Geared-up Germany enters second winter without Russian gas

Brimming gas stockpiles

Before the launch of Russia's war on Ukraine and the halt to a large share of energy supplies, Germany was particularly dependent on Russian fossil fuels, especially natural gas that arrived via pipelines. The energy crisis dealt a heavy blow to Europe’s biggest economy but, overall, the country emerged from the first winter without Russian gas relatively unscathed: Contrary to widespread fears, it didn’t experience gas shortages, nor large-scale social unrest. Alternative supply sources, saving efforts and warm weather all helped to avert a shortfall during the winter following on the 2022 energy crisis.

Germany and Europe now enter the heating season 2023/2024 much better prepared and more confident than last year – with new sources of supply, and storage facilities filled sooner. And the weather may once again lend a helping hand, with an increasing probability that Europe will see another mild winter, according to the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service.

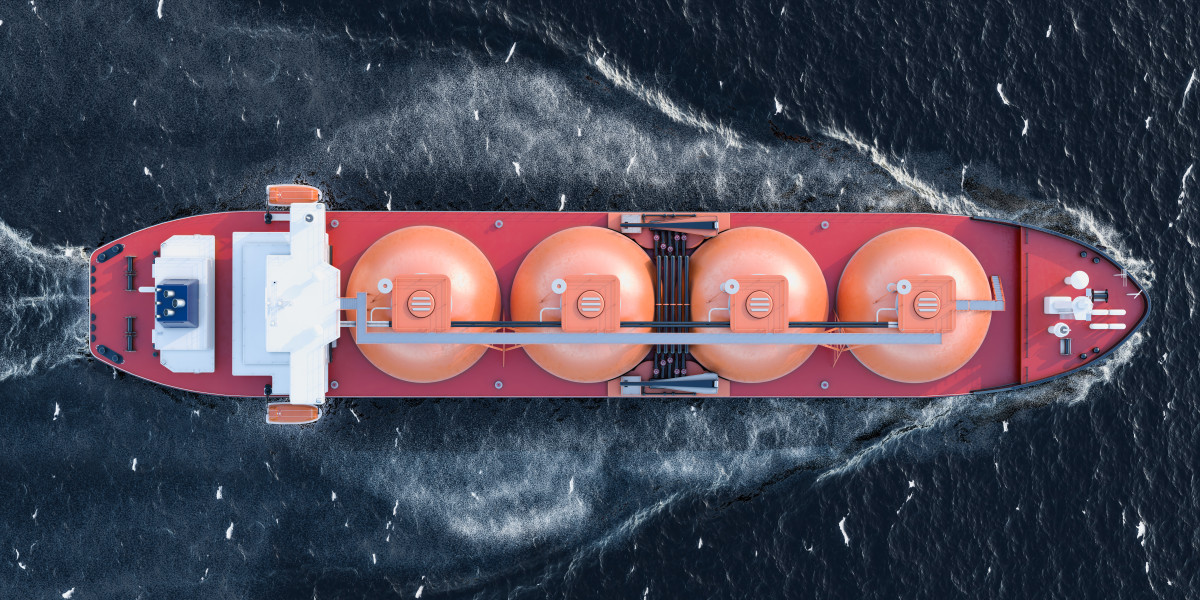

Capacities for importing liquefied natural gas (LNG) have already been increased in Germany and other European countries, and more floating LNG import terminals are set to be added this winter.

Gas storage levels in Germany reached about 100 percent by early November, the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) said. “The situation at the beginning of winter is much better than last year. Storage units are filled well and imports, as well as savings, remain stable,” BNetzA head Klaus Müller said. However, it was “still too early to give the all-clear signal,” he added, arguing that “a very cold winter” could still lead to a spike in gas consumption. The BNetzA’s modelling found that cold snaps with average daily temperatures below -10 degrees Celsius, as it last happened in 2012, could trigger a fast depletion of gas stocks.

At the same time, a cut to Russian deliveries to southeastern Europe could mean that Germany will have to assist states in the region in case of a shortfall. The agency calculated that gas exports through Germany to the region could amount to some 20-gigawatt hours. A “worst-case-scenario,” in which a domestic demand spike coincides with higher exports and insufficient imports “could mean that the existing demand is not fully met.” While new import infrastructure allowed the country to reach a storage level of 99.65 percent by November, gas customers still should make sure to moderate consumption wherever possible, Müller said. “Nobody should freeze. At the same time, we ask people to critically assess where they can reduce their consumption.”

The “alert level” for gas supply, the second level in the country’s three-step emergency gas plan that was triggered in June 2022, remained in place as of November 2023.

More on the Ukraine war's impact on energy security

Gas markets anxious about heating season

The sabotage of the Nord Stream pipeline, in which the gas transport link between Germany and Russia in the Baltic Sea was badly damaged in September 2022 - and it is still unclear who is responsible - has exposed significant risks to the safety of Europe’s energy infrastructure. These were reinforced after another incident on a Baltic Sea pipeline in October 2023, when the Balticconnector pipeline between Finland and Estonia was taken offline due to a leak, for which sabotage is suspected. Norway, Germany’s new largest gas supplier, and other states subsequently heightened its security level and increased its navy presence around marine energy infrastructure.

Germany has conducted test runs for a possible gas supply crisis, aiming to practice what would happen in case supplies must be rationed. The country "is much better prepared regarding this winter than it was last year," grid agency head Klaus Müller said. "We can certainly be optimistic, but it is still too early to sound the all-clear." The economy ministry also updated its "Natural Gas Emergency Plan" to include the experiences gained last year.

The EU as a whole is also “reasonably well-prepared” for the coming winter season, according to a report by the Bruegel think tank. “Demand cuts, alternative supply, and the green energy rollout mean the EU likely has enough gas for winter, even if Russian supplies are cut completely,” the researchers said in early October, adding that the EU met its 90 percent gas storage target two months ahead of a November deadline. “Notwithstanding these developments, Europeans should not be complacent. Fears about gas shortages or power cuts have receded, but a gas price that is persistently higher than in other markets and ongoing price volatility could still have repercussions for the EU industrial structure and economy,” Bruegel said.

Volatility in the gas market became apparent in mid-October, when gas prices shot up to the highest level in eight months in response to the attack on Israel and the Balticconnector incident. “Even though stockpiles are high and demand is weak, the market is anxious about winter,” according to Bloomberg’s Stephen Stapczynski.

Coal plants in reserve to secure supply

Germany last year decided to allow lignite power plants that had already been in a reserve to re-enter the market in order to help secure electricity supply and save gas during the heating period. The policy will be continued this winter. Other countries in Europe took similar precautions to bolster their supply security. France, for example, also extended the life of its two remaining coal-fired power stations until the end of 2024.

The German government said reactivating coal plants from the reserve will not affect the country’s coal phase-out, which is scheduled to be brought forward to 2030, if possible, from its planned 2038 date. However, state governments in eastern Germany have voiced concerns over whether the earlier exit date is still viable, given the new threats to supply security.

Economy minister Robert Habeck in mid-October also announced that the reactivated plants from the reserve capacity will be decommissioned for good in 2024, as the country will then have sufficient LNG import capacity to cope with lower pipeline-based gas supplies. “The infrastructure will be ready by then and that’s when we no longer need any additional coal plants. That’s the plan,” Habeck said. He added that, even though Germany is likely to get through the winter without trouble regarding the power supply, coal plants still act as a “safety net” for the unlikely event of a shortfall.

After the winter, the German government plans to evaluate whether the measure has led to additional greenhouse gas emissions and, if that is the case, make a proposal on how to compensate them. An analysis by consultancy Energy Brainpool published in early 2023 found that the “intensive use” of coal plants during the energy crisis caused Germany to emit nearly 16 million tonnes of CO2 more than it would have without it (out of a total of some 750 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions in 2022).

Reconnecting deactivated coal plants back to the grid had also been criticised against the backdrop of Germany’s nuclear power phase-out, which was finalised in April 2023. The government had delayed the end of nuclear power because of the energy crisis. Germany’s economy ministry estimated the emissions reduction benefit of the three additional months of nuclear power to range somewhere around 1.3 million tonnes of CO2, compared to producing the same amount of electricity with coal.

A winter of discontent?

The German government capped electricity and gas prices under its energy "price brakes" and cut the VAT for natural gas in a bid to protect consumers from skyrocketing costs during the energy crisis. The price caps are currently set to run out at the end of 2023, but the government is in talks with the EU to extend them until the end of the heating season in April as an "insurance against rising prices."

The government last year also launched a campaign urging citizens to save energy. But few households turned down their heating despite sharply higher prices, an analysis of consumption patterns found. Overall heating energy use went down more than ten percent in German households in 2022, but this was largely due to the mild winter. Adjusted for temperatures, heat energy use fell by little more than one percent – partly because it is hard to reduce consumption in badly insulated buildings, according to non-profit consultancy co2online. Household gas prices in Germany had nearly halved by October 2023 since their peak about one year earlier, but the share of households under financial pressure from higher energy costs has risen steeply since the onset of the European energy crisis in 2022. The number of households paying more than 10 percent of their income on energy had jumped from 26 percent to 43 percent between March 2022 and June 2023, according to a report by the country's Expert Council for Consumer Affairs. Concerns about inflation, which is mainly driven by energy prices, has topped the list of citizens’ worries in many European countries. In Germany, a large majority of citizens say they fear that rising living costs will erode their standard of living, fuelling fears of social decline.

In early October, the parties of Germany’s government coalition suffered heavy losses in two state elections in economically strong Hesse and Bavaria in western and southern Germany. The far-right populist AfD celebrated significant gains, contradicting the common perception that the party is largely confined to disadvantaged voters in poorer eastern Germany. The flagging economy, climate policy and the energy transition, as well as immigration, had been the most important topics for voters.

Opposition to climate action

Signs of discontent among parts of the electorate over many government policies had been rising even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine amid increasing inflation throughout 2022, which hit Germany and many other countries just as they were coming out of the socially stressful and divisive coronavirus pandemic. The government’s handling of the war then fuelled further dissatisfaction, with some voters saying the coalition was not resolute enough in supporting Ukraine, and others arguing that Germany should not oppose Russia, not least due to the negative economic and energy supply effects this would likely entail. The latter particularly included voters of the far-right AfD.

The party’s success is likely to fan the debate about the impact of ambitious climate policies and emissions reduction efforts initiated by the coalition of the SPD, the Greens and the FDP. Introducing a law on banning fossil fuel heating amid skyrocketing energy prices had been a constant source of disputes among the government parties. The warring made the three-party government prone to attacks from the opposition CDU/CSU conservative alliance, as well as from the AfD, which claimed that the coalition ignored the concerns of many citizens. The strong performance of the climate-sceptic AfD is reinforcing concerns among centrist parties about the election year 2024, when both the European elections in spring and three state elections in eastern Germany in autumn could further elevate the party, which rejects all emissions reduction efforts and advocates the restart of Russian gas imports.

Fears of permanent damage to industry persist

The energy price hike not only put a strain on household budgets but also greatly affected Germany’s sizeable industrial sector, as well as the economy at large. Many industrial companies in the country, in particular energy-intensive ones such as chemicals producers or steelmakers, had bet on the availability of cheap Russian pipeline gas. The energy crisis - compounded by tenacious supply chain problems, especially in the automotive industry - hit many companies at a critical stage of their plans to transition away from fossil fuels. While the costs associated with industry decarbonisation added to companies’ woes, many also acknowledged that reducing reliance on fossil fuel supplies and increasing energy efficiency would ultimately make energy cheaper and more secure.

While fears of imminent de-industrialisation of Europe’s largest economy largely turned out to be overblown, economic growth remained significantly depressed throughout 2023. The government revised its growth expectations in its autumn projection and stated that Germany will recover more slowly from its recession and achieve lower growth in 2024 than previously expected. Some industries, for example construction, recorded the worst business climate in several decades, not least owing to rising interest rates and a much more difficult investment environment, leading the government to relax energy efficiency standards.

Germany, in part because of the energy crisis, is currently debating whether it needs to subsidise the electricity used by heavy industry to maintain competitiveness. The economy and climate ministry is considering a plan to spend billions of euros to lower power prices for energy-intensive companies if they promise to decarbonise, and to stay within the country. Economy minister Habeck even suggested Germany should consider lifting its restrictions on new state debt, given the high costs of industry decarbonisation amid an economic downturn. Many economists reject the plans, arguing they could easily turn into permanent subsidies that delay necessary structural change.

However, the government has stressed that the EU as a whole is under pressure to respond to industry subsidy schemes rolled out elsewhere in the world. This is particularly true in China and the U.S., where the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), created to woo investments in green technologies, has caused disputes over a trade conflict in Berlin and other European capitals. Chancellor Scholz in October insisted that effective climate action in Germany and Europe requires economic growth to prove it does not undermine prosperity, and that it opens a perspective for industrial success in the future. Together with his French counterpart, president Emmanuel Macron, Scholz repeatedly said that the EU will require a concerted effort to implement decarbonisation measures while remaining competitive. The two countries, which represent about 45 percent of the EU’s economic output vowed closer cooperation on bolstering a strong and sustainable industry and create new industrial champions.