Unravelling the climate footprint of U.S. liquefied natural gas

The flare opposite Sue and Jim Franklin’s front porch was burning almost constantly, turning night into day. The couple recounts that before the intense drilling activity began in 2014, they could step outside into the complete darkness of the West Texas desert and gaze at the stars. Three years later oil and gas companies had drilled so many wells near their home that “you didn’t have a night,” says Sue.

Within a few years, the no-man’s land around their little town of Verhalen was completely transformed and the fumes, noise and lights destroyed the life they had, say the two owners of a rock shop that sells minerals and jewellery tourists and locals in the area. When an oil company approached their attorney asking how much they would want for their land, Sue and Jim made a deal and moved away in 2019. “We had to go. It makes you angry that you had to do that,” says Sue. “When Jim bought the place, he bought it to retire. To die on.”

At the time of the research for this story in February 2020, a huge drilling rig had been set up where their house stood just months earlier. Up and down the road, construction of new pipelines was taking place, flares burned at existing oil and gas wells and there was a constant flow of passing trucks hauling oil, extraction equipment, or water, chemicals and sand needed for hydraulic fracturing. The coronavirus had not yet fully hit the United States and new wells were still being drilled throughout the region.

The couple’s former home is situated in the middle of what is known as the Permian Basin, the world’s biggest oil- and the United States’ second biggest gas-producing region. The flares that could be seen from their front porch are only part of the impact the industry in this area is having on climate change. Together with methane emissions, they challenge the promotion of natural gas as a low-carbon alternative to coal, which the U.S. is pursuing around the globe, including in the EU.

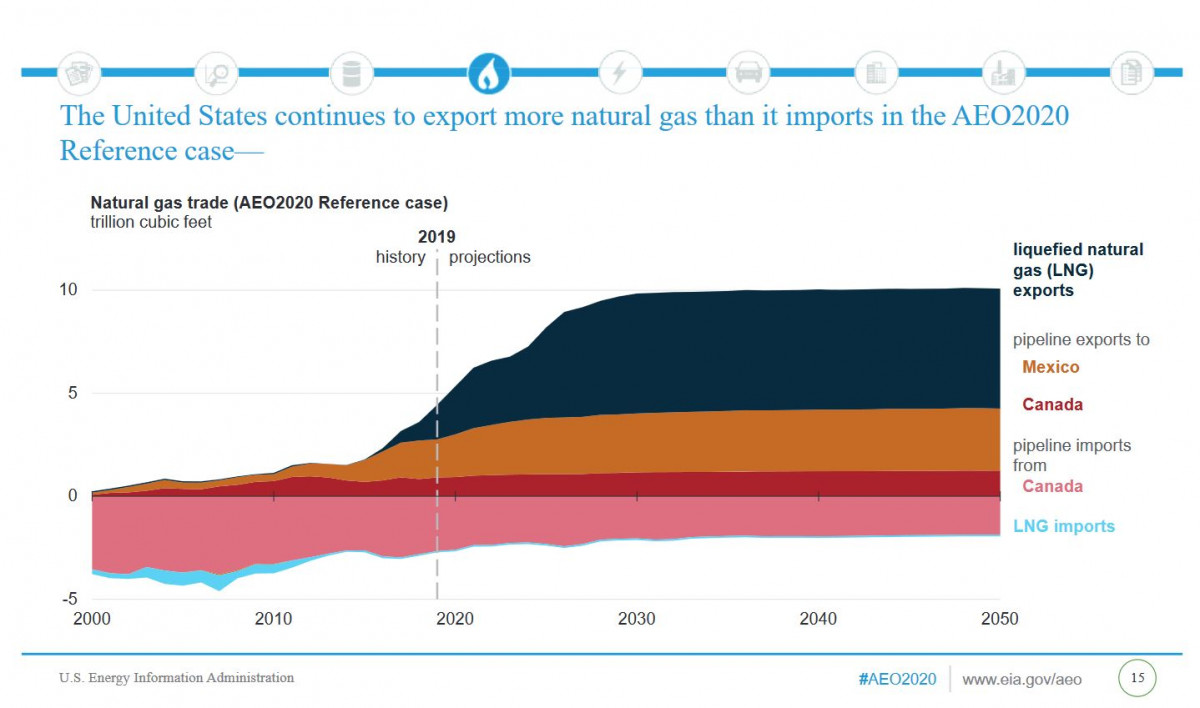

The United States has grown to become the world’s biggest oil and gas producer thanks to a boom made possible over the last decade by new extraction techniques, notably horizontal drilling and the controversial hydraulic fracturing – also known as fracking. While the rapid increase of extraction started under former President Barack Obama, the current government of Donald Trump has put great emphasis on sending the fuel abroad, so far mostly to Asia and Europe. The country has been a net exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) since 2016. It delivers to more than 30 countries and is set to overtake Australia and Qatar to become the world’s biggest supplier by the mid-2020s.

Much of that gas will come from the Permian Basin, a region in Texas and New Mexico with prolific growth and closer than many other fields to the bulk of the country’s export terminals along the Gulf of Mexico. “We’re unlocking the full oil and gas potential of the Permian Basin in Texas and New Mexico and sending it right here to you. […] And you’re shipping it all over,” Trump told workers at an LNG export facility in the neighbouring state Louisiana last year.

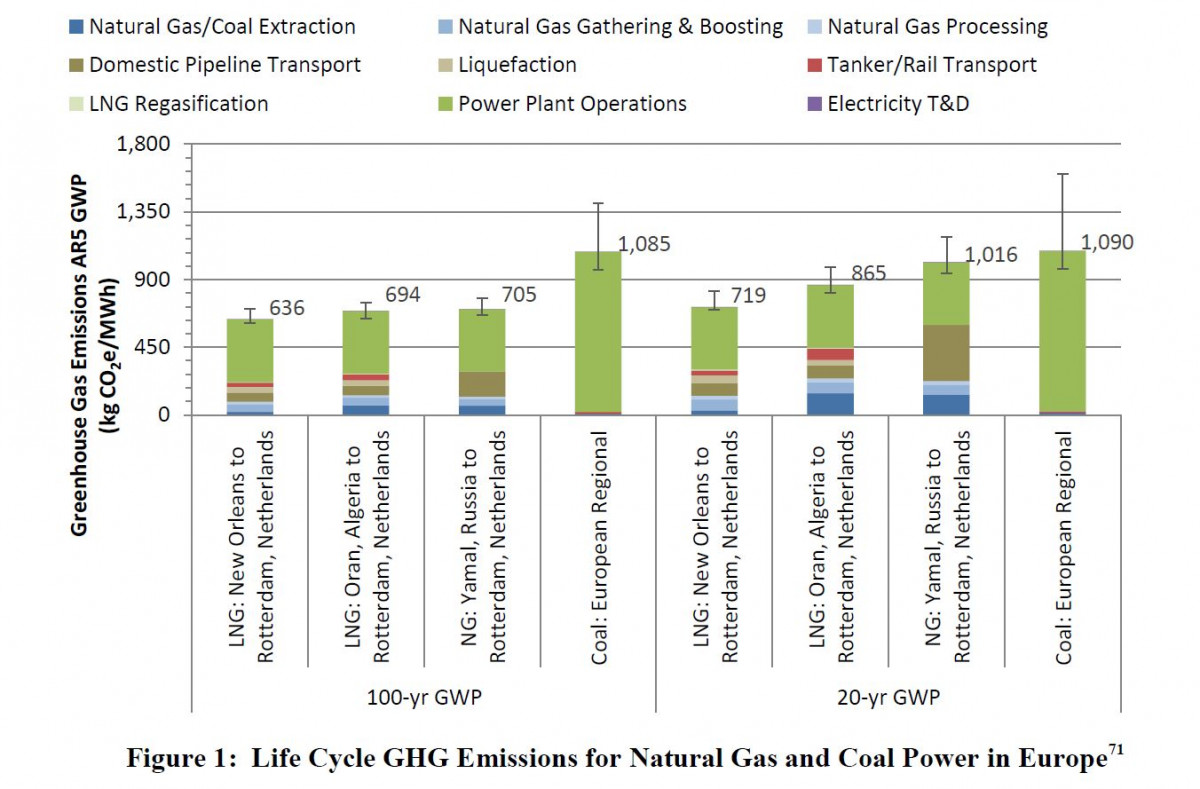

To European partners, the U.S. administration has offered gas not only as a way to lessen dependence on Russian supply, but also to help phase out coal, because burning it emits about 50 percent less CO₂ than the dirtiest coal – lignite. “As countries are trying to lower their emissions, for example under the Paris [climate] accord, natural gas has to play a significant role in it,” Shawn Bennett, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Oil and Natural Gas at the U.S. energy department, told Clean Energy Wire. [Also read the article Coronavirus crisis highlights risks of U.S.-European LNG deals diplomacy].

Highest methane emissions ever measured from a major U.S. oil and gas basin

There is a catch: when it comes to the Permian, high greenhouse gas emissions from the oil and gas industry could mean that the climate benefits of U.S. natural gas over European domestic coal are all but eliminated. Two recent studies show that the flaring, venting and leakage of natural gas are a much bigger issue in the Permian than elsewhere in the country.

First ground and aerial measurements from the ongoing year-long project PermianMAP by advocacy group Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and satellite observations show the highest methane emissions ever measured from a major U.S. oil and gas basin. At 3.7 percent of the gross gas extracted, it is 60 percent higher than the national average in other research, and about three times the rate reported in the Environmental Protection Agency’s nationwide statistics. The amount of methane escaping from Permian oil and gas operations nearly triples the 20-year climate impact of burning the gas they’re producing, says EDF – one of the country’s most prominent voices on the issue. The researchers see a bright side in their results because they see an opportunity to reduce methane emissions in this rapidly growing oil- and gas–producing region through better design, effective management, regulation, and infrastructure development.

As a greenhouse gas, methane (CH4) – the main component of natural gas – is more potent than CO₂, especially when looking at shorter time horizons. Reducing its emissions can effectively reduce the near-term rate of warming.

Tackling methane for short-term climate action

By the time it is used in Europe, U.S. LNG has left behind a long trail of climate-harmful emissions. Total greenhouse gas emissions from extraction, processing, pipeline transport, liquefaction, ocean transport and regasification can make up 50 percent and more of the climate footprint of power generated in a European LNG-fed gas plant. The rest comes from burning the gas.

Not all of these emissions are carbon dioxide. Alongside it is methane (CH4) – the main component of natural gas. It is the second major contributor to global warming originating from human activity.

As a greenhouse gas, it is more than 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20-year horizon. However, its effect is comparably short-lived. Most of it is removed from the atmosphere through chemical reactions during the first two decades, while CO₂ stays much longer and has to be absorbed by land or ocean sinks. Thus, reducing CH4 emissions can effectively reduce the near-term rate of warming. [view this thread by climate scientist Zeke Hausfather for an explanation]

Since the mid-2000s, methane levels in the atmosphere have been rising rapidly – with the latest jump in 2019 – and there has been some debate on whether the cause is natural or human activity. Recent studies suggest that the oil and gas industry could play an important part. In 2019, researchers from Cornell University concluded that “the commercialisation of shale gas and oil in the 21st century has dramatically increased global methane emissions.” In a 2020 study from the University of Rochester, researchers found that scientists have been vastly underestimating the amount of methane humans are emitting into the atmosphere via fossil fuels.

The International Energy Agency (iea) says the oil and gas sector is responsible for about a fifth of global methane emissions and reducing these is a relatively cheap way of tackling climate change. One-third of methane emissions from oil and gas operations could even be avoided at no net cost, also at current low gas prices, it says. “The message is clear: even with an over-supplied gas market, reducing methane emissions from oil and gas operations is amongst the lowest of low-hanging fruit for mitigating climate change.”

Scientists have said in different studies that a leakage rate of about 3 to 4 percent should not be exceeded to ensure that burning natural gas has an overall climate benefit over domestic coal in U.S. electricity generation. Add to that emissions from liquefaction and ocean transport to Europe, and the allowed leakage rate is slightly less. It is noteworthy that the Permian study’s 3.7 percent rate includes methane emissions from oil production. Differentiating between emissions from oil and gas production is especially difficult in this region. Due to the massive and lucrative oil development, gas produced by oil wells – which is called “associated gas” and is often seen as a mere by-product – makes up more than half of total natural gas production in the region.

Thus, as a “good chunk” of the gas headed for one of the LNG export terminals along the Gulf coast comes from the Permian Basin, what happens here is “extremely important”, Colin Leyden, an Austin-based oil and gas industry expert at EDF, told Clean Energy Wire. “Associated gas in the U.S. and in Texas specifically is not a niche market. It’s a big piece of the total gas produced.”

Europe turns an eye to methane

The European Union has decided to tackle the issue. “Methane emissions harm the credibility of gas today as a transition fuel towards a decarbonised energy system,” the European Commission has said. As part of its Green Deal, the Commission aims to make the gas sector increasingly climate-friendly. It sees reducing methane emissions as “a quick and cheap contribution to keep the global temperature increase below 2°C” and a valuable help in reducing the bloc’s overall greenhouse gas emissions by 50-55 percent by 2030, a target currently under discussion in the EU.

The Commission is working on a methane emissions strategy, covering measurement, reporting and verification across oil, gas and coal sectors and supply chains and possibly looking at other sectors too (agriculture, waste). The strategy is expected to be finalised by May or June of this year and the Commission said it would introduce concrete legislation in 2021.

EDF’s Leyden welcomes the debate in Europe. “From a market perspective, large consumers have a role to play in making sure that they account for all of the climate implications all the way up the value chain if they are going to use LNG or natural gas as part of a transition programme,” he told Clean Energy Wire.

It is as of yet unclear what the methane strategy would mean exactly. However, strict standards would force natural gas producing regions across the globe to seriously tackle the issue – if they want to continue to supply the EU.

Lack of data are main pitfall in comparing climate footprint from different regions

However, due to a lack of measurements, no one knows the true scale of methane emissions from oil and gas production, which makes comparing gas from different regions extremely difficult, if not impossible.

“People are throwing around whatever they want in terms of numbers and we need to bring order to this chaos,” said Nikos Tsafos, senior fellow at the D.C.-based policy research organisation Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). “I know people in the U.S. who are convinced that once you do the numbers right the U.S. will look great,” said Tsafos. “And there are those who think the U.S. would be totally prohibited from reaching European markets.”

More measurements necessary to find out true scale of methane emissions

The problem is that no one knows the true scale of methane emissions from oil and gas production.

Levels reported to the United Nations are largely based on calculations, not measurements. A common approach in the national greenhouse inventories annually prepared by each country is to use emission factors for individual activities as well as measurements – if available – to scale up to countrywide emission inventories.

“A company would say ‘we have x-number of pneumatic valves, we flared y-amount of gas. These are how many tanks we have’ and then they do an emission factor calculation,” explains Colin Leyden, oil and gas industry expert at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). “It is not a very accurate way of estimating emissions.”

Over recent years, there have been numerous studies using measurements and calculations to varying degrees to assess methane emissions in different producing regions in the United States. In 2018, EDF led a group of researchers on a report that synthesised several studies. It said supply chain methane emissions were about 60 percent higher than the EPA’s inventory estimate. The scientists said the large divergence was due to the EPA missing high emissions caused by abnormal operating conditions, such as malfunctions, including for example emissions released from liquid storage tank hatches and vents.

The report said in 2015 the rate of methane leaked or vented was 2.3 percent of gross U.S. gas production – with a short-term climate impact roughly equal to that of CO₂ emissions from all U.S. coal-fired power plants in operation that year.

In contrast, the 2019 life cycle analysis of natural gas by the National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL), which is owned and operated by the U.S. energy department, says that the average national methane emissions rate is 1.24 percent.

EDF’s Leyden says “we really need to move towards a more direct measurement type of programme.” Such measurements can be done on the ground at the individual facility or using planes or drones with special equipment. These methods made the headlines in a recent New York Times story.

Another way to measure emissions is by satellite. EDF plans to launch its MethaneSAT in autumn 2022, to be operational in 2023. Other satellites have been developed to assess climate-harmful emissions, such as the Japanese Space Agency’s Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite (GOSAT Ibuki) or the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel-5P mission. EDF says its MethaneSAT will provide better coverage and measurement and be less expensive than the multi-function satellites built by government space agencies. “The concept is to have a global eye in the sky looking at methane emissions across the globe,” said Leyden. NASA is also planning to launch its Geostationary Carbon Observatory (GeoCarb) by 2023 to observe the concentrations of key carbon gases such as CO₂ and methane over the Americas.

According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Methane Tracker, emissions from Russia’s oil and gas industry are slightly higher than from the American industry. Each is responsible for roughly 15 percent of global methane emissions in that sector. However, the U.S. produces both more crude oil and natural gas.

Looking at existing studies, Germany’s Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) compared the methane emissions across the value chain of natural gas arriving in Germany in a report earlier this year. The institute put a focus on the United States, because there is a lot of available data. Compared to that the data, availability for Russia is very poor, says Stefan Ladage, geologist at the BGR. “Looking at the compiled literature in our study, methane emissions along the value chain from U.S. LNG are higher than those from Dutch or Norwegian pipeline gas, as well as Russian pipeline gas – bearing in mind that data availability is not as good in Russia,” he told Clean Energy Wire.

Aside from methane, natural gas production, liquefaction and transport is an energy-intensive endeavour and leads to a considerable volume of CO₂ emissions, for example from compressors. There are some studies assessing the full climate footprint of natural gas used in Europe and comparing different regions of origin, but without independent data, the climate footprint of natural gas from different regions can quickly become a controversial issue with the potential for politicisation.

The U.S. government published an analysis in 2019 and found its LNG to have a climate advantage over LNG from Algeria, pipeline gas from Russia and regional coal used in power plants in Europe. “We continue to see benefits of LNG,” commented the energy department’s Bennett. “We have done a very good job of making sure that we have a low-carbon footprint within our industry.” However, the government used Appalachian region shale gas in its U.S. scenarios, which has a low methane leakage rate compared to other regions or the country’s average.

In contrast, a 2017 thinkstep report commissioned by Nord Stream 2 AG sees the advantage with natural gas transported through the pipeline currently being built in the Baltic Sea. Aside from the modern pipeline, the study assumes a “new gas field in northern Russia” with “very efficient technologies”, which results in very low emissions during production.

“We stand behind our work here in the U.S. and Russia can provide their information as well,” said Bennett when asked about the comparison. “At the end of the day, when the EU thinks about emissions of gas from the different origins, you have to make sure that the factors are equal on all settings.”

One also needs to take into account which fuel the imported LNG replaces. Studies comparing the climate footprints make assumptions for “European domestic coal” which do not reflect the reality in many countries. In Germany, for instance, domestically mined coal is emission-intensive lignite. The hard coal the country imports – its mining in Germany ended in 2018 – often comes from far-away suppliers like Russia or Colombia. A recent study also shows that methane emissions from coal mines could be greater than previously thought.

Industry flares massive amounts of gas as infrastructure lacks

Aside from venting and leakage of methane, there is another issue – the one that was so clearly visible from Sue and Jim Franklin’s front porch: flaring.

It is a matter of debate whether the emissions caused by flaring can be counted towards the climate footprint of U.S. natural gas arriving in Europe. “In our view, the emissions that result from flaring associated gas are part of the oil value chain, not natural gas, because the associated gas is not used,” says the BGR.

EDF’s Leyden argues that it is all part of the same system. “The point is: if you’re drilling for oil, you need to be managing your gas as well as your oil. We don’t tolerate oil leaking onto the ground and we shouldn’t tolerate natural gas leaking into the atmosphere.”

Driving through the vast oil and gas regions in Texas, burning flares are almost constantly visible across the landscape. They may be the most illustrative sign of the industry’s activity, and serve as a beacon for public objection to its operations. At the well head, the flares can be necessary for maintenance and emergency reasons, or during start-up in the first days after well completion. They are also used in plants as an industrial incinerator to burn waste gases like hydrogen sulphide.

In regions with high levels of associated gas, like the Permian or Texas’ Eagle Forde Shale, the problem is much greater. Oil exploration in West Texas expanded rapidly in recent years, unlike the pipeline infrastructure necessary gather the natural gas that came to the surface with the oil and transport it off to regional hubs. Due to the extremely low gas prices, there was no economic incentive for companies to gather, store and use it. It was and continues to be simply cheaper to just burn it on the spot, rather than to put effort and funds into accelerated infrastructure development.

In terms of climate change, flaring is better than simply venting the methane, because the result is less-harmful CO₂ emissions. However, helicopter surveys from EDF’s PermianMAP project show that many flares are unlit – venting methane into the atmosphere – or only partially burning the gas.

The state’s oil and gas industry regulator – the Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) – has been very generous in granting permits to flare over recent years. In 2019, flaring in the Permian reached new records of 800-900 million cubic feet per day – or about five percent of total gas production – a report by energy research company and consultancy Rystad Energy shows. However, due to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on production and demand, Rystad estimates that flaring levels have fallen sharply in the first quarter of 2020 and will continue to decline throughout the year.

“So, interestingly, due to the low oil prices this flaring issue will be automatically resolved, just because activity will go down,” Artem Abramov, head of shale research at Rystad Energy, told Clean Energy Wire. “A lot of operators have very nice emissions charts showing that they improved a lot on their emissions intensity, but the real driver is simply the slowing activity.”

Industry starts to see climate-friendly production as competitive advantage

The gas industry, meanwhile, is increasingly tackling greenhouse gas emissions. Rystad’s Abramov said that operators have worried about issues like flaring, because “they were getting so much pressure from their investors over the last three or so years in regards to ESG [sustainability criteria for investments] and climate change topics.”

EDF’s Leyden said it is mostly the world's largest publicly traded oil and gas companies – also known as supermajors – and larger independents that “understand that controlling their methane emissions is part of proving that natural gas can continue to be part of a transition towards a low-carbon economy and ultimately impacts their social license to operate.”

Work on the methane strategy in the European Union certainly does not go unnoticed across the Atlantic. The EU delegation in Washington, D.C. is in talks with the oil and gas industry about methane emissions, an EU official told Clean Energy Wire. “We invite them here and they come in big numbers. They are very interested in that conversation.”

The next generation of proposed LNG export facilities is already advertising efforts to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from planned operations. They see it as an advantage over competitors especially vis-à-vis transatlantic customers.

“Europe is one of our most promising export markets, given that we will have the lowest carbon footprint among LNG export terminals in North America, if not the world,” said Omar Khayum. The CEO of Annova LNG told Clean Energy Wire that his planned export facility in Brownsville, close to the Texas-Mexico border, will have access to low-cost gas supply from the Permian Basin. Annova LNG plans to use electrically driven compressors fuelled with 100-percent carbon-free renewable energy, said Khayum. The project has yet to land contracts with customers, reports the Houston Chronicle, and it has seen heavy opposition from neighbouring communities, fishermen, environmentalists and Native Americans.

Like the U.S. administration, Khayum argued for natural gas as a way to reduce emissions in receiving countries. “We look forward to supporting the downstream reduction of greenhouse gases through displacement of coal- and oil-derived power globally.”

Sue Franklin, now in her new home town of Fort Davis, would rather support the build-out of renewables in Texas than the continued development of fossil fuels. “I think it’s very important to move towards renewable energy,” she said. “I would have let them put a hundred windmills on my property, rather than any of those wells. Or solar panels. Either one. But I don’t want those wells.”