The stakes for energy and climate policy are high in EU elections

The campaign for the European Parliament is entering its final week, and climate protection is turning out to be a key issue for many voters, with young people taking to the streets and surveys showing it to be a major concern for the electorate across Europe.

In a recent poll of eight European countries, climate change ranked second among voters’ top concerns, just after immigration, which has dominated European politics for the last several years. Among German voters, climate change was the top issue.

Meanwhile, two very different groups are working to put climate change on the agenda. The Fridays for Future student movement is demanding more ambitious climate action, and wants to make it a focus of the European Parliament elections. At the same time, some far-right, Eurosceptic parties are rallying voters opposed to climate action, seizing on this as a potent issue as immigration has lost some of its urgency.

On a global level, European institutions have become key drivers of climate policy in recent years, taking on a major role in international climate negotiations as the US has stepped back, and setting binding emissions targets even as national governments like Germany have stalled in their climate efforts.

That means this year’s elections could shape climate and energy policy not only within the European Union’s 28 member states, but well beyond its borders, said Oldag Caspar of the environmental group Germanwatch.

“The EU is very important for solving the global climate crisis,” Caspar told Clean Energy Wire. “[It is] one of the most important players globally, maybe the most important one.”

The outcome this month could shape European climate policy for years to come.

Matthias Buck, an analyst at the think tank Agora Energiewende* said it’s hard to overstate the importance of European institutions when it comes to climate and energy policy. Individual member states cannot drive an energy transition alone, Buck said: “If we don't have a strong European policy framework on climate and energy, we are not going to make it.”

How do the European elections work?

In the European Union, legislation is made by three institutions. The European Commission is the EU’s executive arm, which proposes new laws and implements decisions. The European Parliament, the only directly-elected body, votes on legislation and passes the EU’s budget. It consists of representatives elected by the citizens of each member state. The European Council, made up of the executive heads of the 28 member states, represents the national governments. (You can find a handy two-minute explainer from the BBC here). The leadership of all three institutions will change hands this year.

May 23-26: European Parliament Elections

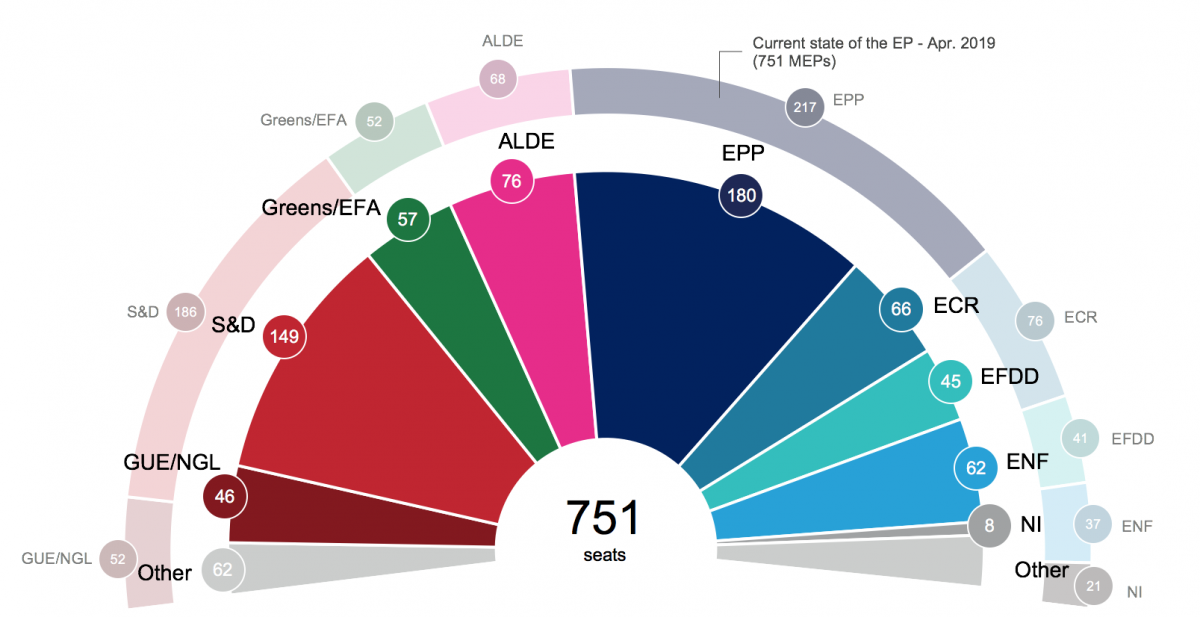

From 23 to 26 May, voters will elect the 751 members of the next European Parliament (MEPs). Those members will serve for five years, until 2024. (You can find the EU’s election website here and an explainer from the Financial Times here.) For now, that number includes representatives from the United Kingdom; if the UK leaves the EU, the number of seats in parliament will drop to 705.

Current projections suggest that the European Parliament’s two largest blocs, the centre-right European Peoples’ Party (EPP) – which includes Chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU coalition – and the centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), will likely lose seats to a range of smaller parties. Meanwhile, a suite of far-right, populist and eurosceptic parties - some of whom are also denying climate science - are expected to make significant gains. On the other side, Green candidates who strongly back climate action are on course for their best showing ever and could play a critical role in a more divided parliament.

In Germany, the Green Party is expected to double its support in the EU election. It also looks set to gain in German state and local elections taking place on the same day. Voters in the city-state of Bremen – Germany’s smallest state – will elect a new parliament. The Social Democrats (SPD), who govern currently in a coalition with the Greens, may come second for the first time since World War II, as polls indicate a slump for the SPD and a parallel increase for the conservative CDU. A severe loss may raise the pressure on the already battered SPD to sharpen its profile in the federal coalition with Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU, for example in current disputes about the climate action law or the plans to exit coal-fired power generation.

Citizens in eastern lignite-mining states will also vote in local elections. Results may provide clues for state elections in autumn, which are interesting from a climate and energy policy standpoint, as the region is pivotal in discussions about an exit from coal-fired power generation.

Will the EU elections change the dynamics on energy and climate policy?

What the new dynamic in Europe will mean for climate policy is unclear. A recent study from the Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe, an environmental NGO, found that the conservative EPP, the parliament’s largest bloc, regularly opposed what the group considered major climate and energy legislation. The centre-right bloc has “shown a complete lack of support for climate action,” the authors wrote (the centre-left S&D ranked comparatively higher).

Despite that, the European Parliament has historically been the most ambitious European institution when it comes to climate policy, said Annika Hedberg of the European Policy Centre, a Brussels-based think tank.

“The European Parliament has tended to be more ambitious than what the European Commission's proposals have been,” Hedberg said. “Despite what kind of party composition the European Parliament has had, it has tended to take very ambitious climate positions.”

But the rise of populist parties with platforms that explicitly oppose climate action could challenge that cross-party consensus, Hedberg said. “This is a serious risk in the election,” she said. “Will there be this politicisation on climate change?”

The new parliament will also have a say in selecting the new members of the European Commission. The European Council will nominate a candidate for president of the European Commission (an office currently held by Jean-Claude Juncker of Luxembourg), one of the most powerful positions in the European Union, along with 27 other commissioners. The president and commissioners must then be approved by a majority of MEPs. Separately, the European Council will elect a new president to replace outgoing president Donald Tusk of Poland.

Energy and climate policy contacts for journalists: European Elections 2019

Clean Energy Wire has compiled a list of contacts (click here) as a jumping-off point for journalists covering the 2019 European Parliament elections.

Under the current “Spitzenkandidat” or “lead candidate” system first used in 2014, the Council would nominate the candidate of the party that wins the most seats in the parliament. But some in the Council have said they will not be bound by that process, such as French President Emmanuel Macron.

Still, the Spitzenkandidaten nominees from the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D) are considered leading contenders to head the Commission, and both have expressed support for policies to combat climate change.

An analysis in Politico found that EPP candidate Manfred Weber of Germany has chosen to “downplay” climate change as an issue on the campaign trail. During a debate this month, Weber called the topic of climate change “existential”. But, he said, “As Europeans, we will not save the climate alone." Weber said he would focus on lobbying other countries to step up their commitments.

S&D’s Frans Timmermans of the Netherlands said he would make climate change a top priority and called for a CO2 tax. "The European Commission president has to become personally responsible for climate change," Timmermans said, according to Deutsche Welle.

His remarks are in line with demands by many NGOs and research institutions. “Climate change should become a core priority for the EU during the next five years and be addressed through all European policies, from the agricultural common policy to the cohesion or trade European policy,” said Nicolas Berghmans, research fellow at IDDRI, a European think tank based in Paris.

Which climate policies are decided at the EU level?

So how much climate policy is actually made at the EU level? The short answer is: a lot, and more each year. That’s because, within the European Union, everything from auto markets to power grids are increasingly connected across borders, said Agora’s Buck.

“In Europe, we have advanced very far in interlinking our economies,” Buck said. When it comes to climate and energy policy, “in Europe, you cannot do it alone,” he said. “You need to do it in a coordinated way.”

The EU has made major strides on this front. Over the past few years, the Parliament, Commission and Council have recently engaged in “a complete renovation” of the EU’s climate and energy laws, Buck said.

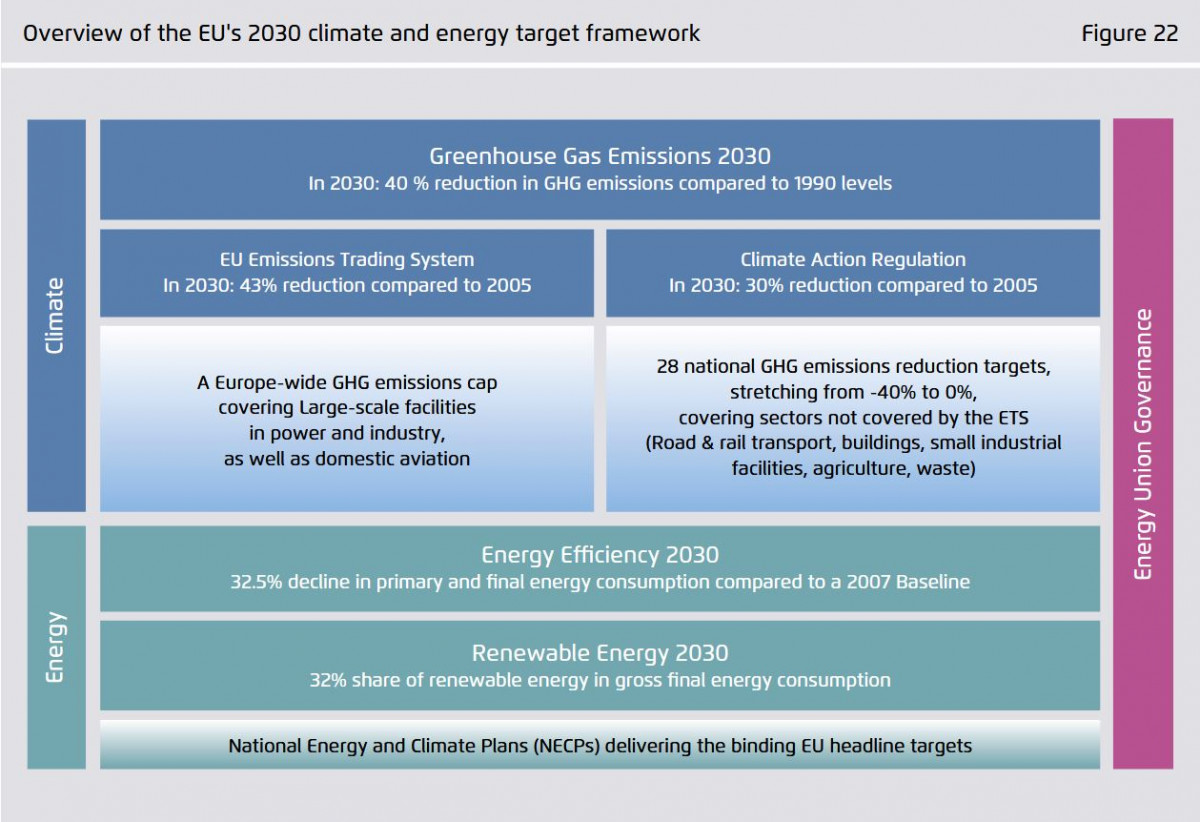

“We adopted, in the last two years, a comprehensive framework on how Europe will decarbonize the energy system by 2030,” he said.

That included reforming the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), which sets a cap on emissions from energy and heavy industry; new legally binding annual emissions targets for other sectors, including agriculture, transportation and buildings, under the EU’s “Effort-Sharing” legislation; and a major clean energy package covering renewable energy, efficiency, and electricity regulation.

According to IDDRI’s Berghmans, the big questions on the agenda right after the European elections are the revision of EU climate ambition for 2030 and for 2050, and the finalisation of the EU budget for the period 2021-2027.

The 2015 Paris Agreement requires nations to present planned efforts to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change (nationally determined contributions, NDCs), and to ratchet up those commitments over time. The next set of plans, including a long-term climate strategy, is due in 2020. In December 2018, the European Commission proposed a target of climate neutrality by 2050. It is now up to the national heads of state and government in the European Council to decide whether the Union should pursue this goal. If all leaders agree, they will then call on the Commission to propose the necessary long-term strategy, and the European Parliament will get a say in the adoption at that point. The current parliament already endorsed the objective of net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050 in a resolution in March 2019.

French president Emmanuel Macron has called for the EU to embrace the goal of carbon neutrality by 2050, while countries like Germany and Poland have so far resisted that target as too ambitious. However, after much pressure, Merkel announced that her new climate cabinet will debate how Germany could reach climate neutrality by mid-century. Should the ministers find a “sound” way to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, Germany would be able to join France’s initiative. "A rapid decision by the [European] Council in June would be a good signal," Berghmans told Clean Energy Wire.

These EU targets have major ramifications for member states. For instance, Germany is currently debating a highly controversial Climate Action Law and potential CO2 price — all in no small part to meet those EU targets.

“If we would not have Brussels, if we would not have the Brussels institutions, many countries would do a lot less on solving the climate crisis,” said Germanwatch’s Caspar.

Besides the major climate and energy legislation, much of the EU’s basic business has climate implications, said Hedberg, of the European Policy Centre.

If we would not have Brussels, if we would not have the Brussels institutions, many countries would do a lot less on solving the climate crisis.

One of the major tasks of the next European Parliament will be to pass a multi-year budget, which will set funding for a variety of climate and energy initiatives. And key policies like trade and agriculture are decided at the EU-level.

“This is huge,” Hedberg said. “This really depends on who's in the parliament, and how serious they are about the 2050 transition.”

Voters say climate change is a top issue - rivalling immigration

Surveys suggest that voters are more concerned about climate change than ever before. A poll of citizens in eight European countries just weeks before the election found that climate change ranked second among voters' top concerns, just behind the hot-button issue of immigration.

That finding echoed earlier surveys. A study commissioned by the European Parliament this spring found that 43 percent of respondents said climate change should be “discussed as a matter of priority” during the election campaign - ranking about even with immigration and the fight against terrorism. (The top two topics, named by about half of respondents, were “Economy and Growth” and “combatting youth employment.”)

In Germany, a long-term survey by the pollster Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, which asks respondents to name the country’s two “most important current problems,” found that “Environment/Energy Transition” topped the list for the first time in May, outranking “Foreigners/Integration/Refugees” among voters’ top concerns.

Why the sudden surge in interest? Matthias Jung, Forschungsgruppe Wahlen’s managing director, told the newspaper Tagesspiegel that, in Germany at least, the attention to climate change was likely driven by two things: an unusually hot, dry summer in 2018, and recent school strikes by students demanding more action on climate change.

“First, last summer created personal evidence for many people, even though cause and effect cannot be clearly linked in the weather,” Jung told Tagesspiegel. “Second, the protest movement 'Fridays for Future' is currently enormously present in the media.”

Competing pressures: Students demand rapid climate action, climate science deniers push back

The elections will also be a test of two very different messages on climate change.

For months, the “Fridays for Future” climate strikes have brought students to the streets across Europe to demand more action on climate change. In March, German activist Luisa Neubauer joined student organisers from across the continent, including Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, for a rally at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate and announced that the movement would focus on the European elections.

“Europe, we’re coming,” Neubauer declared. “We are going to make the European elections about the climate. We’re not letting borders separate us.”

The European elections could be the first real test of the movement’s political power, and a gauge of whether Fridays for Future can turn young people into voters. The students have announced a major global protest on the Friday during the elections (24 May).

But, at the same time, there is pushback from the right, as some right-wing populist parties see opportunities to rally voters on an anti-climate action platform, and are seizing on opposition to climate action. In Finland, the nationalist Finns Party made opposition to climate policy a centrepiece of their campaign in national elections this spring. In Germany, the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland, which originated as a eurosceptic party and rose to prominence by taking a hard line against immigration, is increasingly taking on opposition to climate action as a third major plank, the magazine Spiegel reported this spring.

“We would be foolish to not take up the subject,” Jörg Meuthen, currently the AfD’s sole MEP and the party’s lead candidate in the European elections, told Spiegel. “As a politician, you have to tackle the subjects people care about.”

A recent study from Berlin-based climate think-tank adelphi found that the majority of the continent’s right-wing populist or Eurosceptic parties can be viewed as disengaged or having inconsistent, sometimes ambiguous views, without openly rejecting climate science - such as the Italian LEGA. Several of the parties, however, reject either climate science or climate action - like the German AfD. With these parties expected to make major gains in the upcoming election, that could shift the conversation within the European Parliament, said Hedberg, of the European Policy Centre.

“We've already seen that in some member states it almost feels like the environment is becoming the new migration issue,” Hedberg said.

*Like the Clean Energy Wire, Agora Energiewende is a project funded by Stiftung Mercator and the European Climate Foundation.