Germany, EU remain heavily dependent on imported fossil fuels

Content

- Russia’s war against Ukraine puts import dependence in spotlight

- What impact will the energy transition have on imports?

- European Union’s import dependence

- Germany's import dependence

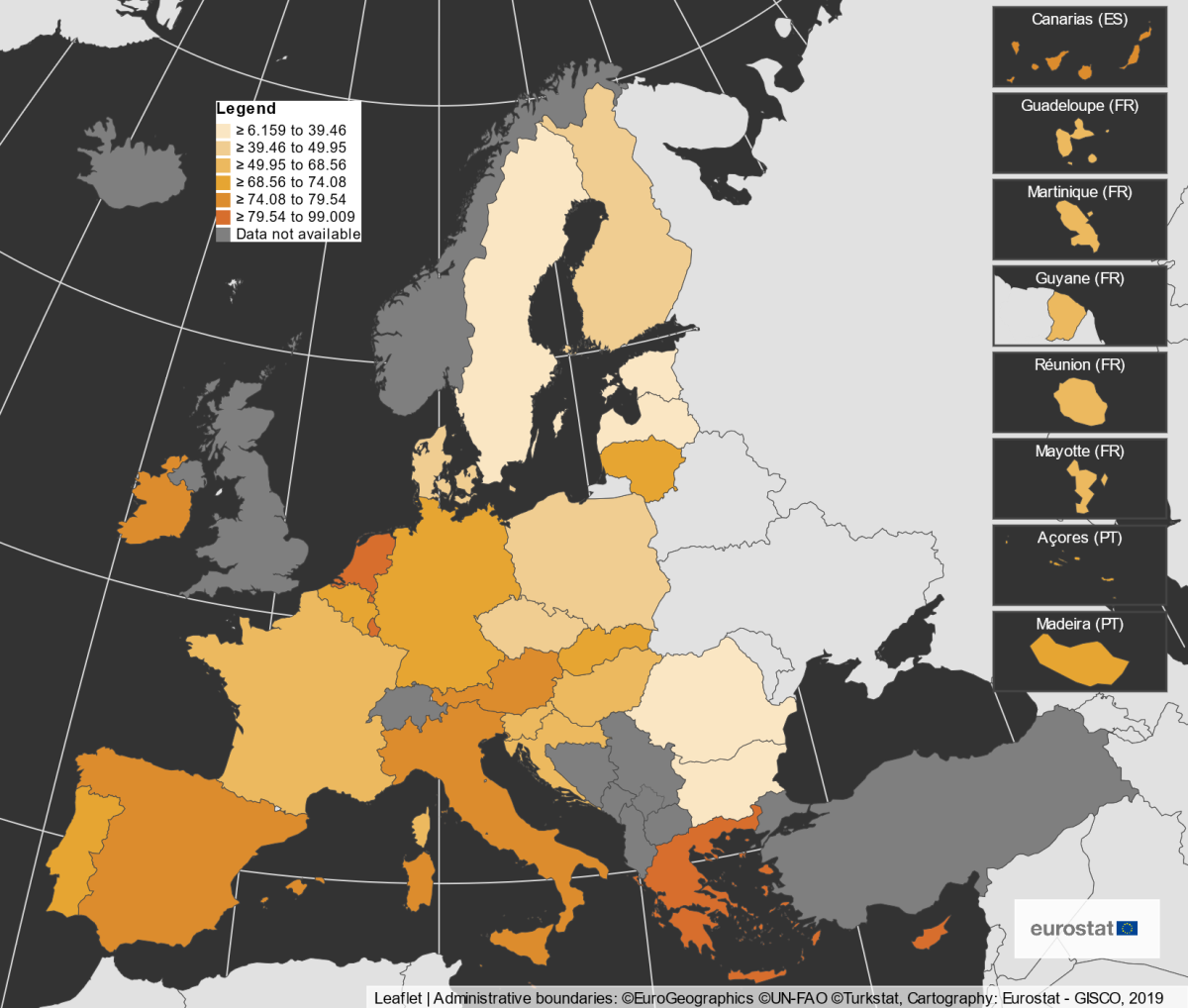

In 2022, the European Union imported 62.5 percent of the energy it consumed – the highest level of dependency since at least 1990 – while its own production and stock changes satisfied only 37.5 percent of its needs. Germany’s energy import dependency was still higher at 68.6 percent – an increase compared to the previous year’s 63.4 percent.

With an increasingly integrated European energy system, the significance of a country-focused analysis of import dependence will decline, and an EU-wide one will come into focus. However, the consequences of the war against Ukraine and the energy crisis also showed that governments often still see energy security as an issue to be tackled at the national level.

1. Russia’s war against Ukraine puts import dependence in spotlight

The global energy crisis fuelled by Russia’s war against Ukraine has put a renewed focus on the debate about Europe’s and Germany’s dependence on imported fossil fuels, and especially their heavy dependence on one single supplier: Russia.

Until the end of 2021, Russia was the main supplier of oil and natural gas to the EU. It was also Germany's main supplier of oil, gas and hard coal. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, imports from Russia decreased substantially due to sanctions from both sides and the war’s influence on trade and infrastructure (see below for details).

2. What impact will the energy transition have on imports?

Overall dependence on energy imports will change dramatically for some countries as the energy transition progresses. The rapid expansion of renewable energy is likely to alter the power and influence of certain states and regions and to redraw the geopolitical map in the 21st century, said a 2019 report published by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

The plan to reach climate neutrality by 2045 should all but eliminate fossil fuels from Germany’s energy mix. The German government has introduced interim greenhouse gas emission targets for the years until 2040 with the Climate Action Law. The European Union as a whole aims for climate neutrality by 2050.

As fossil oil and gas are being phased out, many see the need to partly replace them with synthetic fuels. Renewable electricity is converted into hydrogen, methane or synthetic petrol (power-to-x) to serve as energy sources in certain areas, for example in industry, road freight transport, shipping or seasonal energy storage. According to several research reports and government strategies, Germany will have to import significant amounts of these green fuels, because space for generating electricity from renewables is limited in the country and power-to-x fuels could be produced significantly cheaper in other regions of the world. Thus, while Germany will likely reduce its overall dependence on energy imports, it will continue to rely on supply not only from within the European network but also from third countries.

3. European Union’s import dependence

The EU produces large parts of its energy domestically, with about 41 percent from renewables and 31 percent from nuclear in 2021, and the rest mostly from solid fuels like hard coal and lignite, and some from natural gas and crude oil.

Still, most energy needs are met through imports. The dependency on imports increased significantly from 2021 (55.5%) to 2022 (62.5%). [Eurostat makes available the energy import dependency broken down by product for the years since 1990, which you can find here.]

Together, imports of oil, gas and solid fuels made up about 28 percent of total extra-EU imports in 2022 (% of trade in value). This was a substantial increase over the previous year (18% in 2021) as the energy crisis drove up prices on global markets.

Russia was the main extra-EU supplier in 2021 (by trade value: 24.8% of petroleum oil, 48% of pipeline gas, 47.9% of coal), creating “an over-reliance on a single, untrustworthy supplier,” as the European Commission phrased it. However, the landscape of EU energy imports changed dramatically during the energy crisis. By the third quarter of 2023, Russia supplied only 3.9 percent of petroleum oil, 16 percent of pipeline gas (Norway now the largest supplier, 48.6%), and no coal. (Full year data for 2023 not yet available at time of publication.)

Graph shows extra-EU imports of petroleum oils to the EU from main trading partners in Q3 2022 and Q3 2023. Source: eurostat 2024.](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/eurostat-eu-imports-petroleum-oils-partner-december-2023.png?itok=43fn984r)

The reduction of fossil gas imports from Russia was especially in the spotlight over the past two years. The 150 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas (both LNG and pipeline) imported to the EU from Russia in 2021 was nearly halved (to 80 bcm) in 2022 and fell by a similar share (to 43 bcm) in 2023. "In short, EU dependence on Russian gas fell from 45 percent in 2021 to only 15 percent in 2023," said the Commission. Countries such as Austria in early 2024 still source a large share of their gas from Russia, while planning to follow others in fully weaning themselves off Russian supplies. NGOs have called on EU countries to fully stop imports from Russia.

Norway and the U.S. became the EU's main gas suppliers in 2023, representing 30 percent and 19 percent of total gas imports, respectively. While quarterly imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) more than doubled between early 2021 and mid-2022, pipeline imports fell considerably. [Think tank Bruegel has also compiled information and a dataset on European gas imports.]

While the EU imposed sanctions on oil imports from Russia, there is no ban on natural gas deliveries. Reuters in April 2024 reported that western European governments have increasingly substituted the country's pipeline supplies with its liquefied natural gas (LNG). The news agency's analysis of data found more than a tenth of the Russian gas formerly shipped by pipeline to the European Union has been replaced by LNG delivered into EU ports.

Graph shows extra-EU imports of natural gas in gaseous state to the EU from main trading partners in Q3 2022 and Q3 2023. Source: eurostat 2024.](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/eurostat-eu-imports-natural-gas-gaseous-state-partner-december-2023.png?itok=m5_bEDWU)

Energy import patterns vary widely across the EU member states. While more than 85 percent of imports in countries such as Malta and Cyprus were petroleum products in 2021, over a third was gas in Hungary and Italy. The total import dependency rate in 2021 ranged from one percent (Estonia) to more than 90 percent (Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta).

Estonia’s high degree of energy self-sufficiency is based on domestically produced oil shale, an energy-rich sedimentary rock that can be either burned for heat and power generation or used for producing liquid fuels, according to the 2019 International Energy Agency (IEA) country report.

4. Germany's import dependence

Graph shows: Comparison of use of primary energy sources and the share of domestic production and imports 2012 and 2022 for Germany. Image: CLEW 2024.](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/german-energy-sources-import-dependency-2012-and-2022.png?itok=NkvAyXuI)

a) Oil

Oil consumption peaked at the end of the 1970s, but it remains Germany’s most important primary energy source. Oil covered 35.9 percent of the country’s primary energy use in 2023. Oil was mostly used as a transportation fuel, and only a small fraction was used for power production.

According to the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR), about 98 percent of Germany’s primary mineral oil consumption had to be imported in 2022. The country’s domestic crude oil output from 43 oilfields amounted to 1.7 million tonnes that year.

In 2022, Germany imported 88.2 million tonnes of crude oil (the country also imports additional mineral oil products). In total, 31 countries supplied crude oil to Germany.

In 2021, Russia was by far the largest supplier, delivering 34.1 percent. (U.S. 12.5%, Kazakhstan 9.8%, Norway 9.6%). However, the situation changed significantly starting in 2022.

Official data show that for the full year 2022, 25.4 percent of crude oil came from Russia, which during that period was still the largest supplier by far (followed by the U.S. with 13.7%). However, due to an EU embargo and Germany’s pledge to end crude oil imports from Russia, supplies ceased completely at the turn of 2022/2023. From 5 February 2023, the EU also banned the import from Russia of refined petroleum products, such as diesel fuel.

What impact will the energy transition have on oil imports?

Transport accounts for most of Germany’s oil consumption, which has more or less steadily declined since the late 1990s. The transition to renewables, which has largely been focused on the electricity sector, has had little impact so far. Still, the energy transition has reduced the already minor role of oil in power generation (1% share in 2023 gross power production), because cheap renewable energy has crowded out oil-based generation.

The Climate Action Law stipulates that the transport sector should almost halve emissions by 2030 compared to 1990, which means oil use must decrease significantly. One key element of Germany's climate policy to get there is electrifying the passenger car fleet, where the government targets 15 million EVs on Germany's roads by 2030. For certain modes of transport – such as freight trucks – imports of synthetic fuels could become necessary.

Official scenarios for Germany's future energy system foresee petrol and diesel use for passenger cars and trucks to be reduced by about a quarter in the decade from 2020 to 2030, and then down to about a third of 2020 levels by 2040.

Germany aims to reduce final energy consumption in transport to 90 percent of 2005 levels by 2020 and to 60 percent by 2050 with the help of more efficient engines. However, consumption has remained unchanged (with some ups and downs in-between). More traffic both regarding passenger and freight transport, as well as bigger vehicles, have eaten up gains in efficiency.

b) Gas

Gas covered a little less than a quarter of Germany’s primary energy use in 2023, making it the country’s second most important energy source. Germany is among the world’s biggest natural gas importers – around 95 percent of its gas consumption is met by imports, according to the BGR. In 2022, the country produced 4.8 bcm of natural gas, but according to geologists, the fields are nearing depletion. Domestic natural gas production has been falling since 2004 and will likely cease altogether in the course of the 2020s.

While Russia’s war against Ukraine has reignited the debate about the possibility of unconventional fracking in Germany, legal restrictions, opposition by the population and the current government, and the goal of climate neutrality by 2045 make its use very unlikely.

Germany imported 3,524 petajoules (PJ) of natural gas in 2022, according to the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA). The halt of pipeline deliveries from Russia in September that year caused this massive decrease from the 5,000 PJ imported in 2021.

The share of imports by country remained unclear for several years. Due to data privacy regulations, BAFA stopped publishing import volumes by country in 2016. However, the economy and climate ministry said in 2022 that before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, 55 percent of gas imports came from Russia, 30 percent from Norway and 13 percent from the Netherlands.

Germany stopped receiving pipeline gas from Russia in late August 2022. While there is no EU embargo on natural gas, the government said shortly after the start of the war that it intended to reduce the share from Russia significantly over the course of two years. However, Russia itself reduced supplies step-by-step and halted them completely in the summer of 2022, shortly before explosions destroyed the Nord Stream pipelines – the only direct gas links between Germany and Russia. [Also read the factsheet Gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 links Germany to Russia, but splits Europe.]

While there had been wide-spread worries of a severe gas shortage, especially in the winters of 2022/2023 and 2023/2024, it did not materialise, thanks to milder temperatures (less need to heat homes) and the government's costly efforts to secure alternative supplies.

Energy industry association BDEW data show that over the course of 2023 Norway was the main supplier of natural gas to Germany with a monthly share of around 35 percent, followed by the Netherlands with about 30 percent. Germany is also supplied via LNG terminals in neighbouring countries, where the fuel is regasified and fed into the natural gas pipeline infrastructure. BDEW said that in some cases it is difficult to attribute the origin of the gas that crosses the borders into Germany. For example, pipelines from Austria or Switzerland can contain Russian natural gas (via Ukraine) as well as Algerian natural gas or LNG from Italian LNG terminals. "Therefore, plausible estimates and assumptions must be used to calculate the origin mix," BDEW said.

A 2024 Reuters analysis said that ports in Spain, France and Belgium continue to receive LNG shipments from Russia, and this sometimes included transhipments, when LNG switches ships in an EU port before sailing on. In 2023, Germany imported 48.6 percent of its gas via pipeline from Belgium, France and the Netherlands. Reuters said that as much as 13.7 percent of gas in the German grid could be Russian, in a scenario where those countries passed on as much Russian LNG as possible. The reality is probably less when accounting for national consumption and supply mixes, said the news agency. "Physically, it is conceivable that Russian gas molecules could come to Germany," a spokesperson from the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) said. "We do not know whether German importers buy Russian LNG quantities directly. It would not be prohibited," the spokesperson added.

Environmental NGO Urgewald has also criticised that Russian LNG continues to arrive in the Netherlands and Belgium, parts of which also make their way to Germany.

(CLEW translation) Image shows trend of origin of natural gas consumed in Germany by country, monthly in 2022 and 2023. Source: BDEW (CLEW translation)](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/bdew-origin-gas-2022-2023.jpg?itok=Tlt4HogN)

Gas used to be imported to Germany exclusively via pipelines, but the war prompted chancellor Olaf Scholz to decide to set up a domestic import infrastructure for LNG. The first floating terminal was built in record time and went online at the end of 2022. There are now three facilities in operation, with three more under construction. In 2023, about five percent of total monthly imports arrived at German LNG terminals.

Several reports have criticised the size of Germany’s LNG infrastructure plans. These are “massively oversized” and state involvement means that taxpayer money is used for what could eventually become stranded assets, said a report by think tank NewClimate Institute in December 2022. In another report, the NGO DUH and the Heinrich Böll Foundation said Europe should avoid “gigantic overcapacities” by coordinating the development of LNG infrastructure. Following the second winter without any signs of a gas shortage, a 2024 report by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) called on the government to re-evaluate and cut back its LNG infrastructure expansion plans.

What impact will the energy transition have on gas imports?

Germany’s plan to become climate neutral by 2045 also means fossil gas will have to be largely phased out by then. Currently, most of the gas is used in the industrial sector (e.g. for power and heat supply, or in chemical processes), followed by private households (mostly heating), public power and heating supply, and manufacturing and trade. Natural gas consumption in transport is marginal. The lion's share of gas is burned to produce heat, and only a fraction is used to produce electricity.

Germany’s government and many experts see natural gas as a bridge to a low-carbon economy because it produces much less CO₂ emissions when combusted than either coal or oil. However, fugitive emissions, like the leakage of methane during production and transportation, need to be taken into account to evaluate total lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions. Gas complements fluctuating power supply from renewables rather well, because modern gas-fired power stations (unlike coal) can switch from idle to full output within minutes if necessary. Thus, Germany wants to build new gas power plants, later to be converted to hydrogen.

The former German government said that the planned exit from nuclear and coal-fired power generation means that mid-term gas demand will increase. However, many analysts doubt that total natural gas demand will rise during the energy transition as efficiency increases and renewables, storage and ultimately renewables-based gases (such as green hydrogen) will cover more and more of the energy need across Europe. Projections for future EU and German gas demand vary widely, many foreseeing a decrease.

Power-to-gas as a way of converting electrical energy into methane or hydrogen for direct use or the long-term storage of renewable power have only been tested in pilot projects and have yet to be used on a larger scale. The federal government strongly bets on green hydrogen in its quest for climate neutrality, and says much of it will have to be imported. In a 2018 analysis, think tanks Agora Energiewende and Agora Verkehrswende also said that Germany would need the well-directed use of power-based synthetic fuels, including gas, in connection with a phase-out of conventional oil and natural gas to reach its long-term climate targets. The think tanks agree that large amounts must be imported.

c) Coal

Germany’s largest domestic fossil fuel source is coal, but its consumption has decreased a lot in recent years, with a rebound in 2021 and 2022 – first due to unfavourable weather conditions for renewables and high gas prices, then also due to government efforts to bring coal plants back to replace gas use in power production. In 2023, coal consumption dropped again, with lignite use at a record low.

Germany still extracts lignite (or brown coal) from opencast mines for power production on a large scale – 130.8 million tonnes in 2022 – and imports very little, according to the BGR. For years, Germany was the world’s biggest producer of lignite – which emits particularly high levels of CO₂ – and the country still has extensive deposits. Lignite covered 8.5 percent of Germany’s primary energy use in 2023. Most is burned for power generation (17% of Germany’s gross electricity production in 2023) or district heating.

Due to unfavourable geological conditions, German hard coal is not competitive on the international market, and subsidised hard coal mining ended in 2018. Germany now has to import all the hard coal it uses, mainly by the energy sector (e.g. for power generation: 8.6% of gross electricity in 2023) and for steel production. Hard coal covered nine percent of Germany’s primary energy use in 2023. [See the CLEW factsheet on coal for further details.]

In 2022, Germany imported 44.65 million tonnes of hard coal. Its leading coal suppliers were Russia (29.2%), the United States (20.8%) and Colombia (16.3%). Due to an EU ban, Germany ceased to import Russian coal in summer 2022. The association of coal importers said that “the very high – 50 percent – share of Russian coal in total imports can be replaced by coal from other exporting countries,” but there were logistical issues to be tackled, such as ports running at their limits.

What impact will the energy transition have on coal imports?

The new coalition government decided to pull forward the phase-out of coal to 2030 (from 2038), and has already made a deal with the western German mining region. However, eastern states are reluctant to agree to an earlier phase-out. The former government had decided a shutdown timetable for lignite plants and introduced auctions to compensate hard coal plant operators for early decommissioning. The current government has long delayed a report to re-assess these plans, also due to the energy crisis and to efforts to have more coal power for a limited period of time. By February 2024, the report had not been published.

Germany also aims to have a largely decarbonised electricity supply by 2035, and projections show very little coal will be used by that year. In addition, the rising carbon price in the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) means that coal-fired electricity generation and heating becomes increasingly uncompetitive. Research reports show coal is set to be pushed out of the market by 2030.

However, supply security needs could force Germany to keep coal plants online longer, until sufficient gas-fired units can be brought online. In the past, critics of Germany’s current push to reduce the use of CO2-intensive lignite had said the country should not abandon its only sizeable domestic energy source. Mining union IG BCE, for example, warned in 2015 that the Energiewende can only succeed if Germany doesn’t play “Russian roulette” with its supply security. The union argued that “domestic energy sources ensure German companies do not become even more dependent on price and supply fluctuations on world markets. Our lignite can guarantee this in a balanced energy mix.”