German onshore wind power – output, business and perspectives

Quick facts

(Figures for 2024; Sources: BWE, AGEB, UBA, BNetzA)

Number of turbines installed: 28,766

Total installed capacity: 63.4 GW

Additions in 2024: 3.2 GW gross / 2.5 GW net

Projected expansion: 115 GW (2030)

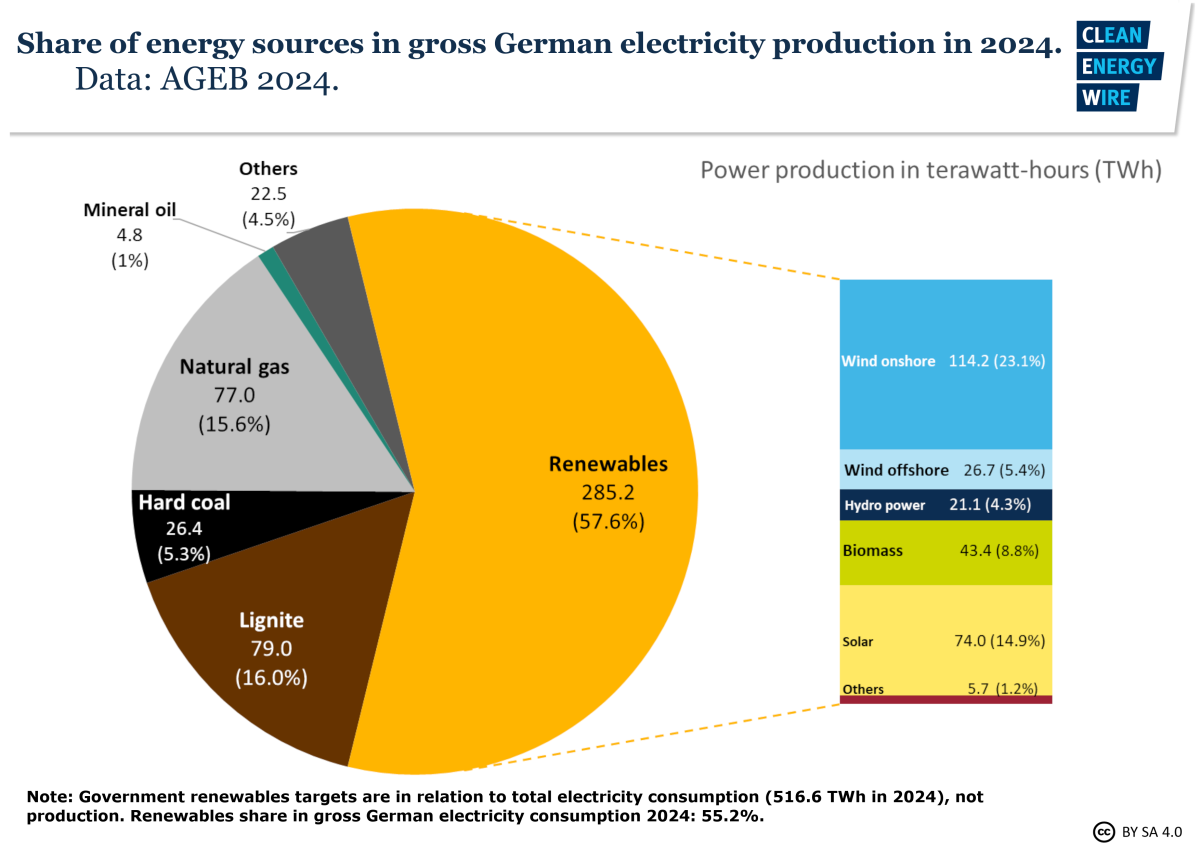

Share in gross power production: 23.1%

Output: 114 TWh

Jobs (onshore & offshore): ≈ 130,000 (2021 est.)

Average auctioned support level: 7.15 ct/kWh (November 2024)

Overview

As an early adopter of onshore wind power, Germany has developed into a leading market and technology incubator since the early 2000s. Thanks to its trademark Renewable Energy Act (EEG), guaranteed state support helped eager investors to bring the technology to scale and made the country a frontrunner in expanding the share of wind power in its electricity generation mix. With more than 28,000 turbines and a cumulative capacity of 63 gigawatts (GW) in operation across the country, Germany boasted the largest installed onshore wind fleet in Europe and the third largest globally in 2024.

The annual rate of expansion has varied greatly throughout the past years. With a net expansion of about 5.3 GW, 2017 showed the strongest growth in capacity of any year so far. Following a change in the support regime in the year after, from fixed guaranteed remuneration rates to a system in which the required support is determined through auctions, expansion dropped to less than one GW in 2019, the lowest level in two decades.

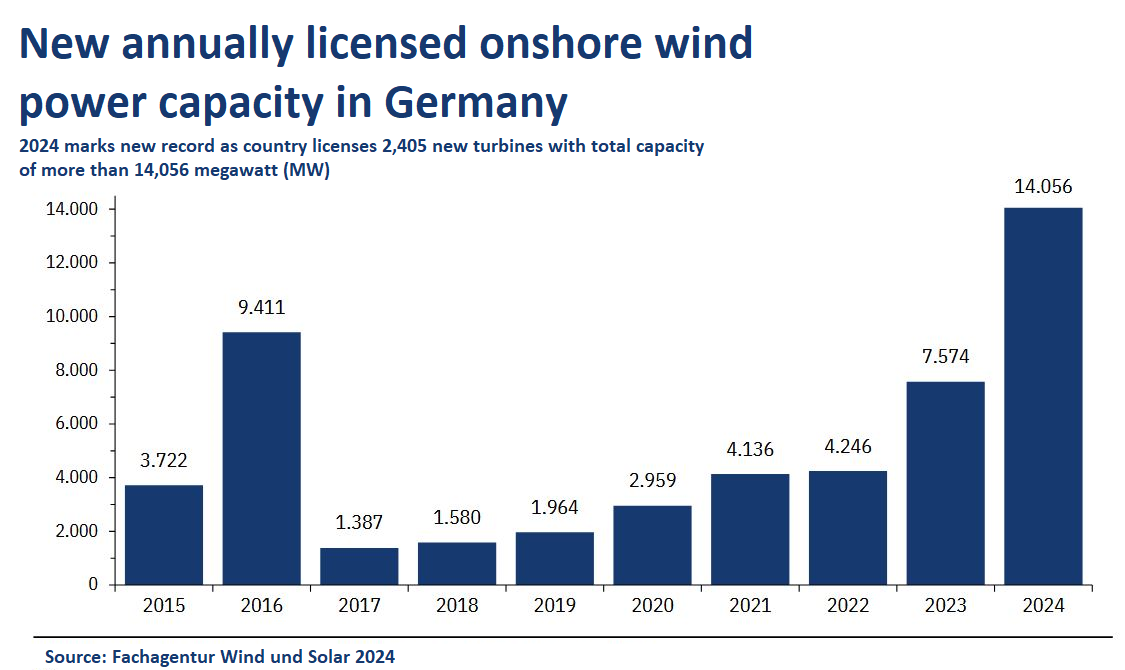

After a string of regulatory changes in the following years, particularly regarding licensing and land use, gross expansion climbed back to 3.5 GW in 2023. According to the German Wind Energy Association (BWE), 2024 then marked “an absolute record year” as 2,405 new turbines with a total capacity of over 14 GW were licensed. Another 1,890 turbines, with a capacity of nearly 11 GW, were awarded in auctions. “Both are never-seen-before figures and will lead to a significant increase in expansion over the coming years,” the industry group said.

While the mood in the industry has recovered since the dip in 2019, companies remain worried about long-term developments in the sector, illustrated by a state support payment worth more than seven billion euros to wind turbine producer Siemens Energy in 2023.

The industry hopes that wind power’s key role in Germany’s and the EU’s push for greater energy independence following Russia's invasion of Ukraine will allow the sector to gain greater planning security and embark on a steady growth path in the years to come.

The new workhorse of Germany's electricity system

Irrespective of the many challenges faced by turbine construction in recent years, onshore wind power has been Germany’s single most important electricity source since 2019. In 2024, onshore turbines contributed 23 percent to gross electricity generation with an output of about 114 terawatt hours (TWh). The overall share of renewable power reached a record high of 57.6 percent. During the particularly windy year 2020, power consumption stayed low for many months due to the coronavirus pandemic, making it the first time in the country's history when renewables overtook fossil fuels in total electricity production.

During the three years of chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition government, between the end of 2021 and the end of 2024, the country’s onshore wind capacity grew by 14 percent. But the coalition’s collapse in November 2024 also had implications for the wind power sector, the BWE said. A new power market design continued to be a priority for the industry to establish a more reliable long-term investment perspective, as well as viable policy proposals for more storage capacity, energy sharing and direct supply to industrial customers, the lobby group argued.

Likewise, a new government would have to work on improving the cyber security of wind farms, the BWE added. In its 2024 report, the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) also noted that targeted attacks on the satellite connection of some turbines in Germany foreshadowed the role renewable energy installations would play in the country’s future security considerations.

However, while power output has generally grown in parallel with installed capacity over the past few years, particularly weak-wind years, such as 2021, have dented the output curve and served as a reminder of the technology’s fluctuating production profile. Wind power generation generally peaks during the winter months, partly balancing out lower power input by solar installations. Onshore turbines delivered nearly 21 billion kWh of power in February 2022 alone.

As an intermittent energy source, however, wind turbines sometimes have a very high output, while in other periods only a fraction of the installed capacity is feeding into the grid. In the latter case, the German word ‘Dunkelflaute’ (dark doldrums) has found its way into the international debate to describe a situation that occurs for about two weeks each year, in which little wind and sunshine severely cut renewable power production and the vast majority of Germany’s power demand has to be covered by conventional power plants.

The government has been working on a scheme to build a fleet of new hydrogen-ready gas power plants that are supposed to replace coal-fired power plants whenever additional generation capacity must be deployed. However, the adoption of the Power Plant Security Act, which was meant to prepare auctions for the plants that are often expected to only run for a relatively short time every year, has been derailed by the Scholz coalition’s collapse. It is now likely to be introduced by the next government.

Reforms in licensing and land utilisation bolster buildout

After entering office in late 2021, Scholz’s coalition government set the goal of reaching a total installed capacity of 115 GW by 2030. While ambitious, this is still “nearly” in line with the Paris Climate Agreement’s target of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, according to an analysis by the New Climate Institute. To achieve it, Germany would have to ramp up annual expansion figures to nearly 13 GW in the next few years, more than four times the 2024 figure. While the average capacity of installations continues to grow steadily, marking a ten percent increase in 2023 alone, Scholz said the country would still have to build up to five new turbines per day to meet the target, a rate that was already achieved in 2017.

However, despite the recent success in boosting licenses and awarded auction volumes, researchers are sceptical whether Germany can reach its short-term expansion targets. With 2.5 GW added in 2024, net expansion remained modest due to the decommissioning of old turbines. The country’s roughly 63 GW capacity installed in 2024 falls short of the 69 GW intermediary target set by the EEG for that year. The slow pace of implementation and construction, combined with low turnout in previous auctions, raises doubts about whether the 84 GW of installed capacity target for 2026 can be met.

Together with insufficient construction space, regulation has been a major obstacle for onshore wind expansion. According to a 2023 analysis by industry lobby group BWE, the average duration from planning to licensing of a wind farm was four to five years. Economy minister Robert Habeck in late 2022 insisted that the individual efforts of the federal states are entirely to blame for the slow expansion. Strict state regulations, like Bavaria’s 10H-rule requiring a minimum distance between a wind farm residential buildings of at least ten times a turbine’s height, have undermined the energy transition’s progress.

The 2022 Onshore Wind Power Act introduced standardised assessment procedures, for example regarding species conservation, across all states to speed up licensing procedures. It also stipulated that larger states must contribute two percent of their territory as possible locations by 2032, while densely populated city states are required to designate 0.5 percent. The space for more turbines is “clearly available,” according to a study by research institute Fraunhofer IEE, while an analysis by environmental think tank KNE found that only a fraction of the two percent target area will ultimately be needed for construction.

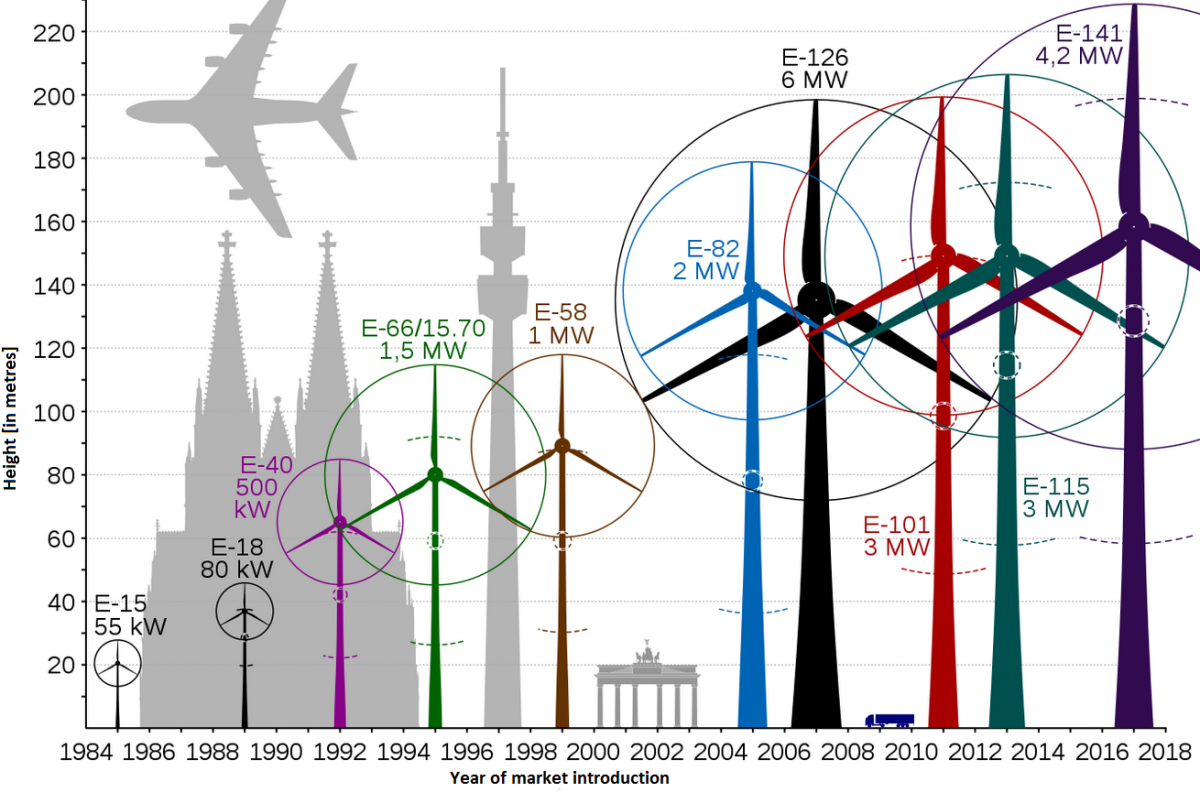

Growing turbine size changes calculations

New turbines continue to grow in size and deliver more output: installations added in 2024 had an average capacity of over 5.1 MW, a hub height of 143 metres and a rotor diameter of 146 metres – an increase of 40 percent over the past decade. New installations can thus produce more power and greatly increase output at a given location if old turbines are replaced in so-called repowering procedures.

A single modern onshore turbine produces enough electricity on average to supply about 6,000 households. Replacing older models that in some cases have been in operation for more than 20 years through repowering is therefore seen as one of the most promising ways to quickly ramp up wind power’s share.

Greater energy yields and more operating hours per turbine, meanwhile, have compensated for a planned decline in support and made it possible to build on previously unattractive locations. But even though greater efficiency made inland regions further south with weaker winds more attractive to investors, expansion levels there still lag far behind those in the north.

Uneven turbine distribution causing technical and political problems

At the beginning of 2022, around 0.85 percent of Germany’s land area had already been designated for wind farms, with figures varying widely between states. In 2023, the government said it was optimistic that the 16 federal states and their subordinate administrations had generally begun to embrace new turbines on their territory as an economic advantage.

The surge in newly issued licenses for wind farms has already begun to influence the value of designated construction areas, for which lease prices have increased fast in recent years, eating up a growing share of the turbines’ annual revenue – particularly regarding construction sites on publicly owned land. Industry group BWE therefore has called for a maximum limit on prices for land use to prevent rent costs from becoming a bottleneck in the technology’s further expansion.

A 2024 analysis of Lower Saxony, Germany’s leading wind power state, found that new wind farms benefit the local economy and municipal budgets. Beyond the immediate economic boost from constructing and operating new wind farms, indirect effects, including newly created jobs or the availability of cheap renewable power for the manufacturing industry, could add to the turbines’ benefits for locals.

However, the distribution of wind turbines continued to be heavily skewed in 2024. While most of the existing capacity is installed in the windier northern and eastern regions, the western state of North Rhine-Westphalia started to catch up in the past year only, while the southern states of Bavaria and Baden-Wurttemberg continued to linger well below their potential for installing new turbines. “There finally must be a trend change in southern Germany. This is also required for grid stability,” the BWE said.

The uneven distribution of wind turbines is increasingly putting a strain on the country’s energy transition, both from a technical and a political perspective. Due to the slower expansion of renewables in southern Germany - and compounded by insufficient preparation for the closure of the country’s last nuclear plants in 2023 in regional energy planning coupled with the loss of Russian pipeline gas - renewable electricity production in the region often does not meet demand. At the same time, balancing the grid in times of excessive wind power influx in the north is becoming increasingly difficult as the necessary large power transmission lines have been delayed for years.

In 2023, the equivalent of about four percent of the country’s renewable power output had to be curtailed due to insufficient transmission capacity at times when local electricity production outweighed demand. In these cases, grid operators need to intervene with costly re-dispatch measures to avoid grid disturbances. An assessment procedure by the EU to adapt power pricing zones to a changing energy system could endorse splitting the country into a northern and a southern zone, which would therefore likely result in much higher prices in the south. This measure has been fiercely rejected by industry groups and lawmakers from southern Germany, who argue that grid expansion will eventually be brought to scale and that the different price zones could undermine national unity on the issue.

Citizens generally welcome onshore wind expansion

Surveys suggest that people in Germany remain overwhelmingly in favour of further onshore wind expansion. Generally speaking, the acceptance of more renewable power infrastructure has grown with the European energy crisis and Russia’s war on Ukraine, since more wind and solar power are believed to increase the country’s energy sovereignty. A survey published in early 2024 found that more 81 percent consider the expansion to be important or very important. The survey also compared attitudes in urban and rural areas, where most turbines are built, and found that there was very little difference between them.

A different survey published in summer 2024 compared attitudes between eastern and western Germany. It found that support was markedly stronger in the west – but also that well over half of respondents in the east endorsed further expansion. In yet another survey, carried out in the eastern state of Saxony and published in mid-2024, more than two-thirds of respondents said they agreed with the statement that Saxony needed a cross-party consensus on how to successfully switch from fossil to renewable energies. Only 18 percent did not agree.

Lawsuits brought by citizen campaigners and by environmental groups that used to be widespread throughout the past years to a large degree have subsided, not least due to regulatory changes that set higher hurdles for legal objections. According to reporting from national broadcaster SWR from early 2025, most of 440,000 objections to wind power in German state Baden-Wurttemberg handed over to authorities in 2024 stemmed from a core protest group of which each member sent 65 complaints on average.However, anti-wind power sentiments continue to linger in parts of society and the technology’s impact on the landscape repeatedly causes it to be singled out as a symbol of broader energy transition debates.

From layoffs to skilled labour shortage: wind makes for volatile job machine

Wind power has been the most important creator of jobs in the renewable energy sector in recent years. Out of about 344,000 jobs linked to the renewable energy sector in Germany in 2021, roughly 130,000 were in the (onshore and offshore) wind power industry, Germany’s Federal Environment Agency (UBA) said in a 2022 analysis.

However, achieving climate neutrality before mid-century will require even more labour, according to the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce (DIHK). An analysis by DIHK found that an additional 350,000 skilled workers would be needed in Germany to plan, build and operate renewable power and hydrogen production facilities by 2030. Reaching these numbers could be a considerable challenge: Another analysis commissioned by the Bertelsmann Foundation found that traditional craftsmen often lack the skills needed in the renewable energy industries. Targeted training for traditional craftsmen would thus be needed to provide them with the expertise required in the solar or wind power industries.

However, despite projections showing a huge uptick in the number of wind turbines being installed in Germany and elsewhere in Europe in the coming years, a job in the wind power industry so far does not necessarily mean secure employment. Industry association BWE estimated that up to 40,000 jobs might have been lost in the German wind power sector since 2017 due to the slow buildout.

The closure of Germany’s last wind turbine rotor production facility, announced by operator Nordex in mid-2022, led to further concerns that the country risks losing its domestic manufacturing capacity. The closure of a turbine plant by Danish manufacturer Vestas in a former east German coal region raised additional doubts whether the renewable power industry is capable of replacing jobs lost in the fossil sector. However, an annual survey conducted since 2015 by labour union IG Metall among works council members about business expectations showed that the mood within the industry has brightened significantly in recent years – with more than two-thirds in mid-2024 saying they expected a positive overall market development.

Yet, IG Metall warned that capacities for producing new wind turbines in Germany and the EU are insufficient to cover the rapidly growing demand. If domestic turbine production capacities are not increased significantly, Europe runs the risk of steering itself into novel energy supply dependencies, it argued. The union said greater investments are necessary to keep production capacity in lockstep with surging demand, a measure that could combine climate action with industrial policy for the future that provides secure jobs in the long run.

From guaranteed support to controlled competition

Initially, the success of Germany’s wind industry was made possible through state support payments laid out in the country’s Renewable Energy Act (EEG) in the year 2000. It granted operators guaranteed remuneration for electricity fed into the grid at fixed rates for a period of 20 years.

In 2017, the support scheme underwent a fundamental shift from politically determined support rates to an auction system in which bidders demanding the lowest guaranteed remuneration for operating their turbines would be awarded. The switch from predetermined feed-in tariffs to rate-setting in auctions was aimed at strengthening market principles and competition in the sector.

Besides implementing changes to the funding mechanism, the government also capped the total supported volume and in 2019, only installations that won an auction were eligible to receive support for the first time. However, while the introduction of the auction system was followed by falling support levels, onshore wind tenders in the following years were mostly undersubscribed and ended up attracting fewer applications than expected. By mid-2024, auctions were again oversubscribed – but only after the responsible Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) cut the auctioned volume by about one quarter.

Disrupted supply chains, rising material and energy costs as well as higher interest rates as a result of the combined economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine all had worsened the investment climate throughout the past years, according to wind power lobby group BWE. It therefore had called for increasing support rates in auctions to compensate for the loss in investor confidence. The BNetzA ultimately raised the maximum support rates in auctions from an average of 5.87 cents per kilowatt hour in late 2022 to 7.15 ct/kWh as of late 2024.

The first turbines reached the end of their 20-year guaranteed support period in 2021. Observers warned that this could lead to a decrease in installed capacity if low expansion levels persist. The BWE said it was difficult to gauge when individual windmills will be decommissioned, adding that it hoped business models like power purchase agreements (PPAs) could cushion the effects of expiring guaranteed support.

Cheap Chinese competition prompts industry to call for more assistance

Early on, Germany’s turbine manufacturers and wind power project developers started to also operate in markets abroad. Between 2010 and 2018, about 60 percent of the manufacturers' total revenue was generated outside their home country, figures by VDMA Power Systems showed. But small profit margins and stiff competition in recent years have made it harder for companies to keep up with international competitors.

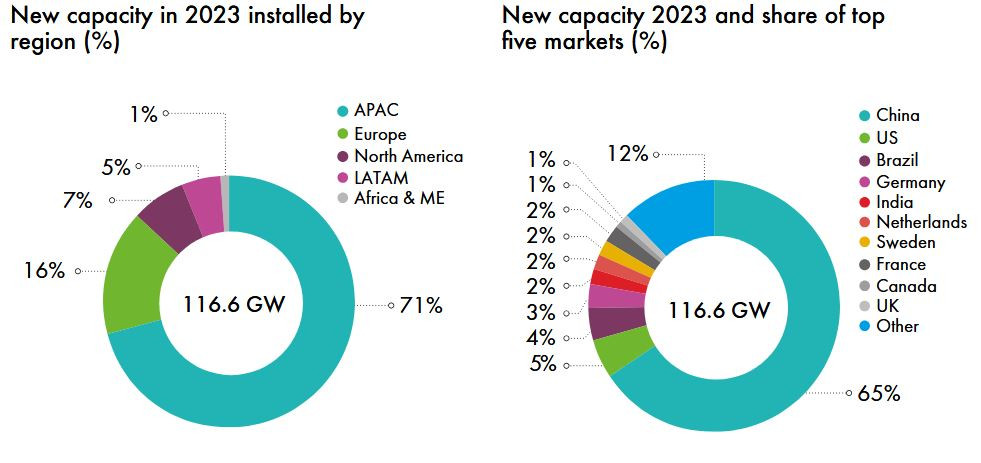

In a global ranking compiled by Bloomberg New Energy Finance in 2024, only two German-owned companies (Nordex and Siemens Gamesa) remained among the top ten wind turbine producers globally. Similarly, while Germany accounted for about seven percent of all installed onshore wind power capacity worldwide, it only contributed three percent to the capacity added in 2021, the Global Wind Energy Council's (GWEC) 2022 report showed.

Pointing at the fate of Germany’s solar PV sector, the country’s wind power industry has become more vocal in recent years in warning against a takeover of this key technology field by Chinese competitors, who already dominate in global commissioning rankings. In 2024, German producers were alarmed by the first German offshore wind farm project announcing the use of Chinese turbines. Labour union and wind industry company representatives said China is using “unfair” industry subsidies to promote its own wind turbine manufacturers that prompt operators in Europe to make shortsighted decisions based on low prices. These decisions would have long-term negative consequences regarding industrial prowess, economic stability and energy security, they argued.

In late 2024, the German government and the European wind power industry agreed on a set of measures to tackle challenges regarding the sector’s competitiveness, continued investments and infrastructure security against digital or physical attacks. Crucially, this would also include assessing market distortion and public support options. However, the coalition’s collapse is likely to stall fast progress on these issues.

Together with a range of other climate-friendly technologies, wind power remains among the most promising fields for German companies to thrive in the coming years, the Federation of German Industries (BDI) said in a report on the industry’s view of the country’s energy transition.

In a bid to regain a stronger position in the scramble for global market shares, Germany’s wind industry seeks to continue innovating the technology and retain a competitive edge despite its higher production costs. This includes efforts to make the construction and disposal of wind turbines more sustainable as well as to enhance the performance and versatility of installations. In 2024, construction of the world's tallest wind turbine started in a coal mining region in eastern Germany. The planned height of the turbine is 364 metres including blades, and the operators say that stronger winds at greater altitudes could boost the installation’s power output by 40 percent compared to smaller models.

Other developments include the coupling of electrolysers with wind turbines for producing green hydrogen on-site together with cooperation partners in Denmark, a procedure that could cut production costs of the valuable synthetic fuel if trial runs prove successful.