Moorland restoration could play much bigger role in German emmissions reduction

Spiegel Online

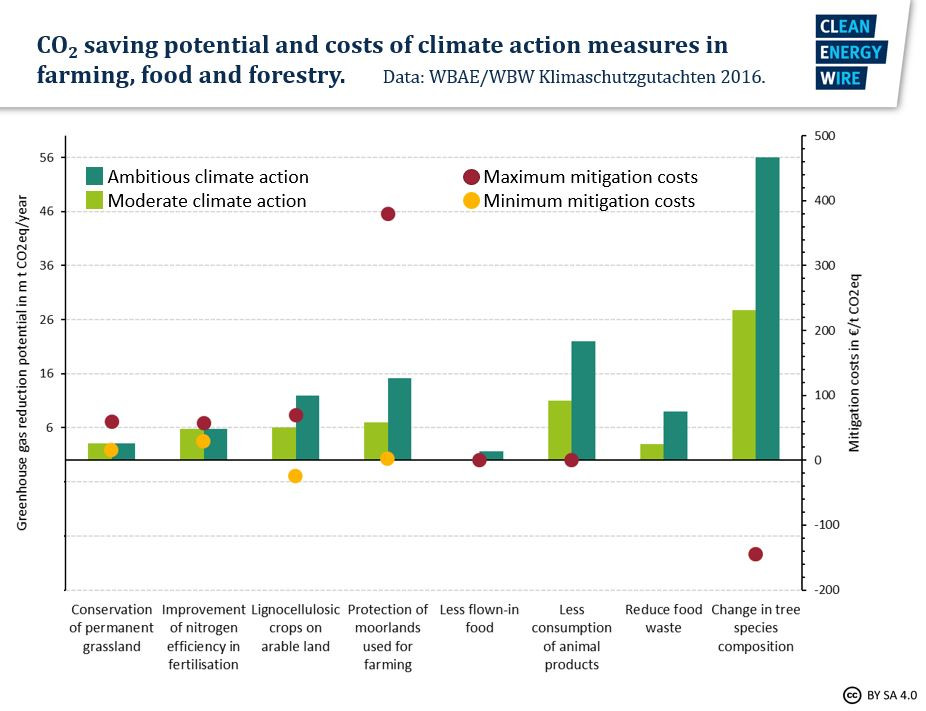

Drained moorland is considered a major climate issue in agriculture which causes at least as much CO₂ emissions as livestock farming, writes Susanne Götze in an article for Spiegel Online. Returned to its original state, it would be a massive carbon sink. “Moorlands are a time bomb – the longer they lay dry, the more CO₂ is released into the air,” Vera Luthardt from University for Sutainable Development Eberswalde told Götze. According to the article, the biggest hurdle for restoring moorland is regulation: Subsidies are given out for the wrong type of plants in the agriculture sector.

Peat soils cover about 4 percent of Germany and are its largest terrestrial carbon reservoir. A growing moorland takes up CO2 from the air and releases methane (CH4). Natural moors are largely climate neutral. If they are drained, however, oxygen enters the peat which leads to the release of CO2. Ninety-five percent of Germany’s moor soils are drained, mainly for agriculture. Although only 5 percent of Germany’s farmland uses moorlands, these drained areas release 50 percent of soil-related greenhouse gas emissions and 5 percent of Germany’s total emissions. Apart from preventing existing peatlands from being drained and farmed, drained areas could be restored and turned once more into carbon sinks, researchers and the Federal Environment Protection Agency (BfN) suggest. Another option, albeit with less carbon uptake potential, is the use of intensively used former peatlands as wetter, extensive grassland that could still be used as grazing grounds or for harvesting hay.