The history behind Germany's nuclear phase-out

A contradictory approach? Germany wants to curb greenhouse gas emissions but at the same time will shut down all of its nuclear power stations, which in the year 2000 had a 29.5 per cent share of the power generation mix. In 2020 the share was down to 11.4 percent, and by 2023 all nuclear plants are going to be shut down. The country is pursuing the target of filling the gap with renewable energy. This factsheet provides the background on Germany’s decision to phase out nuclear energy.

The anti-nuclear movement

Germany has set itself a dual goal with its energy transition, or Energiewende: The country wants to move from fossil fuel-based energy generation to a largely carbon-free energy sector while also phasing out nuclear energy by 2023. What many international observers have portrayed as a panic reaction following the Fukushima-disaster in 2011 actually has a long history and is deeply rooted in German society.

Anti-nuclear movements started in Germany in the 1970s when local initiatives organised protests against plans to build nuclear power stations. Rallies and legal challenges against individual projects were supported locally across party lines. In 1975, 28,000 protesters occupied the construction site of a nuclear power plant in Wyhl (in the southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg) and managed to stop construction. After the accident at the U.S. nuclear power plant Three Mile Island in 1979, around 200,000 people took to the streets in Hannover and Bonn, demonstrating against the use of nuclear power. More protests followed wherever locations for radioactive waste processing and storage were considered. The anti-nuclear movement was one of the key driving factors behind the foundation of the Green Party (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen) in 1980.

The nuclear catastrophe in Chernobyl (in today’s Ukraine) in April 1986 caused widespread fear of nuclear power and strengthened the anti-nuclear sentiment. A majority of Germans were concerned about the risks of the technology. Most politicians began to stress that nuclear was a “transient” technology but not the future, and after 1989 no new commercial nuclear power stations were built. Public protests continued in the 1990s, mostly against the transport of spent nuclear fuel elements to and from waste processing facilities and prospective waste storage sites (e.g. Gorleben and Schacht Konrad, Lower Saxony).

Nuclear phase-out – opting out and back in again

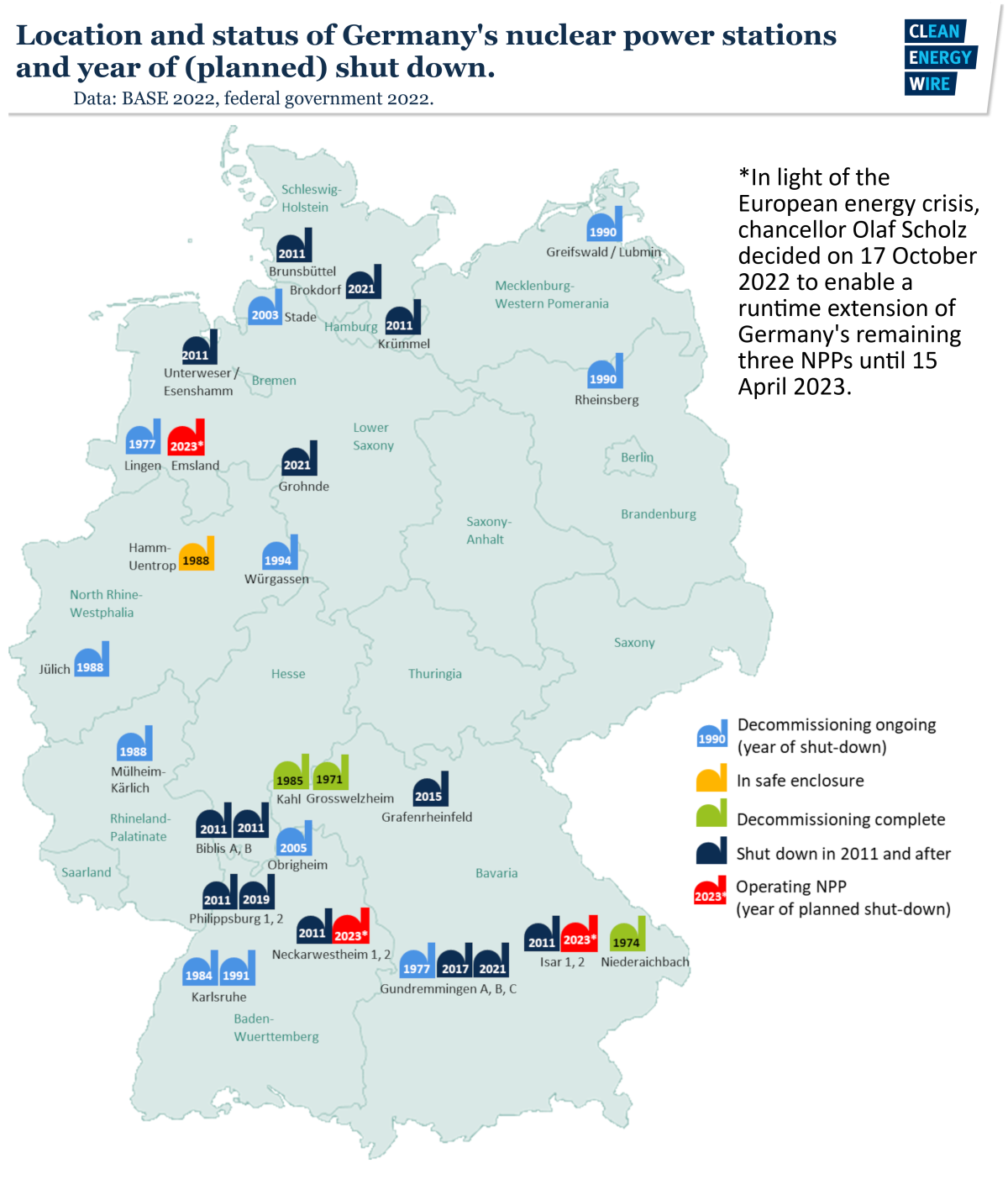

After the Social Democrats (SPD) and the Green Party won the elections in 1998, the government of Gerhard Schroeder (SPD) reached what became known as the “nuclear consensus” with the big utilities (in 2000). They agreed to limit the lifespan of nuclear power stations to 32 years. The plan allocated each plant an amount of electricity that it could produce before it had to be shut down. Because nuclear power generation can vary, the plan did not set an exact date for the complete phase-out. But in theory, the last one would have had to close in 2022. New nuclear power plants were banned altogether. The agreement became law in 2002 (Atomgesetz). Two plants (Stade and Obrigheim) were taken offline in 2003 and 2005. The opposition Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its chairwoman, Angela Merkel, objected to the agreement, calling it a “destruction of national property” that would be revoked if the CDU came to power.

When the CDU/CSU won the elections in 2009 and formed a coalition with the Free Democrats (FDP), they extended the operating time by eight years for seven nuclear plants and 14 years for the remaining ten. This became known as the “phase-out of the (nuclear) phase-out” (Ausstieg aus dem Ausstieg). Some 40,000 people went to the streets in Berlin, to protest against this decision in autumn 2010.

Fukushima and the last exit decision

In the wake of the nuclear catastrophe in Fukushima, Japan, on 11 March 2011, the same Merkel government decided on 14/15 March to suspend the 2010 lifetime-extension for a three-month period, and then to mothball Germany's seven oldest reactors for the same period (known as the nuclear moratorium). The accident in Fukushima and the reaction by Germany's federal government coincided with the hot phase of campaigning for the important election in the rich and influential state of Baden-Württemberg on 27 March 2011, where after 58 years in power the conservative CDU was under threat by the Green Party (the Green Party won and provided the state premier for the first time in Germany).

In June 2011, the government proposed to shut down eight nuclear plants for good and limit the operation of the remaining nine to 2022. Over 80 percent of parliamentarians voted in favour of the bill in the Bundestag (federal parliament). Die Linke (Left Party) only objected because it wanted a faster exit and the measure’s inclusion in the constitution.

Polls in the following years consistently showed a majority of the population to be in favour of phasing out nuclear power in the country.

Nuclear power in the global context

Despite the attention Germany gets, it is not the only country in Europe to phase-out nuclear energy. Italy, Belgium and Switzerland have also principally decided to be or become nuclear energy-free. Others such as Denmark, Ireland, Portugal and Austria will remain nuclear free.

Britain, France, Poland, Finland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary want to keep nuclear power in their energy mix and even plan to build new reactors.

The French government passed an energy transition bill in 2015, specifying that the country will reduce its share of nuclear energy from 75 to 50 percent by 2025 but said in November 2017 that this target was not realistic and would endanger the security of supply.

Japan turned off its 50 nuclear power reactors in the wake of Fukushima, but the government decided in 2014 to start operating reactors again after a security check.

In the United States, all but one of the 99 operational commercial reactors (producing about 20 percent of the total electric energy use) became operational before the year 2000. Since 2012, ten nuclear power station units are under construction, according to the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).

31 countries operate nuclear power plants. The World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2017 said that global nuclear power generation increased by 1.4 percent in 2016 due to a 23 percent increase in China but the share of nuclear power in electricity generation stagnated at 10.5 percent. It had declined steadily from a historic peak of 17.6 percent in 1996.

The average age of operating nuclear reactors was 29.3 years in 2017. As of July 2017, 53 new reactor units were under construction. While the average construction time is seven years, seven of the reactors have been under construction for more than a decade.

Between 2000 and 2013, global investment in new power plants went mainly into renewables (57 percent), followed by fossil fuels (40 percent), while only three percent of investment was spent on nuclear energy.

This Factsheet was first published in July 2015.