The wicked task of feeding 83 million in a climate-friendly way

- Contents

- Emissions-cutting measures in the farming sector

- Could less meat and trade reduction be the solution?

- Cutting down on synthetic fertilisers

- Organic farming as a climate solution?

- Protecting grassland and moorlands

- Farming subsidies aren’t geared to preventing climate change

- CO2 reduction costs in agriculture and costs for adaptation

- Next steps

A record hot and dry summer in Europe in 2018 stoked public debates about tackling climate change, while taking a heavy toll on farmers. The German grain harvest is expected to be 19 percent lower than the average of the last three years, and many farmers are now questioning whether they can sustain their herds through the winter.

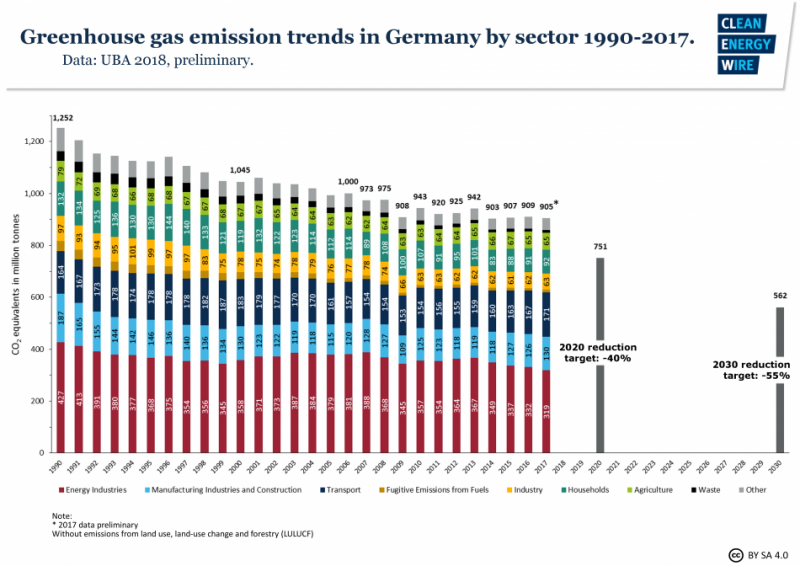

In August, farmers called for state compensation, but this brought the debate back to climate change – some critics wondered aloud if modern intensive farming and monocultures may be ill-suited for the extreme weather climate change will bring. They also noted that all sectors of the economy are being called upon to help fulfil Germany’s goal of near carbon neutrality by 2050, and that agriculture, which makes up 7 percent of Germany’s greenhouse gas, will have to change as well.

German agriculture minister Julia Klöckner came to the farmers defence. “The one thing we shouldn’t do in this situation is to tell farmers ‘you are to blame for climate change’,” she said in August. “Climate change is a global phenomenon. […] And farming is also part of the solution.”

In its Climate Action Plan 2050 the government expects the agriculture sector to reduce its annual 65 million tonnes of CO2 by 34-31 percent over 1990. Although a wholly emission-free farming sector will never be possible, Germany must find a way to make changes in this area to reach its goals and to comply with the Paris Climate Agreement.

But which measures will be most effective? The highly diverse sources of emissions in the sector and the competing emphasis on other environmental aspects of farming, such as biodiversity, make choices unclear. Changes that cut emissions in one area could end up creating emissions in another. Reducing livestock may lead to sourcing from abroad, for example, or turning arable land into grasslands may bring food scarcity in the future, if climate change reduces crop yields – a spectre raised by last summer’s heat wave.

Global emissions from farming make up 11 percent of total emissions. This is similar in many developed countries, with 9 percent in the United States (2016) and as high as 17 percent (2017) in France, which boasts Europe’s largest farming sector. Both the US and France have seen rising or stable farming emissions since 1990, while Germany’s have decreased by almost 18 percent, due mainly to the closure of many farms in eastern Germany after reunification.

“Compared to the energy or industry sectors, emissions from agriculture are small – which doesn’t mean we cannot still get better,” Klöckner, a member of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Party (CDU), said in August.

But a broader view of the food supply chain shows a different picture. The typical diet of one German creates around 1.75 tonnes of CO2 per person a year, almost as high as transportation emissions, the environment ministry says. Emissions from the food supply chain (including farming of crops and animals (in Germany and abroad), fertiliser production, transport of goods, food retail and food preparation equal 25 percent of Germany’s total greenhouse gas emissions, although they are not all emitted in Germany, the Scientific Advisory Board on Agricultural Policy, Food and Consumer Health Protection (WBAE) and the Scientific Advisory Board on Forest Policy (WBW) have calculated.

Emissions-cutting measures in the farming sector

Concrete measures to fulfil emissions-reduction targets are chronically difficult to pin down in the farming industry. This is partially due to the sector’s very diverse emissions – from animal husbandry, arable soils, moorlands and the use of mineral fertilisers, to name just some major sources of greenhouse gases. In addition, other farming issues tend to eclipse agriculture emissions in the public debate – such as such as heavy use of single crops, or monocultures, and the loss of biodiversity.

The European Union’s Greening measures introduced in 2014 (e.g. crop diversification, fallow land, buffer strips, catch crops, maintaining permanent grasslands), alongside organic farming methods, are mainly aimed at protecting natural resources and biodiversity and improving conditions in livestock farming. Almost as an afterthought, they are automatically understood to also be “good for the climate”, although the whole system of farming subsidies is not at all coherent with either climate or environmental protection targets, Angelika Lischka, consultant for agriculture policy at the Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU), says.

"When some greening measures were defined at European level, the focus was on controllability rather than practicability."

The German Farmers‘ Association (Deutscher Bauernverband – DBV) says the environmental measures in EU farming policies “could have achieved more”. “But red tape and a lack of flexibility and tolerance for agricultural enterprises have made the application of certain greening measures impossible". "When some greening measures were defined at European level, the focus was on controllability rather than practicability," according to Steffen Pingen head of the environment department at the DBV.

The idea of using the same measures to simultaneously protect natural resources and mitigate climate change may seem like the perfect solution. But a closer look reveals trade-offs and conflicting interests.

While environmentalists and climate activists want changes to Germany’s meat production and export practices, a stop to large-scale soy bean imports and more organic farming, conventional farmers and government advisors maintain that only intensive farming practices produce food with a smaller carbon footprint. Reducing production in Germany, they say, would not be beneficial to a growing global population or would simply lead to moving production abroad (carbon leakage).

Another bone of contention is the climate impact of bioenergy. Farmers highlight the CO2 savings from the increased cultivation of crops used to generate electricity, claiming this contributes to curbing climate change. Germany has some 9,000 biogas plants, typically operated by farmers and covering 7 percent of Germany’s power generation. Many environmental and climate activists, on the other hand, dispute its positive climate effects (depending on the kind of energy crop and where it is produced) and criticise monocultures and land consumption for non-edible crops. The government, seeing the increased conflict over land for food crops, grassland or energy plants, put a stop to any further increase in power generation from biogas in 2016.

Could less meat and trade reduction be the solution?

37.5 percent (24.5 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents in 2016) of agricultural emissions come directly from methane emissions of animals farmed in Germany, mostly from cattle and dairy cows. Other livestock such as swine and poultry don’t emit as much directly (unlike cows, they aren’t ruminants and don’t emit much methane), but they cause emissions through land-use for feeding, barn emissions and manure.

Environmentalists would like to downsize the livestock sector in Germany, ideally in combination with higher prices for meat and fewer exports. Last summer’s heat wave that severely curtailed the hay and maize harvest led farmers to consider reducing their herds, a move welcomed by environmentalists.

(See a CLEW article on meat consumption and agri-food exports here.)

Indeed, meat consumption is declining in Germany, providing another argument for raising less livestock. But neither the government nor farmer’s associations have made the step towards advocating a more vegetarian diet. “It is not a successful strategy to patronise German consumers and tell them to change their preferences when it comes to meat-eating,” Steffen Pingen, head of the environment department at the DBV says. “We are pursuing the goal of producing agricultural products as climate-efficiently as possible."

The Climate Action Plan 2050, which doesn’t mention reducing cattle numbers, foresees lower emissions from livestock farming mainly through efficiency gains and voluntary best practice rules on how to feed and keep cows and cattle, the farmers say.

In the meantime, German farmers produce more meat than people in the country can eat. The overall self-supply with beef in Germany is on average 108 percent (2013-2015), 118 percent for pork and 125 percent for milk products.

Climate activists at Germanwatch point not only to the domestic consumption of meat and dairy but also to the large exports of animal products from Germany and related imports of fodder like soy beans as large emitters of greenhouse gases.

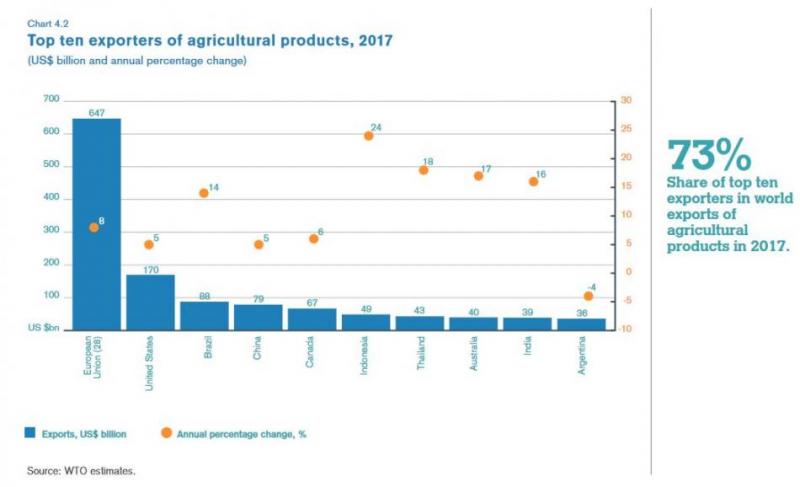

Germany is both the world’s third-largest exporter and importer of agriculture products, according to 2015 WTO figures. Since 2000, exports and imports have grown continuously. One third of Germany’s farming products are exported. The ministry for agriculture pursues a pro-export strategy, supported with 8.8 million euros in 2017.

According to calculations by consultancies adelphi and systain, Germany is now using some 22 million hectares of land globally for its food retail trade.

Around 27 percent of the raw protein needed for German farm animals is covered by soy bean products, of which 75 percent are imported, mostly from South America, the agriculture ministry reports. Between 1997 and 2018, global land use for growing soy beans has nearly doubled. In 2010 Germany was using some 6.4 million hectares of soybeans abroad, out of 130 million worldwide, to feed its livestock.

Steffen Pingen at the German farmers’ association says no German farmer specifically produces to export – but that since the world market for farming products was determining prices, they still had to be competitive there. Since more efficient farming methods can reduce emissions per food unit, farmers in Germany argue that it is beneficial for the climate if everything is produced where it thrives best, i.e. where natural conditions are favourable. “That is why wheat should be grown in Germany and soy beans in South America,” Pingen said, a view that is backed by the agriculture ministry in this report.

Harald Grethe, professor for International Agricultural Trade and Development at the Humboldt University Berlin and chairman of the WBAE, pointed out that the food that Germany no longer exports has to be grown elsewhere, which could result in higher emissions overall if done on grasslands, savannah or former forest areas. “But of course if Germans were to change to a more sustainable diet, it would be possible to farm the existing arable land less intensively and therefore in a more climate friendly manner.”

(For more on emissions from animal farming and food exports, see this CLEW article.)

Cutting down on synthetic fertilisers

Arable soils are the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in Germany’s agriculture sector. They emit around 26 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents (40%) of laughing gas (N2O) per year, mostly due to the use of synthetic fertilisers. Laughing gas is 300 times more harmful to the climate than CO2.

Reinhild Benning, Senior Advisor for Agriculture and Livestock at Germanwatch, says that a solution would be to grow more leguminous plants at home, such as beans, trefoil-grass, or lupines, which are classic protein sources. Substituting soy bean imports would not only cut down freight emissions and help preserve forests and savannahs in South America, but also reduce the need for synthetic fertilisers because of their natural nitrogen-fixing abilities.

The WBAE says limiting synthetic fertilisers (nitrogen) could curb annual emissions by 5.8 million CO2 equivalents (out of the 65 million tonnes coming from the farming sector). This could be achieved by improving production technologies, better planning fertiliser use and optimising farming methods to reach similar harvests with less fertiliser.

Leguminous plants however, which receive 6 million euros per year as part of the government’s “protein plant strategy”, only help prevent global warming if they don’t replace more productive plants like maize or wheat, the WBAE report finds.

When it comes to limiting synthetic nitrogen fertiliser use, Germany is not adhering to its own N2O reduction targets. By 2010 the nitrogen surplus should have been reduced to 80 kg of nitrogen per hectare (kg/ha), but has been closer to 100 kg/ha or higher in recent years. The 2030 target is 70 kg/ha. “The latest reform of the fertiliser law is not ambitious enough,” says Benning from Germanwatch. "Climate and water protection seem not as important to the government as meat and milk exports."

Organic farmers who uses legumes, intercropping and more frequent crop rotation because synthetic fertilisers are not allowed, say their way of farming is far more climate friendly, also with regard to laughing gas emissions and other soil emissions.

Organic farming as a climate solution?

The German government has set the 2030 target to farming 20 percent of arable land organically. In 2016, the share stood at 7.5 percent. With revenues of 9.48 billion euros in 2016, Germany is the largest market for organic food in Europe, however its market share is still only 4 percent.

Organic farmers apply a more varied crop rotation and herbicides, pesticides and artificial fertilisers are forbidden. More gentle ploughing methods and crop choices help to build up a humus layer in the soil which is known to be a carbon sink.

The “4 per 1000” initiative, which Germany joined at the 2015 UN Climate Summit in Paris, aims to increase the soil carbon stocks by 4 percent every year in order to offset the increase of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Because of their sustainable approach, organic farms emit much less greenhouse gas than conventional farming operations, Benning from Germanwatch says.

But government advisors from the WBAE say this is only partially true. While a reduced use of mineral fertiliser, more leguminous plants in the crop rotation, smaller herds and grassland protection through outdoor animal husbandry usually lead to considerably lower emissions per hectare, the carbon footprint of organic produce isn’t always smaller.

As organic farmers produce less crops and meat per hectare, only those farms with a high share of leguminous plants and 80 percent of the yields of conventional farms actually achieve smaller carbon footprints, the scientists write. As a rule, “organic farming cannot be recommended as a climate protection measure”, they conclude.

However, in the same year as the WBAE report, the environment ministry published advice showing organic food generally has a smaller carbon footprint.

The WWF, on the other hand, lists studies that show making farming in the EU 100-percent organic would reduce emissions from this sector by 35 percent. Combined with gentle ploughing techniques, organic farming could turn soils in Germany from a net emitter to a net sink for carbon, the organisation says.

Organic farms have around 25 percent smaller yields than conventional farms. The farmers’ association sees this as another reason why expanding organic farming for climate purposes isn’t the way to go.

“If we don’t lower our food consumption, this would mean that having only organic farms would require 20 to 30 percent more land to grow the same amount of food. This use of more land would lead to more greenhouse gas emissions,” the WBAE’s Grethe explains.

Protecting grassland and moorlands

But even the WBAE says that grasslands, which can store up to 50 percent more CO2 than farmed fields, are often better preserved by organic farmers who use it to graze their animals and harvest their own fodder, in particular trefoil-grass.

Instead of protecting this valuable carbon sink, since 1991 Germany has lost over 600,000 hectares of grassland, mainly due to an increased demand for bioenergy (biogas and biofuels) and fodder plants like maize and rapeseed. This has led to annual greenhouse gas emissions of 2.5-3.1 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents, according to the WBAE.

Farmers see the increased cultivation of energy crops and their use to generate electricity as a contribution to climate action. The government however, seeing the increased conflict over land for food crops, grassland or energy plants, put a stop to any further increase in power generation from biogas in 2016.

In order to reduce the competition for land between solar panels and crop fields, large ground-mounted systems may generally only be installed on land that is not suitable for arable farming.

(See a CLEW dossier on bioenergy in Germany here.)

Once lost, it is difficult to restore grassland sinks because it can take up to 200 years to restore the CO2-rich humus layer. The most climate-relevant move would therefore be to protect the remaining grasslands, the WBAE concludes.

Although the surface area of grassland has grown a little since 2013, environmentalists say that German and European farming subsidies are not helping the problem. In a bid to protect the remaining grassland, Brussels introduced a ban on turning any permanent grassland into croplands. Grassland is considered permanent if it has not been part of a farm’s crop rotation for five years or more – a reason for even environmentally aware farmers to plough their pastures every five years. “From a climate point of view this is completely insane. But how am I supposed to explain to my grandchildren that I basically lost arable land that they might need in the future to the permanent grassland status?” asks organic farmer and Green Party MP Friedrich Ostendorff.

Obviously farmers would want compensation for allowing land to undergo substantial cultivation restrictions, Grethe said. But even under existing rules, Germany could use the EU farming subsidies to introduce measures such as a “grazing premium”, which would reward farmers for using their pastures for animal grazing, thereby protecting these areas, he said.

A very similar issue affects moors and peatlands. Dry peat releases carbon and although only 5 percent of Germany’s farmland uses moorlands, these drained areas release 50 percent of soil-related greenhouse gas emissions and 5 percent of Germany’s total emissions.

Apart from preventing existing peatlands to be drained and farmed, drained areas could be restored and turned once more into carbon sinks, researchers and the Federal Environment Protection Agency (BfN) suggest. Another option, albeit with less carbon uptake potential, is the use of intensively used former peatlands as wetter, extensive grassland that could still be used as grazing grounds or for harvesting hay.

But the competition for land is high. “Limiting the amount of land farmers can cultivate by requiring a switch to extensive farming, moorland restoration or conversion into permanent grassland, definitely means losses for the farmer and even amounts to dispossession,” Pingen of the DBV says. In addition, farmers say this could lead to carbon leakage issues – if less food is produced in Germany, production will move abroad instead and potentially cause higher emissions.

One compromise could be to thoroughly protect existing moorlands and only partially restore former peat lands so they are still usable as pastures.

Farming subsidies aren’t geared to preventing climate change

Climate friendly farming methods are available for livestock keeping, crop cultivation and on peat soils and grasslands. But Germany’s farmers are rarely obliged to comply with these best practices. In the absence of rules or incentives specifically geared towards running a climate friendly operation, their main concern is economic well-being, or in many cases simply the survival of their farm.

To conventional farmers, every new “greening” rule, every new obligation to improve animal welfare or be more conservative fertiliser use means a possible cut in income, be it through different land-use, mandatory investments or more time-consuming procedures.

Farmers lament the bureaucracy of environmental protection and the fact that there are few rewards and instead only compensation for losses for such measures, Angelika Lischka at NABU says.

Around 38 percent of the European Union’s budget is used to subsides the agriculture sector in Europe. In 2016, every German farm received on average 15,300 euros in subsidies, depending on how much land they own. A small number of large farms (14.5%) received over 60 percent of the total direct payments.

Both the EU and the German government maintain that this is necessary to ensure that Europe produces enough food for its population and doesn’t become reliant on imports.

Both also say that “public money should be used for public goods”, meaning that the subsidies should be used to benefit the whole of society, through healthy food and an ecologically balanced and climate-friendly environment.

Greening rules were recently added to the complex subsidy allocation system that is the EU’s 58.8-billion-euro (2018) Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Since 2014, 30 percent of area-based subsidies under the CAP have been tied to compulsory measures such as diversifying crops, maintaining permanent grasslands or dedicating five percent of arable land as “ecological focus areas”. However, not only can farmers opt for the easiest and least effective measures, an evaluation of greening policies shows that the resulting environmental and climate protection effects have been minimal.

“A large share of these subsidies is flat rate and non-targeted. Germany uses some five billion euros in EU subsidies simply as direct payments to farmers according to how much land they farm,” Grethe says.

If subsidies flow to large recipients who produce meat for export purposes, if they use imported fodder like soy beans from Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay, where former carbon sinks like forests or savannahs were turned into fields, then these million-dollar subsidies are lacking for farms that ensure, animal welfare and climate protection with fewer animals and regional fodder, Reinhild Benning from Germanwatch says.

The idea that all payments should be rewards for environmental, climate and other societal services would have to take hold much more deeply, in order to reform the system, Grethe said.

CO2 reduction costs in agriculture and costs for adaptation

Protecting or restoring moorlands and grasslands are two of the most effective but also the most expensive emission-saving measures in the agriculture sector. Reducing the use of mineral fertiliser doesn’t come cheap either, WBAE researchers calculate, but other efforts, especially those related to changing eating habits, could be cost-neutral or even save consumers money.

Meanwhile, a changing climate can also create costs, in particular through more frequent extreme weather events. Germany is projected to retain a benign and favourable climate or even better conditions for some plants due to rising average temperatures.

But in the summer of 2003 German farmers reported losses of 600 million euros due to drought, and a repeat in 2018, for which they requested a billion euros in compensation, show that drought resilience may be limited in Germany. In other years, too much rain has caused problems.

The same recipes that reduce agriculture emissions could make farmers more resilient, both the NABU and professor Frank Ewert from the Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF) say. “When cultivating a greater variety of crops, farmers will always have some crops that better withstand extreme weather than others,” Ewert said in an interview.

Keeping fewer animals and raising prices to a fair level would also help minimise the risk of extreme weather effects, NABU president Olaf Tschimpke said in a press release.

Other adaptation measures could be the introduction of (drip) irrigation to counteract decreasing amounts of rain in the summer months (ca. minus 21 percent by 2100), gentle soil cultivation methods or new, heat-resistant crops. However, all are likely to bring investment and/or operating costs and may not achieve sufficiently higher or stable harvests, a study for the German Environment Agency (UBA) found in 2012.

Next steps

Since the majority of farming subsidies and rules are decided by the EU, all eyes will be on Brussels in the next two years, where the 365-billion-euro budget for the next CAP funding period of 2021-2027 will be decided. After the lacklustre performance of the last greening policies, the European Commission’s June 2018 proposition mentions a “new system of “conditionality” [that] will link all farmers’ income support to the application of environment- and climate-friendly farming practices”. Through this, 40 percent of the CAP’s overall budget “is expected to contribute to climate action”, the paper says.

“Unfortunately, no one knows what this 40 percent target actually means or how it has been calculated,” Angelika Lischka from NABU told the Clean Energy Wire, an assessment that is shared by the farmers’ association.

Germanwatch’s Benning fears the worst and hopes for the best. “Agriculture commissioner Phil Hogan basically says that every country may choose itself what kind of climate action measures it will pursue. But setting targets without explicitly tying every euro to a specific climate service has failed,” she says.

Both Germanwatch and NABU have published their new CAP proposals, calling for strict conditionality of subsidies and climate action in farming but also for incentives (payments) to farmers who choose ecologically favourable methods (e.g. Agri-Nature Payments or ANP).

While participating in the CAP reform process at EU level, the German government has its domestic work in agriculture and climate policy cut out. In autumn 2019 the agriculture minister wants to present a new arable farming strategy; by 2021 the government wants to present a holistic strategy on how to reduce emissions from animal farming in Germany. And as a sector featuring in the Climate Action Plan 2050, agriculture will also have to be included in the climate protection law, due to be passed in 2019.

Rattled by the summer’s drought, farmer Friedrich Ostendorff senses that his colleagues are deeply concerned about the extreme weather. “The only good thing to come from this is that farmers talk to each other more again – simply because they don’t know what to do,” he told the Clean Energy Wire.

WBAE’s Grethe says: “Farmers’ willingness to operate in a more climate friendly way is high – if politicians provide for the necessary rules and rewards.”

At the end of August 2018 agriculture minister Julia Klöckner declared the summer’s drought a “weather event of a national scale”. “Climate change is here,” she said at a press conference where she offered 340 million euros in compensation to 10,000 farms whose existence is endangered. The reason: “Farmers, who literally produce the means for our survival, are not just any sector.”