German govt’s climate policy has been through baptism of fire in first 100 days

The tradition in German media to give a first assessment of a newly formed government after 100 days in office is usually a rather relaxed exercise. Ministers receive some early marks for their performance and the first surveys asking about citizens’ feeling towards the administration they just voted in give a hint whether the government is seen as swiftly delivering on its election promises or not. For Germany’s so-called ‘traffic light coalition’ under Chancellor Olaf Scholz, however, this initial stage turned out to be far less gentle than expected.

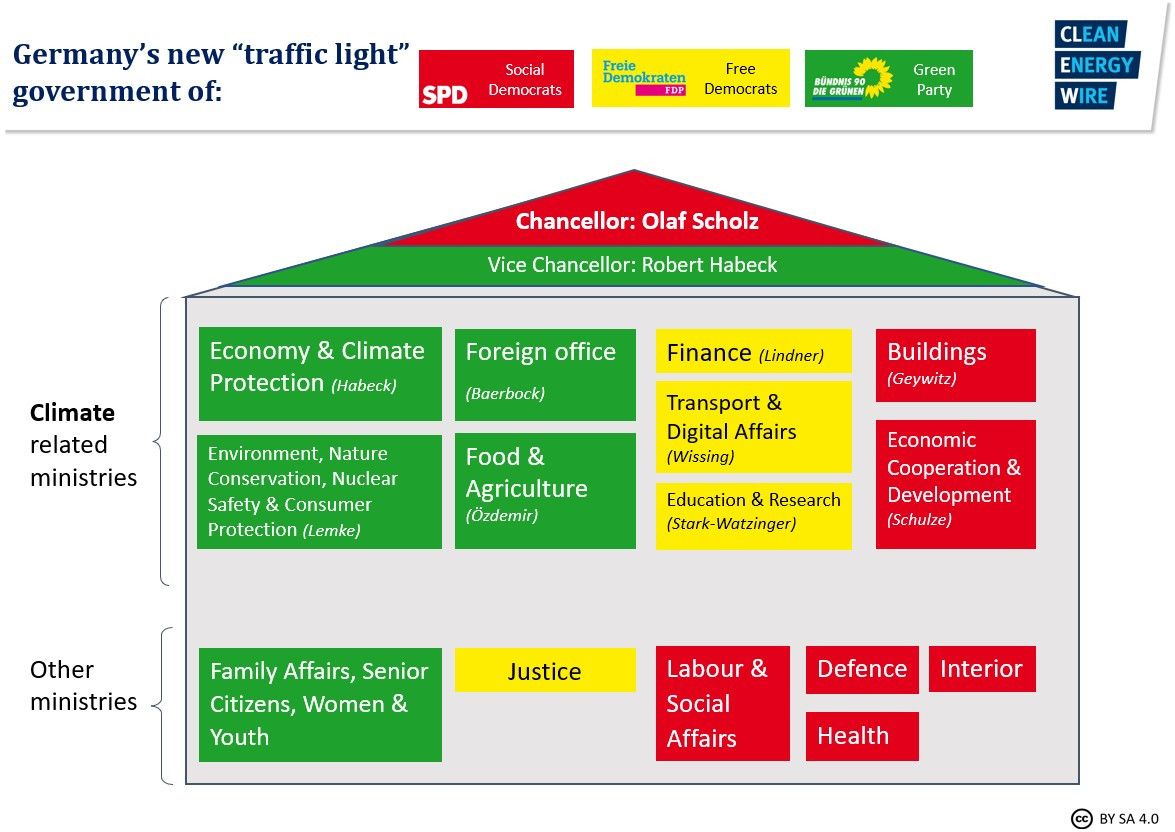

Since the government of Scholz’s Social Democrats (SPD), the Green Party and the Free Democrats (FDP) was sworn in, the surrounding conditions for the fledgling three-party coalition changed at breath-taking pace. Ending 16 years of conservative rule under Angela Merkel’s CDU, the new and more left-leaning government set out with a clear focus on more ambitious climate action and a fast transition to a climate neutral economy, offering a sense of a fresh start after almost two years of a crippling pandemic. Inaugurating the new cabinet on 8 December last year, the country’s president, Frank Walter Steinmeier, called the new coalition's ambition a project of “immense proportions”. If anything, developments in its first three months in office have only further inflated the size of this task.

The rise of energy prices that started in the second half of 2021 turned out to not disappear quickly and instead kept gathering pace, fuelling one of the fastest inflation rates the country has had to deal with in decades. Likewise, supply chain challenges continued to linger, posing severe production difficulties for many industrial companies and stalling investments in decarbonisation. And the coronavirus pandemic, thought to be receding just ahead of the new government’s start, returned with unprecedented vigour in the form of the omicron variant. Most importantly, however, Russian President Vladimir Putin opted to wage all-out war on Ukraine, simultaneously causing immense human suffering and upending decades of German and European energy and security policy certainties.

This dramatic turn of events compelled the government to review some of its key election promises practically overnight. Economy and climate minister Robert Habeck from the Green Party had to break it to his climate-concerned voters that energy supply security ultimately trumps emissions reduction, announcing that the country could not continue to shutter its coal-fired power plants at the desired speed to gain some wiggle room in light of a looming halt to Russian energy supplies. In a move hardly imaginable just weeks before, the director of Germany’s prestigious Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), Ottmar Edenhofer, gave his blessing to a re-evaluation of the country’s coal exit timeline, arguing that phase-out deadlines would not have to be followed “slavishly” given the new circumstances.

This gives an indication of the magnitude of change the new “super minister” Habeck, who had vowed to reconcile climate action with prosperity, has had to face since his inauguration. To the relief of many Green supporters, Habeck’s ministry at least held firm on the country’s plan to end nuclear power at the end of the year, even though surveys suggest many people in the country have softened their views regarding the phase-out’s timing. For Habeck, an even more rigid and determined turn to renewables and green hydrogen offers the only long-term solution available.

Treasury channelling funds into special-purpose budgets to tackle climate crisis and war

Meanwhile, finance minister Christian Lindner from the pro-business FDP, who ran on a platform of limited public debt and economic liberalism, had to look for ways to make available hundreds of billions of euros for both propping up Germany’s notoriously underfunded military and a financial booster to the energy transition. His approach to channel funds into separate special-purpose budgets allowed him to bypass a violation of the country’s so-called debt brake on the budget but might still put the treasury in hot water, as opposition parties and the government’s auditors both voiced doubts about the move’s constitutionality. The 2022 budget already had to be supplemented by new debt worth nearly 100 billion euros even before the economic effects of fast-rising energy prices and repercussions of sanctions on Russia. The treasury’s draft planned with a “core budget” of about 457 billion euros but said the final required sum would be impossible to calculate at present. It also doesn’t include 100 billion euros Chancellor Scholz announced for the military, which will be counted in a special fund outside the budget.

Amid the mixture of actual shortages and speculation driving rising prices, many energy-intensive companies have already voiced fears of severe production cuts and dwindling profits. Similarly, rising costs for heating and petrol have led to worries that poorer households could end up footing much of the burden, which could compel the government to open its pockets even more – even though a sudden halt to a building refurbishment programme in January by the economy ministry had already shown the government to be seriously looking for ways to keep costs in check. A proposal by Lindner to help out motorists with a sweeping rebate on petrol was met with resistance, arguing it would allocate precious funds to prevent people from reducing fossil fuel consumption while disproportionately favouring the well-off, who tend to use their cars more intensively. Illustrating the differing conclusions that government parties are drawing from the price crisis, economy minister Habeck instead backed calls by environmental groups, who called for imposing speed limits that automatically reduce fuel consumption and thus costs and emissions.

From a budget perspective, however, the government would still be able to respond effectively, Kristina van Deuverden, public finance expert at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), told Clean Energy Wire. The end of Germany’s renewable power levy could be the first step in that direction. “High power prices currently make funds available that otherwise would have been used to remunerate renewable power operators," van Deuverden said. While Lindner’s announcement to prop up climate investments would not mean as much of a boost as the minister suggested, it could still lead to more stringent decarbonisation funding. "The 200 billion euros for climate action spending announced by finance minister Lindner do not include any additional funding – but they perhaps attribute more clearly where existing funds should go over the next five years, so 40 billion euros earmarked per year.”

While it could be argued that coming to terms with the reality of governance for the Greens and the FDP is the fate of parties previously commenting from the opposition ranks, Chancellor Scholz’ Social Democrats, who were part of the government in varying coalitions for the better part of the past 25 years, perhaps had to face the greatest reckoning after their fulminant comeback in last year’s election. The suspension of the controversial Nord Stream 2 pipeline pulled the plug on a project that many in the SPD had rallied behind in recent years despite widespread criticism, both at home and by Germany’s neighbours. The approach of integrating Russia through trade and keeping geopolitical tensions in check by being a loyal customer for years had secured the country comfortable access to Russia’s vast resources – but ultimately turned into an immense liability when Russia’s president let the façade of amicable cooperation implode.

"Natural gas as a bridge has collapsed"

A key energy transition premise of consecutive German governments to treat natural gas as a “bridge technology” that would allow for a smooth phase-out of nuclear and coal power vanished with Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, as the hastily announced construction of two new LNG terminals will not compensate for the rupture with the biggest fossil fuel supplier. Germany’s belief in natural gas as a perfect medium-term fix used to be so firm that it pushed for an inclusion of the technology in the EU’s taxonomy on sustainable finance at the beginning of the year. Even the Greens could not halt the hunger for gas, seeking to assuage voters that the bridge would eventually lead to gas infrastructure ready for green hydrogen. “The bridge has collapsed,” said Patrick Graichen, state secretary in the economy and climate ministry, summing up the new government’s predicament the same day he had to announce that the country’s greenhouse gas emissions had bounced back by 4.5 percent in 2021 after the slump caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

Despite these challenges, Chancellor Scholz seems to have arrived in his position as the country’s new leader, with his rigorous response to the Ukraine war lifting his ratings up ten percentage points to 73 after his first 100 days in office. Also Green foreign minister Annalena Baerbock, whose bid to initiate a new phase in German diplomacy based on climate action was confounded by the outbreak of war in eastern Europe, was able to consolidate her reputation and led the ranking of most popular ministers after the first three months.

47% of Germans consider new government as a "true fresh start" for the country

Her cabinet colleague Volker Wissing (FDP), who leads the transport ministry crucial for the energy transition, did not score quite as favourable among voters but still managed to surprise observers with his decision to let go off his party’s insistence on keeping a door open for combustion engine cars. Ending years of resistance by Germany against fast progress in car emission limits, the government signalled it would not stand in the way of ending new registrations Europe-wide by 2035. Alas, the war in Ukraine could still pose difficulties for a fast transition to e-cars, as dependence on Russia for the car industry is also strong for non-fossil resources needed for battery production.

The overall impression on voters the government has left in its first 100 days is clearly a progressive one, with 47 percent saying the traffic light parties represent a true fresh start for the country, according to a survey by the Allensbach Institute. However, it also showed more than half of respondents feared progressive climate policies aggravate social injustices in the country and nearly half believe they will be worse off individually. The traffic light coalition’s vision that more effective climate action would increase prosperity was only shared by seven percent. Dominick Schwickert of think tank Progressives Zentrum, which commissioned the survey, said the results chimed with direct interviews conducted in poorer regions of the country, urging the coalition parties not to overlook the results. “The new government will only be able to keep up support for rigorous climate action if it addresses the question of social justice.”