French and German energy discrepancies hamper joint EU climate strategy

*** Please note: this article is part of a CLEW cross-border cooperation, exploring the Franco-German approaches to climate and energy and how these affect the vision of the EU’s energy future. You can find the full dossier here.***

Before a wave of riots across France in early July 2023 threw Emmanuel Macron’s agenda in disarray, it looked like the first official state visit of a French president to Germany in almost 25 years was going to be beset with a list of unsorted energy and climate challenges. Germany's presidential office assured that the postponed state visit will be held "as soon as possible" – the list of energy challenges is unlikely to become any shorter in the interim.

Sixty years after signing their historic Elysée Treaty, which formally ended decades of rivalry and opened an unparalleled political partnership between the neighbours, France and Germany find themselves at the forefront of a dual crisis that affects these core tenets of the EU: safeguarding energy supply after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine while also getting ahead with the unremittingly urgent task of decarbonising its economy - which is supposed to have reached net-zero by 2050, about the time the next full-blown state visit is due at the current rhythm. However, some of the ongoing bilateral energy disputes cast a shadow that reaches back all the way to the European Union’s origins as a project based on a common line on energy policy and industrial stability after the Second World War.

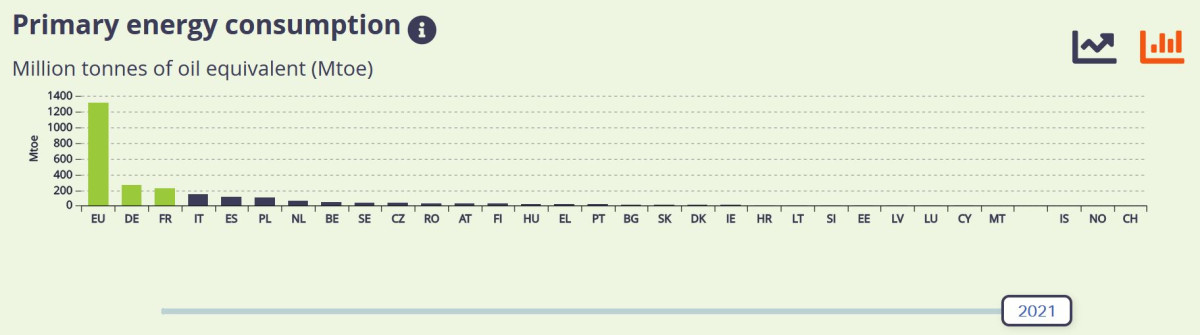

Macron has been visiting Germany on numerous working visits during his tenure and meets with German chancellor Olaf Scholz regularly to talk politics between the bloc’s two most populous countries, who together account for roughly 45 percent of its GDP and nearly 40 percent of energy consumption. The state visit one year ahead of the 2024 European elections was meant to send a message that the ‘Franco-German engine’ for finding compromises on European integration is still intact - after a calamitous year dominated by Russia's war but also by glaring gaps in the two core member states’ energy strategies. The visit thus should have been a nod to the challenges ahead, which both governments agreed to approach by “looking out at the world together,” as Germany’s presidential office put it.

Meanwhile, a lack of common vision between Paris and Berlin in the preceding months has come with serious implications for the EU’s climate ambitions. At the height of Europe’s energy crisis, the engine showed clear signs of malfunction, as Paris and Berlin allowed themselves to engage in noisy quarrels over the use for nuclear power, the role of gas in the energy transition and the future of combustion engines. All these differences point at crucial decisions the EU must take together with respect to the funding of its energy plans, aspects of supply security, as well as wider trade and industrial policy frameworks. The dispute exposed deeper risks in the bloc’s coherence regarding climate neutrality, said Sven Rösner, head of the Franco-German Office for the Energy Transition. “There’s a risk that the gulf on these matters weakens the pair’s ability to act as a progressive force in European climate action that it has been in the past,” the head of the bilateral government platform for energy policy coordination argued.

National energy perspectives no longer offer viable solutions

Encouragingly, the crisis also showed that European solidarity worked in practice: French help was instrumental in getting Germany out of its self-dug Russian gas trap. Electricity imports from German coal plants and renewables helped to keep the lights on in France when half of its nuclear reactor fleet was taken offline for maintenance or a lack of cooling water due to dry and hot weather that also cut hydropower output. “Unfortunately, this encouraging sign has been buried by disagreements,” often centered around national energy ‘sovereignty,’ Rösner said. While energy policy is seen as a shared competence within the EU in order to establish a functioning common market and supply security, decision-making ultimately rests within the discretion of national governments.* Asked about the effects of the spat on climate policy progress during the crisis, the EU Commission made clear it will not “comment on the bilateral relationship between two of our member states.” But applying national perspectives no longer offers a viable solution, French-German policy mediator Rösner said. “Sovereignty today is only achievable at the European level – and there will be no sovereignty without solidarity.”

A spokesperson for Germany’s economy and climate action ministry (BMWK) said differences on energy that have an effect also at the European level are “nothing new and perfectly normal.” However, she agreed it is regrettable that “certain controversial topics” that dominate the public debate cause that many of the joint French-German initiatives “at times receive too little appreciation.” In the context of the G7 or the UN climate conferences, both countries had shown unity on various positions and pulled together on relevant aspects of the EU’s “Fit-for-55” climate package. “In the end, we always manage to find good and acceptable compromises, especially on topics where both have different initial positions,” the spokesperson said, adding that the current government had even intensified bilateral efforts.

This conclusion does not seem to resonate with many French and German citizens so far: in a bi-national survey by the German Heinrich-Böll-Foundation and the French Ecologic Policy Foundation released in early 2023, about 40 percent in each country said relations had deteriorated in the crisis, while only 17 percent in France and 12 percent in Germany regarded them as improved. More than 80 percent of respondents in both countries said a functioning Franco-German engine remains essential. Cooperation on energy was overwhelmingly considered the most important job for the two governments, followed by security policy, trade and climate action. Yet, as of mid-2023, energy cooperation appears to be far from these popular wishes, as France took the lead in a ‘nuclear alliance’ of countries aiming to ingrain non-renewable nuclear energy in the bloc’s renewable energy plans, an outcome Germany vehemently opposed. A deal on intermediate renewable power goals that included nuclear power provisions allowed EU states to move forward, but the problems it left became obvious when Paris was temporarily shunned by a ‘Friends of Renewables’ group meeting ahead of the EU energy council where it was agreed.

While France eventually did join the pro-renewable energy meeting, “the way it projected its interest in EU policies was emblematic of a certain bluntness it shared with Berlin throughout the energy crisis that did little to solidify European cohesion,” said Kenny Kremer, who oversees Franco-German relations at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP). “Last-minute interventions based on national interests have been perceived as egoistical and self-centered by many other EU states,” Kremer said. As France snubbed others with its insistence on nuclear energy, Germany’s national solo effort became visible in its scarcely coordinated 200 billion-euro energy crisis response. More broadly, Germany’s position on energy often came across as particularly selfish, with Berlin “claiming the moral high ground on environmental policies while burning a lot of coal and refusing to let go of combustion engines,” Kremer said.

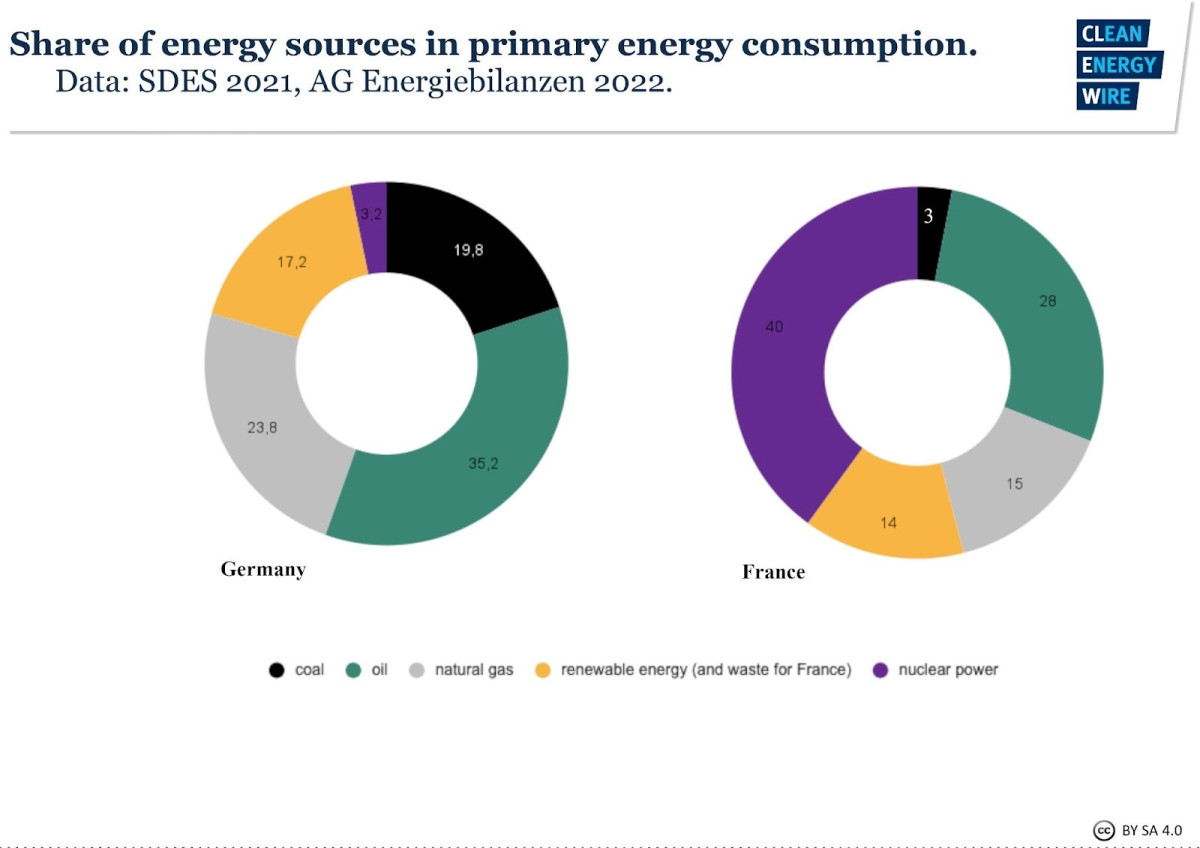

Finger-pointing misses the point: agreeing on Europe’s future energy system

The fact that France had a higher share of renewables in its energy consumption than Germany in 2022 fits this narrative. However, a closer inspection reveals that wind and solar power, widely agreed to be the workhorses for decarbonising the global power supply, have been deployed much faster in Germany than in France, whose renewable energy credentials rests on a sizeable capacity of bioenergy and hydropower that cannot be expanded further easily. While France incidentally boasts the largest land area and abundant production potential for solar and wind power, it was the only country in the EU to miss its 2020 renewable energy target.

But pointing fingers and measuring annual expansion levels or current shares in the energy mix misses the point of coming to a deeper agreement on the path France and Germany want to see Europe take towards its goal of achieving climate neutrality and greater energy sovereignty, as both Macron and Scholz repeatedly vowed. The common objectives outlined in the European Green Deal compel all member states to improve coordination – and France and Germany are positioned to spearhead this effort by seemingly irreconcilable approaches which need to be brought into alignment.

Europe needs to expand and diversify its energy infrastructure, said Joachim Hein of the Federation of German Industries (BDI). “This cannot be done if member states are in conflict, especially neighbouring ones,” Hein said. If Europe is to stand its ground vis-à-vis other world regions. The EU gauges the total costs for meeting the 2030 climate targets at about 470 billion euros annually. Attracting private investments in the relevant sectors is seen as a prerequisite, which a more coherent regulatory approach is likely to facilitate. “The internal electricity market is Europe’s central energy policy project,” Hein added, for which clarity on investments is crucial. Jean-Baptiste Léger from French industry federation Medef agrees that differences on the power market's structure must not hinder a joint industry push. "The vision is that of an energy that must enable the competitiveness of industrial sectors and companies in Europe, and everyone agrees on this." Léger said it was necessary to focus on what better coordination can do for France and Europe, defending the principle of technological neutrality to reduce emissions and create new jobs along the way. "The challenge now is to

roll up our sleeves, to build the infrastructures for the energy transition, to make the business models of this new sector valid, and to move forward with as much pragmatism as possible."

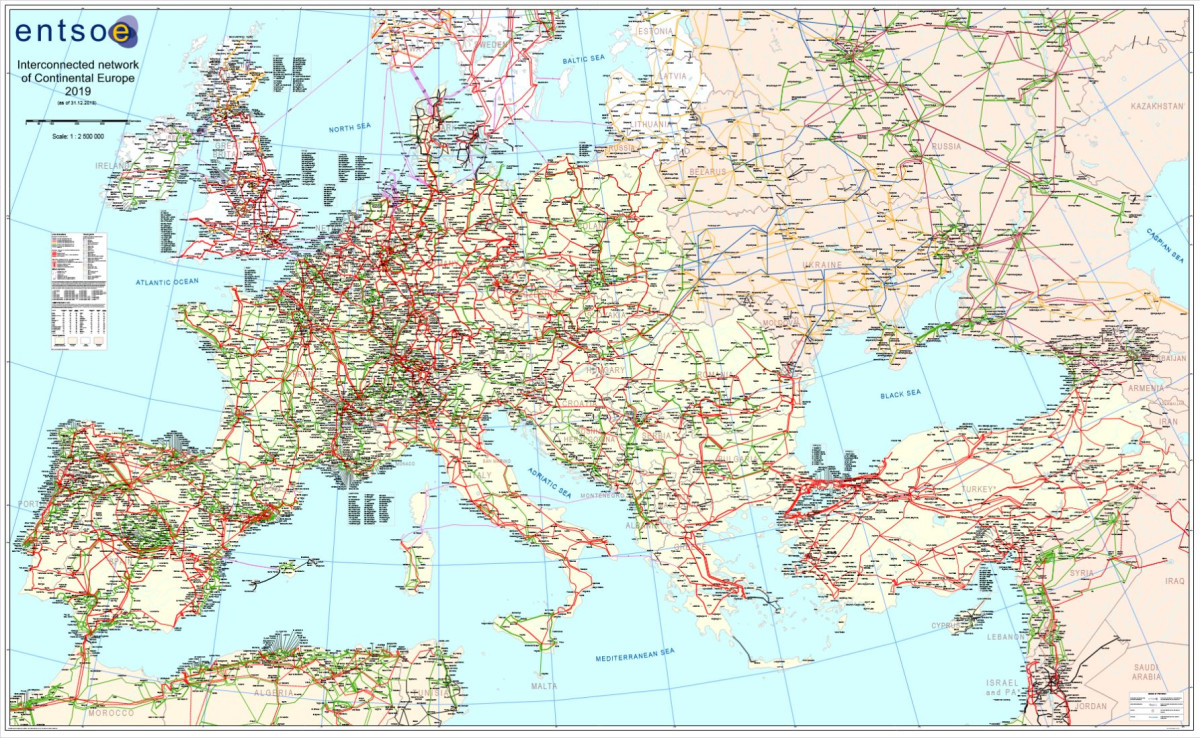

Pragmatism has also been needed during the energy crisis, whose largely successful mitigation by France and Germany showed that big levers can be pulled fast if governments collaborate. However, pragmatism on a longer term so far has often been practiced from a national perspective and widened a gap that the geopolitical tensions of 2022 revealed. EU policy think tank Jacques Delors Centre Berlin in early 2023 remarked the need to step up coordination across the board is needed to make key climate projects a success: managing the REPowerEU crisis response, reforming the EU power market or pushing interconnections as key steps for the Green Deal to succeed – in addition to jointly avoiding excess fossil infrastructure investments that will lead to stranded investments rather than lower emissions.

EU-wide growth of renewables commands growing interconnection

Crucially, the think tank also cited the need for greater joint efforts to make Europe a production location for clean technology – a task that German economy minister Robert Habeck and his French colleague Bruno LeMaire addressed in a Franco-German response to the industrial policy challenge posed by the green subsidy programme Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the U.S. which was widely hailed as successful. The coordinated reaction to the IRA was preceded by a joint declaration where both ministers acknowledged their countries “have a key role to play in this unprecedented context” to break up Europe’s spiral of high energy prices, rising inflation and falling competitiveness. The declaration marked “the first step of a new Franco-German commitment line,” they promised. However, it was only achieved after a vexed debate about a new hydrogen-ready gas pipeline connection from Spain to northern Europe, which France deemed unnecessary because it plans to use its own LNG import infrastructure and wants to produce hydrogen with nuclear power – meaning it would rely on so-called ‘pink hydrogen’, rather than the green hydrogen standard Germany is vehemently calling for. While climate neutrality gives the Franco-German engine a destination for where to take the EU, it appears there are two steering wheels involved that complicate this task.

National reservations dominate the headlines about Franco-German energy relations despite the fact that there is wide agreement on the vast majority of tasks ahead, despite the fact that the concept of national electricity systems is gradually fading in Europe as more and more electrons cross borders. Since the liberalisation of power markets in the 1990s, interconnections between national energy markets have greatly intensified across Europe, putting Germany and France at the center of the world’s largest integrated electricity system; the Continental European Synchronous Area (CESA); where the pair boasts the largest generation capacities.

“We need each other,” said Ines Bouacida, energy researcher at the French think tank Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI). “To balance the networks, to ensure security of supply, we are interconnected with our neighbours,” she explained. The fast-growing share of renewable energy sources projected by the EU will only increase this mutual reliance, driven by shifting weather conditions in Europe that have let the national power generation fluctuate. It also generally guarantees that high outputs are generated somewhere in the region. “Interconnections ensure that everyone gets the electricity they need,” she stressed, even though the current level of integration is far from optimising fast intercontinental transfers or avoid curtailment because local grids have nowhere to redirect excess power.

Improving the joint exploitation of electricity sources across Europe would unequivocally benefit France, Macron acknowledged in late 2022. Increasing the number of interconnectors would also lead to a more equal and lower price level for power between both states, Germany’s economy ministry underlined following winter 2022/2023. The more connections available, the better supply and demand can be balanced across the border and bridge relative generation costs — including those for fossil-based power generation and CO2 emissions allowances. Conversely, underdeveloped coordination means EU countries compete for foreign supplies, rather than maximising domestic ones.

Today’s conundrum steeped in energy crisis response of the 1970s

Upholding the conundrum exposed by the current energy crisis would not be the first time that a shock to energy architecture has lead France and Germany to stray from their shared vision of cooperation over national supremacy. Today’s differences in energy architecture on both sides of the Rhine River border are steeped in diverging responses to another energy crisis: the oil price shock of the 1970s. Initially nuclear energy had been a core tenet of European integration and both countries had equally banked on the technology in the post-war ‘economic miracle’ decades. However, faced with the oil crisis, Germany embraced its domestic coal riches and relied on its bigger spending power to outbid other European buyers on oil markets, meaning it relied on a combination of its own natural resources and open markets to secure supply. This was much to the annoyance of France, which lacked a substantial coal industry and in vain had pleaded for joint oil price controls from European buyers. As a result, Paris went out on a reactor-building spree, the Messmer Plan, which saw the fleet increase considerably throughout the 1980s.

With its national nuclear arms programme already fully developed during this time, France sought to extend use from the military to the civilian realm. At the same time in Germany, which lacked nuclear arms, anti-nuclear protests (that also helped birth the country’s Green Party) pushed society further away from the technology – and a few industrious citizen cooperatives embarked on first renewable power projects. “The Germans tend to believe that there is no separation between the civilian and military sectors, and this is what scares them,” said energy historian Alain Beltran from the Sorbonne University in Paris. “By contrast, in France, there is no immediate link between civil and military realm. This is a fundamental difference.”

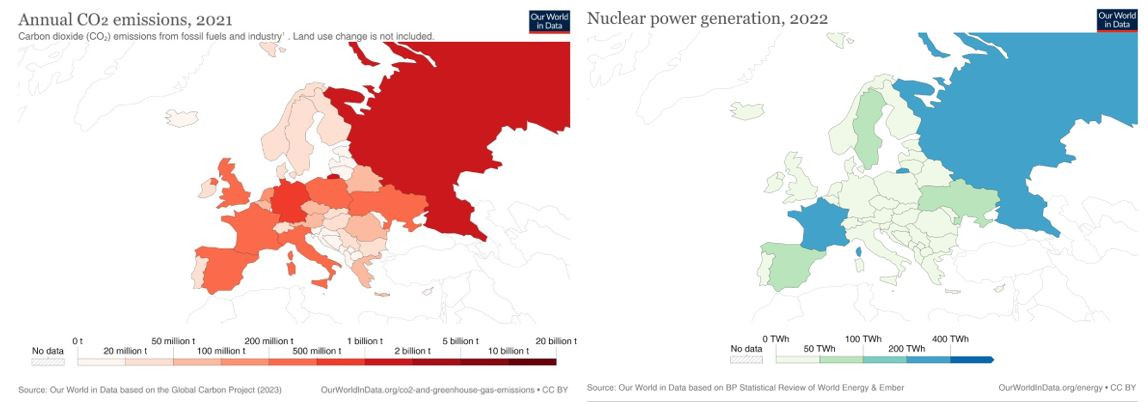

Unfettered by the Chernobyl disaster, nuclear power firmly established itself as a mainstay of the French electricity system – which fit its desire for relative control over supply and chimed increased concerns about fossil fuel emissions in the 1990s. "France has had an energy policy based on greater independence, with an electro-nuclear policy as a major axis,” Beltran said. Germany, on the other hand, went on to push for a full exit from nuclear power and started to phase-in renewable energy in earnest, while at the same time betting on concepts like ‘clean coal’ plants or gas as a ‘bridge technology’ towards decarbonisation which it could freely buy on the market – or through preferential agreements as with Russia, which German reunification helped greatly reinforce.

France and Germany share most energy challenges despite decades of diverging strategies

Fast-forward to 2022, excluding greater sovereignty from its energy strategy turned out to be a major miscalculation by Germany. Scholz’s ‘Zeitenwende’ policy – which included the 200-billion euro shield – in response to Russia’s war kicked off a turbulent period in which the country paid dearly for its previous reliance on cheap Russian gas. Simultaneously, it saw years of warnings from its EU partners, particularly in the east, over the hapless Nord Stream 2 pipeline come true in what had been widely seen as a massive geopolitical own-goal. Despite its nuclear backbone and accent on sovereignty lowering exposure to Russia, France too faced massive repercussions in the crisis. France spent 45 billion euros on support programmes and ended up fully nationalising its key energy company and reactor operator, EDF, for nearly 10 billion euros. And while nuclear dominates the national electricity mix, only about a quarter of the total energy consumption in both countries is covered electrically. France imports most of its energy in the form of fossil fuels to run cars, fire up industry sites or heat homes – and in 2022 even became the world’s largest importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the U.S., some of which subsequently was sent on to Germany.

Faced with strikingly similar challenges despite decades of difference – and far-right parties in both countries starting to capitalise on fears of high energy prices and difficult emissions reduction policies – solutions from either side of the Rhine river have so far failed to provide a convincing picture of Europe’s energy and climate strategy moving forward. In both cases, the dominant sources of energy created economic and social linkages that are difficult to disentangle, which Germany has found in its heated but ultimately successful negotiations for a coal phase-out in 2038 - a date that economic realities might ultimately ring in faster. France’s ‘nuclear renaissance’ and German plans to increase its capacity for gas-fired power production (built with the later use of green hydrogen in mind, although this aim is still beset with unresolved technical and logistical difficulties) both remain concepts anchored in national path dependencies.

“The debate on the way electricity is produced in our country is taking over the public space as soon as we talk about energy,” said Phuc-Vinh Nguyen, energy researcher at the Paris-based branch of think tank Jacques Delors Institute. “This leads to a focus that is on either renewable energy or nuclear power, and not really on how we want to move away from fossil fuels,” he adds, advocating for more speed and cooperation in areas beyond electricity. This is particularly true for transport, which is the biggest emitter in France, but in Germany has not reduced its carbon footprint in a meaningful way since 1990. “We will need proactive policies in the very short term.”

Multitude of existing Franco-German initiatives needs solid strategic footing

In acknowledgement of the need to break free from trodden paths, French president Macron reached out at Germany on multiple occasions since taking over office in 2017, appealing to a “Franco-German momentum” that should put Europe ahead in the global race for clean technologies in transport, housing, industry or agriculture. But the proposals, including an EU carbon border tax (CBAM) and an internal carbon price and targeted efforts to ramp up harmonised infrastructure, did not bear fruit under Scholz’ predecessor, Angela Merkel. This was not least due to the German industry’s reservations about effects on competitiveness, which persisted even when key parts of the proposals were adopted some six years later.

Yet, also the French appetite for a “momentum” at times appears to have ebbed in the interim. Its approach to secure EU funding for reactor construction by all means nagged on the ability to make incremental progress on the energy policy fields with shared competences that are left for EU-wide approaches, mostly renewable power and efficiency. Despite it forging an alliance with other states interested in reviewing nuclear power options, France remains an outlier in that it operates the largest fleet by far and dominates Europe’s capacity for reactor construction. Such vested interests in one technology may well hamper a common line on expanding renewables.

Truly zooming out from the national perspective and move on to adopt a European one could change the calculus both in Paris and Berlin, said Murielle Gagnebin, France expert for the Agora Energiewende think tank in Berlin. “The cooperation between France and Germany on both energy and climate leaves a lot to be desired still,” she said, despite a multitude of already existing initiatives aimed at pushing joint activities across the Rhine. These should be upgraded to make sure that the spat triggered during the 2022 energy crisis marks the starting point of a more earnest approach to energy integration, Gagnebin said. Platform such as the Franco-German Meseberg Climate Working Group, could help to purposefully close the gap in concepts for Europe’ energy future, which grow bigger with each national advance. “It’s important to ensure that the continuity of these efforts does not depend on individual commitments or affected by short-term developments, such as changes in government.”

Irrespective of the future course of nuclear power in France and Europe, agreeing on common investment and infrastructure priorities, state support rules, and on what generally constitutes a ‘green’ economy will be the decisive field of Franco-German energy cooperation at the EU level, most observers agree. A joint initiative for sourcing of raw materials France and Germany launched together with Italy that again was lauded “the opening of a new phase” in jointly thinking energy policy pointed in the right direction – but it did not yet present a truly shared strategic framework for energy policy between the governments involved. Irrespective of the route the ‘Franco-German engine’ ultimately takes, the question of what it is powered with should no longer cause a stir once another French president takes a trip to Berlin in some 25 years.