Battered utilities take on start-ups in innovation race

Contents

Decarbonisation, decentralisation, digitalisation

There is no alternative

Germany’s battered utility champions have no choice but to reinvent themselves in the face of tumultuous upheaval in their home market.

Their long-cherished business model of selling kilowatt hours generated in massive power plants “is history”, says Peter Terium, the former CEO of utility giant RWE, and now head of the company’s renewable spin-off called innogy.

He warns his industry must brace itself for new shock waves, because the turmoil caused by Germany’s switch from nuclear power and fossil fuels to renewables is far from over.

“It’s about radical change,” Terium told young energy entrepreneurs in early 2017. “It’s about three D’s - the three megatrends decarbonisation, decentralisation and digitalisation.”

He added even his company, with around 40,000 employees, must behave like a start-up to fend off rapidly encroaching new competitors in the new energy world: “We had better disrupt ourselves before someone else does it.”

One such fast-growing company bent on disrupting Germany's energy giants is Sonnen, which sells batteries that can power households, and links up users in a virtual electricity network.

“Our aim is to build the utility of the future, which will be based on a sharing economy. We’re very clear: Within ten years, we want to become larger than E.ON, and be one of the dominant players on the German power market,” Sonnen managing director Philipp Schröder told the Clean Energy Wire.

Currently, Sonnen's sales are roughly 1,000 times smaller than E.ON's. But the tide has turned, according to Schröder.

“Traditional power companies have become obsolete. They know they will never again earn money with their old business model, and this is why they try and exit it as fast as possible."

RWE, E.ON, and their traditional utility rivals EnBW, and Vattenfall – which used to be called “The Big Four” – are shellshocked by the pace of change in the industry, and by the arrival of an entirely new breed of competitors, from start-ups to IT giants.

Entranced by buzzwords like “the all-electric society”, “smart grids”, “the storage revolution”, and “blockchain technology”, they are desperate to innovate their way out of rapidly eroding business areas.

Opinion is divided on whether the former champions stand a chance in this new energy game. Some experts believe they are too cumbersome and inflexible to reinvent themselves, while others argue their size and punch will remain valuable traits under a new set of rules.

At least there is broad agreement that the struggle of Germany’s utilities deserves close attention, because it foreshadows a battle that still lies ahead elsewhere.

“The fate of the utilities in Germany offers lots of lessons for other countries – huge lessons,” energy expert Gerard Reid, founder of renewable advisory and asset manager Alexa Capital, told the Clean Energy Wire.

Reid believes similar revolutions will shake up the energy industry in many nations which have committed to mitigate climate change under the Paris Climate Agreement. “Other countries haven’t gone through these changes yet - but of course they will.

“If I was a utility executive, I would be looking very, very closely at what’s going on in Germany, and try to learn from that.”

A spectacular collapse

The “Big Four” were far too hesitant to embrace the shift to renewable energies in their home market. It was instead left to millions of citizens to grasp the opportunity, by fixing solar arrays to their roofs, or cooperating to erect wind turbines (For more details on the history of the companies’ misery, read the item Fighting for survival: Germany’s big utilities look for a future in the new energy world).

They were also slow to comprehend the profound effect renewables would have on their core business. Wholesale power prices plunged, eroding the utilities’ profitability, market share, and decreasing the value of their power plants by many billions of euros.

To make matters worse, the energy giants have to shoulder enormous costs for decommissioning their nuclear power plants (See factsheet Securing utility payments for the nuclear clean-up).

To slow the free fall, the utilities have shed tens of thousands of jobs. Market leader E.ON plunged from a record profit of over eight billion euros in 2009 to a record loss of 16 billion euros in 2016.

“Inside the Energiewende, there was no economic branch harder hit” than the utility sector, according to Christine Sturm, a former manager in RWE’s renewable energy arm.

E.ON and RWE finally responded to the crisis in earnest by splitting themselves in two in 2016. RWE spun off its renewable business innogy and kept its conventional power plants. E.ON took the opposite route and became a renewable utility, by splitting its fossil fuel business into a new company called Uniper. (Factsheets RWE’s plans for new renewable subsidiary and E.ON shareholders ratify energy giant’s split provide further details).

“How do you push for a new coal plant and argue for solar? Can you credibly do that as one company?” Klaus Schäfer, formerly E.ON’s chief financial officer and now Uniper CEO, told Fortune magazine. “We felt no.”

Share prices today clearly reflect where investors believe the future lies. innogy has a market value of around 20 billion euros, making it the country’s largest energy company. RWE is worth less than half that sum. Discounting its majority stake in innogy, RWE’s own businesses, including its many coal power plants, have a negative value. (The factsheet Germany's largest utilities at a glance provides an overview).

Decarbonisation, decentralisation, digitalisation

Yet despite these past calamities for the utilities, most experts believe the transformation of the energy sector has only just begun, thanks to the triple challenges of decarbonisation, decentralisation, and digitalisation.

The government’s targets for CO2 emissions reduction further increase the pressure on the companies. The goals imply that by 2030, half of the country’s coal-fired power stations will have to be taken offline, while the share of renewables will continue to rise steadily.

In the following two decades, fossil fuels will have to be phased out entirely if Germany is to reach its ambition to become almost climate-neutral by 2050. (Find further details in the factsheet When will Germany finally ditch coal?)

Utility analyst Mark Lewis, from British bank Barclays, says Germany’s effort to decarbonise its economy still entails massive uncertainties for the whole industry. This is because the future of fossil power generation hangs in the balance – and with it the shape of the entire power market.

“Germany now has clear energy industry targets for 2030,” Lewis told the Clean Energy Wire. “What we don’t yet have are the policy measures needed to achieve those targets. That is the number one priority for the German utility industry in terms of figuring out where all this will go.”

The uncertainty over the future of coal power plants casts a particularly dark shadow over RWE, given that it owns three of Europe’s five dirtiest coal plants, according to the following table compiled by British NGO sandbag.org.

In order to get a reliable income stream out of their fossil power plants, RWE and fossil competitor Uniper argue their CO2-intensive power plants are a crucial supplement for intermittent wind and solar, and should therefore be paid to provide supply security – in what experts call a capacity market. The government has so far resisted these demands.

Renewables’ share of power consumption will reach at least 50 percent in 2030, more than 65 percent in 2040, and at least 80 percent by mid-century, according to Germany’s official targets. Renewable electricity will have to increasingly power transport and heating in order to slow stubbornly-high emissions in these sectors – a process referred to as sector coupling.

This rising focus on decentral, small-scale renewable installations implies a massive shift to an energy system no longer dominated by centralised power generation, the utilities’ traditional expertise.

“Decentralisation will become a permanent characteristic of the power market, because the Energiewende core technologies - wind, solar, storage, e-mobility, heat pumps - all imply a more distributed structure,” according to an analysis by energy think tank Agora Energiewende*.

To coordinate ever more complicated networks of power generation and consumption, digitalisation will go hand in hand with decentralisation.

Complex IT systems increasingly take centre stage in the next phase of the Energiewende to balance power demand and supply. But the impact of digital technologies are likely to go far beyond this, as it paves the way for entirely new business models, upending the utilities’ speciality of selling kilowatt-hours.

Utility association BDEW says the digitalisation of the energy world makes the Energiewende “the largest ever national IT project”.

“Digitalisation is likely the next big step in this line of catastrophes for traditional utilities, with no less threatening impacts,” according to Hendrik Sämisch, head of Next Kraftwerke, a “power plant operator without any power plants”. His company has established a network consisting of thousands of small-scale electricity producers and consumers, creating a so-called Virtual Power Plant.

Sämisch believes the energy suppliers of the future “might be platforms on which customers pick the features of their contract as they currently do with cell phone plans: the features could include flat rates or floating rates for different hours of the day”.

Many experts also expect entirely new power trading models between households, which might enable them to dispense with a traditional utility altogether. Such systems could be operated using blockchain technology - which also underpins the digital currency bitcoin - and enables the secure and cheap processing and record-keeping of electronic transactions.

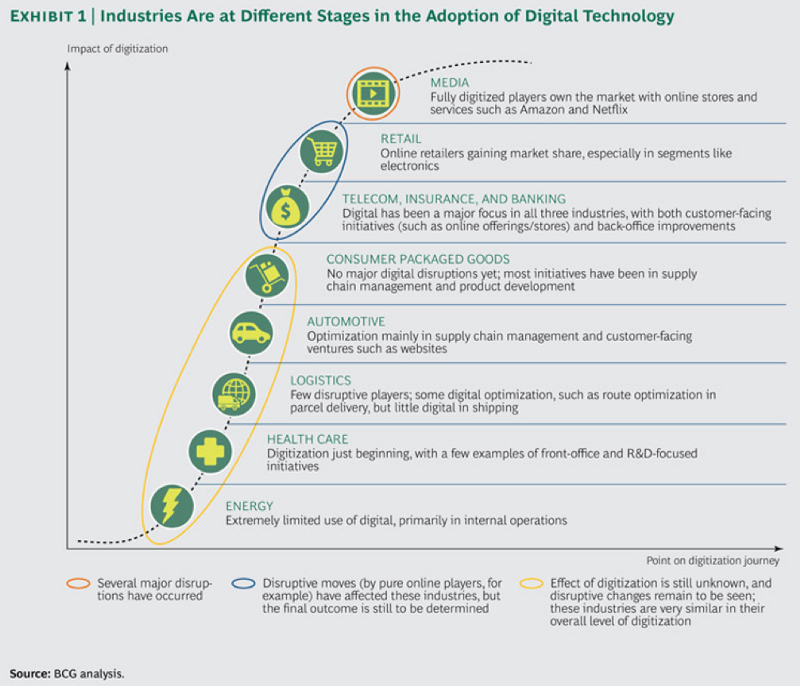

Today’s energy sector remains one of the industries least affected by digitalisation, according to the following graph by the Boston Consulting Group, implying it might have a long way to go.

Barclays analyst Lewis believes new technologies will “create all sorts possibilities we can’t even imagine today”.

“Big data, smart grids, smart meters – this is about people in their own homes taking more control of their energy consumption and being better informed. I don’t think any of this is positive for the utilities, because it gives more power to consumers, and a greater ability for them to control the volume of power they consume, and the price at which they consume it,” says Lewis.

innogy CEO Terium also braces his company for those trends: “People want to be in control, they want to be self-sufficient, they want to use and store their own energy, they want to dispatch it to the grid when it’s economical and draw from the grid on a cold, hazy day.”

Alexa Capital’s Reid believes these developments herald more trouble for power companies. “We know what the megatrends are at this point. And they’re not going to slow down. This will happen much quicker than people think.

“All the utilities’ traditional businesses are going to be under pressure – both competitive pressure and margin pressure. It starts with transmission, goes to distribution, into generation, and also their retail business. The whole value chain is going to be under pressure for many, many years to come.”

Erwin Smole, co-founder of energy blockchain specialist Grid Singularity, told enorm magazine that the utilities have to act quickly. “Either they wait and see, and end up as pure copper cable operators, or they decide now which role they can play in the future.”

Threat from outside

But defending their dominant position won’t be easy for power companies because the upheaval in the energy world creates a unique opportunity both for start-ups and companies from other industries to enter the utilities’ home turf.

The incumbents say they are fully aware of the threat. To illustrate his point that new entrants can wreck an established industry, innogy CEO Terium names Napster for music, Netflix for TV, Amazon for book stores, AirBnB for hotel chains, and Uber for taxis.

“The question I’m faced with is this: Who is going to be the Uber of the energy sector?” he asks.

Uli Huener, Head of Innovation at Stuttgart-based utility EnBW, also says new entrants pose a more important danger to his company than traditional rivals.

“The main threat does not come from our own market space. It will come from outside. Could be Google, could be Amazon, could be start-ups. They will find a niche which they are good at, and then grow rapidly.”

Sonnen's managing director Schröder says he is very sceptical the large utilities can move fast enough to withstand the attack from more agile competitors like his own company, which had around 300 employees in mid-2017, and increased sales by 70 percent to 42 million euros in 2016.

“They have understood what needs doing, but they will have a hard time, because in this market, it’s not the large players that devour smaller ones, but the fast players that devour slower ones. Google, Amazon, Apple or even Deutsche Telekom are more suited to shape the energy future than conventional power suppliers.”

Sonnen sells batteries to households, similar to Tesla’s Powerwall, but also links customers with and without solar arrays in a community so they can trade electricity with each other to cover their entire power needs. The company’s advertising is a declaration of war to established power companies: “Take your energy supply into your own hands […] This will emancipate our world from the dependence on fossil fuels and anonymous energy corporations.”

“Our clients build their own power station consisting of decentralised units. This means our grid has access to unbeatably cheap electricity, to storage capacity, to flexibility, and to load management. This pool is easily extendable to millions of households,” says Schröder.

But it is not just small start-ups like Sonnen, Next Kraftwerke and Grid Singularity that have set their eyes on the new energy world. The sector has also become a playground for giants from entirely different industries.

Carmaker BMW, for example, has teamed up with major heating systems manufacturer Viessmann to create Digital Energy Solutions. It aims to optimise small companies’ energy systems, based on the principle of flexibility, and incorporating electricity, electric mobility, and heating.

Online and telecoms company United Internet, whose brands include mail services web.de and gmx, caught the industry by surprise when it started to sell power contracts recently.

“We’re in a world where people that can embrace the opportunities offered by digitalisation – not just in energy, but also in other industries - can go in and steal advantages over incumbents,” says Reid. “That’s the challenge for the big guys: How do they embrace these technologies, and do this really quickly?”

One strategy is to team up with digital giants, and the utilities constantly announce new cooperations: Just two examples are: E.ON launched a partnership with Google to expand solar energy, while innogy joined forces with Deutsche Telekom to build fast internet connections.

Hoping for a miracle

Reid believes there is even limited scope for large power companies in renewable generation today. “The market is not growing, and there is lots of competition, because everybody wants to do it now. That makes it very difficult for the late guy to get into position there.”

An example is offshore wind - an industry which by its very nature remains earmarked for large investors. But in Germany’s first competitive auction for the technology, only two companies scored winning bids: EnBW and Danish utility Dong, both of which offered to build wind farms without support payments. Germany’s other renewable top dogs E.ON, innogy, and Vattenfall, missed out on this opportunity.

The pending electrification of transport and heating might offer some hope for the power companies’ traditional businesses.

“I would call it a big positive for the utilities if electric vehicles really do take off. This could become the first new significant source of demand growth in a long time,” says Barclays analyst Lewis.

The growth of electric mobility also entails the construction of new power infrastructure for charging stations, and utilities try to seize the opportunity. innogy is very active in e-mobility infrastructure, and E.ON recently teamed up with Danish company CLEVER to build a network of ultra-fast charging stations across Europe.

But power companies understand they also have to come up with entirely new ways of making money.

“We need to develop new businesses over the next 10 or 15 years, to cover some of the losses in our conventional business model,” explains EnBW innovator Huener.

He admits this involves entirely new strategy approaches for utilities, whose core business of building and running power stations was based on investment cycles of around 30 years. “Today, you can be lucky if a model works for five or eight years – this is how fast things are changing.”

Creating new business models also involves new approaches to risk. “Nine out of 10 start-ups fail. The one with success needs to cover the costs of nine others,” says Huener.

Huener names intelligent street lamp and mobility charging station provider Smight and decentralised energy management system Energy Base as examples of successful EnBW start-ups. But so far, total revenues from the company’s start-ups amount to five million euros, compared to EnBW’s sales of almost 20 billion euros in 2016.

EnBW hopes to generate profits of 100 million euros from new businesses by 2025 in its innovation areas Connected Home, Smart City, Sustainable Mobility, and Virtual Power Plants.

“The situation in the energy sector today is exactly the same as in computing in the 80s. You have to believe in it,” says Huener.

Innovating culture

One of the largest hurdles on the road to innovative success for the utilities lies within the companies – it means transforming corporate culture and structures.

“We have to take 20,000 people on a journey to the business models of the future,” says Huener. “Everybody knows what needs doing. The problem is always with the execution.”

innogy’s Terium describes similar problems when he says that his company has embarked upon the “biggest cultural change effort in corporate history in Germany”.

The power companies have all created separate entities to nurture new ideas, so innovations can develop outside of old company routines – so-called innovation hubs.

According to Huener, new business ideas are often difficult to implement in big companies, because they often entail the risk of undermining existing businesses: “Why would you do something that cannibalises business from within? It’s a tough problem.”

Sonnen’s Schröder argues that changing company cultures will be a difficult process for the utilities.

“They have to invest a lot of money into change management. Processes to activate employees will drain resources and strength. Even in top management, they lack competence, and without competence, you can’t take risks.”

Many of Germany’s municipal utilities also struggle with ineffective management. Their management boards are often dominated by local politicians with little industry knowledge to speak of (For more details, see the factsheet Small, but powerful – Germany’s municipal utilities).

Some industry insiders say the large utilities are still burdened by a thick layer of “monopoly flab” around their waste, leftovers from bygone years of plenty: Large numbers of overpaid but underproductive staff, expensive IT systems, and so forth.

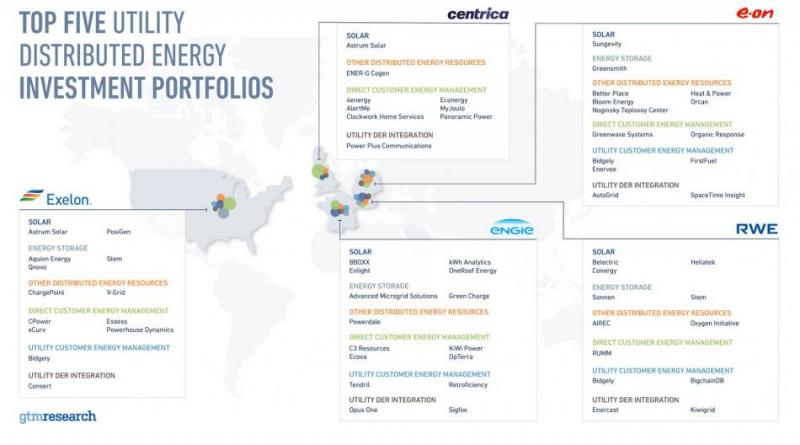

To supplement and bypass in-house innovation, German utilities have stepped up their venture capital activities and acquisition of renewable energy businesses in recent years. This graph from energy market analysis and advisory firm GTM Research illustrates that RWE and E.ON are among the top five investors in Europe and North America:

An endangered species?

Still, expert opinion is divided over whether the large utilities stand a good chance of remaining on top in the new energy world.

Andreas Kuhlmann, head of the German Energy Agency (dena), argues that it is far too early to write them off.

“I do believe big players have the potential and the strength to go full steam on trends they have identified. They do have to carry a lot of dead weight, but I think some of them will manage the transition, because in contrast to many start-ups, they have the necessary experience and size. We will need big players for the next phase of the Energiewende, old ones and new ones,” Kuhlmann told the Clean Energy Wire.

One competitive advantage they have over start-ups are millions of customers. But Schröder disputes these can guarantee their long-term survival, because “their client base is worth much less than first meets the eye”.

“Utilities have a huge problem with client retention. Even if they offer their customers new contracts with better prices, they will lose some of them, because it induces people to shop around for alternative providers.

“Similarly, if for example E.ON asked their clients: ‘Would you like one of our storage systems?’ people say: ‘Interesting idea, let’s have a look on the internet what else is on offer,’” says Schröder.

Reid agrees that many of the major utilities’ clients are happy to wave them goodbye.

“The big international companies have a problem, because their brands have a bad reputation. Many people believe they are being ripped off by big energy companies.

“It’s different for municipal utilities, for example the Stadtwerke Munich, because people believe they are important to the community and have social responsibility.”

Schröder is convinced most of the big utilities face a bleak future.

“The big utilities still have enough money and substance to play along for a while, and I wouldn’t rule out that one of them will manage the transition. But I would definitely rule out that they will all make it. Out of the large utilities, one or two will survive at most.”

Reid is similarly sceptical. He believes the industry will face a time of consolidation: “I would guess that in ten years’ time, you might have one of the large utilities left. They will be broken up and bought by other people. The market will be very different, and there will be lots of new players in it.”