EU reliant on next German government’s climate resolve to uphold Green Deal’s promises

Amid the onslaught against climate action set in motion by the new US administration, the question whether a new German government will defend the landmark European Green Deal has become critical for the EU’s ambition to remain a global leader in progressive climate action. Germany, alongside Europe, has seen its certainty on security, trade, and diplomacy in the transatlantic relationship evaporate overnight, as Donald Trump assumed the role as US president for the second time. Yet the EU’s largest economy has been too preoccupied forging a new government to show real leadership on the global stage, after the last coalition collapsed on the very day that US voters elected Trump back to the White House.

While fellow EU states are waiting for conservative chancellor candidate Friedrich Merz’s CDU/CSU alliance to finally sign off a coalition deal with the Social Democrats (SPD) of outgoing chancellor Olaf Scholz, the new geopolitical realities presented by the Trump administration are already forcing Germany to rethink its role in Europe. With the US withdrawing from its role as the underwriter of global free trade and European security, this includes Berlin’s willingness to finance joint EU initiatives and deepen the internal market through initiatives like a capital market union or an energy union. It also changes the role that its industrial and energy policy play, as European sovereignty on defence, energy, and nuclear deterrence become key talking points.

European partners are therefore hoping for a chancellor Merz who fully grasps the scale of the task at hand and focusses on building alliances in the EU and beyond based on joint strategic priorities that are implemented with consistency.

“Germany is back,” Merz sought to reassure his country’s allies in April, signalling that the conservative leader who started his political career in the European Parliament in 1989 grasped the urgency of the moment and the need for a unified European response to protect Germany’s national interests. One of his first moves after the election included pushing an unprecedented spending package through parliament. The special fund worth hundreds of billions of euros and reforms to the country’s debt brake led to hopes among European peers that it might swap Germany’s traditional fiscal cautiousness for more generous economic stimulus policies.

EU has tied future economic success to climate ambitions

Under Scholz’s three-party coalition, European partners too often sorely missed a clear message from the German chancellery, Sophie Pornschlegel of think-tank Europe Jacques Delors told Clean Energy Wire. “There’s definitely a sense of optimism, almost euphoria even, that the new government will be more decisive on European matters than Scholz was,” Pornschlegel said. However, “this doesn’t mean that Berlin should call the shots alone, but rather take the initiative in unifying positions among EU partners.”

Most importantly, the next German chancellor must avoid acting on a ‘Germany first’ platform and ensure that Europe will benefit along the way through some sort of “trickle down” effect, Pornschlegel said. “There’s a great interest in Europe that Germany takes greater leadership and acts decisively in central policy areas,” she argued, adding that “we now need a European answer first – and that ultimately will also benefit Germany.” This would include coherent initiatives on industry competitiveness, strengthening the EU’s budget, and managing decarbonisation, she argued.

The Merz government’s proposed coalition treaty has largely held course on central climate and energy policies, even if the parties emphasised economic competitiveness over climate action, especially in comparison to the previous coalition. For Kurt Vandenberghe, who leads the EU Commission’s department on climate action, there are few alternatives for Europe but to stick to the Green Deal’s basic tenets if it is serious in its bid to reinvigorate the continent’s industry.

The deal that was approved in 2020 sketches a path towards EU climate neutrality by 2050 and aims to decouple economic growth from resource use. “The climate agenda is an agenda for modernising the economy and preparing it for a future that is warmer, less secure and globally more competitive,” Vandenberghe told journalists in March in Brussels. By this logic, the chancellor-in-waiting, who has made economic recovery the bench mark of his government’s success, should strive for consistency with the country’s national energy transition as well as with the Green Deal.

Competitiveness in Europe would be “impossible” to achieve in the future if the bloc’s energy system remained centred around fossil fuel-based technologies, Vandenberghe argued. For the Commission’s chief climate bureaucrat, the Green Deal therefore is “a shock therapy that we’ve delayed for too long.” Throughout all the consecutive crises Europe has dealt with since 2019, “no change in government has led to a fundamental questioning of climate targets.”

The fact that climate policy provides a binding framework for the next 25 years for the sake of a shared European goal would act as an advantage, Vandenberghe added. “Access to and availability of green investments is more secure in Europe than in the US, posing a comparative advantage for us,” he added. As the Trump administration in the US seemed bent on splitting the world “into countries who want to keep fossil fuels and those who want to electrify,” Europe had “no choice but to pick the latter side.”

Appetite for ambitious emission reductions has waned across Europe

But despite new record shares of renewable power output and continuous emissions cuts, the appetite for ambitious climate policy has waned across Europe between the ‘climate election’ in 2019 and the following ‘tractor election’ in 2024. As climate action slid down on the list of priorities for many governments in favour of bolstering industry and competitiveness, the second Commission under Merz’s fellow CDU member Ursula von der Leyen presented its ‘omnibus package’, which throttled climate action and sustainability ambitions under the guise of cutting bureaucracy and streamlining policies. Moreover, EU climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra delayed the presentation of the bloc’s 2040 climate target, giving the next German government time to present its own position to the proposed 90-percent emission reduction target. The initial signals coming from Merz's government suggest that it will consent to the target, but only with the so far unprecedented caveat of being allowed to offset emissions outside of Europe.

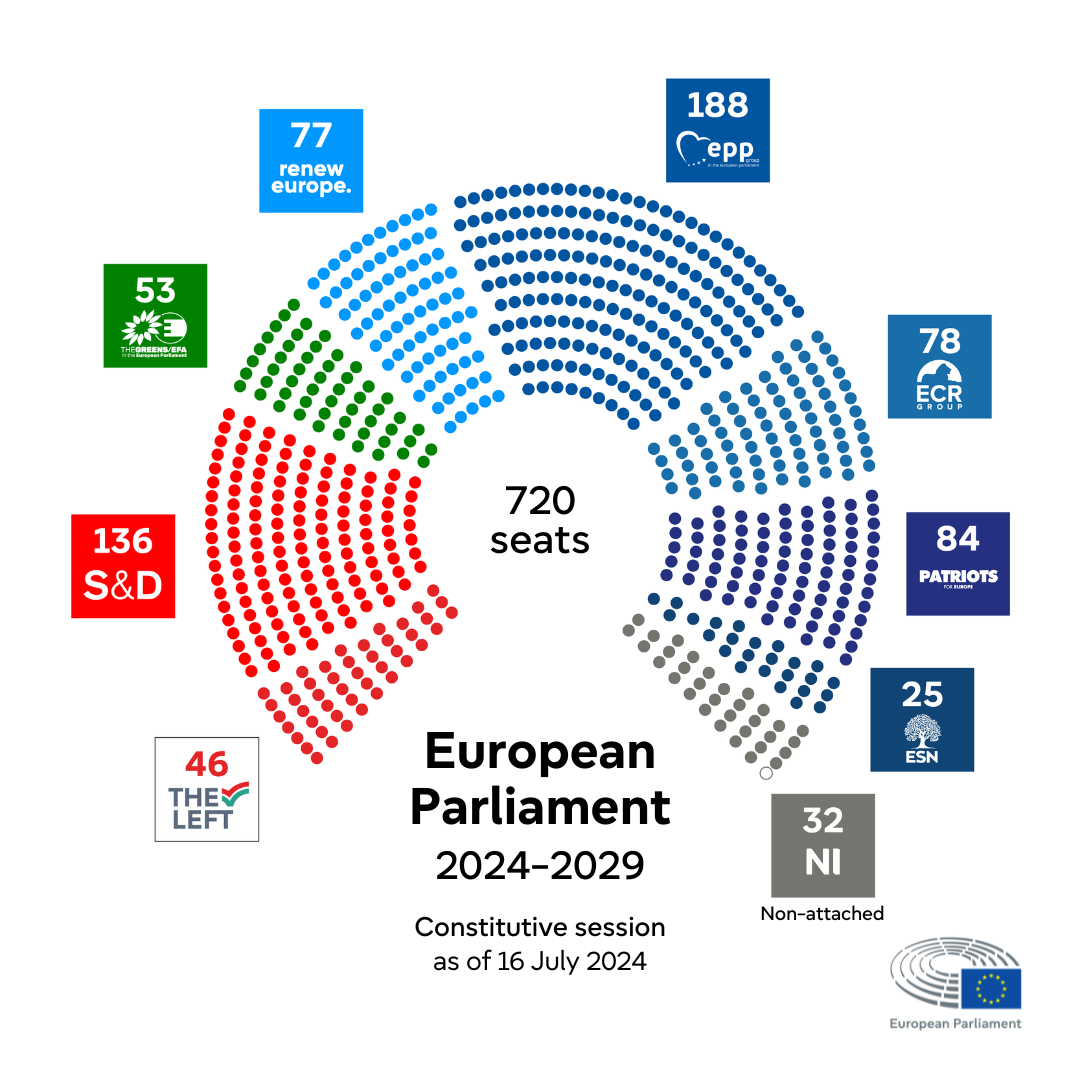

The sense urgency of committing to decarbonisation measures also has ebbed in the European Parliament. In 2019, Europe’s directly elected representatives declared a climate emergency and urged the Commission to align all policy with the UN’s target of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Six years on, and with some researchers believing the UN target has already moved out of reach, the EU Parliament has changed its composition and stance. And its biggest faction, the European Peoples’ Party (EPP), of which Merz’s CDU/CSU is the biggest member, is spearheading the newfound restraint on climate ambition. “The Green Deal really is under attack in the new parliament,” according to Green Party MEP Michael Bloss. “This is unfortunate since it provides a pathway on a wide range of sectors that are designed in conjunction,” he argued. For example, lower CO2 reduction targets for cars - a constant battleground for consecutive German governments - would translate into higher CO2 prices, Bloss explained. “This is much more difficult to communicate to citizens.”

“Creating more insecurity by scrapping parts of the Green Deal must be avoided,” the Green MEP warned, adding that the EPP's repeated flirtation with parties further to the right in the EU Parliament could set dangerous precedents for climate policy. “Maybe the current changes to the security architecture will push the EPP further into pro-European territory,” he added.

Merz at risk of coalition infighting and far-right pressure

For EU think tank fellow Pornschlegel, Merz’s general approach to climate policy puts Germany more in line with the European mainstream again, compared to the previous government. “Constraints posed by the Green Deal increasingly are seen as a nuisance,” she said. The challenge for the next German government would be to make clear that “decarbonisation, energy security, and economic competitiveness really are interlinked and need to be treated as such.” Opening the door to gutting regulation through initiatives like the omnibus law therefore went in the wrong direction and jeopardised the coherence of European climate policy, Pornschlegel argued.

However, it is unclear how much leadership Merz will be able to muster on this task. Like outgoing chancellor Scholz, whose coalition collapsed over quarrels about climate and transformation funding, Merz is not immune to the internal spats and pitfalls of coalition governments. Initial discrepancies in the conservative camp, for example regarding cooperation with the Green Party between senior CDU politicians and assertive Bavarian state premier Markus Söder, leader of the CDU’s sister party Christian Social Union (CSU), or with the SPD regarding cooperation with the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), give a flavour of stress tests the aspiring coalition might face.

The conservatives’ flip-flopping on Germany’s nuclear exit (which the CDU/CSU insisted on reversing before dropping the demand in the coalition treaty), the EU’s planned 2035 ban on new combustion engine cars (which the SPD supports but the conservatives vehemently oppose) or the planned expansion of the EU’s emissions trading system (ETS2) on transport and heating in 2027 are examples for potential energy and climate policy stumbling blocks – and could further open a flank for attacks on the social impact of climate policy by Merz’s political opponents.

While even the previous government with the Green Party delayed increases to carbon pricing over fears of a popular backlash, the new chancellor-in-waiting has said carbon pricing under the ETS should become the central pillar of decarbonisation efforts. But the 2018 ‘yellow vest’ protests in France in response to a similar surcharge on fuel prices still reverberate in Brussels as a reminder of the potential for disruption, and for exploitation by various actors, of climate policy. Polling successes by the AfD and a rejection of conservative voters of what is seen as excessive concessions made by the conservatives to the centre-left SPD on the national debt brake add further pressure on Merz and could see climate action become a priority for the opposition rather than for the government.

Moreover, the major spending package’s stimulus effects could be slowed down by sluggish bureaucratic decision-making chains, the intricacies of the federal system, and practical issues in ensuring that money is disbursed and materials and workers are in place for implementation – while Trump’s tariff turmoil adds further woes to economic recovery prospects. To keep course on core decarbonisation and industrial recovery components linked to the Green Deal, Merz would have to focus on close coordination with Germany’s largest neighbours, France and Poland, Pornschlegel said. “If the goal is to support Europe as a whole, it must be decided at the EU level.”

Merz’s arrival had sparked hopes for closer alignment particularly in France, as a revival of the ‘Franco-German engine’ as an axis for EU progress proved difficult during Scholz’s tenure, not least due to engrained differences over the right approach to energy policy. The aspiring German chancellor’s early announcements to seek close alignment with Warsaw and Paris as well as budding plans for a renewed Franco-German push to harmonise European energy policy could be seen as a sign that Merz is willing to take on the new role Europe needs Germany to play.