Sustainable finance principles could have reduced EU's energy dependence on Russia - finance expert

The year 2022 in European and German climate policy started with a heated debate on whether to include nuclear power and gas in the EU’s new taxonomy for sustainable finance. What exactly is this taxonomy to begin with?

The taxonomy has been conceived to create transparency about what exactly defines sustainable economic activities and related financial operations. It is a reference framework that allows investors to gauge the environmental impact and other aspects of a given financial product’s underlying assets, for example the equities, meaning “companies,” in an equity fund. If it is applied correctly, it allows to avoid greenwashing at a large scale

How did the need for having such a reference framework arise? Did it start out as a political decision to regulate businesses or as a market-based tool for investors?

The rapid development of so-called “green” financial products, such as green bonds, in recent years triggered the need for a commonly accepted definition of what exactly justifies such a label. This is a key aspect for investors, who want to minimise sustainability risks and avoid being accused of greenwashing. What the taxonomy certainly does not do is prohibit investments in certain technologies - it only provides definitions. Investors can choose whether and how to apply it.

Apart from the need for disclosure and transparency, which is driven by a market logic of reducing information asymmetries and transaction costs, the early approaches toward sustainable finance were strongly motivated by moral considerations - also known as the “inside-out perspective” - that question the impact of an investment on the rest of the world. Championed initially by smaller financial institutions like church-owned banks, which wanted to terminate investments in countries that, for example, violate human rights, this was all about defining exclusion criteria and thereby ruling out particularly harmful activities from the investment “portfolios.” And once you start defining the negative aspects, you might as well start defining the desirable aspects. In essence, the taxonomy is a project driven by investors rather than by regulators.

So, the idea originated from a political and ethical logic and a business logic has emerged from that?

In a way, yes. A concept that illustrates this conjunction is known as ‘double materiality.’ First, following what you call a “business logic,” you need to identify which “sustainability issues,” such as increases in extreme weather events or the dependence of your investee companies on endangered ecosystem services, affect your financial returns. We call this the “outside-in perspective,“ where the “environment” has an impact on your business or, by extension, your portfolio. Then you add your “ethical logic,” which is relevant for those investors that also care about the sustainability of returns. Regulation ultimately combines these two aspects: environmental regulation penalising or constraining the impact of a company’s or a bank’s portfolio on, say, water pollution combined with disclosure regulation obliging a company to report about its impacts turns the inside-out “ethical logic” into an outside-in “business logic.”

Funding for Future: How sustainable finance reshapes climate action – and why journalists should listen more closely

Could you give an example of what this means in practice?

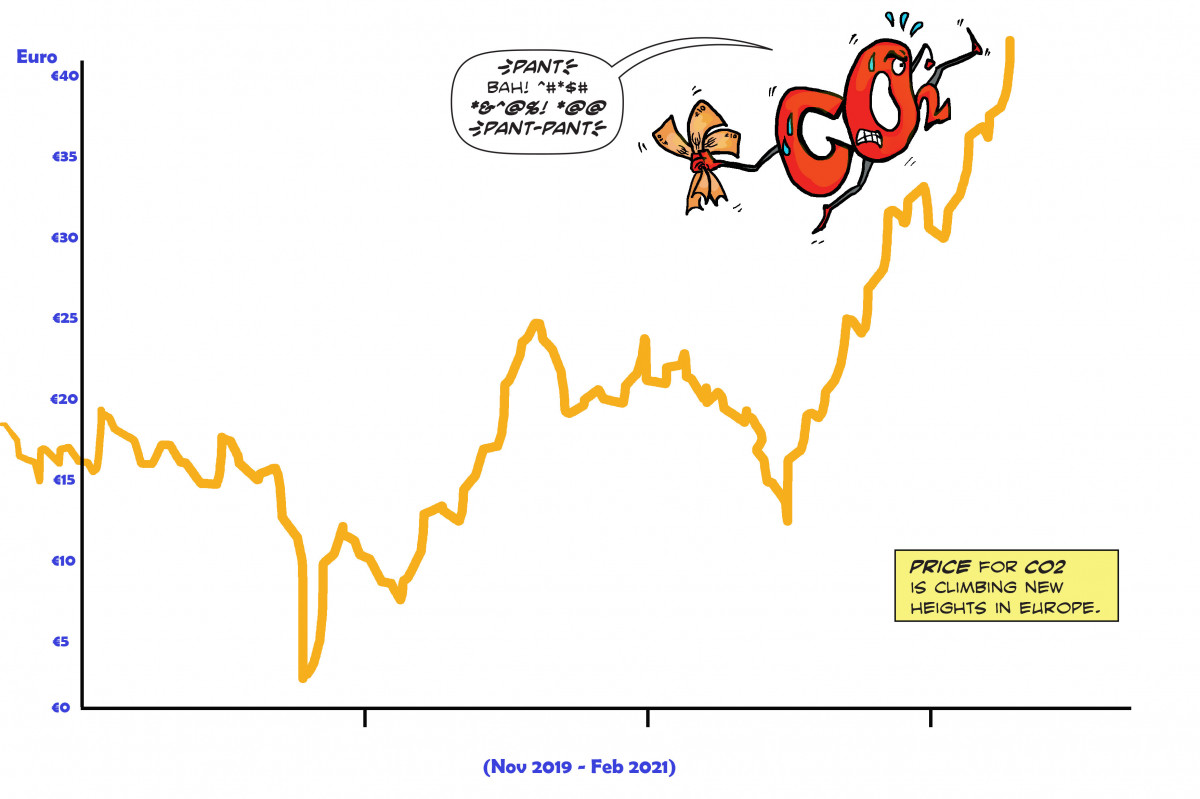

The most prominent examples in terms of climate are certainly the 2015 Paris Agreement and the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). “Paris” put climate on top of everybody’s agenda, and the parallel reform of the ETS has triggered rising allowance prices. The combination of these two events quickly showed that companies with high emissions face a serious carbon cost challenge. This was demonstrably the case already before 2015, but the trends became clearer after the landmark Paris agreement and when carbon-intensive companies started to lose market value - in particular those facing the carbon price increase under the EU ETS. This example works for CO2, but it also makes clear that a commonly accepted reference system allowing companies and investors to synchronise their understanding of all key dimensions of sustainability is needed by both financial and non-financial companies to speak a common language when it comes to material issues.

But if a strategic shift to stronger sustainability is already triggered by market forces and political decisions like the Paris Agreement or the ETS reform, why would the inclusion of nuclear and gas tarnish the taxonomy’s effectiveness?

The whole idea behind the taxonomy is to simplify and streamline things and not to provide detailed guidance for every kind of technology in the book. Again, it is not meant to prohibit investments in any project and there may be, in a particular local or national context, desirable “bridge technologies” that can facilitate emissions reduction even though this means investing in fossil fuels, for example replacing oil and coal heating with more efficient gas. But if the aim is to provide a clear-cut, science-based reference framework that defines what can be considered sustainable, it should be limited to the activities that are actually sustainable - which raises questions regarding nuclear waste. And it should draw on scientific standards and on authoritative sources like the International Energy Agency (IEA), which clearly excludes gas from its “net zero by 2050” scenario. If there is a business case for a gas or nuclear power project, it can still go ahead unhampered – if there is one, that is.

Why then would certain member states advocate so eagerly for the inclusion of certain technologies?

Things become more complicated if you look at state aid in situations where investments are mainly politically motivated – think of the “nuclear renaissance” in France. Inclusion in the taxonomy would thus greenlight these state activities under the label of sustainability. And it would send a message to our partner countries that any state can ultimately pick activities it considers beneficial to its own economy, call them sustainable and include them in their own “green” taxonomy. This would mean that the EU taxonomy would fail in its ambition to become a “gold standard” in the field.

But not only might other countries see this as invitation to treat anything they want as sustainable: citizens in the EU might also become sceptical about their small and individual contributions to saving the planet if the EU says nuclear power is sustainable despite its many unresolved environmental challenges.

Do you think there’s any chance that the taxonomy will ultimately exclude nuclear power and gas, given the chorus of critics, including the EU’s own sustainable finance expert panel?

I don’t think the final word has been spoken on this issue. The European Commission most likely did not anticipate the outcry over its decision coming from almost all corners, including the vast majority of financial institutions. These controversial technical questions about gas and nuclear are regulated via a separate so-called delegated act, which means that the European Parliament still has a chance to let the process grind to a halt, even though the remainder of the taxonomy may remain untouched. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could tip the balance regarding gas here and many are now, rightly, calling for the Commission to pull the plug, which it can do and for which there are clear legal precedents.

Another relevant development is the idea to extend the taxonomy to also define “low environmental impact” and “significantly harmful” activities. So far, we’ve focused on a green taxonomy that defines sustainable activities. Our subgroup in the EU Sustainable Finance Platform has now submitted a report to the Commission proposing these extensions.

Wouldn’t adding more categories make things more complicated again?

Admittedly, yes, there’s a risk this could happen. But this could be kept to a lean standard and help avoid a political gridlock on individual issues. It serves as a “pressure valve” for the green taxonomy and offers a hand to the companies concerned: 'You are not green? No problem, here’s how you can show that either your environmental impact is low or how you credibly transition out of harmful activities.’

Expanding the scope of the taxonomy could be particularly helpful to smaller companies with little expertise in the field. They could assess and show to their bank where they stand, that they may be “mostly harmless” or how they plan to adapt their business strategies accordingly. But the “transition” category is not a carte blanche. There need to be clear metrics and timescales that chart the path for a transition for every company willing to do it. And at the end of the day, some “significantly harmful” business models would simply no longer fit into the picture.

Energy trading and fossil fuels are also key aspects of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, raising questions not only about the cost of energy supplies but also about investments in defence capabilities and the military, which also are a crucial part of the ESG (environmental, social, governance) criteria that lie at the heart of sustainable finance activities. Can the taxonomy debate continue without factoring in the impact of Russia’s invasion?

There will, of course, be an impact, as the taxonomy essentially represents goals that society has agreed on. The idea of sustainability itself is based on the commonly accepted norm that there’s a responsibility to future generations to leave them a functioning environment. You could not justify climate action if your only focus was rapid profit maximisation and economic growth. This does not mean that arms producers suddenly become classified as sustainable, but it can influence the aims society considers desirable and open a debate about which products arms producers sell exactly and to whom.

But bringing a more systematic approach to energy investments and a strategy for the transition could also help prevent dangerous dependencies like the one the EU and especially Germany find themselves in now with respect to energy imports from Russia. Germany has almost inexplicably hesitated for years to turn away from Russian gas even though Russia already launched an attack on Ukraine in 2014 and occupied the Crimean peninsula. A clear timeframe for using gas as a transitional technology with an end date outlined in a taxonomy might have helped speed up the inevitable turnaround we see now. Setting an end date is what defines a so-called ‘bridge technology.’

Chancellor Olaf Scholz used to be finance minister in the previous government and it was under his aegis that Germany declared its ambition to become a global leader in sustainable finance. Before that is achieved - what could his new government coalition do to at least help the EU taxonomy live up to the expectations?

The government could clarify its position on gas as a ‘bridge technology’ and set an example for how to define it by presenting a clear plan on how long it is supposed to help out and how it fits into the broader picture of climate neutrality – so, effectively a phase-out roadmap. Renouncing gas entirely in the next years never has been a majority position among sustainable finance experts but outlining how it will help climate action has.

Given the impact that a broad application of sustainable finance criteria would have not only on climate policy but also on companies and individual citizens looking to invest their savings, do you think that the topic is communicated well and is adequately covered in the media?

Covering sustainable finance certainly is somewhat unrewarding from a journalistic perspective. It is very technical and laden with misunderstandings, such as the taxonomy being a list of do’s and don’ts that curtails investor freedom. Consequently, media coverage has often been meagre in recent years. And perhaps technical experts should make themselves heard more. The Sustainable Finance Research Platform (WPSF) aims to achieve exactly that and to encourage journalists and media representatives to apply a more holistic view that they could then use to get the key idea across to the broader public. A joint effort against misunderstandings or in some cases even misinformation that aims to establish a better foundation for debate would probably be appropriate.