Germany’s onshore wind power expansion threatens to grind to a halt

Onshore wind power expansion in Germany has fallen to the lowest level in nearly 20 years, according to the latest figures from wind power industry associations BWE and VDMA Power Systems. For the first six months of 2019, the country’s gross expansion stood at 287 megawatts (MW) – or 86 new turbines – the lowest level since Germany introduced its Renewable Energy Act in 2000. Accounting for turbines decommissioned over the same period, net expansion was just 35 turbines, a fall of 82 percent compared to the same period last year, BWE said.

Despite the slow-down in new turbines connecting to the grid, generation in the first half of this year was up around 20 percent compared to the same period last year, thanks to strong winds in late winter. Matthias Zelinger, head of VDMA Power Systems said the sluggish rate of expansion was “a punch in the gut” for the German energy transition, and at odds with the county’s climate action goals. He also warned that Germany’s historically strong turbine manufacturing industry risked being marginalised globally.

Wind is Germany’s most important source of renewable power and vital to its energy transition. With its last nuclear power plant to be shut down in 2022 and coal power to be phased out no later than 2038, Germany aims to get 65 percent of its power from wind, solar and other renewable sources by 2030. The mechanism to support this rapid expansion of green power shifted in 2017, from automatic feed-in tariffs for anyone hooking a renewable facility up to the grid -- introduced under the Renewable Energy Act in 2000 and guaranteed for 20 years -- to a more managed approach with caps on annual expansion, and power producers competing in auctions for a share of each year’s new capacity.

Former leading market Germany to account for about 2.5 percent of global growth

New onshore wind capacity in 2014 and 2015 averaged around 4 GW annually. After the upcoming change to the system was announced, power producers raced to complete projects in time to benefit from the old system, and Germany gained 9 GW’s worth of new turbines in 2016. Following the switch to auctions in 2017, expansion has fallen to less than 1.5 GW per year, threatening the survival of German turbine manufacturers, many of which have only survived by relying heavily on exports, BWE says.

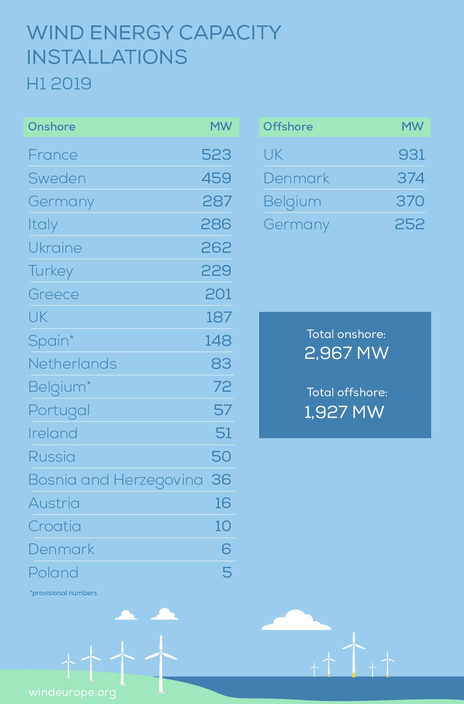

According to WindEurope, a toal of 4.9 GW onshore and offshore wind power capacity were installed in Europe in the first half of 2019. Around the world, nearly 60 GW of new wind turbines are expected to go online in 2019. The German sector would like to see new domestic capacity reach 1.5 GW this year, but Zelinger says even that would account for just 2.5 percent of the global market. “We’re definitely no longer racing ahead of anyone here,” he added. “We can -- and must -- get back on track to meet the 2030 climate target,” Zelinger said, calling for the government to create conditions now for the sector to flourish over the coming decade.

Zelinger said German manufacturers were still at the forefront of wind power technology, and most were committed to keeping production at home, “but we need to set the conditions”. That, he said, came down purely to political will, as industry players blame the slow-down on regulatory hurdles.

Construction of some 2,000 turbines with a combined capacity of around 11 GW is currently on hold due to licensing problems. These are mostly to do with mandatory minimum distances from residential areas and aviation infrastructure, or as a result of lawsuits brought by residential and environmental groups. “A lack of space and licenses is what is holding us back right now,” BWE head Hermann Albers said.

To meet climate targets, the wind power association says Germany needs an average of 4.7 GW of new onshore wind power capacity each year from now until 2050, when the country aims to go carbon-neutral. Yet Albers says new technology means the additional capacity doesn’t mean vast numbers of new turbines littering the landscape, as aging models are replaced with new, more efficient ones -- a process known as “repowering”.

Total number of turbines does not have to grow much more

Turbines already operating on German land have a capacity of around 1.8 MW, but the average capacity of new turbines -- with hub heights around 130 metres -- is now some 3.3 megawatts (MW). Albers said future onshore models could reach up to 6 or 7 MW. There are currently around 29,000 onshore turbines in Germany, but BWE estimates that by the time the country goes carbon-neutral mid century, it will need only 30,000 turbines with a total capacity of 200 GW, covering just 2 percent of German land.

To achieve this, Albers said there must be a clear strategy to repower turbines once their 20 years of guaranteed support is up and they are likely to be decommissioned. Since the Renewable Energy Act that established renewables support was introduced in 2000, for many turbines this will start to the case by 2021. Albers said wind power prices had fallen to a level where they can no longer be seen as an obstacle for more rapid wind expansion. Demanding decisive steps to give up coal, Albers said the Green parties’ strong performance in European elections pointed to citizens’ high expectations for climate action.

But he added that the government needed to do more to boost public support for wind power, resistance to which tended to be overhyped in the media. The BWE would like wind farms to be able to give up to 2 percent of their profits to local government. The BWE has also called for a “new deal” with environmental protection groups to forge a consensus over wind power expansion, through close cooperation on individual projects, and Europe-wide standards to identify risks to local bird or bat populations.

BWE said federal government, as well as the state administrations, must make it “publicly and unequivocally clear” that they plan to meet the country’s renewables targets in order to protect the climate.

Chancellor Angela Merkel’s federal government is currently working on a climate action law to be announced later this year, which will include a whole raft of proposals across all economic sectors, aimed to ensuring Germany achieves its climate targets. VDMA head Zelinger said lawmakers must draw the document up as a roadmap for the future economy, and be acutely aware that industry will see it as “a catalogue for company investments”.

More and more industrial companies are already demanding means to source their power from renewable wind, Zelinger said, and ensuring Germany remains at the forefront of renewable technology can only be an economic advantage in years to come.