Q&A: EU sustainable finance taxonomy and the dispute about nuclear power and gas

Contents

- What is the EU taxonomy and how is it linked to sustainable finance and climate action?

- What are green activities under the taxonomy?

- What will the taxonomy mean for governments, financial actors, businesses and citizens?

- When will the taxonomy start to apply?

- Which parts cause disagreement?

- Why the dispute about nuclear and gas?

- Will the taxonomy fulfil its aim if nuclear and gas are included as planned?

- What happens next? What are the chances that nuclear and gas will be included?

1. What is the EU taxonomy and how is it linked to sustainable finance and climate action?

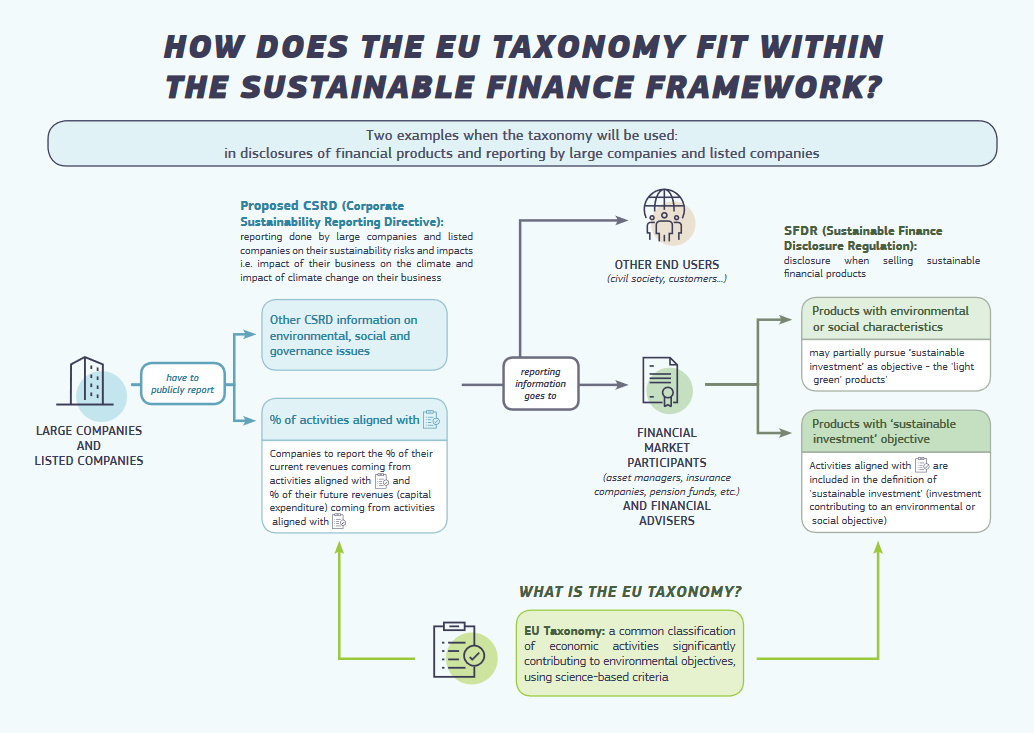

The EU taxonomy is the centrepiece of a broader sustainable finance package that aims to better align the financial system with environmental, social and governmental (ESG) goals in policymaking. It is a classification scheme that establishes a hierarchy for investments according to their effect on the ESG goals. It is meant to serve as a “common language” for banks, insurances, businesses, governments and other investors to gauge the – positive or negative – sustainability impact of economic activities along widely accepted criteria.

Ideally, this could increase transparency to allow better risk assessment by investors, avoid greenwashing and leverage efforts to decouple economic growth from environmental pollution in the context of the EU Green Deal, the European Commission says. The classification scheme partly entered into force at the start of 2022, with controversial questions in the energy sector still being debated. The fields already covered by the taxonomy have been listed in a comprehensive “taxonomy compass” provided by the Commission.

Researchers at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) initially said the taxonomy could become a “breakthrough” that sets global standards for classifying sustainable investments.

2. What are green activities under the taxonomy?

The taxonomy’s basic premise for sustainable investments is that these must serve at least one of six overarching environmental goals and not contradict (“Do No Significant Harm”) any of them. These goals are emissions reduction, climate adaptation, sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, establishing a circular economy, reducing environmental pollution and protecting biodiversity.

The scheme only covers sectors of the economy in which sustainable investments can be made in the sense of an ecological transformation. This excludes sectors that can be replaced by other technologies, such as coal-fired power production. Instead, it is focused on indispensable technologies and sectors where investments can reduce the environmental impact, for example steel production.

3. What will the taxonomy mean for governments, financial actors, businesses and citizens?

The taxonomy’s impact is tied to the effects of the entire EU sustainable finance package, which also includes comprehensive reporting obligations for companies and the financial sector. Ultimately, it holds implications for energy and many other sectors of the economy that will affect every actor on financial markets, from large investment funds to small savers and pensioners relying on market returns.

Already since 2021, financial service providers can no longer simply claim that a product is sustainable but must make clear which criteria they apply. Since 2022, they are obliged to disclose data about the environmental aspects of their assets that are part of the taxonomy. Producers of goods like cement or steel that seek an investment credit from a bank or insurance covers for a new project, for example, will need to demonstrate that their products meet criteria like greenhouse gas emissions caps per unit, based on the performance of the most efficient technologies available in a given EU industry. These criteria are tightened over time as the efficiency frontier is expected to shift further. Individual investment projects also will have to undergo a mandatory environmental compatibility assessment.

Businesses have to indicate how many of their activities are covered by the taxonomy. At a later stage, they must indicate whether or not their activities are a sustainable, based on strictly financial metrics like turnover, investments or operating expenses. And financial reporting duties for companies are set to further intensify: according to the EU's Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, even smaller capital market-oriented companies will have to present corresponding indicators in much greater detail than before by 2024. The German Council for Sustainable Development (RNE) said the number of affected companies would climb from about 600 to 15,000, adding that many still lacked the qualification and personnel to comply.

And also the public sector will be affected: German state development bank KfW said that it promotes climate-friendly activities based on the EU taxonomy. And public funds will probably also flow according to taxonomy criteria. This is because municipal utilities, which are owned by local authorities, are often responsible for investing in power plants.

4. When will the taxonomy start to apply?

The general framework of the taxonomy – the EU’s Taxonomy Regulation – entered into force in mid-2020, but important details were left unresolved. The Commission adopted a first act with implementation rules only one year later. It defines activities that contribute substantially to climate change mitigation and adaptation and includes renewables like solar PV and wind turbines (the Commission decided to leave out the controversial issue of nuclear and gas at that point). The act cleared all legislative hurdles and has applied since 1 January 2022. Mandatory reporting for certain financial entities and companies has thus started.

A complementary delegated act on nuclear and gas activities would enter into force and apply once the scrutiny period is over and neither the member states nor the parliament object.

5. Which parts cause disagreement?

A row over the sustainability of nuclear power and natural gas has emerged as the most controversial question the taxonomy has opened so far. The current goal of making the EU climate neutral by 2050 will require large-scale investments in every sector of all European economies, both in the form of state funding and of private investments. In order to make long-term lending and investment decisions that contribute to the goal of climate neutrality, the financial sector needs clear guidelines on which activities count as sustainable. The European Commission presented a delegated act that grants a sustainability label to both technologies if they meet additional criteria, such as a waste management concept for nuclear power and CO2 reduction plans for gas facilities.

6. Why the dispute about nuclear and gas?

Each member state of the European Union determines its own energy mix. That is true for today’s mix, but the questions of how to fuel a climate-neutral economy and which sources to use during the transitional period to get there are answered differently across Europe as well. For some countries, such as France or Finland, nuclear energy is an integral part of their current mix and future plans to decarbonise their energy supply. Another group of countries, including Germany, emphasises the role of natural gas in replacing dirtier coal and complementing renewables for years to come. Commission President [Ursula] von der Leyen argued that her team had presented the delegated act on nuclear and gas because, while Europe needed more renewables, it also needed “a stable source, nuclear, and during the transition, gas.”

Aside from providing state funds, it is important to attract much-needed private investment for the path each country chooses to get to a climate neutral economy. Thus, joint rules for such private investments have led to the dispute at hand, as they could make one or the other path more expensive, for example through higher risk premiums.

At the heart of the spat is the question of whether or not the two technologies can be considered sustainable under certain circumstances. Fossil gas is a potent greenhouse gas and will have to be largely phased out eventually. However, it causes less CO2 emissions when burned than coal, which could help countries clean up their heating or power production in the short and mid-term. In addition, some of the infrastructure could be converted to renewables-based gases like hydrogen in the future. Nuclear power, on the other hand, is often seen as a stable source of energy with near to zero greenhouse gas emissions. However, new plants take years to be built, so their contribution to climate change mitigation – very much a near-term challenge – is questioned. In addition, nuclear power facilities generate radioactive waste for which a solution has yet to be found. Germany is among the states rejecting the inclusion of nuclear.

7. Will the taxonomy fulfil its aim if nuclear and gas are included as planned?

Environmental NGOs, investors, members of the EU Parliament, national authorities and others have objected to classifying either nuclear, gas or both technologies as sustainable.

The EU Platform on Sustainable Finance which consults the Commission on this question said it sees “a serious risk of undermining” the taxonomy with the inclusion of nuclear and gas as initially proposed by the Commission. Green group member of the European Parliament Bas Eickhout told Politico that if the delegated act remains the same as the draft presented on 31 December, it will be “a big blow to the EU’s credibility as a climate leader.” United Nations-supported investor network PRI warned that the inclusion of gas-fired power “would seriously compromise” the taxonomy’s role as an independent and scientific tool in line with Europe’s climate goals, as did other investor networks.

Others – such as German Chancellor Olaf Scholz – say that the debate about the inclusion of nuclear and gas in the taxonomy “should not be overestimated”. “What we are talking about here is the assessment of the activities of companies,” he said, adding that “in the end individual countries decide which way they want to go with regard to their path for an emission-free future”.

Some investors and analysts have already said that the inclusion of nuclear and gas in the taxonomy does not necessarily mean they would go for it, as clients expected a different approach. European Investment Bank (EIB) President Werner Hoyer said the institution might decide to steer clear of nuclear and gas projects, reported Bloomberg. “If we lose the trust of the investors by selling something as a green project, which turns out to be the opposite, then we cut the feet on which we are standing when it comes to financing the activities of the bank.”

8. What happens next? What are the chances that nuclear and gas will be included?

After the European Commission has formally adopted the complementary delegated act regarding nuclear and gas on 2 February, member states and the European Parliament have four months (which can be prolonged by another two months) to look at it and object if they want to. The act can only be blocked in its entirety, not just individual elements.

The bar for this to happen is high. Member state governments in the EU Council would need a “reinforced qualified majority” to do so. It is seen as very unlikely that at least 20 states representing at least 65 percent of the EU population could be reached. In the European Parliament, however, a majority in the plenary would suffice. Many observers see it as rather unlikely, but there is certainly considerable opposition to the current proposal. Should the four-month (six-month) scrutiny period end without either institution objecting, the delegated act will enter into force and apply.

Another hurdle for the delegated act is possible legal action by EU member states like Austria once the act takes effect. The government has said it could take the decision to court, but legal experts doubt the chances of success. They also point out that a court case could drag on while the act would already affect investors.