Moorburg power plant – Last of a dying breed, or the future of coal in Germany?

After an 11-year planning and building odyssey accompanied by much criticism from commentators and environmentalists, the first unit of a large new hard coal-fired power plant in Moorburg, Hamburg went online in early March 2015. The 830 megawatt Vattenfall project was headlined “Greetings from the Stone Age” in one newspaper, a sentiment echoed in much of the unusually heavy national media coverage.

Much of the German public sees investment in fossil-fuelled energy as in conflict with the aim of building a low-carbon economy fed by renewable energy, a generational project called Energiewende (energy transition). And observers from the green community say it will be nearly impossible for Vattenfall to profitably operate the station, which consumes up to 4.2 million tonnes of coal every year, because more and more power is generated from renewables and prices on the electricity exchange have plummeted in recent years.

If coal is so reviled and potentially unprofitable, will Moorburg's second unit, scheduled to become operational in summer 2015, be the last of its kind? Has Germany, where the government has taken great care to avoid the words “coal phase-out,” made it so uncomfortable to invest in coal plants that new additions to the existing fleet are out of the question?

In April 2014, the German Association of Energy and Water (BDEW) said that five hard coal- and four gas-fired power stations were set to become operational in 2014 and 2015. Indeed, four hard-coal generating units went online in 2014 and early 2015 with three more scheduled to start this year or in 2016. But planning for these plants began as many as 10 years ago. Current market conditions, which are looking less and less favourable for coal, make it uncertain whether such long-term investments will bring reliable returns in the future.

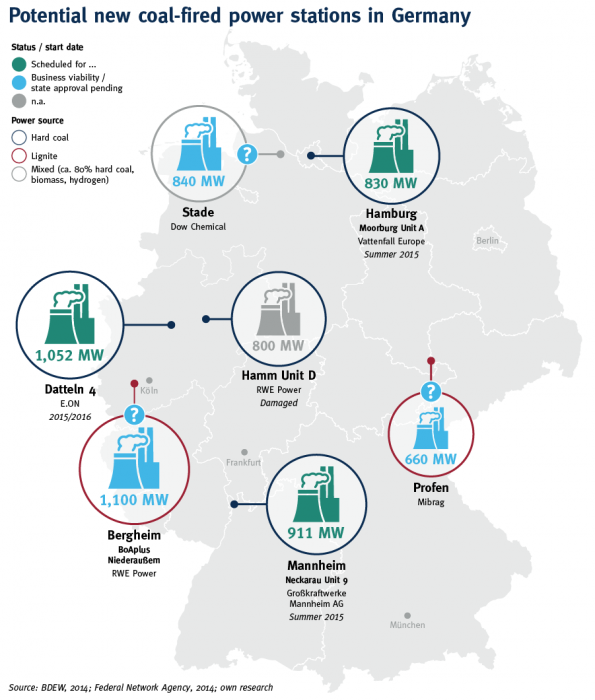

According to BDEW, Federal Network Agency and CLEW’s own research, one other hard coal unit and two lignite stations are currently in the state approval procedure that might easily take another two years (See Figure 1). The BDEW lists utility Mibrag in eastern Germany as planning to open a new lignite-fired power station in Profen (Saxony Anhalt) in 2020 but it is still in the approval process. The RWE lignite project BoAplus in Niederaußem (North-Rhine Westphalia) is also in the state approval process, but whether it will be built is not certain.

“Under the current market conditions, we would not built BoAplus," a RWE spokesperson told the Clean Energy Wire. “Once the approval process is completed, we will check the economic conditions again and decide whether construction begins or not.”

In April each year, the BDEW publishes a list of planned power stations. “One thing is clear already: The situation on the power station market has become even worse,” BDEW chairwoman Hildegard Müller told the Clean Energy Wire. Referring to a recent survey by the BDEW, she said that two thirds of all power producers in Germany are losing money from conventional electricity generation.

While the coal plant in Moorburg won't be the last of its kind to go online in Germany, planning has largely come to a halt as most utilities consider market conditions under the Energiewende unfavourable to investment in fossil-fuelled power stations.

With the growth of renewables, which covered 27.8 percent of German power consumption in 2014, power prices on the exchange fell. Today and in the near future, Germany will continue to have power overcapacities (See CLEW's Factsheets on Utilities and Merit Order Effect). While operators of lignite and nuclear power stations often simply kept their facilities running, hard coal- and gas-fired power stations scaled down production at times of high input from renewables, the Fraunhofer ISE found in 2013.

Economists consider spending on new hard coal plants “stranded investments,” researchers at Green Budget Germany (FÖS) wrote in March 2015.

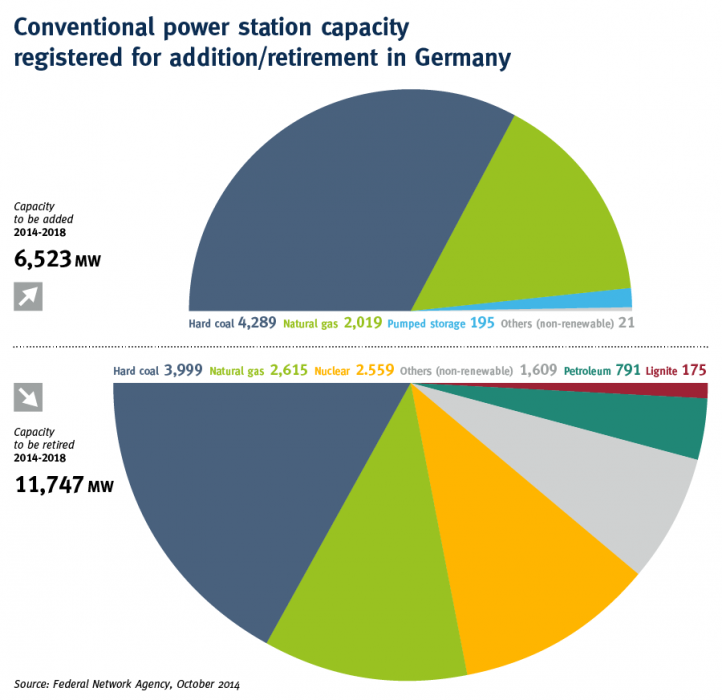

“The uncertainty for investors is becoming ever larger and the economic pressure on existing power stations is increasing constantly,” Müller said. Apart from the dwindling planning of new stations, utilities have asked for 48 station units (including hydro power and gas plants) amounting to 8 gigawatts (GW) of capacity, to be permanently retired or mothballed. According to the Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur), over 11 GW of conventional power station capacity (including nuclear energy) is slated for retirement by 2018, compared to 6 GW to be added (See Figure 2).

However, some 16 GW of renewable energy capacity (wind, solar, biomass) will be added by 2018, according to projections by the transmission grid operators. Even though these renewable sources do not provide electricity as consistently as conventional power stations, the power they produce will offset the retired fossil capacity.

Because the services of conventional power stations are no longer required around the clock, but only at times when photovoltaic and wind installations don’t generate sufficient power, or system stability is required, the BDEW and utilities advocate a new power market design that would compensate them for keeping fossil plants on standby in case of cloudy skies and low wind (See CLEW's Dossier on German power market reform).

“We’re not talking about subsidies, but about a market for secure capacity,” Müller said. But so far, both energy minister Sigmar Gabriel and Chancellor Angela Merkel have been critical of a capacity market, instead advocating a reformed energy-only market. In this scenario, price peaks at times of electricity scarcity would help compensate plants whose power is rarely needed. Müller says this is a risky strategy.

Alternatives for industry

Some thermal power stations are built not to provide power for the general public, but to ensure a steady supply for large industries. Such on-site units power the production facilities of Bayer, BASF and other large industrial consumers. Their viability is not purely determined by the retail power price, but by an overall cost-benefit analysis in which security of supply plays an important role. Hence, Dow Chemical Germany, part of the US-based Dow Chemical Company, is planning an 840 MW combined heat and power station at its site in Stade, Lower Saxony.

Dow's state-of-the-art plant will use a combination of hard coal, natural gas and hydrogen, with hard coal probably making up 80 percent of the fuel in the start.

The company’s leadership is convinced that a large power consumer like Dow Chemical, which not only needs a steady supply of electricity but also heat, is right to invest in their own fossil-fuelled power station, Joachim Sellner, spokesman for Dow Chemical in Stade told the Clean Energy Wire. And market conditions for investing in the new unit are not bad, Sellner said. “People will see that industry needs large power stations, because there will be windless nights.”

Despite record low electricity prices on the exchange and the current power market debate, Dow Chemical Germany, which consumes around 20 terrawatt-hours of energy a year, has not seen the need to significantly adjust its plans regarding the new power station at any point in the seven-year planning period, Sellner said.

The eco aspect

Some believe that Germany still needs to ensure the survival of fossil power stations in the power market and they are advocating further investment in this area. As Müller puts it: “The idea to phase out nuclear power and coal at the same time cannot work – both for technical and economic reasons.”

But this collides with the view of researchers and politicians promoting Germany’s greenhouse gas reduction targets. “Whether you want to call it a coal phase-out or not, we have clear CO2 reduction targets, and that means we have to reduce our use of fossil fuels,” Felix Matthes Research Coordinator at the Institute for Applied Ecology (Öko-Institut) said at a conference in February 2015. Almost 40 percent of Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the electricity sector.

Climate Alliance Germany, a cooperation of environmental organisations and other NGOs, says that “despite the oversupply of power and the resulting decline in prices on the exchange, coal power stations are mothballed far too late.” One third are more than 40 years old and still producing power. “That’s why we need an effective law to limit emissions from the power sector, as the government has announced for this year,” the Alliance said in a statement in early March.

The fossil power station fleet in Germany is ageing. Lignite-fired power stations run for an average of 55 years, according to Climate Alliance. Seen in this light, it isn't new stations like Moorburg that are “dinosaurs”. Old plants - which in the case of lignite - have even increased their production should be targeted first, Hauke Hermann, senior researcher at the Öko-Institut told the Clean Energy Wire.

Vattenfall’s new units in Moorburg have a net electric efficiency of 46.5 percent. When the combined production of heat from the plant is included, fuel utilisation reaches up to 61 percent. The Federal Environment Agency (UBA) estimated the average fuel efficiency of Germany’s hard coal-fired power plants at 41 percent in 2011 (lignite: 38 percent; natural gas: 55 percent).

“If we talk about climate protection, we have to talk about the old existing power stations,” Hermann said. “The decisions to build the power plants that are coming online now and in the next few years were taken five to ten years ago. And because they are more efficient than their predecessors, they have the potential to lower Germany’s CO2 emissions – provided old plants are closed at the same time,” he said.

A future for coal in Europe?

Judging by the difficulties their traditional business of running large fossil-fuelled power stations now faces, utilities – in Germany as in the rest of Europe – are likely to be wary of investing in new fossil fuel capacity until the political and market framework is more clearly defined.

Wholesale power prices have dropped in many European countries and market conditions have changed, with countries like the UK, Belgium and France introducing capacity markets and/or implementing emission performance standards (UK). CO2 emission reduction is a European goal as much as a German one, as is the growth of renewables.

In its 2014 annual report, Germany’s second largest energy company, RWE, had to book unscheduled impairments of 600 million euros on power stations in Germany and the UK. E.ON, Germany’s largest utility, also had to write off 4,802 million euros last year for unscheduled impairments on fixed assets, including conventional power stations in the UK, Sweden and Italy.

German consultancy Ecoprog published a study in 2012, saying that “investments in constructing new coal power plants are increasing again in Europe”. Despite criticism over CO2 emissions, the study expected around 80 power plant units to be built or replaced by 2020.

Now, Marcel Siebertz, one of the study’s authors, says that market conditions for coal power plants have changed significantly in the last three years. “Across Europe, energy utilities announce the mothballing of coal and gas power plants,” Siebertz told the Clean Energy Wire. But some countries, like Poland, still rely on coal power generation to ensure security of supply, he added. “In sum, investments are still ongoing because coal will remain important. But compared to 2000, investments will slow down in the next five to ten years.”

Activists from the platform CoalSwarm who have identified the status of 3,900 proposed coal power stations globally, have found a similar picture – two thirds of projects planned in 2010 have been either postponed or abandoned.