How Germany is greening its growing freight sector to meet climate targets

Freight transport routes form the arteries of modern economies. City dwellers expect a constant supply of fresh produce on supermarket shelves and rapid online shopping deliveries to their door. Just-in-time deliveries are crucial for companies enmeshed in ever more complex production networks.

This is particularly true for Germany. The world’s fourth largest economy, famed for its industry and export prowess, is located at the heart of an increasingly integrated Europe. The safe, quick and cost-efficient transport of goods is vital to maintain its wealth and status as an economic powerhouse. Huge volumes of raw materials and industrial components enter the country on a daily basis via a complicated network of roads, rails, waterways and airports. Products “Made in Germany” – ranging from cars to machinery and chemicals – are sent to markets across the globe. Additionally, a seemingly endless stream of trucks, trains, ships and planes transit the country, which borders nine other nations.

Little wonder that Germany’s transport infrastructure is extremely dense: It has around 230,000 kilometres of roads (without even counting city streets), a rail network covering 38,500 kilometres, and 7,600 kilometres of waterways.

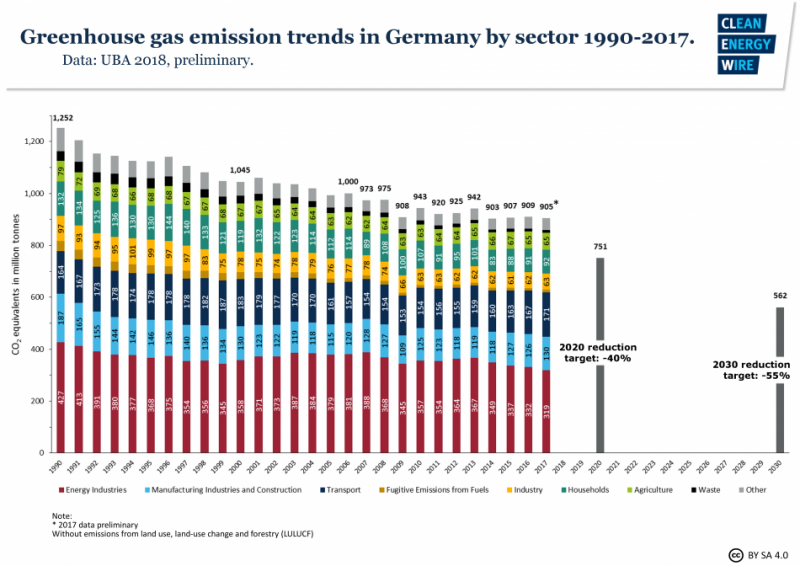

With this carefully planned infrastructure, it may seem surprising that energy transition pioneer Germany has barely begun to consider how freight transport will factor into its ambitious emissions reduction targets. There is certainly room to manoeuvre: while other sectors of Germany’s economy, such as energy and industry, have clocked up sizeable CO2 savings over the years, transport emissions have remained largely constant for 25 years.

Policymakers now agree in principle that the transport sector needs to change course. “Our big problem child is transport,” Chancellor Angela Merkel said in June with reference to Germany’s climate ambitions.

The current government reaffirmed Germany’s commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement targets for transport in its coalition agreement. But since taking office in March 2018, it has done little to decisively steer the sector in a more climate-friendly direction. Quite the opposite: when it comes to concrete steps to initiate the transition – such as pushing for tougher EU car emission rules or introducing of a blue badge to identify clean diesel cars – the transport ministry has been stepping on the brakes.

Climate collision course

Instead of greening the growing freight transport sector, the public debate has been dominated by the shift to electric passenger cars and the impact of this trend on the country’s iconic carmakers BMW, Daimler and VW, as well as their employees and suppliers. [The dossier BMW, Daimler, and VW vow to fight in green transport revolution has all the details.]

“The question of how to cut freight emissions has been neglected in Germany, because the future of passenger cars is currently much more pressing for industry,” Urs Maier, freight expert from renewable transport think tank Agora Verkehrswende*, told the Clean Energy Wire. “Freight offers huge potential for emissions reductions, but its growth rate is enormous and the exact path to decarbonise the sector remains unclear.”

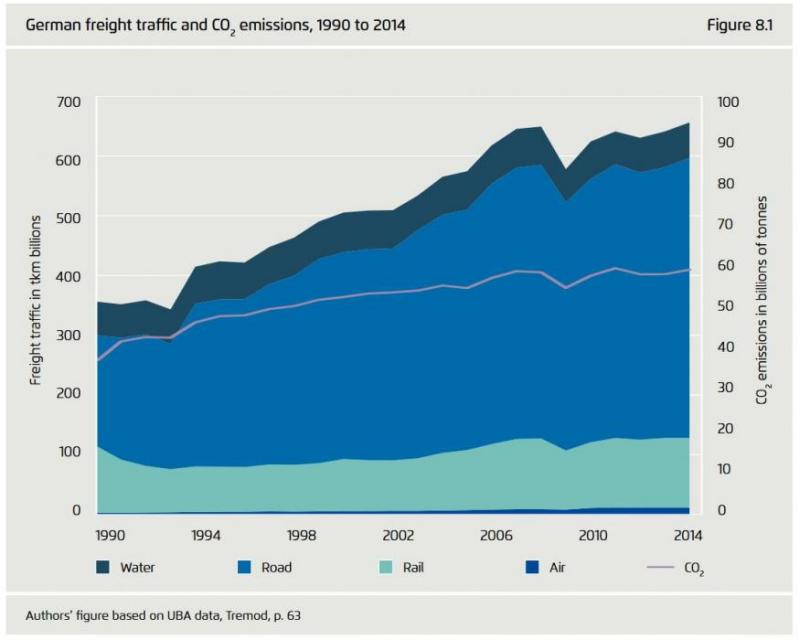

Its rapid growth will push freight transport inexorably into the limelight of climate policy. Between 1990 and 2014, total freight traffic volumes – carried on roads, by rail, on water and through the air – more than doubled to around 650 billion ton-kilometres, while CO2 emissions rose 60 percent to 59 million tonnes.

Germany’s transport ministry has forecast that by 2030, freight traffic will have grown 38 percent over 2010 levels. But by then, Germany wants to have cut its total emissions by 55 percent against 1990 levels. To achieve this, the government wants the entire transport sector – including both passenger and freight transport – to reduce CO2 emissions by at least 40 percent in little over ten years. Even many green transport proponents consider this an ambitious target.

But while cleaning up the transport of goods in the coming decade is already considered a daunting task, it’s only the beginning: by the year 2050, the entire sector will have to be “effectively greenhouse gas neutral,” if Germany is to achieve its official goal of reducing total emissions by 80 to 95 percent, according to the Federal Environment Agency. [The CLEW dossier The energy transition and Germany’s transport sector gives an overview of the entire sector.]

The details on how to reach these targets remain murky, but it is already evident that both energy savings and entirely new propulsion systems will be key to cutting emissions while freight volumes increase.

“In view of this growth, the decarbonisation of freight traffic can be achieved only if final energy demand drops significantly and fossil fuels are replaced by wind and solar power and by renewables-based fuels,” argues think tank Agora Verkehrswende.

The Federal Environment Agency says priority must be given to the “systematic shift of freight transport to the railways and for the Energiewende to bank on post-fossil design and fuels […] a transport transition must go hand in hand with an energy transition. Germany’s climate protection targets can only be reached with a greenhouse gas-neutral transport sector.”

But while the destination of a zero-carbon freight sector is set, Germany still lacks a detailed roadmap. This is true for all means of goods transport – trucks, trains, ships and planes.

Clean trucks - The heavier the trickier

Vans and trucks are by far the most common form of transporting good on land in Germany – and most CO2 intensive. Trucks make up 71 percent of freight traffic, dwarfing trains (18 percent), ships (9 percent) and air freight (2 percent).

Road transport will therefore be the most essential focus of emissions reduction. Experts agree on a two-pronged approach: shifting as much freight as possible onto cleaner modes of transport like rail and shipping for longer distances and small electric vehicles or even bikes within in cities, while putting cleaner vehicles on the roads.

Broadly speaking, the challenge of cleaning up road transport grows exponentially with the weight and range of the vehicles involved.

The “last mile” of urban logistics, i.e. delivering parcels from a transportation hub to residents and shops, can largely be covered by small electric vehicles already available, or even pedal power –Germany has several cargo bike pilot projects.

Electric vehicles are becoming popular for urban deliveries – famously, the German postal service’s Streetscooter. The idea was rebuffed by carmakers, but Deutsche Post DHL Group opted to buy a start-up to produce its own electric delivery van. To the surprise and embarrassment of Daimler and VW, the vehicle has been a spectacular success, and is now common sight on German roads. The postal service also sells the vehicle to third parties, and has ramped up annual production capacity to about 20,000 vehicles due to strong demand.

Deutsche Post DHL Group, which says it is the world’s largest mail and logistics company and runs approximately 92,000 vehicles worldwide, wants to operate “70 percent of our first and last mile services with clean pick-up and delivery solutions, such as bicycles and electric vehicles” by 2025. The company has also committed to reducing all transport-related emissions to zero by 2050.

Following this wake-up call, the incumbents have started to offer battery-electric versions of their own transport vehicles, starting with smaller models. For example, Daimler plans to start selling an electric version of its “Vito” van in 2018.

Combustion engine trucks still offer plenty of potential to save energy, and therefore emissions – for example by improving engine efficiency, making the vehicles lighter and more aerodynamic, or by avoiding empty trips through better logistics planning. Daimler says truck diesel engines could reduce emissions by 10 to 20 percent.

The EU is the only major market on the globe with no regulation on truck emissions, but it is currently planning efficiency targets, which could have a big impact. However, entirely new propulsion technologies will be indispensable to really make a dent in emissions in the future.

“All potential sources of CO2 reduction must be enhanced, from vehicle technology measures to renewable fuels to optimized vehicle operation,” according the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA).

It will be a while before the first trucks with alternative engines hit Germany’s roads in sizeable numbers. Daimler and VW’s MAN are currently racing to bring electric trucks to market, following the lead of Tesla, which presented its electric “Semi” in late 2017. The maker of Mercedes cars aims to start production of its “eActros” battery-electric heavy truck with a range of 200 kilometres in 2021. It has also unveiled two models for the US market.

But batteries will remain too heavy in the foreseeable future to power long-haul trucks on the distances they usually cover.

To reach the same range as a diesel-powered model with a standard 224 litre tank, an electric model would need a battery weighing 8 tons, according to Daimler. This is why it is still unclear how tomorrow’s emission-free trucks will be powered. The main options now are electric trucks drawing power from overhead wires on major routes, or combustion engines running on renewable fuels made with wind and solar energy (“Power-to-gas” or “power-to-liquid”). Daimler believes that engines powered by renewable hydrogen are the most promising technology, but is keeping mum on prototypes and a rollout.

“The intensive competition of different technologies for emission-free vehicles is set to continue in road freight traffic, where the race between trucks that run on overhead wires, engines using gas, fuel cell trucks, diesel trucks with power-to-liquid and pure battery trucks remains undecided,” says German industry association BDI. “It seems likely that several technologies and suitable combinations will become established, depending on primary use cases.”

Electric highways

Equipping Germany’s motorways with overhead power lines akin to those used by inner city trams and railways could cost taxpayers billions of euros, but also present a huge business opportunity for industry.

Following a pilot project, construction has begun on Germany’s first e-highway for trucks. In 2019, five test trucks will start using a 5 kilometre section of the autobahn in the state of Hesse. Engineering giant Siemens, the Technical University of Darmstadt, and five haulage companies are involved in the catenary (overhead electric wire) project [See factsheet Germany’s Siemens: a case study in Energiewende industry upheaval]

Powerful industry association BDI argued in its landmark 2018 study on climate policy that Germany will need to narrow down its mid-century climate target as soon as possible, because the decision will have massive repercussions on the investments required to achieve them, not only in transport. Until now, the German government has only set a target corridor, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80-95 percent by 2050.

To avoid that climate protection in Germany “fails dramatically”, Andreas Kuhlmann, head of the German Energy Agency (dena), recently recommended to quickly decide on 95 percent reduction, because policy decisions in the here and now depend on it.

The BDI study argues that Germany should equip the busiest 4,000 kilometres of its entire highway network totalling 13,000 kilometres with electric overhead lines for trucks in case it aims for an 80 percent reduction. A 95 percent emissions reduction – the most ambitious end of Germany’s target range – would require 8,000 kilometres of overhead lines, according to the BDI. “As things stand today, electrifying large parts of heavy freight traffic is only realistic with the deployment of catenary trucks. Despite the necessary infrastructure investments, this option is currently the most cost-efficient way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

But the industry association also warns that such a large infrastructure investment carries risks, because technological advances in batteries, fuel cells or synthetic fuels could make those options cheaper in the future. It recommends waiting five to seven years before a final decision is taken.

Catenary systems could save a lot of energy, because renewable power is used directly, avoiding conversion losses inherent in making synthetic fuels. Many experts say there might not be enough renewable electricity to power the entire transport system.

“The enormous energy consumption of the transport sector will require the generation of additional renewable electricity to reduce its CO2 emissions,” says Urs Maier of think tank Agora Verkehrswende. “The current rate of wind and solar capacity expansion – including the necessary expansion of power grids and storage systems – is too slow.”

Longer term, a catenary system would reduce billions of euros’ worth of synthetic fuel imports, and offer many other advantages, according to the German Energy Agency (dena). “Hybrid catenary trucks can significantly reduce local environmental emissions. The use of an electric powertrain would avoid all nitrogen oxide and fine particle matter from engine exhausts, and produce only minor noise emissions at low speeds.”

But the agency also points out a “chicken-and-egg” problem requiring strong public involvement: a catenary system must be used by many trucks, and can only be built if an extensive network already exists. “In contrast, trucks powered by fuel cells or liquid natural gas (LNG) can already be used economically with a limited number of fuelling stations, as long as their range is sufficiently large,” explains dena.

This decision is unlikely to be taken in Berlin alone. Germany’s role as a transit hub in the middle of Europe means the country has to work with its neighbours – a catenary system is simply not a workable solution if the powerlines end at Germany’s borders with nine other countries.

“The clean-energy propulsion option that will dominate heavy long-haul trucking is still unclear,” says Agora Verkehrswende. “The German federal government and the EU Commission must develop a coordinated propulsion system at the European level.”

Transport by rail – clean but limited

Transporting one tonne of goods per truck causes four times the emissions and uses five times the energy of trains, and Germany’s largely electrified rail system can already be used for long-distance freight transport. Rail transport made up about 18 percent of German freight transport in 2016.

But while rail is seen as an important part of lowering emissions overall, its potential in freight transport is somewhat limited, especially for shorter distances, where road freight dominates. In an ambitious scenario, rail freight could contribute about 30 percent of the country’s total freight transport by 2050, according to Germany’s Federal Environment Agency (UBA). This represents the maximum potential of shifting freight transport to rail and cannot be implemented without considerable expansion of capacities (lines, hubs, terminals) in comparison with current facilities, says UBA. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement.

Germany’s rail operator Deutsche Bahn – one of Germany’s largest power consumers – says that since the start of 2018 its long-distance passenger trains have been powered entirely by renewable electricity, and freight clients can choose to have their goods transported with green electricity as well. In 2017, however, the share of renewable power in freight transport by rail was only 27 percent, according to Deutsche Bahn. In 2017, 44 percent of Deutsche Bahn’s power mix came from renewables, about one third from coal, 12 percent from gas and 13 percent was nuclear electricity.

Deutsche Bahn decided in late 2017 to halve its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, compared to 2006, and to be climate-neutral by 2050. Subsidiary DB Schenker was the first international logistics company to aim for growth in the next decade without boosting emissions. According to carbon disclosure project CDP, Deutsche Bahn is already one of the globe’s two most climate-friendly rail operators.

For many years, environmental organisations have called for better use of Germany’s railways – but so far, to little effect. Rail freight traffic actually decreased by three percent between 2011 and 2016.

Many transport experts now see a real opportunity for change, because specific transport climate targets have increased the pressure to act, and digitalisation appears to offer new solutions.

The transport ministry presented a “Masterplan for rail freight transport” in 2017 to increase freight transport by train. It promises 350 million euros to lower prices, and further infrastructure investments, including digitalisation and automation, in order to increase the network’s capacities, lower costs and boost efficiency.

This is particularly relevant because today’s just-in-time production processes require ever smaller payloads, whereas traditionally, rail transport excelled at carrying large loads over long distances.

“One reason why more freight traffic hasn’t shifted from roads to rails, despite decades-long calls for action, is the uneven cost burden,” says Agora Verkehrswende, referring to higher rail fees and taxes compared to diesel.

The present government’s coalition agreement promises to electrify 70 percent of the network by 2025 and further measures to boost rail transport.

In order to cut emissions on less-frequented train lines that are not electrified, Germany plans to use world’s first hydrogen fuel cell passenger trains by 2021, replacing diesel engines – a concept that could be used for freight trains in the future.

Shipping and aviation last in line

Clean-up efforts in freight have so far almost entirely sidestepped shipping and aviation, because neither can use battery-powered systems, due to weight and range issues similar to those hampering the electrification of heavy duty trucks.

Deutsche Post DHL also faces this problem in air freight. The group says it supports alternative aviation fuels, but adds that “at present not enough is known about how these fuels impact air operations and the environment, ruling out their large-scale deployment.”

According to the BDI, synthetic fuels are the only option for carbon-neutral shipping and aviation. Smaller planes can use hybrid-electric engines with batteries or fuel cells, but these are not suitable for larger planes in the foreseeable future. [For details, read the interview Emission-free aviation is technically feasible - DLR Researcher]

Many transport experts say that only an overhaul of taxes and fees to make fossil fuels much more expensive will provide the incentive to clean up ships and planes. But such a measure is currently not on the government’s agenda.

“We’re not going to see real progress reducing emissions in either air transport or shipping,” says Michael Cramer, an EU parliamentarian with the German Greens, “until the tax advantages they have – and rail doesn’t have – are removed. Currently, the dirtiest fuels are being rewarded.”

Thus, many obstacles remain on the road to a climate-neutral freight transport system. The necessary technologies are becoming available, but their large-scale roll-out will depend on the right policies.

“It’s technically feasible to decarbonize Germany’s domestic transport sector by 2050,” says Martyn Douglas, German Environment Agency (UBA). “But it’s difficult to say it’s realistic. It’s good though just to have goals that can be worked toward.”

*Like Agora Energiewende and the Clean Energy Wire, Agora Verkehrswende is funded by the Stiftung Mercator and the European Climate Foundation.