Q&A - Germany’s nuclear exit: One year after

Content

- How has the phase-out been conducted?

- Was there any supply security risk in the aftermath?

- What was the gap left by nuclear power filled with?

- What changed in electricity imports and why?

- Did power prices go up due to the phase-out?

- What happens with the retired nuclear plants and waste materials?

- How did the national debate about nuclear power develop?

- How did the nuclear debate move on in the rest of the world?

1) How has the phase-out been conducted?

The three last remaining nuclear power plants in Germany were taken offline on 15 April 2023. The Atomausstieg’s finalstep marked the end of a process that had been prepared for over two decades and involved almost all of Germany’s main political parties. It followed on a three-month delay caused by the energy crisis, during which the Emsland, Isar 2 and Neckarwestheim 2 plants were kept online as backup capacity for electricity generation.

The last stage of the nuclear phase-out was implemented without any technical challenges or electricity price shocks. Shortly before the deadline, citizens were worried about the possible impact of taking the final step. However, none of the most dire predictions by opposition parties and industry lobby groups materialised. “We see today that our power supply is secure, that power price dropped also after the nuclear phase-out and that CO2 emissions are going down as well,” Germany’s economy and climate action minister Robert Habeck said.

The German Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DIHK) had been a vocal critic of the final phase-out step. One year after the phase-out, there was no indication that companies experienced supply challenges related to the nuclear exit, DIHK energy expert Sebastian Bolay told Clean Energy Wire.

By the phase-out’s first anniversary, Germany had achieved a substantial expansion of its renewable power capacity. However, the country still faces challenges regarding the required grid modernisation as well as back-up and storage capacity, including batteries and green hydrogen infrastructure, to complement renewable power output.

2) Was there any supply security risk in the aftermath?

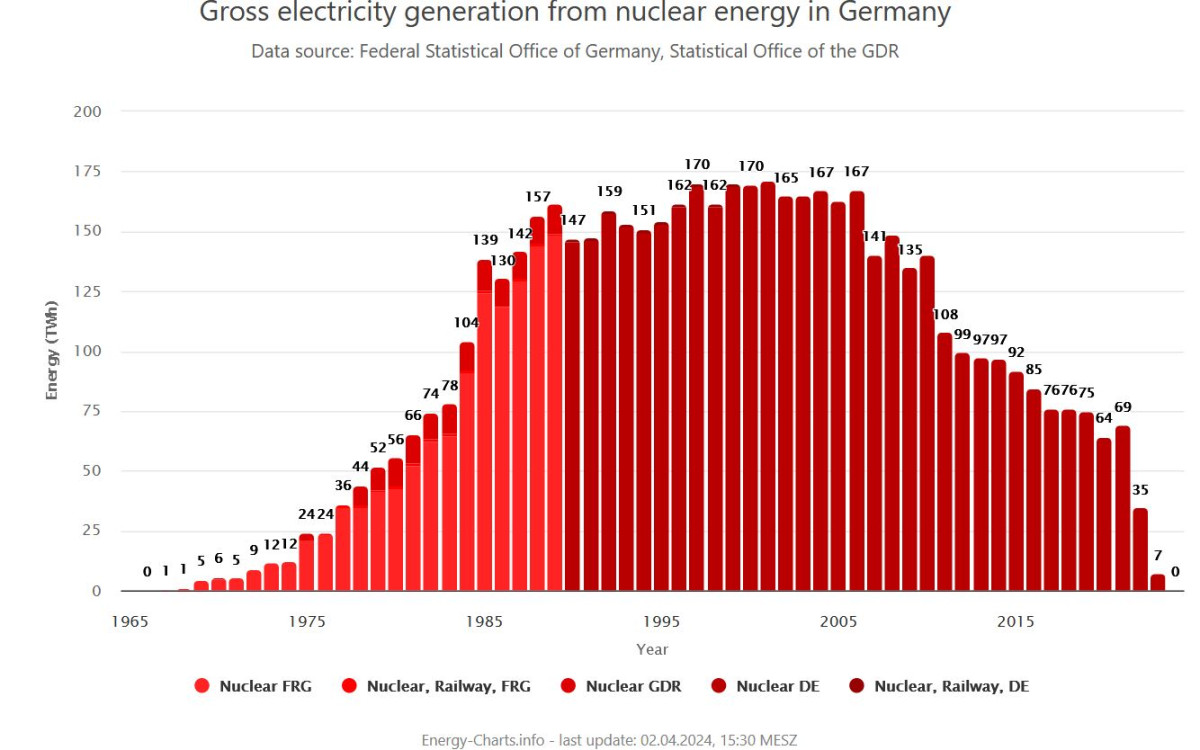

The importance of nuclear power for Germany’s electricity generation already declined significantly in the years before the phase-out was completed. In 1995, nuclear plants contributed almost 30 percent to the mix. By 2022, their share had dropped to roughly 6 percent. The share of renewable energy sources grew from about 5 percent to more than 46 percent during the same period and reached more than 50 percent in 2023.

In the winter season following the phase-out, supply security “significantly improved” compared to the previous year, the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) said, adding that greater reliability of the French nuclear fleet after its partial shutdown in the 2022/2023 period played a great role in improving stability. The risk of a larger blackout in Germany remained “very low,” the BNetzA said.

DIHK expert Bolay said some companies had reported an increase in short-term energy supply challenges throughout 2023. “Whether this was related to the decommissioning cannot be answered." However, the growing share of renewable power in the system can hardly be an explanation either. “Hourly electricity trading has a greater effect on grid stability than renewable power feed-in,” energy researcher Bruno Burger from the Fraunhofer ISE institute told Clean Energy Wire.

3) What was the gap left by nuclear power filled with?

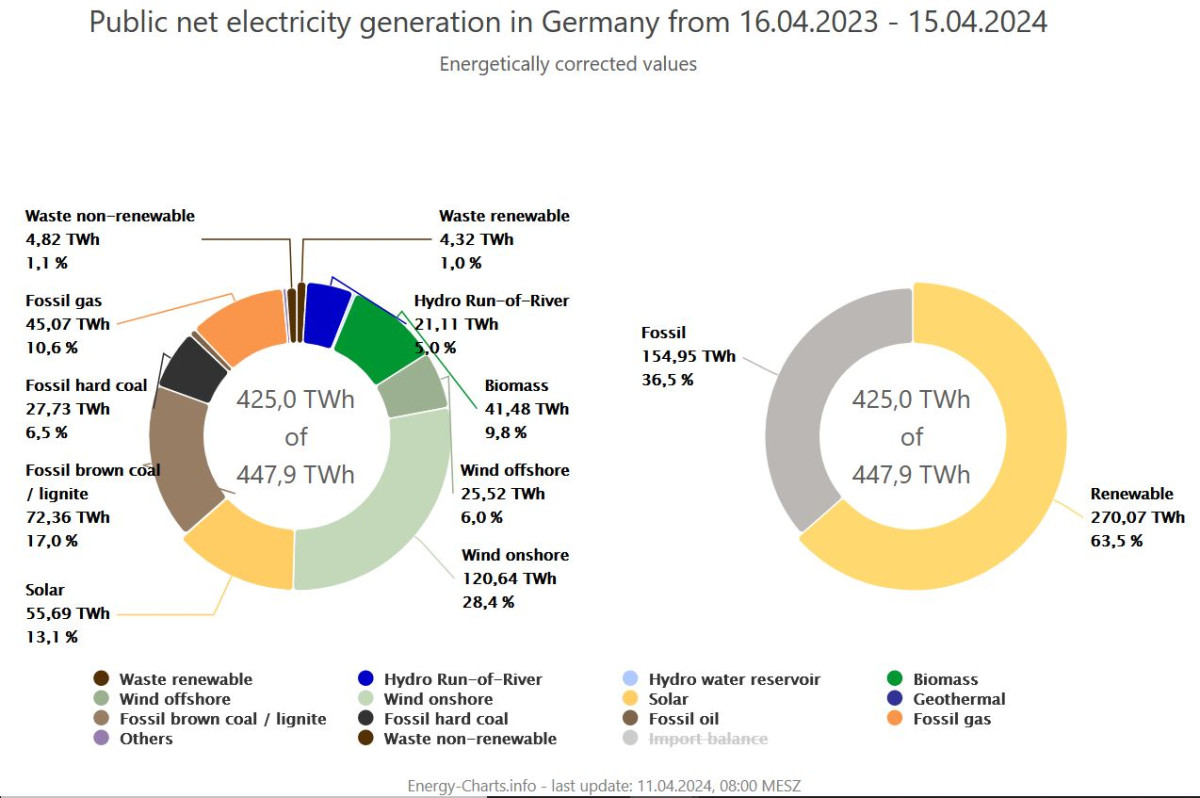

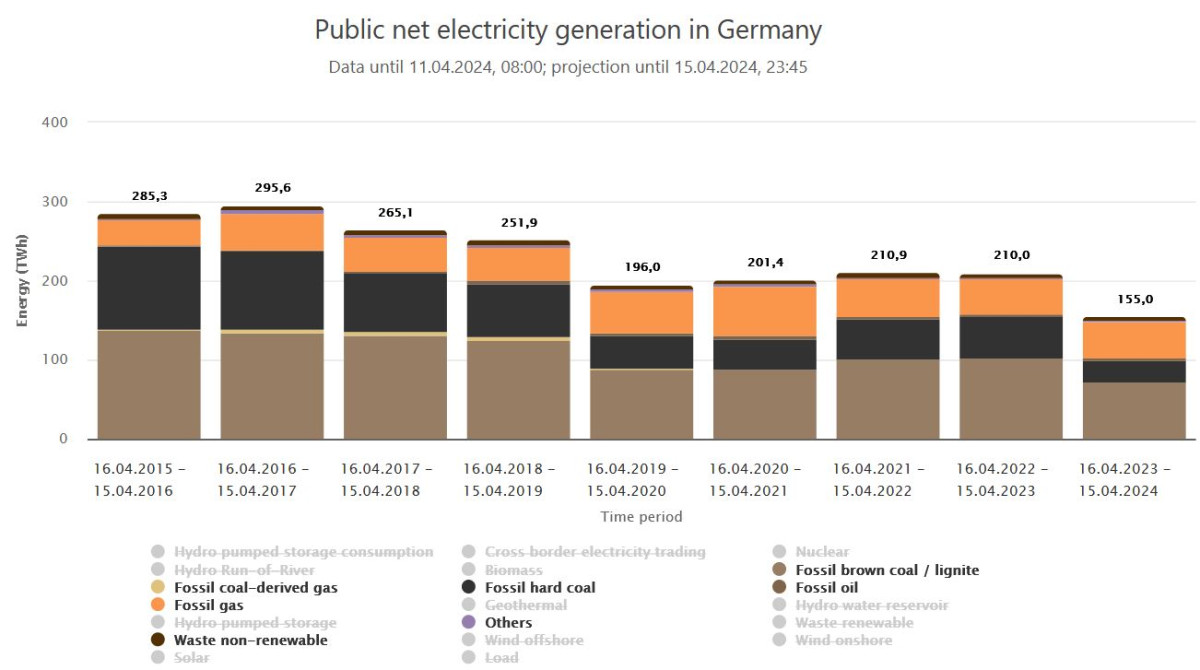

Nuclear power had a total output of just under 30 terawatt hours (TWh) in the year before the last three plants went offline and output dropped to zero. On the other hand, the output of renewables was 237 TWh in the period between April 2022 and the final phase-out step. In the year after 15 April 2023, renewables had surpassed the previous year’s output, reaching nearly 270 TWh by early April, according to Fraunhofer ISE researcher Burger. With a net increase of more than 30 TWh, the additional output of renewables alone thus more than compensated for the loss of nuclear capacity in net public electricity generation.

Fossil power sources contributed 210 TWh to electricity production in the final year of nuclear power use, when Germany had deployed additional coal power capacity as a safety measure in the energy crisis. However, the fossil fuel-fired power plants’ output dropped markedly in the following year and stood at about 160 TWh by 15 April 2024. In fact, the use of coal power dropped to its lowest level in more than half a century in the same year Germany went nuclear-free, meaning fossil fuel did not see a revival to fill the gap. According to an analysis by the anti-nuclear NGO Greenpeace, energy sector emissions in Germany dropped by 24 percent.

The total load in the electricity system decreased compared to the year before the phase-out, from 468 TWh to about 460 TWh, a trend that has partly been due to sluggish growth and lower energy demand from industry. However, as a result of renewables expansion, lower coal power use and reduced energy demand, Germany’s total emissions dropped by about 10 percent in the final year of the nuclear exit.

4) What changed in electricity imports and why?

For the first time in many years, Germany became a net electricity importer in 2023. The trade balance for electricity switched from 21 TWh of exports to 22 TWh of imports in the same period. Imports have risen despite sufficient plant capacity in Germany to cover domestic demand entirely. In March 2024, the country announced the shutdown of seven more coal-fired power plant units after the winter, as they are no longer needed to guarantee supply security. A Greenpeace analysis found that natural gas reserves alone would have sufficed to cover the demand for additional electricity in Germany. The fast growth of renewables meant that the country will likely become a net-exporter again roughly by 2030, the NGO said.

Economy minister Habeck stressed on the phase-out’s anniversary that Germany has enough power production capacity to fully cover its demand domestically, not least thanks to a resolute expansion of renewables. “At the same time, we participate in the European power market,” he added.

According to energy industry association BDEW, Germany's import balance is a sign of a functioning internal EU electricity market: it has been cheaper to generate electricity abroad in recent months and thus replace domestic fossil power generation. Lower power prices on European wholesale markets, driven by a high output of renewables from the Alps to Scandinavia especially during the summer of 2023, meant Germany’s coal power plants could not compete. Electricity retailers therefore opted for imports instead of more expensive domestic production. At the same time, the return of French nuclear plants to the grid, whose shutdown had pushed Germany’s electricity exports in the year before, meant demand abroad was also lower and the scope for power exports reduced.

While Germany’s electricity trade balance turned negative in 2023, imports accounted for only 2 percent of total electricity generation. One quarter of this share came from nuclear power frontrunner France, economy minister Habeck pointed out in early 2024. With the majority of imports coming from renewables-rich Scandinavia, French nuclear energy did not become more important for Germany’s power imports.

5) Did power prices go up due to the phase-out?

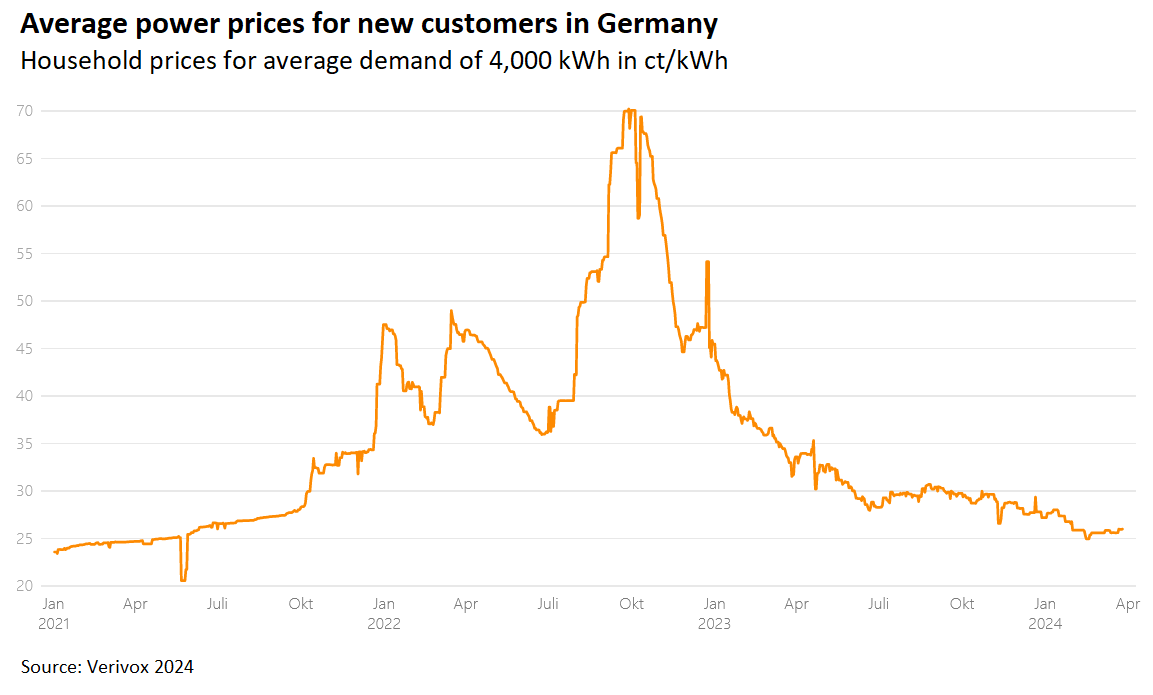

Day-ahead prices on the European power exchange in April 2024 stood at roughly 53 euros per megawatt hour (MWh), lower than in June 2021 (72€/MWh), at the onset of the energy crisis and before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In January 2021 was also 53€/MWh. Price decreases on wholesale markets also translated into lower power bills for households: New customers in March 2024 paid about as much as those entering contracts in June 2021 (roughly 25 cents per kilowatt hour), according to data by price comparison website Verivox.

Leaving the nuclear reactors online could have made wholesale power prices 0.3 ct/kWh cheaper in 2024, consultancy Prognos AG had estimated, which is equal to about one percent of the average household’s power bill. “That’s a magnitude which practically no one would recognize,” commented Prognos analyst Marco Wünsch.

The massive fluctuations on energy markets caused by fossil fuel prices at the height of the energy crisis made a clear attribution of the nuclear exit’s price effect difficult, according to an analysis by think tank Agora Energiewende. However, Agora said “the price-increasing factor of the nuclear exit has been overcompensated by the strong price reduction on the power exchange.”

Energy expert Thorsten Storck from Verivox likewise said falling wholesale power prices were the main reason customers had to pay less one year after the phase-out. “Fears that the nuclear exit could lead to a significantly higher price level for households have thus not come true,” he said.

However, energy expert Bolay from business association DIHK insisted that the decommissioning must have had an inevitable effect on power prices. “It’s clear that more supply to the market means lower prices for buyers,” he argued. German economy’s weakened output so far might have obscured the real impact: “Larger ramifications can be expected once the economy is back on track and power demand increases,” Bolay said. The DIHK pointed out that wholesale power prices in spring 2024 were still twice as high as they used to be in 2019, which was compounded by taxes, grid fees and other levies.

Efforts to further develop the power system and guarantee companies an electricity supply at competitive prices after phase-out have been inadequate, Bolay added. “Despite lower purchase prices, many companies pay more than in 2023” due to taxation and grid-related costs. Purchase prices could rise once economic activity picks up again, while further rises in grid fees are expected for the next years, Bolay warned. “Some relief regarding levies and fees is decisive for preventing competitive disadvantages from deepening.”

Government advisor Veronika Grimm, who sits on the national council of economic experts, also said that power prices “of course” would be lower if nuclear plants were kept running. In an interview with newspaper WirtschaftsWoche, Grimm argued that a “significant effect on the wholesale price” could be expected if the reactors still fed power into the grid, without specifying how much cheaper she thinks electricity would be. She singled out the Green Party for being “inflexible” with respect to the nuclear exit’s timing amid the energy crisis, criticising that the government went forward with the shutdown while simultaneously paying out huge subsidies to keep power prices affordable. Grimm recently released a study in which she argued that renewables will not make power prices more affordable in the next decade.

6) What happens with the retired nuclear plants and waste materials?

According to the World Nuclear Industry Status Report, 213 nuclear reactors had officially been decommissioned around the world by the beginning of 2024. However, dismantling had only been completed for 22 of these. In Germany, three nuclear reactors have been fully dismantled and 29 are currently in the decommissioning’s final stage, according to the Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management (BASE). Six research reactors and other three other nuclear energy-related installations continue to operate in the country.

Nuclear waste is currently kept in 16 temporary storage facilities that are needed as long as the search for a final repository is completed. This process was initially planned to be completed by 2031, but the deadline meanwhile has been postponed without setting a new date. “Only a deep geological storage offers permanent protection,“ BASE said. BGE, the federal company for radioactive waste disposal, has announced it will publish proposals for a possible location by 2027. “For all further steps, a realistic and ambitious schedule is needed that says until when a final repository is to be found,” a spokesperson for BASE told Clean Energy Wire.

The nuclear plant sites could also play a role in solving Germany’s power storage problems: PreussenElektra, operator of the decommissioned Brokdorf nuclear power plant in northern Germany that was taken offline at the end of 2021, wants to transform the site into a 800-megawatt (MW) battery plant. Coming with a price tag of about 500 million euros, the plant would be the biggest of its kind in Europe.

7) How did the national debate about nuclear power develop?

The nuclear exit’s completion in spring 2023 was accompanied by a reignited controversy about the phase-out’s timing during the crisis. Especially representatives from centre-right parties, the conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP), which under then-chancellor Angela Merkel decided to accelerate the original phase-out plan in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, moved on to question the phase-out or even called for re-entering the technology.

Partly fuelled by critical remarks from the International Energy Agency (IEA) about the step’s timeliness, nuclear energy has not disappeared from policy debates after the last reactors went offline. In a nod to the potential of nuclear technology beyond existing procedures, the research minister from the government coalition member FDP party promised a deepened commitment to develop nuclear fusion in Germany. Despite scepticism among former plant operators, the opposition party allinace CDU/CSU is pushing to include nuclear energy in long-term energy system planning again. In a motion in parliament, the conservative alliance in April 2024 called for a halt of dismantling works at the three decommissioned plants until a new government can make a final decision at a later stage. Environment minister Steffi Lemke commented that the idea to stop the decommissioning process for the last plants would be "detached from reality" and has little to do with the facts on nuclear power's usefulness in Germany's future energy system.

The CDU’s secretary general, Carsten Linnemann, ahead of the nuclear exit’s anniversary called the step an “historic mistake” that had led to all the negative consequences some had expected, such as higher imports, economic challenges and no countries following Germany’s example (In late 2023, the Spanish government confirmed its intention to end nuclear power use in the country by 2035 and to plan towards an energy system based on renewable power). However, Linnemann said the conservatives would aim to “correct” the phase-out. Meanwhile, local CSU politicians in the southern state of Bavaria have expressed concerns about the security of nuclear power stations planned in neighbouring Czechia.

Green Party minister Habeck pointed out that the government coalition merely implemented what a coalition of the FDP and CDU/CSU had decided in 2011. “It would therefore be better not to permanently put things into question that the whole country had agreed on but to focus on solving current problems.”

According to the nuclear safety agency BASE, a debate about re-entering nuclear power in the country lacks a technical foundation. Modern nuclear power plant concepts do not resolve the technology’s fundamental challenge of producing hazardous nuclear waste materials, a report commissioned by BASE found. “None of the alternative reactor types would make a final repository redundant,” the report led by the Institute for Applied Ecology (Öko-Institut) concluded.

Meanwhile, a plan agreed by France and Russia to produce nuclear fuel rods in Germany provoked an outcry among anti-nuclear groups in the country earlier in the year. Greenlighting modifications of the plant to construct the rods would amount to the "co-financing of the Russian war machine" and undermine Germany's nuclear phase-out, the NGOs argued.

Olaf Bandt, head of NGO Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND), commented that the debate about nuclear power posed a siginificant hurdle to climate action by directing investments away from renewable power and storage technologies. "No company would invest its own money into nuclear power plants, as this requires a lot of money and blindness to risks," Bandt argued. "Money for nuclear plants always came and will always will come from taxpayers."

However, many citizens in Gemrany so far do not seem to be convinced that nuclear power should no longer play a role: In a survey commissioned by Verivox ahead of the nuclear exit’s anniversary, more than 51 percent of respondents agreed with the statement that “the phase-out of nuclear power was a mistake.” Only about 28 percent fully backed the decision while 20 percent said they have no clear opinion. At the same time, just under 45 percent agreed with the statement that Germany should switch to a climate-neutral electricity supply as quickly as possible, while nearly 25 percent disagreed.

8) How did the nuclear debate move on in the rest of the world?

Many other countries continue to rely on nuclear technology or even plan to considerably expand it in a bid to bring down their energy-related greenhouse gas emissions. At the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) first ever nuclear energy summit in Brussels in March 2024, more than two dozen states called for a revival of the technology, including close allies of Germany such as France, the Netherlands, the U.S. and Japan. "Without the support of nuclear power, we have no chance to reach our climate targets on time," IEA chief Fatih Birol said at the nuclear summit.

The role of nuclear power in Europe’s emissions reduction plans has been a contentious issue for years, with Germany and France emerging as the main opposing forces between two groups of countries aiming to rely entirely on renewable power or to also use nuclear power in a future climate neutral energy system. France has the largest share of nuclear power production of any country but struggles to secure funding for new projects and to comply with cost and construction time plans for existing ones. The planned new Hinkley Point nuclear plant in the UK has faced years of delay and massive cost overruns. At an estimated 50 billion euros, the plant built by French energy company EDF looks set to become one of the most expensive buildings in history. Similar cost overruns could also occur with the planned new reactors in France.

While building new nuclear power plants remained an “unrealistic strategy for decarbonisation” due to the high cost overruns and long construction times, the current reactor fleet would also not be needed to achieve climate neutrality in Europe, according to an analysis by the NGO alliance European Environmental Bureau (EEB). “The existing nuclear fleet can be phased out alongside fossil fuels as EU countries transition to a drastically more efficient energy system,” the EEB argued. More renewable power in the system, lower energy use, and better flexibility through storage and demand-side management could compensate for the EU’s nuclear energy capacity, the NGO alliance said.

In early 2024, surging renewables and a slump in power prices were undermining operations of atomic plants, leading news agency Bloomberg to conclude that the industry is "facing some tough times ahead." The trend would be a "warning sign" that nuclear power could be pushed out of the market even if individual countries plan to huge investments.

Nuclear plants accounted for roughly 10 percent of Europe’s energy consumption in 2023, with France being the biggest user by far. Most reactors in the EU are approaching their 40-year runtime limit and will likely have to be shut down around 2030 unless they are granted runtime extensions. Globally, nuclear power accounted for about 9 percent of electricity production, down from more than 17 percent in 1996, the World Nuclear Industry Status Report found. In 2023, five new nuclear plants were connected to the grid, but total installed generation capacity still fell by 1 gigawatt (GW) due to parallel decommissioning. The increase in installed renewable power capacity was 107 GW in the same year.