German climate law put off as disagreements weigh on governing coalition

The German government coalition could be headed for a deep row over its Climate Action Law, which is intended to get the country back on track toward meeting its emissions targets, according to several German media reports. Plans by SPD environment minister Svenja Schulze to roll out a framework for the law have been put on hold after protests from Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance, the Süddeutsche Zeitung and Handelsblatt write.

Schulze wants to hold other ministries financially accountable for failing to abide by EU emissions targets. She also wants her environment ministry to be able to demand improvements in policymaking on transport, heating, agriculture and other areas seen as critical for meeting Germany’s climate targets should the other departments fail to deliver. But Schulze’s plans have been met with staunch resistance from the conservative alliance.

The CDU’s environmental policy spokesperson, Marie-Luise Dött, told newspaper Tagesspiegel that the conservatives would not accept that much power for Schulze’s environment ministry. “Under a regime of shared responsibility, it’s not possible that one ministry fills a dominating position,” Dött said. According to the Süddeutsche Zeitung, conservative politicians say the planned law “is not dead but put on hold” for now.

But Schulze’s state secretary in the environment ministry, Jochen Flasbarth, insisted the row would not endanger the government’s timetable. “We will of course implement the coalition treaty’s provisions for climate action, one by one. This includes a Climate Action Law that ensures we meet the 2030 climate targets,” Flasbarth wrote on Twitter.

Shaky coalition

The coalition agreement between the CDU/CSU and SPD calls for a Climate Action Law to be introduced in 2019. But the coalition got off to a rocky start in 2018. Internal rows over immigration slowed down other policymaking initiatives relevant for the country’s Energiewende, the dual shift from nuclear and fossil fuel to a renewables-based climate-friendly economy. Many observers have wondered if the coalition can muster the strength to push through ambitious legislation on climate as both conservatives and Social Democrats have seen severe losses in regional elections, losing ground to both right-wing populists and the Green party. With the European parliament elections in May and votes in East German mining states due in autumn, commentators have started to speculate about an early end to the current coalition.

However, the SPD-led environment ministry continues to voice confidence about the Climate Action Law. “We’re still on schedule,” a spokesperson for the environment ministry (BMU) told Clean Energy Wire.

The BMU said the law’s first draft is being finalised and should be ready “within the next few days.” The environment ministry has called on other ministries to submit planned measures for emissions reduction by the end of March. “This is one of the government’s key policy projects,” the BMU spokesperson said, adding that a decision is needed soon so that industry can prepare for the new legal regime.

The BMU’s approach is to split the Climate Action Law into two separate sections. The first part would set CO2 budgets for individual sectors, with the possibility of setting maximum annual emissions levels. The second part will include a suite of government policies, which will be decided after the ministries submit their plans. The current proposal includes a measure allowing the environment ministry to amend laws that technically fall under the responsibility of other ministries but are deemed essential for climate policy. Germany’s conservatives vehemently oppose this additional authority for the environment ministry.

Environment minister Schulze repeatedly stated that she wants Germany to get back on track toward meeting its emissions reduction targets under the Paris agreement, after the government had to admit that the national targets for 2020 are now out of reach. She wants to make sure the next major round of emissions targets, set for 2030, are not missed in the same way.

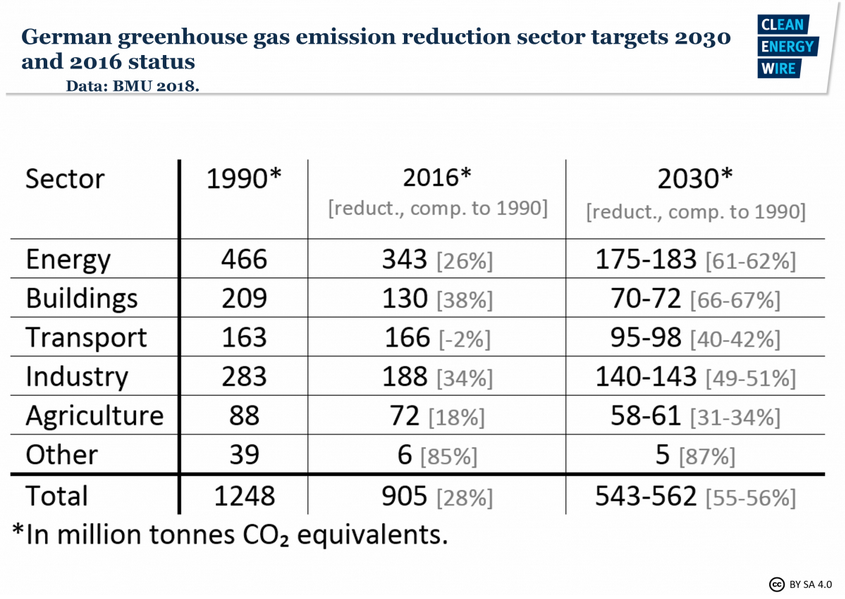

Under those targets, Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions should be reduced 55 percent below 1990 levels by the end of the next decade. A set of sectoral targets in the country’s Climate Action Plan 2050, passed during the previous legislative period, is meant to ensure progress and provide guidelines for the ministries submitting their individual climate action measures.

According to the BMU, the measures for the energy sector are largely outlined in proposals from Germany’s coal exit commission. The agriculture ministry has also submitted proposals, but so far the government has not produced plans for the other relevant sectors, transport and buildings, and there are few signs that deliberations are proceeding smoothly.

The independent transport commission is supposed to come up with recommendations similar to those developed by the coal commission. But it has recently made headlines for a row between CSU transport minister Andreas Scheuer, and experts on the commission, after it emerged that the commission might consider a speed limit for German highways and higher fuel prices. “Demands that provoke anger, bring about burdens or endanger our prosperity will not become reality and I reject them,” Scheuer said about the leaked “list of ideas,” from the commission.

Things are not looking much better for the buildings commission, which falls under CSU interior minister Horst Seehofer. In mid-February, reports emerged that the commission, tasked with finding ways to curb emissions in heating and construction, might not be appointed as planned, leading to criticism from industry representatives. “This is not responsible policymaking,” said Andreas Mattner, head of the German real estate federation ZIA.

Germany might have to pay billions in fines after failing to comply with EU emissions reduction targets in the agriculture, transport and heating sectors, which are not covered by the Union’s emissions trading system (ETS). Schulze wants those payments to be drawn from the responsible ministries’ budgets, and she wants her own ministry to be able to impose changes on policy proposals it deems insufficient for meeting reduction targets.

Another contentious issue is the proposal for a national carbon price. As early as March 2018, Schulze said that she considers a national carbon price as a possible key element of Germany’s reformed climate policy architecture. But the new state secretary for energy in the CDU-led economy and energy ministry, Andreas Feicht, swept that proposal aside in his first appearance at a major energy industry event,saying that there would be no price on carbon emissions during the current legislative period which runs official until autumn 2021.

Meanwhile, Georg Nüßlein, deputy parliamentary group speaker of the CDU/CSU has argued that the country’s planned coal exit would consume so much of the government’s financial resources for now that “there’s little room for other climate action measures” A price on carbon emissions could lead to resistance by those most affected by rising fuel prices, Nüßlein argued.

School student strikes add pressure on government

While a number of politicians from the business-friendly wing of the conservatives have attacked the coal compromise and first estimates by energy company RWE of compensation for switching off coal plants early as proposed have also ruffled feathers, the environmental NGOs emphasised that the exit had to go ahead at the speed suggested by the commission. Energy state secretary Feicht meanwhile said in a video statement published on Twitter the ministry was working on the implementation of the coal exit proposal. “There is no way back,” he said. "We will have no coal-fired power generation anymore by 2038 at the latest."

The government is also facing pressure from a growing student movement, Fridays for Future, in which German students have protested on Fridays in recent against inadequate climate action.

The movement, started by 16-year-old Swedish student Greta Thunberg, has been gaining momentum in Germany. High school students have gone on strike in cities up and down the country. While many climate activists, NGOs and politicians from the Green Party have praised the students’ engagement, conservative commentators have mocked them for “skipping school” and the state of North Rhine-Westphalia recently sent a letter to school heads pointing out that school attendance must be enforced.

Some climate activists jumped on remarks by Chancellor Merkel during the Munich Security Conference, which they felt insinuated that the Fridays for Future protests have been influenced by outside actors. However, Merkel’s spokesman Steffen Seibert later clarified that the Chancellor backed the young people’s engagement. “Chancellor Merkel named #FridaysForFuture as an example of mobilization through campaigns on the web. She explicitly approves the student’s engagement for climate policy,” Seibert said in a statement on Twitter.