EU’s Farm to Fork strategy impacts climate, productivity, and trade

What is the Farm to Fork strategy of the EU and what are its targets?

The European Union aims to become climate-neutral by 2050. The political agenda that is to shape the requisite transformation is the European Green Deal, and the Farm to Fork (F2F) and Biodiversity strategies are parts of it. Published in May 2020, the F2F strategy outlines how the EU wants to overhaul the food system to make it “fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly.” This future “farm to fork” food system would incorporate primary production (farming), the supply (value) chain and consumption. It shall have a neutral or positive environmental impact, help mitigate climate change, adapt to its impacts and reverse the loss of biodiversity, the European Commission has said.

Its specific targets for 2030 include reducing the use and risk of chemical pesticides by 50 percent; cutting nutrient losses by 50 percent; lowering fertiliser use by 20 percent; and increasing the share of agricultural land under organic farming to at least 25 percent (see overview below).

What is going to follow from the Farm to Fork strategy?

Europe’s Farm to Fork strategy is not a specific legislative proposal in itself but an outline of new premises for the future food system. This is also the reason why there exists no impact assessment and no public consultation on it.

The strategy sets out an action plan for non-legislative initiatives, amendments to existing legislation and new legislation, which will be submitted to the usual impact assessment and consultation process, followed by the bloc’s legislative process.

The targets and actions specified in the F2F strategy are assigned to four clusters: sustainable food production; sustainable food processing and distribution; sustainable food consumption; and food loss and waste prevention.

By 2023, the European Commission will present a proposal for a “legislative framework for sustainable food systems” that will aim to promote policy coherence at EU and national levels, meaning it will set common definitions and requirements for all actors in the food system. There are around 37 different measures in the strategy, ranging from avoiding “marketing campaigns advertising meat at very low prices” or “support reducing dependence on long-haul transportation [of food]” to developing an integrated nutrient management action plan to address nutrient pollution at source and increase the sustainability of the livestock sector.

Among the 26 measures to be tackled by 2024 are:

- Initiative to reward farming practices that remove CO2 from the atmosphere (by Q3 2021), i.e. develop a regulatory framework for certifying carbon removals based on robust and transparent carbon accounting

- Facilitate the placing on the market of sustainable and innovative feed additives; reduce the dependency on critical feed materials (e.g. soya grown on deforested land) by fostering EU-grown plant proteins - Proposal for a revision of the Feed Additives Regulation to reduce the environmental impact of livestock farming (Q4 2021)

- Legislative proposal and other measures to avoid or minimise the placing of products associated with deforestation or forest degradation on the EU market (in 2021)

- Recommendations to each member state on the nine objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) to be included in their strategic plans

- Clarification of the competition rules and monitoring the implementation of the unfair trading practices (UTPs) directive

- Action plan for integrated nutrient management to reduce pollution from fertilisers (2021)

- Action plan for the organic sector for 2021-2026 to stimulate supply and demand for organic products (2020)

- Proposal for a Farm Sustainability Data Network (data and advice on sustainable farming practices) (2022)

- Proposal for a revision of the existing animal welfare legislation, including on transport and slaughter (2023)

- Legislative initiatives to enhance the cooperation of primary producers (support position in food chain) (2021-2022)

- Using the new methodology for measuring food waste and the data expected from Member States in 2022 to set a baseline and propose legally binding targets to reduce food waste across the EU.

The full list of actions planned under the F2F strategy is available here. Researchers have criticised that “many of the strategy’s promises are not translated into action points.”

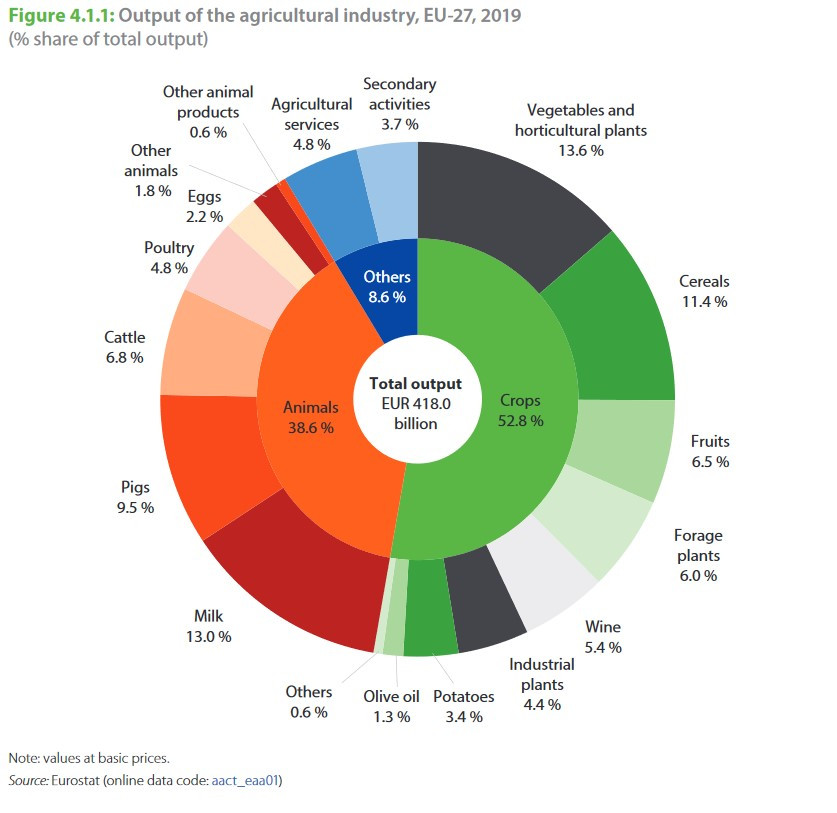

Info-Box: Europe’s agriculture sector and farming output at a glance

There are around 10 million farms in the EU, farming on 156.7 million hectares (about 38% of the EU’s total land area), 13 million hectares of which were used for organic farming in 2018. Two thirds of the EU’s farms are less than 5 hectares in size. These very small and small farms produced only 4.6% of the bloc’s total agricultural economic output while the 278,000 largest farms were responsible for 54.4% of total agricultural economic output (all data from Eurostat 2020/2016). The EU‘s agricultural industry created (gross) value added of 181.5 billion euros in 2019, 1.3% of the EU‘s GDP that year. The value of everything that the EU’s agricultural industry produced in 2019 was an estimated 418 billion euros.

The main produce of EU farmers are cereal grains (299.3 million tonnes in 2019), more than half of it is wheat, followed by maize, barley. The bloc produced 158.2 million tonnes of milk and 43.5 million tonnes of meat, half of it from pigs in 2019; as well as root crops (potatoes, sugar beets), vegetables and fruit. The EU’s cereals are mostly used for animal feed (nearly two thirds); one third is directed at human consumption, 3% is used for biofuels. The population of livestock in 2019 were 143 million pigs, 77 million bovine animals and 74 million sheep and goats, all of which have decreased between 2018-2019.

The EU cultivates three types of oilseed crop; the main two are rape and turnip rape, and sunflower, and soya is increasingly grown – oilseed output has decreased between 2018-2019. The EU harvested an estimated 29.5 million tonnes of oilseeds in 2019, which was about 2.5 million tonnes less than in 2018.

The consumption volume of mineral fertilisers, nitrogen and phosphorusby agriculture remained high in the period 2007 to 2018; an estimated 11.3 million tonnes were used in 2018. The gross nitrogen (N) balance for the EU-27 decreased from an estimated average of 51 kg N per hectare per year in the period 2004-2006 to 47 kg N per hectare per year in the period 2013-2015. Mineral fertilisers accounted for 45% of the nitrogen input in the EU in 2014, manure accounting for another 38%.

What are the implications for the climate?

To achieve the EU’s goal of climate neutrality by 2050, all sectors will have to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as much as possible. To this end, specific policy instruments and emission caps are in place in most sectors (e.g. emission cap-and-trade system for energy, industry; emission limits for vehicle fleets). The agriculture sector is included in the EU’s overall greenhouse gas reduction obligations for member states (effort-sharing). Although it is the only major farm sector worldwide to have reduced its greenhouse gas emissions (by 20%) since 1990, it still accounts for about 10 percent of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions (of which 70% are due to animals). “Together with manufacturing, processing, packaging and transportation, the food sector is one the main drivers of climate change,” the European Parliament stated in 2020. The farming sector’s emissions have hardly gone down in the past decade and are projected (with current measures in place) to stagnate in the decade to come.

. Source: [European Environment Agency 2018](https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/trends-and-projections-in-europe-2018-climate-and-energy).](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/ghg-emission-trends-and-projections-effort-sharing-1990-2030-eea_0.jpg?itok=mVGPer09)

The Farm to Fork strategy aims to accelerate the transition to a sustainable food system that helps mitigate climate change. Even if some of its targets, e.g. reducing antimicrobial sales, are not directly related to climate action, emission reduction has to be achieved in all areas of the value chain, i.e. in the growing, storing, processing, packaging, transporting, eating and discarding of food. Parts of the F2F strategy – such as rewarding farmers for removing CO2 from the atmosphere, rules for imports associated with deforestation – are primarily aimed at reducing emissions; while others should incur emission reductions even if their main objectives lie elsewhere, e.g. higher animal welfare standards (leading to fewer animals overall), larger organic farming areas (should increase carbon stored in soil) , more power to small farmers vis-à-vis large food trading and processing companies, reducing food waste and changing consumer eating habits (of meat).

The major challenge in decarbonising the food system lies in the many trade-offs that occur between the measures that aim to individually protect the environment, farm animals, consumers and the climate but fail to achieve all of these goals at once. Achievements in the social and economic sphere (affordable and healthy food, cutting red tape for farmers) may counteract the environmental objectives. Another example: policy actions promoting grass-based ruminant diets help reduce the use of human-edible biomass in animal feed and scale back intensive farming on grasslands but they also result in higher greenhouse gas emissions from the animals. On a more general level, critics of F2F have said that less fertiliser input and farming more land organically will reduce the EU’s food production, which will be compensated by less environment-friendly farming and land use change elsewhere, boosting the sector’s overall greenhouse gas emissions (carbon leakage). These trade-offs mean that the implementation of new rules and mechanisms has to be carefully weighed since the priorities that the EU sets with the F2F strategy will settle the greenhouse gas sources and sinks in the bloc’s food system for the next decade at least.

Info-Box: Greenhouse gas emissions from farming and food in Europe

Greenhouse gas emissions in the agriculture sector consist mainly of methane (enteric fermentation in ruminant animals, treatment of manure), and nitrous oxide (N2O – from spreading mineral and organic fertilisers, manure management).

Around 10 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the European Union come from the agriculture sector (without emissions from land use and land use change and forestry [LULUCF]). Nearly 70 percent of the EU’s farming sector emissions come from the animal sector. 68 percent of total agricultural land in the EU is used for animal production.

Between 1990 and 2015, emissions from the sector declined by 20 percent, making it the only major farm sector in the world to have reduced its greenhouse gas emissions. These reductions affected both methane emissions from livestock, as well as N2O emissions from agricultural soils and are attributed to the Nitrates Directive and a reduction in cattle numbers. However, recent years have seen an increase in nitrous oxide emissions at EU level, mostly due to the intensified use of inorganic fertilisers on cropland and grassland. Agriculture emissions are not projected to fall in the next decade, as EU member states are planning rather low emission reductions in this sector, the European Environment Agency has said.

Ascertaining greenhouse gas emissions from “food” is particularly difficult and it includes many emissions recorded under different categories during its journey from “farm to fork”, i.e. manufacturing, processing, packaging, transportation, consumption, discarding. A different and not harmonised accounting approach (consumption based) is used to calculate the carbon footprint of peoples’ diets. Researchers have estimated that greenhouse gas emissions from food consumption in the EU range from 610 to 1460 CO2-eq per person per year and that the consumption of animal products has the largest effect on the greenhouse gas intensity of diets. “If European diets were in line with dietary recommendations, the environmental footprint of food systems would be significantly reduced,” the F2F strategy states.

.](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/farming-emissions-pic.jpg?itok=0KKI2oj9)

The EU is still in the process of finding the best scalable methods to achieve greenhouse gas reduction in agriculture. The Commission will draw on the experience of pilot projects to identify the farming methods that can reliably increase the organic matter in soil and thereby its carbon uptake. Once the questions about measurement, monitoring, verification, additionality and costs of sequestering carbon in soils have been resolved, farmers could get an additional income from participating in carbon markets.

The F2F’s two main climate-related targets have the following emission implications:

- Five percent reduction in nutrient losses and an ensuing 20 percent reduction in fertiliser use. The use of nitrogen fertilisers causes the release of nitrous oxide (N₂O - laughing gas), a very potent greenhouse gas. Global N2O emissions have been growing unabated for decades, albeit not in the EU and the U.S., where regulations designed to reduce nitrogen accumulation in soils and waterways have prevented this.

- Increasing the share of agricultural land under organic farming to at least 25 percent. Producing food without the use of pesticides and chemical fertilisers reduces N2O emissions and healthy soils under organic farming can become a carbon sink by improving carbon sequestration. However, others argue that a reduction in yields under organic farming would lead to clearing more land for farming abroad, causing a rise in emissions overall.

As the F2F strategy remains to be filled in with actual legislation and initiatives and important keywords such as “sustainable” food system still need to be defined, the specific greenhouse gas reduction potential of its measures is unknown.

The Farm to Fork strategy and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) represents the single largest slice of the European Union’s budget. The multi-annual budget for the next funding period (2021-2027) will amount to 387 billion euros, around 26 percent of the EU’s total budget. Farmers in the EU receive a large part of their income from the CAP funds. The bulk of the money (under the so-called first pillar of the CAP) is paid out as direct payments to farmers according to the size of their operation (calculated on a hectare basis). These payments are administered and controlled by the member states, as are the decisions on how funds from the CAP’s second pillar for “rural development” are used.

Spending under the CAP is expected to make up between 40 and 45 percent of the overall EU budget contribution to the Green Deal. Forty percent of the CAP budget will be “climate-relevant,” the European Commission has said.

In the past, the CAP has been heavily criticised for not contributing to climate action in farming. NGOs have long demanded that the CAP subsidies (making up around 26 percent of the total EU budget) must be tied to mandatory best practice rules that improve biodiversity and environmental conditions, and reduce greenhouse gases. They hoped that the objectives of the Farm to Fork strategy would be used to reform the CAP. However, when the European Green Deal and the F2F strategy were published, the proposal for the CAP for the next funding period (2021-2027) had already been completed and the European Commission resolved to stick with its policies rather than starting anew. As a result, many observers have lamented the insufficient inclusion of F2F premises in the CAP. Other parts of the EU legislative branch, namely the majority in the European Parliament and the Agriculture Council of member states’ ministers, have chosen to keep the F2F strategy largely separate from the CAP negotiations; the European Commission has published a factsheet detailing where the European Parliament and Council positions are at odds with the objectives of the Green Deal. Delays in the legislative process have resulted in an extension of the rules under the last funding period until the end of 2022, when the new rules are coming into force. Trilogue negotiations between the European Parliament, Council and Commission are expected to be completed by summer 2021.

Changes have been introduced to the next CAP, which could also help deliver the objectives of the Green Deal and the F2F. These are:

- An increase (compared to the first draft) in funding for rural development, the second pillar of the CAP, e.g. enhancing ecosystems, promoting resource efficiency

- Eco-schemes – a minimum of 20 percent of the money in the first pillar (usually used for direct payments based on hectares) will go to farmers who perform additional activities that are related to climate, environment, animal welfare and antimicrobial resistance and contribute to reaching the targets of the EU Green Deal. Offering eco-schemes is mandatory for member states, participating in them is voluntary for farmers

- (Enhanced) Conditionality under the first pillar. To receive income support, farmers must adhere to basic requirements called Good Agricultural and Ecological Conditions (GAEC). Influenced by the F2F and the Green Deal, they should be linked to environment and climate-friendly farming practices and standards, but have been criticised as being too lenient to make a difference

- CAP strategic plans. To receive funding in the next budget period, member states will have to submit so-called CAP strategic plans that detail how they are planning to implement the CAP rules. On these plans, the Commission gives recommendations to ensure “compliance with Green Deal ambitions and […] six Farm to Fork and biodiversity strategy targets. After a review process, it approves the member states’ plans.

Farm to Fork and CAP in Germany

German environmental NGOs generally welcomed the Farm to Fork strategy as an important building block for a sustainable food system. The Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU) said the “great weakness” of the F2F and biodiversity strategies was that they wouldn’t change other important EU policies. NGO Germanwatch criticised that the F2F strategy didn’t include a climate target for agriculture and the food system. Although the strategy pointed out that 70 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the sector come from livestock farming, “no climate target is imposed on industrial animal husbandry,” Germanwatch said.

The German Farmers’ Association (DBV), on the other hand, called the F2F and biodiversity strategies a “general attack on the whole of European agriculture.” General politically driven reduction targets for pesticides and other tools are “counterproductive,” DBV President Joachim Rukwied said. He warned that if farmers were left alone with the costs of more environmental and climate action, food production would increasingly move to third countries and large numbers of farms would be abandoned in Europe.

During European Council negotiations in autumn 2020, other politicians didn’t perceive Germany’s agriculture ministry (BMEL) as a particularly progressive force on implementing Farm to Fork objectives into the CAP. When the strategy was first published, minister Julia Klöckner warned that “our farmers can only achieve ambitious goals if they are also backed financially. And that is why I would have liked to see an equally clear commitment to a well-funded agricultural budget today.”

In the beginning of March 2021, the ministry published its first key points for the CAP strategic plan that will have to be passed by the German Parliament before it is submitted to the European Commission before 1 January 2022. The agriculture ministry suggests ringfencing 20 percent of pillar 1 payments for eco-schemes (900 million euros per year). It has chosen to offer the following six eco-schemes:

- Increase the size of non-productive areas and landscape elements on which neither arable farming nor animal husbandry is practised beyond the three percent prescribed in the conditionality

- Enhance these non-productive areas by planting flowering strips, flowering islands or old grass strips to increase biodiversity

- Cultivate diverse crops in arable farming, including legumes - indigenous protein crops that can be used as a source of protein for animal feed

- Extensify permanent grassland (decrease the use of capital and inputs relative to land area). For example, grassland is mown or fertilised less frequently and used by fewer animals

- Introduce grazing premiums for sheep, goats or suckler cows to preserve ecologically valuable areas and increase animal welfare

- Maintain agroforestry systems on arable land or permanent grassland. This involves farming with the inclusion of trees and shrubs.

Eight percent of funds from the first pillar will be shifted to the second pillar of the CAP (previously 6%), where the money (400 million euros per year total) will be used by the German states for the “promotion of climate and environmental protection measures, strengthening competitiveness and rural areas.”

Enhanced conditionality in the German CAP plan includes that “at least three percent of arable land must be set aside by farmers as non-productive land or landscape elements” and no conversion of permanent grasslands may occur in peatlands and wetlands.

Farmers’ association AbL said the ministry had failed to adequately harness the opportunity of eco-schemes – using 20 percent of pillar 1 funds towards them was not sufficient to meet the ecological and economical challenges of farmers. An annually increasing level of these funds, starting at 30 percent, would be needed. They also said that important eco-schemes, such as rewarding reduced pesticide and mineral fertiliser use and small-scale farming, had not been included. Farmer association DBV welcomed the eco-schemes as proposed by the ministry but criticised the increased shifting of funds from the first to the second pillar of the CAP as something that would “weaken” farming operations and cause more red tape.

What are the implications of F2F for the EU’s food production?

One of the main points of contention with the F2F strategy has been the projected impact of its fertiliser and pesticide reduction targets and the increase in organically farmed area on overall food production in Europe. With the COVID-19 pandemic, food security has come into focus even more and critics of the F2F strategy have said that in order to provide enough locally grown food to Europeans, changes to the strategy would be necessary. The EU environment commissioner, on the other hand, argued that since ”food security is no longer an issue in the EU,” sustainability, climate and biodiversity should be moved to the heart of the bloc’s food and farming policies.

With no impact assessment of the strategy provided by the European Commission, others have attempted to quantify the effects of the F2F targets. An impact report published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has projected that the total value of EU agricultural output would shrink by 12 percent, domestic prices would rise by 17 percent and global commodity prices by nine percent, EU exports would drop by 20 percent and the number of people suffering from food insecurity globally would rise by 22 million. However, another researcher found that these highly pessimistic projections were largely due to very rough or incomplete assumptions on the European farming system, land prices and productivity under less fertiliser use, while confirming that the F2F targets would indeed “significantly reduce output,” which in turn could lead to more land use and deforestation abroad. While acknowledging the likely decrease in productivity in the short to medium term, EU officials and others have pointed out that part of the strategy is about saving food (less food waste, change in diets) and making sustainably produced food the most affordable, which have to be included in the equation to ascertain the F2F strategy’s impact on food security.

The F2F strategy and global trade

Upon presenting the F2F strategy, the European Commission has shown itself very aware that Europe could not pursue the goal of a sustainable and climate-friendly food system alone. There was little point in Europe becoming an “oasis of sustainability,” an EU official said in autumn 2020. Since environment, climate and biodiversity are all transboundary, global issues, the EU would endeavour to work with its international partners to find a consensus on what kind of sustainable food system should be built.

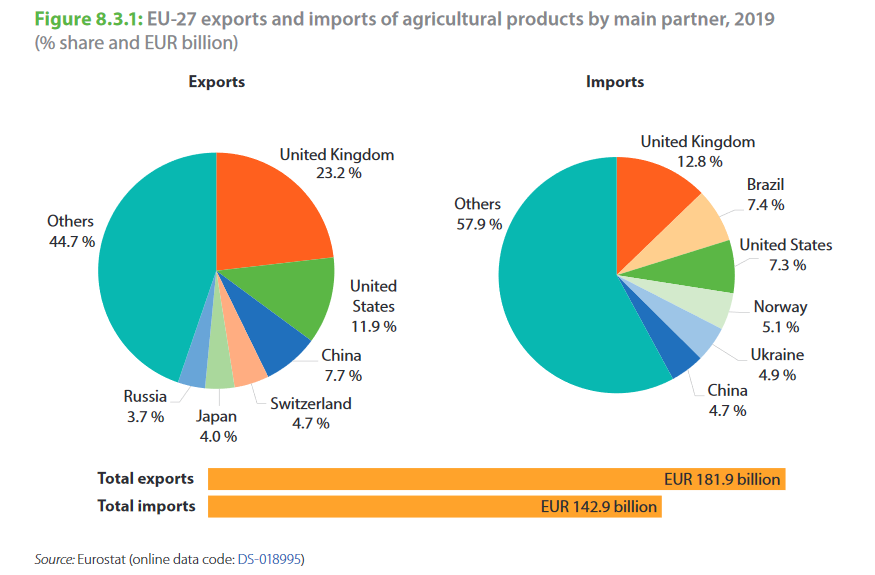

Info-Box: EU agrifood trade at a glance

As the biggest global food importer and exporter, the EU food and drink industry also affects the environmental and social footprint of global trade.

Trade in agricultural goods accounted for 8% of total EU international trade in goods in 2019 and at 325 billion euros it was slightly more than double what it was in 2006. The EU had a trade surplus of 39 billion euros in the trade of agricultural goods, the value of exports (EUR 181.9 billion) exceeding that of imports (EUR 142.9 billion). Whilst the EU imported mainly raw, unprocessed agricultural goods, it principally exported processed food products.

Trade in agricultural products can be subdivided into three main groups: animals and animal products, crop products and foodstuffs. In 2019, the EU’s trade was split as follows:

Animals: 23% in exports | 22% in imports

Crops: 23% in exports | 45% in imports

Foodstuffs: 54% in exports | 34% in imports

In the period between 2002 and 2019, the EU’s trade surplus in foodstuffs grew relatively steadily, the deficit for crops widened. There was a trade surplus of 10.8 billion euros in animals and animal products in 2019, representing a turnaround from the more balanced trade position in the period between 2002 and 2009.

The United Kingdom was the main recipient of EU exports (23.2%) of agricultural products in 2019 and was the main origin of EU imports (12.8%). The value of agricultural goods imported by the EU from Brazil (EUR 10.6 billion) was higher than imports from all other countries with the exception of the United Kingdom. About half (48.1 %) of these imports concerned crop products. Oilcakes and soyabeans (commonly used as animal feed) made up 39% of agrifood imports from Brazil in 2019. Imports represent about half of the oilseed used in animal feed annually.

Under the subheadline “Promoting the global transition,” the F2F strategy includes the following premises for handling trade agreements and positions in international fora:

- Pursue the development of green alliances on sustainable food systems with all its partners in bilateral, regional and multilateral fora

- Promote the global transition to sustainable food systems in international standard-setting bodies (e.g. Codex) and international events (e.g. UN Summit on Food Systems in 2021)

- Lead the work on international sustainability standards and environmental footprint calculation methods in multilateral fora to promote the uptake of sustainability standards

- Include an ambitious sustainability chapter, among others on food, in all the EU’s bilateral trade agreements

- Promote appropriate labelling schemes to ensure that food imported into the EU is gradually produced in a sustainable way

- Take into account environmental aspects when assessing requests for import tolerances for pesticide substances no longer approved in the EU

More than 30 percent of the land required to meet EU food demand is located outside Europe, the European Parliament has stated. The bloc is a major importer of animal feed, e.g. soya from South American countries. Setting new standards regarding the sustainable production of these goods can have considerable impact on Europe’s trading partners. In establishing the “legislative framework for sustainable food systems,” including new standards and labelling obligations, all products placed on the EU market will have to comply with stricter rules. For example, the Commission will present a legislative proposal to limit the placing on the market of products associated with deforestation in the first half of 2021.

EU officials have stressed that in all these changes they will respect the proportionality and non-discrimination rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

If legislation following the F2F strategy obliges EU farmers to improve their environmental standards, increase their production costs or reduce their productivity, their products will struggle to compete with imported goods. This could be prevented by setting standards for the production practices of foreign goods (e.g. carbon footprints), which would function as a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM). The German agriculture ministry has signalled support for this idea.

Trading partner reactions to Farm to Fork

The current lack of an impact assessment on Farm to Fork has left many observers from non-EU countries at a loss as to what the new strategy would mean for their trade relations with the EU. This was reflected in the questions raised by 50 members of embassies and missions of third countries during an informative session the Commission hosted on the F2F strategy in September 2020.

The United States’ secretary of agriculture (Trump administration) called the strategy “protectionist” and said it was “extremely problematic” if the EU tried to impose its new food system standards on international trade.

Developing countries that struggle to comply with the new EU standards could turn to other customers in regions with less stringent policies – something that overall would not benefit sustainability and climate mitigation in the food system, others have warned.