursors or because local planning requirements may have changed. Repowering requires a new investment by the plant owner and, in the case of larger-scale wind or solar PV installations, either a power purchase agreement (PPA) with an electricity supplier or end consumer or the successful participation in a tender to receive a guaranteed feed-in tariff for a certain period of time.

- Direct marketing

Every renewable power supplier can sell their output at the electricity exchange. But for smaller wind parks, owners of small solar installations or operators of single biogas plants, this would not be feasible all by themselves. Instead, they can use the services of direct marketing companies. The direct marketer gets remote access to the plant, sells the renewable power at the exchange and transfers the earnings to the renewable power station owner according to the terms of their contract after subtracting a commission. This model is already well-established in Germany since many renewable installations (in particular those that became operational after 2016) are obliged to directly market their electricity at the exchange despite having a guaranteed feed-in tariff.

Direct marketing companies also offer other models, such as buying existing renewable installations or pooling the electricity production of their various customers. The power generated there is not sold on the exchange but transferred directly to another company or customer. For older and particularly for very small facilities (often meaning solar panels), it remains to be seen whether such installations are good enough business for direct marketing companies to take them on.

- Power purchase agreements (PPA)

Renewable energy operators can sell their electricity to one specific customer. These long-term contracts that are referred to as power purchase agreements (PPA) serve to finance the operation and/or construction of the plant. PPAs can take different forms, depending on whether the electricity is supplied physically via a grid connection to the buyer (e.g. a nearby company) or whether the purchase of the power (which is fed onto the public grid) is purely contractual because the buyer is an electricity retailer. In the case of direct line supply to a nearby consumer, the renewable energy generator becomes an electricity supply company (just like a coal power plant), which entails numerous legal and financial obligations (e.g. power tax, renewable levy payments). The buyer will be interested in a “guarantee of origin” (GO) for the renewable energy to be able to prove to its own customers that they are dealing with verified green energy. GO certificates can be purchased at Germany’s Register of Guarantees of Origin (Herkunftsnachweisregister, HKNR) at the Federal Environment Agency (UBA).

- Blockchain and community solutions

By integrating old renewable installations into district energy concepts, they can be used to supply power to homes or businesses nearby often in combination with heat pumps, e-car charging stations and battery storages. In the future, peer-to-peer power supply could become possible with blockchain solutions.

- Own consumption, storage and power-to-x

Once their 20 years of feed-in tariffs run out, renewable energy operators can also choose to use the electricity themselves, e.g. in an industrial or farming business or in their own household, depending on the type and size of the installation. The legal definition of “own consumption of electricity” in Germany is quite strict and important to operators because the power is (partially) exempt from the EEG-surcharge and therefore cheaper than paying for external power supply only if the power is produced by the same legal entity, is produced and consumed in close proximity and is not routed through the public power grid. If the electricity is produced in a wind or solar PV facility, using a form of storage, such as a battery, can increase the coverage of the power needs with the own installation - but again, this is subject to certain legal conditions in order for it to be a financially viable option.

The same applies when a renewable energy operator chooses to use the electricity in an electrolyser to create hydrogen or to operate a power-to-heat facility. Only in very specific constellations will this be financially attractive because of the many surcharges, fees and taxes that apply when power is generated, transmitted, stored and fed into the grid again.

What are the differences between wind, solar PV and biogas when it comes to operating them without feed-in tariffs?

- Onshore wind

The German Wind Energy Association BWE generally considers repowering to be the best option for old wind parks. However, according to a report published by the business association Deutsche Windguard, around 50 percent of today’s wind park sites will not be suitable for repowering because of changed land development plans, and another 20 to 30 percent will likely not be suitable because of new planning restrictions due to settlements or wildlife concerns.

If repowering is not an option, onshore wind parks are in the rather favourable situation that their larger electricity output (compared to small solar PV installations) is of greater interest to direct marketing companies - although this often does not apply to the very small pioneer wind parks built before the year 2000. If legal preconditions are met, own consumption, storage or direct power delivery to a nearby industry are also options for existing wind parks (see above). However, all of these business models are only viable if the wind turbines – after 20 years of service – are still in good working condition, generate reliable output and are not likely to need major repairs, which would make the whole venture a financial risk rather than a money earning opportunity. Before an older wind farm can enter into a contract with a direct marketing company or agrees a PPA with a consumer, it will therefore go through an assessment and verification process.

- Solar PV

The continued operation of ground-mounted solar PV installations older than 20 years will face challenges and opportunities similar to onshore wind parks (see above). Depending on their size and condition, they will be able to continue operation and sell their electricity. Repowering is also an option, in particular when the existing planning permissions are still valid or can easily be re-obtained. There are now cases of large new solar PV parks that will run entirely without state-supported feed-in payments. The same may apply to written-off but fully operational or repowered old PV installations, experts say.

The situation is somewhat different for the numerous very small (less than 10 kWp) rooftop PV facilities on private homes in Germany. Many of them will be the first to stop receiving feed-in payments in the early 2020s. Solar power researchers say that installing a battery to store and thereby consume more of the power generated on the roof could make the continued operation of the panels worthwhile for homeowners. If the additional investment in battery storage is not an option, homeowners could sell their electricity to or through a direct marketing company. However, the great unknown is whether the hundreds of thousands of small PV owners will be able to secure contracts for their very small amounts of electricity generated (link to Article).

- Biogas

In contrast to wind or solar power installations, old biogas plants have the option to enter into a new 10-year-phase of guaranteed feed-in payments by participating in an auction scheme set up by the government. Most biogas plants are too expensive to operate with no other income than the electricity price they can achieve at the exchange because unlike solar PV and wind turbines, they have to be supplied with substrate (biomass) and require constant supervision. So far, biomass tenders have been undersubscribed.