Energy transition's resource needs difficult to reconcile with clean supply chain ambitions

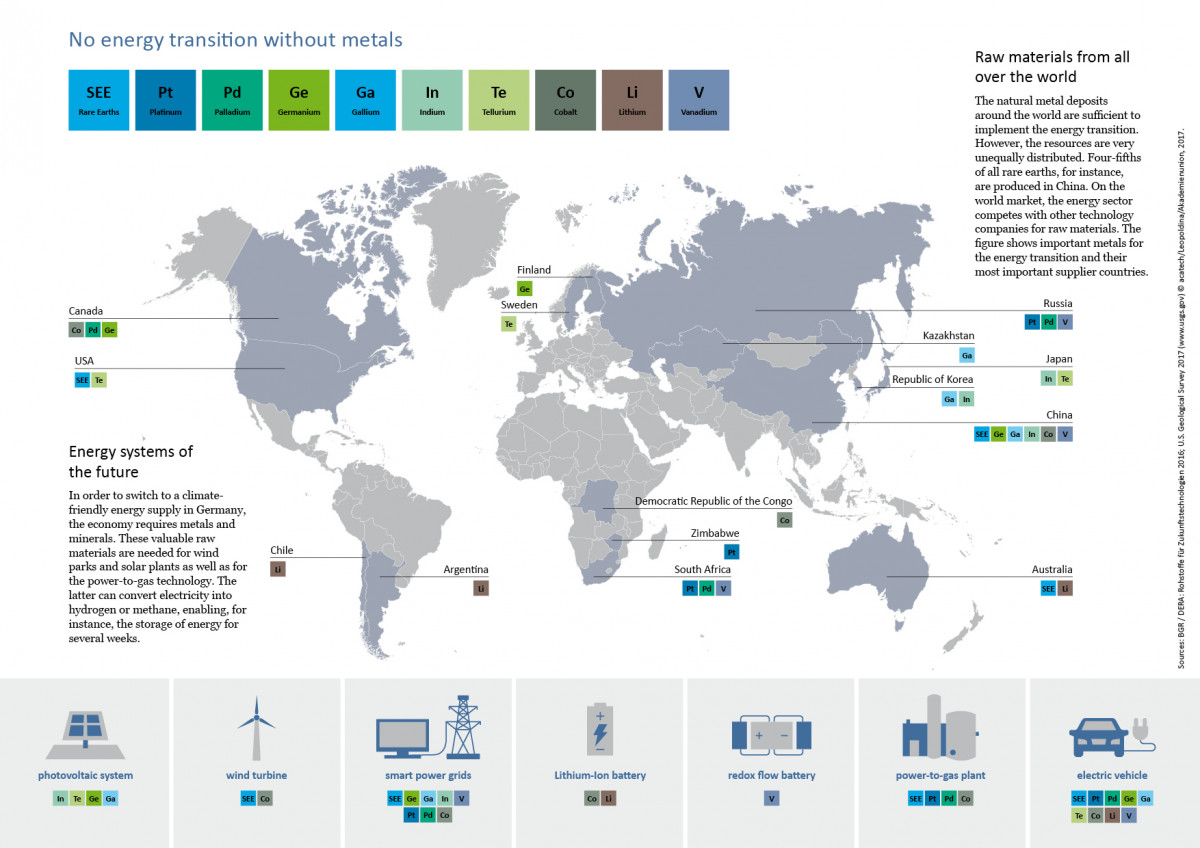

Renewable energy sources and power storage technologies are the key ingredients of worldwide efforts to put the global economy on a more sustainable path. For over two decades, Germany has been at the forefront among countries seeking to accomplish an energy transition that boosts the capacity of renewable power sources and reduces the dependence on fossil energy imports. But while wind power turbines and solar panels tap into natural energy flows that are seemingly available in infinite amounts, producing these installations at a large scale will in the first place require vast volumes of non-renewable resources. Germany's demand for oil, coal and other fossil power sources is thus set to decline. But estimates by the World Bank say that global demand for a wide range of raw materials is actually going to increase amid the energy transition, concluding that "relatively little analysis was conducted on the material implications" of the Paris Climate Agreement.

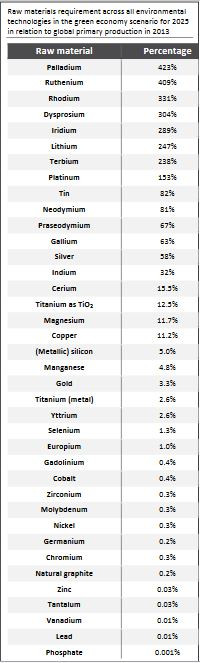

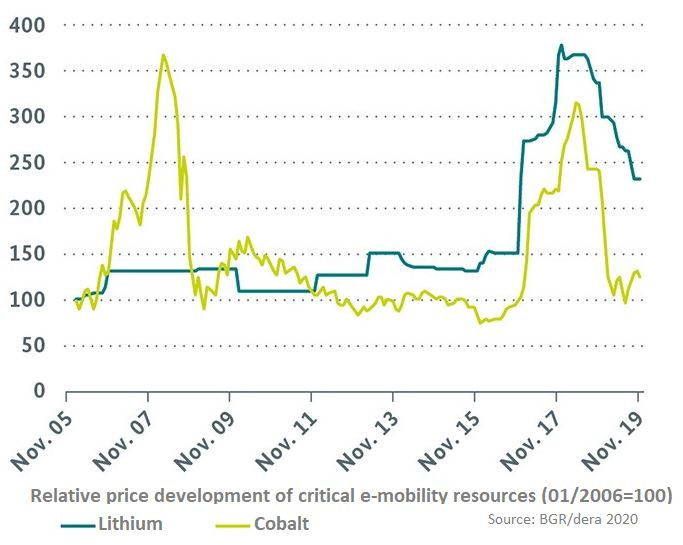

Sustaining the shift towards a climate-neutral economy means inflating demand for precious and special metals like rare earth minerals, platinum, cobalt, silver or lithium and for already widely used basic metals like aluminium, copper or nickel. Demand for platinum, for example, is set to increase sevenfold over the next decade, primarily due to the expected boom in hydrogen production, which Germany regards as a pillar of its decarbonisation plans. Moreover, e-car batteries and other storage applications could mean that Europe would use almost 60 times more lithium and 15 times more cobalt in 2050 than it did in 2020. For Germany, the world's second largest importer of metals in 2018 behind China, this has immediate consequences. Even though it has lost almost all its solar panel production to cheaper Chinese competitors, its companies hope to regain market shares with better and cleaner products. And with several leading wind power companies, a quickly growing electric car sector and other green technology, it continues to be a key manufacturing site for the global energy transition. The domestic development and production of renewable power technology and especially of e-cars are seen as a hedge against disruptions to its strong industrial base amid its transition into a climate-neutral future.

Mining responsible for up to half of global emissions

Increasing reliance on raw material imports is posing a dual challenge for Germany and other countries on a similar trajectory. First, it means competition for resources needed to build wind turbine generators, batteries, solar cells and also vast stretches of new power lines is going to increase as a function of international compliance with climate targets. The danger of possible supply bottlenecks for materials where this had previously been unheard of has been addressed both in Germany's national resource strategy and the EU's Action Plan on Critical Raw Materials. These simultaneously aim to secure open access to international reserves that could increasingly become strategic bargaining assets for major exporting nations and to develop better exploitation of whichever precious deposits for future technologies can be found within their own borders. Domestic sourcing in this case could be expanded both through new mining projects in Europe and, crucially, through better recycling procedures for millions of tonnes of electronic and industrial waste accrued each year.

Secondly, it raises questions about the environmental and social impact of a spike in mining activities. A 2019 UN analysis found that extraction and processing of metals and minerals may account for half of global greenhouse gas emissions and up to 90 percent of biodiversity loss and water stress. Poor environmental standards for mining of energy transition resources could at worst weaken the emission reduction effect of each renewable power installation. Efforts to guarantee a more sustainable production process and prevent raw materials from becoming the energy transition's weak spot have been urged by NGOs and institutions like Germany's environment agency (UBA) for years. But while attempts to introduce tighter regulation to ensure sustainable and fair supply chains are making headway at the European level, Germany's government has so far been caught up in brawls over legally binding mechanisms for importers and lets companies take voluntary action instead.

But the need to secure access to renewable energy resources amid fast-growing competition and the aim to simultaneously soften the impact of sourcing activities are poised to clash sooner or later, industry groups warn. "There is a target conflict between the resource strategy's aim to secure access to raw materials and the supply chain law's ambition to exclude suppliers that do not comply with social and environmental standards," Sebastian Schiweck of metal industry group WVM told Clean Energy Wire. The law proposed by Germany's ministries for development cooperation and for labour has been rejected by large parts of the industry as well as the economy ministry especially. Its aim to make importing companies fully responsible for enforcing social and environmental minimum standards in supplier countries has particularly irked businesses. According to Schiweck, the law in its proposed form would "definitely have a negative impact on our resource supply security."

Europe's poor resource endowment leaves little wiggle room, industry says

Metal and mineral importers and companies processing these raw materials are clearly benefitting from the shift to low-carbon technologies, the WVM said. While the industry group "of course" agreed that ensuring greater compliance with social and environmental standards would often be desirable "in principle" among source countries as diverse as the DR Congo, China or Canada, Germany would remain a "price taker with little influence to enforce its ideas on the market." Despite budding attempts to scale up domestic lithium mining for e-car batteries and other still mostly rather small-scale ventures into exploring Europe's own energy transition resource potential, the region's relatively poor resource endowment would leave little wiggle room to change suppliers if they are found incompliant with ambitious standards. "We depend on imports for almost 100 percent of the metallic resources that we use. Europe as a whole cannot be self-reliant when it comes to metal supplies," Schiweck said.

Obliging companies to certify compliance down to the very origin of all input components of any product among up to 5,000 direct suppliers would therefore border on the impossible for some companies, metal industry representative Schiweck said. Especially those processing raw materials into intermediate goods as the first supply chain link in import countries could easily become overstretched, he argued. Joint EU efforts, such as the European Raw Materials Alliance launched at the end of 2020 and backed by more than 150 companies from the sector, could help to bundle bargaining power and improve enforcement, but supply security would have to remain the chief concern. Rules already in place would often simply be ignored, he added. "There will always be some residual risks that cannot be entirely ruled out.

Industry umbrella federation BDI echoed these concerns, saying that a secure raw material supply for high-tech products would too often be "taken for granted." There is a growing tendency to use quotas, tariffs or other trade restrictions on strategic minerals as political assets by source countries. While there is reason for optimism that a shift to renewable power will overall reduce conflicts over resources compared to the fossil age, the question who controls the levers to energy supply already plays a vital role in geopolitical modelling of the future and could alongside with global warming become a source for violent struggle. Besides that, bustling competition between green technology manufacturers from Europe, the US, China, Japan and other advanced markets would make it increasingly difficult to enter into long-term contracts with suppliers, a prerequisite for implementing "the highest social, environmental and human rights standards" that the German industry adheres to. Ultimately, however, industry could not perform "tasks of the state," such as ensuring compliance with human rights in source countries, the BDI argued in a position paper.

Consumers could compel companies to comply

For Michael Reckordt of NGO PowerShift, the state could perform this task by tightening supply chain regulation. "It could really make a difference in supplier countries," Reckordt told Clean Energy Wire. Existing flagship mechanisms like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) would usually focus on financial reporting standards to curb corruption and not to target social or environmental production conditions. A supply chain law, on the other hand, would require much more scrutiny, he argued.

Some large consumer electronics producers have already made efforts to prove that the materials used in their devices come from certified smelters. Other industries, like carmakers, would start to follow that example. Those who apply tougher standards would face costs to do so, which is why levelling the playing field by setting tighter standards would only help to make competition fairer, Reckordt said. "It is very well possible for large companies to completely retrace supply chains. It's something they need to be capable of to guarantee material quality standards anyway." But instead of the state, the imperative to establish a high degree of transparency could also come from a different end – the customers. "You'll lose market share today if your product is seen as a conflict driver." And this constraint would by no means spare producers outside Germany or the EU. "Chinese and other Asian companies are also facing a surge in demand for better certified products," especially if they attempt to gain a foothold in lucrative Western markets.

The view that greater emphasis on environmental and social considerations in supply chains could ultimately benefit companies is backed by a study conducted by environment agency UBA. Implementing due diligence measures would not only be feasible but also become an advantage given the trends on financial markets, for example the EU's taxonomy for identifying sustainable finance criteria, that are expected to mandate tighter controls of business externalities across the board. "It should be in the companies' own interest to identify risks early, make them transparent and consistently work on removing them," the agency said after a government survey among over 2,200 companies revealed that only about five percent of them conducted adequate compliance reporting. Multiple civil society groups have since joined an initiative to introduce a supply chain law and close the gap between what companies say would be desirable in theory and what happens in practice.

But for PowerShift's Michael Reckordt, obliging producers alone won't be enough. Retailers too could do their part by promoting certified products and shunning others. Consumers not only would have to be ready to accept rising prices if better standards are established but also make up their mind how much physical resources they want to use to satisfy their own demands and needs. "Given that resources for renewables and also the renewable energy they produce become more and more precious, we need to ask ourselves if we really want to keep building cars that weigh two tonnes or more to transport a person weighing 80 kilograms."