Preview 2023: Reality check set to drive resolve in Germany’s energy transition

Find more information on next year's energy and climate agenda in our Preveiw 2023 dossier: What to watch in energy & climate in Germany, Europe and beyond

Germany's energy policy took a reality check in 2022 that has overturned decades of convictions and strategic guidelines. Russia's final renunciation of the principle of peaceful trade in the sense of European and international political stability has hit Europe's largest economy harder than many other states. The late and largely forced turn away from Russian energy sources has deprived the powerful German industry of a cornerstone of its success and has done considerable damage to the credibility of German policy among its closest allies. Even though the not-so-new German coalition government under chancellor Olaf Scholz came into office only shortly before the start of Russia's war against Ukraine and the European energy crisis it fuelled, it must now pick up the pieces of many years of strategic misplanning in energy and climate policy.

On the one hand, the existing fossil import structure – particularly for natural gas – must be put on a new footing. On the other hand, the final move away from gas, oil and coal must be pushed forward more decisively than ever. In the view of many influential players in German energy and climate policy, the coalition of Scholz's Social Democrats (SPD), the Green Party and the Free Democrats (FDP) has not done badly overall: Even if decisions such as the return of coal-fired power plants and the construction of new import infrastructure for liquefied natural gas (LNG) for short-term supply security run counter to the goal of decarbonisation, the so-called "traffic light" coalition, based on the colours of the three parties, has also arguably launched some of the most ambitious projects in terms of renewable energies, efficiency and climate-friendly business that the country has ever seen.

But after a turbulent 2022, the next year must also see a physical departure from announcements and laws into the "Zeitenwende" (turn of times) in German politics proclaimed by the chancellor. Clean energy infrastructure must be built, subsidies paid out and new investors and citizens won over to put the country on track for its ambitious energy transition goals at the end of this decade. Many observers agree that Germany cannot afford another year of changed priorities and standstill in areas such as transport policy, construction policy and especially the expansion of renewable energy sources, precisely because of the severity of the crises.

Renewables

A forceful expansion of renewable power sources and corresponding infrastructure, especially transmission grids, is the most important energy transition measure the government coalition needs to implement during its tenure. Its most ambitious piece of climate legislation so far, the “Easter Package” for renewable power that was introduced in spring 2022, will fully enter into force on 1 January 2023 – and first tangible results ought to materialise during that year. The reform package is meant to greatly accelerate the buildout of renewable power sources and other measures to reach a share of 80 percent in the power mix by 2030 by tripling expansion “onshore, offshore and on the roofs.” A key condition for achieving this ambitious goal is the newly introduced principle that renewable energies serve public safety and thus override other public interests.

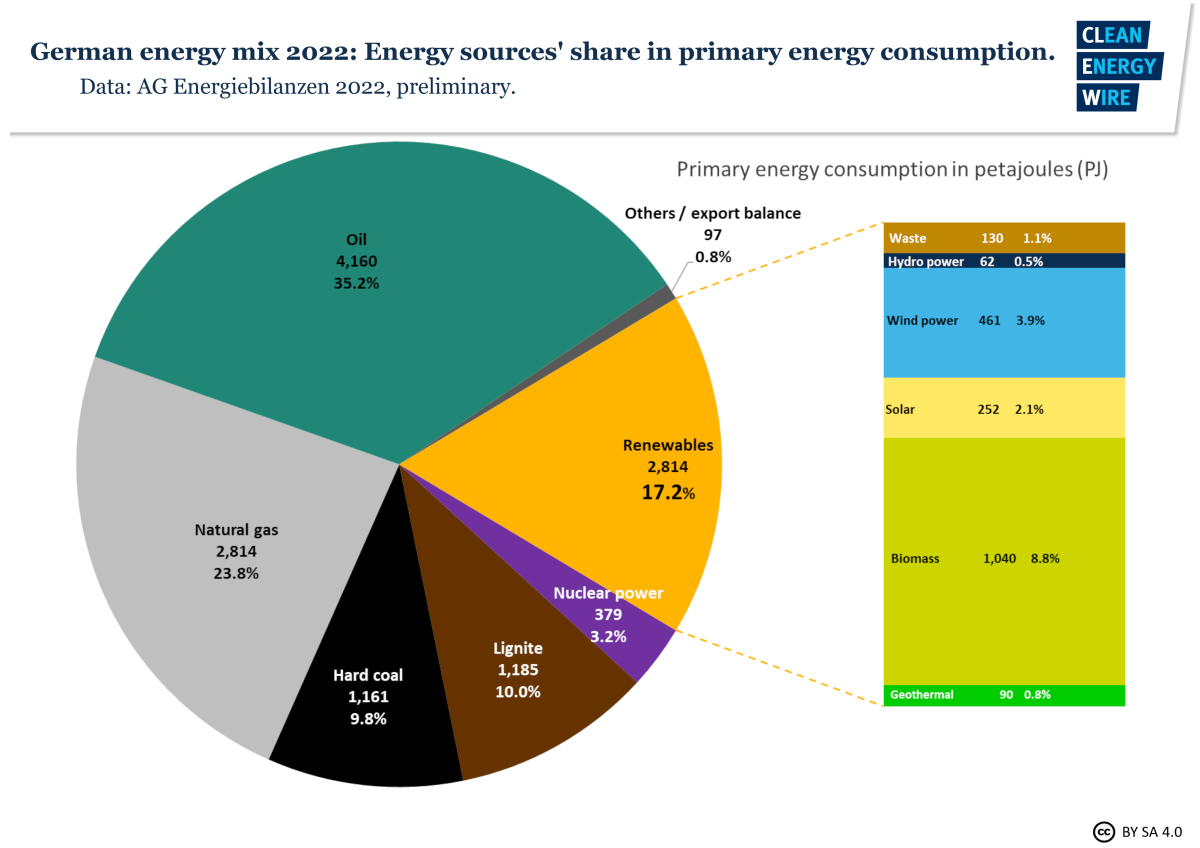

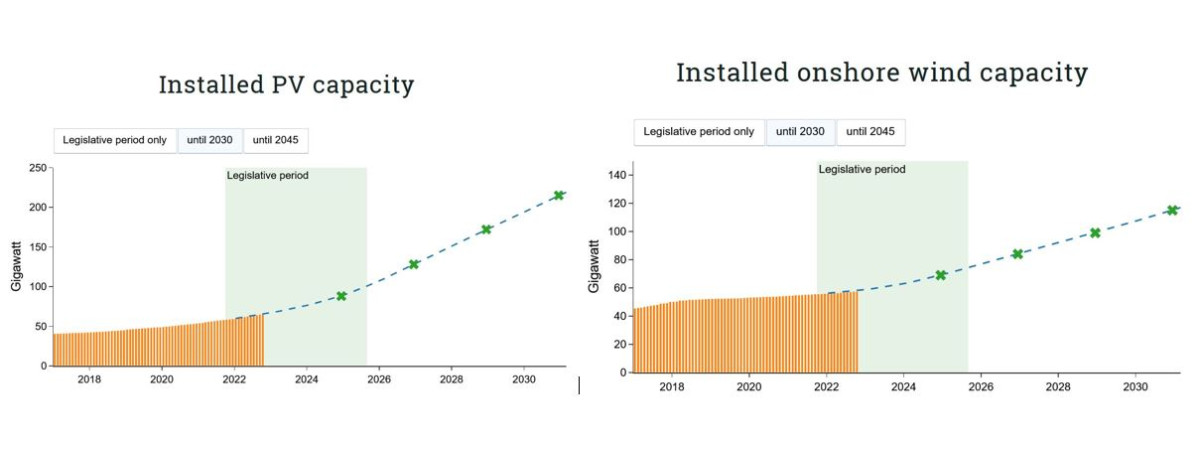

While Germany set a new renewables record share with roughly 46 percent of power consumption in 2022, capacity expansion still does not happen fast enough. The reformed renewable power law stipulates that the annual average expansion of onshore wind rises to 10 gigawatts (GW), up from just under 2 GW in 2021, and 22 GW of solar power capacity, which stood at about 5 GW in the year the government took office. The planned total 2030 capacity for onshore wind is 115 GW and 215 GW for solar PV. However, there are no clear specifications how the average expansion volumes will translate into actual construction in 2023, with annual expansion targets taking effect only in 2025.

Indicators on renewable power expansion analysed by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) suggest that a great leap forward in construction speed is needed very soon to stay on track. The pace of expansion for onshore wind power is currently less than 30 percent of what is needed and just under 40 percent for solar PV, the DIW said. For offshore wind, the current expansion speed as of late 2022 only reached 6 percent of what is necessary to meet the targeted renewables share by the end of the decade.

To make matters worse, auctions for both solar and wind power projects in Germany repeatedly were undersubscribed throughout the outgoing year. The Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) said the gap between auctioned volumes and what had ultimately been awarded to a large extent stemmed from the fact that volumes had been increased rather quickly and companies and project developers were not sufficiently prepared to ramp up their activities in parallel, while renewable power industry laments higher costs have thrown financial planning in disarray.

The average implementation time for a new onshore wind power project in the country is currently about two years. Wind power industry association BWE said several federal states take significantly longer, with some turbines taking up to six years from application to operation. “We’re far from the goal of six months promised in election campaigns,” BWE head Hermann Albers said, calling for “a true clearance kick to resolve longstanding challenges.” Albers added that the fast-tracked construction of LNG import infrastructure “shows what is possible.” Simone Peter, head of renewable power federation BEE, echoed these calls, adding that the government also needs to address a comprehensive power market reform in 2023 and take precautions for keeping green power investors in Europe that could be lured to North America by the U.S.’s Inflation Reduction Act, a subsidy program for clean power projects.

Measures that will take effect in 2023 for renewable power include:

- Introduction of higher capacities and support rates for wind and solar farms taking part in auctions in 2023

- Increase of designated land area for more renewable power installations, for example for solar PV on agricultural land and for turbines in less windy areas in southern Germany. The federal government has said the 16 states must now prepare legislation that paves the way for reserving two percent of the total land area for wind power by 2032

- Further rules to help produce more electricity from solar PV and biogas facilities, such as cutting the value-added tax for solar PV and income taxes for power sales from small arrays and increasing support rates for biomethane production

- Improving citizen participation in the energy transition by creating better partaking conditions for municipalities and making citizen energy projects exempt from partaking in auctions

- Reform of Germany’s immigration law in early 2023 is aimed at attracting people to join the labour force, as lack of skilled workers is slowing the buildout of energy transition hardware

- Already launched in December 2022 but taking effect throughout the next year is the windfall profit levy on unusually high profits of energy companies. It is intended to help fund support programmes in the energy crisis, but the renewable power industry has criticised the measure heavily, arguing it will scare away investors

In order to help power consumers overcome financial difficulties, the government brought forward the end of Germany’s renewable energy surcharge to mid-2022from 2023 as initially planned. However, despite the surcharge that enabled renewables expansion for two decades being gone, power prices are likely to stay high also in 2023, according to an analysis by consultancy Prognos. Wholesale prices in the analysed scenario will be above 500 euros per megawatt hour (MWh) – compared to roughly 200 euros/MWh in 2022 and merely 38 euros in 2019. The main driver of higher prices is an expected sustained cut of Russian gas deliveries, as gas still covered almost ten percent of public net electricity generation in the country in the outgoing year. In the rather unlikely case that Russia resumes its deliveries to reach pre-war levels, prices would still remain at about 100 euros/MWh, Prognos found.

German climate and energy policy

The government coalition intended to use 2022 to get policy and legislation on track to speed up the transition to climate neutrality. While the energy crisis took up much of the ministries’ resources, a whole raft of law reforms passed parliament this year. Keep an eye on this next year:

- The government promised to present a comprehensive climate action programme before the end of 2022 to put Germany on track to reaching its 2030 targets. It had not done so by mid-December. It already said that a second part of the full programme with all proposals would only be presented by spring 2023 (including for the transport sector, and the reform of Germany's climate law).

- The government will evaluate plans to exit coal as early as 2030 (current legislation puts the end date at 2038). Due to the “complex situation” arising from the energy crisis and efforts to temporarily put more coal plants online to push down gas use, the evaluation – which was planned for August 2022 – will be presented “at the latest in Q1 2023.”

- In March next year, preliminary data by UBA will show whether emissions in 2022 increased due to the war and its fallout.

Gas

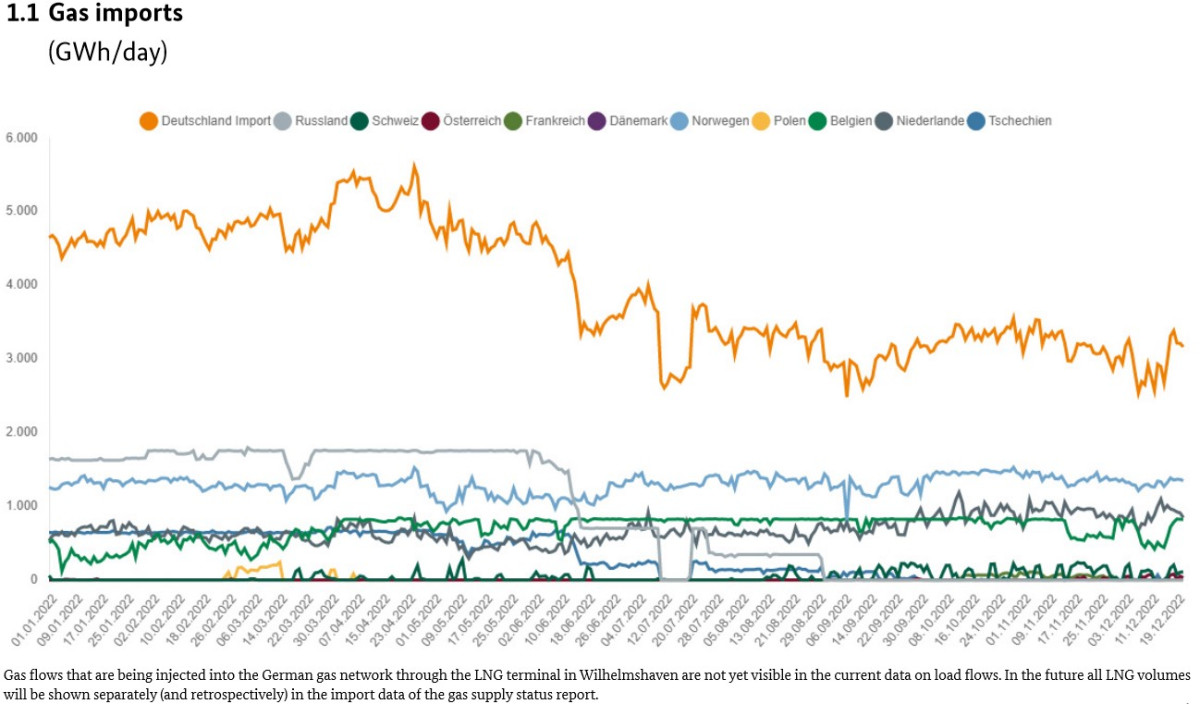

Germany’s natural gas supply was one of the unexpected top issues in 2022 – not just in gas industry circles, but at dinner tables across Europe. Whereas Russia was the country’s top supplier in 2021 (55%), Germany has ceased to receive Russian pipeline gas, leaving central Europe short in supply and the world with high prices. With full storages and mild temperatures before the start of this winter, governments and the gas industry have now shifted their focus on the winter of 2023/2024 – which could be much tougher without Russian pipeline gas to fill storages.

- 2023 may well prove to be an even sterner test for Europe, because Russian supplies could fall further, global LNG supplies will be tight – especially if Chinese demand rebounds – and the unseasonably mild temperatures seen at the start of the European winter are not guaranteed to last, wrote the International Energy Agency (IEA) in its recent report titled “How to Avoid Gas Shortages in the European Union in 2023.” The IEA said Europe will have to do much more on energy efficiency, renewables, heat pumps and simple energy saving actions.

- The weather in the first quarter of 2023 will play an enormous role in terms of how well prepared the European energy system will be as it enters the new year. Wayne Bryan, gas researcher Europe for LSEG, said the warm autumn in 2022 had perhaps “lured us into a false sense of security” by suggesting that all will be fine since storages can be filled quickly. The longer the cold months drag on – domestic consumption by households remains the main driver of gas use – serious shortages could be in store by early spring, he said at a panel meeting organised by Montel News.

- The time-honoured European policy doctrine of free markets with little government intervention has been turned upside down in 2022, ICIS analyst Andreas Schröder told Clean Energy Wire. “In 2023, nationalised utilities, state-backed investment, fixed price caps, regulated profit margins and mandated storage targets will shape European gas markets.”

- The first floating LNG terminal went online at the end of December and several more will follow throughout 2023, enabling Germany to directly import the fuel – a major step towards “guaranteeing sovereignty,” as economy minister Habeck put it. Methane leakages and local environmental risks of LNG infrastructure are currently downplayed but may soon become an issue, ICIS’s Schröder says.

- With all this infrastructure coming online – often with state support – the government will have to tell how much natural gas Germany needs in the coming years and what role this plays in the energy transition – also given its climate impact.

Coal and nuclear phase-outs

Germany's phase-out of coal and nuclear power each experienced a setback last year, as the energy crisis made additional power plant capacity necessary at short notice to secure the national electricity system as well as that of its neighbouring countries.

The completion of the nuclear phase-out, originally scheduled for the end of 2022, was postponed to April 2023 after an internal government dispute and chancellor Scholz put his foot down. The last three remaining power plants are then to be finally decommissioned and subsequently dismantled in accordance with the Chancellor's wishes. According to power plant operators, the decided phase-out can no longer be delayed another time, since important technical prerequisites, such as the procurement of new fuel rods, should have been met months ago. However, parts of the opposition, industry, but also of the governing party FDP are trying to keep a further extension of the phase-out in the debate until the very end, arguing that proceeding according to plan remains irresponsible until the energy crisis no longer poses a threat to security of supply.

As far as the coal phase-out is concerned, the situation is more complicated: with great speed, the coalition agreed on the delay of decided closures of lignite and hard coal-fired power plants in spring 2022, allowing some to return to the market and stipulating that others must remain in reserve longer than planned. While Germany's energy consumption and emissions visibly decreased in 2022 due to the energy crisis, the growing share of coal-fired power generation as a substitute for lost gas capacity runs fundamentally counter to the government's climate policy intentions. And a higher consumption of coal appears likely also in 2023, driven by the continued need to substitute gas. The government sought to limit the resurgence of coal plants by putting a deadline on the use of backup capacities, but industry representatives have signalled that a meaningful contribution to supply security by their plants must be linked to a longer-term perspective.

The crisis has also led to a split between western and eastern coal regions that is likely to stick in the new year, as the former promised to largely sticking to an earlier 2030 end date for coal and only re-firing lignite capacity in the short term, whereas the latter argue that the new situation makes an accelerated phase-out of Germany’s largest domestic fossil energy source reckless from a national perspective and directly damaging from a regional perspective.

Transport and mobility

Germany has been struggling to lower emissions in the transport sector for decades. Many experts say the government’s first 12 months in office were another lost year in the shift to green mobility, with the transport ministry led by Free Democrat (FDP) Volker Wissing widely blamed for inaction. The transition will have to gather pace rapidly to reach the sector’s climate targets: Emissions will have to fall from 148 million tonnes of CO2 in 2021 to 85 million tonnes by 2030. This will not only affect the country’s mighty car industry, but also many other policy areas, such as public transport, cycling and walking, and just transition issues.

-

The government plans to agree by spring on the policies needed to achieve climate targets in the transport sector. In a first raft of vague proposals widely derided as insufficient, the transport ministry suggested incentives for the switch to clean cars and trucks, including charging infrastructure, an extension of rail transport and support for public transport, among other steps.

-

Clean mobility experts say the country needs a coherent overall package with a fundamental reform of national taxes and levies to boost the shift to cleaner cars, complemented by a comprehensive effort to expand public transport.

-

The impact of the energy crisis on the shift to electric cars remains uncertain, as both petrol and electricity prices have risen sharply. The government wants to have 15 million electric cars on the country’s roads by 2030.

-

The increase in the share of new cars with low-emission drives has slowed in 2022 to around 12 percent. Of all new cars, almost half had an alternative drive, and 28 percent were purely battery-electric or plug-in hybrids.

-

The IAA Mobility international fair will provide an outlook on the future of emission-free transport in early September.

Industry and hydrogen

The war in Ukraine has pushed energy issues to the top of German industries’ agenda for 2023. The crisis diverted many companies’ attention away from urgent emissions reductions, but also forced them to speed up efforts to end fossil fuel dependencies. Many energy-intensive businesses will struggle to adapt to price levels that were deemed inconceivable a few years ago - roughly a third of industrial companies say they face an existential threat. In response to the crisis, industry has intensified its calls for speeding up the renewables rollout and the ramp-up of a “hydrogen economy.” Close coordination with EU policies will be key to initiating the shift to a climate-neutral manufacturing sector, which many German companies have come to see as an enormous business opportunity. Industry will have to lower emissions from 181 million tonnes of CO2 in 2021 to 118 million tonnes by 2030.

- The economy ministry said that keeping industry in Germany will be a central challenge in 2023 given high energy prices, a loss of competitiveness and a shortage of skilled labour. Safeguarding Germany as an industrial location, establishing frameworks that enable industry to stay and manufacture in the country and ramping up the procurement of goods for future markets will be central to political debate and attention next year, economic affairs minister Robert Habeck said. The government bets heavily on the electrification of industrial processes and the use of green hydrogen to lower emissions.

- German industry said it plans to stick to its decarbonisation targets despite the energy crisis, because they are “in the very own interest of companies.” Industry association BDI listed six key measures to achieve industry climate targets: Boosting renewable power; the hydrogen economy; carbon contracts for difference (CCfDs); rail transport and charging infrastructure investments; building renovations; and circular economy value chains.

- The government is in the process of setting up the legal and financial preconditions to enable CCfDs to compensate companies for the higher operating costs of low-emission investments.

- Hydrogen and other decarbonisation technologies are set to feature prominently at the Hannover Messe, one of the world's largest industry fairs, in late April.

Buildings

Decarbonising the building sector while ensuring housing remains affordable and constructions are performed in line with biodiversity protection measures will be key not only in 2023 but in many years to come. With Germany missing national emission reduction targets in the buildings sector in the last two years, both the climate-friendly construction of new buildings and the renovation of old ones will be high on the agenda for the now one-year-old ministry of housing, urban development and building led by Social Democrat (SPD) Klara Geywitz.

- An "ambitious" energy efficiency law with binding targets in the building sector was announced by chancellor Scholz, but the draft law was temporarily shelved following pushback from the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP). The traffic light coalition hopes to pass the draft law by the end of January.

- Germany relaunched its sluggish smart meter roll-out to help it better integrate renewables, electric cars and heat pumps in the grid. Additionally, the economy ministry has proposed to make smart meters mandatory for large and medium-sized companies, and expects approval of the plan in the first quarter of next year. So far, the installation of the devices has been slow due to complex approval and certification procedures.

- Electrifying the heating sector is another key to achieving the country’s net-zero targets. A shareholder alliance was set up to speed up the roll-out of heat pumps, setting the target of installing 500,000 new units annually from 2024 onwards. Therefore, next year will see regulatory frameworks amended to make this possible, which includes addressing supply chain problems and skilled worker shortages.

- The new tiered CO2 cost split between landlords and tenants, agreed towards the end of the year, will come into effect in 2023. Under the new model, the less energy-efficient a building is, the more landlords will pay for CO2 emissions caused by the combustion of fossil fuels. The price breakdown aims to relieve tenants from rising CO2 costs and incentivise landlords to renovate buildings and make them more energy-efficient.

- Energy efficiency in new buildings is also being driven by reforms to the Building Energy Act (GEG) from the start of 2023. Efficiency targets for building renovations have been raised for next year andfurther reform planned for 2023 will raise those further and stipulate that every newly installed heating system must run on 65 percent renewable energy, a requirement from 2024. The construction of solar systems on commercial buildings should also become mandatory and, for private households, rooftop solar PV systems are to become "the rule".

- Municipal heat planning might become mandatory for municipalities, but so far the government hasn’t presented key points or draft bills.

- Sustainable urban development, together with cities’ resilience and transformation, will be high on the building ministry’s agenda following one of the hottest summers since records began. Urban development is to focus on climate protection and on the adaptation of cities to climate change.

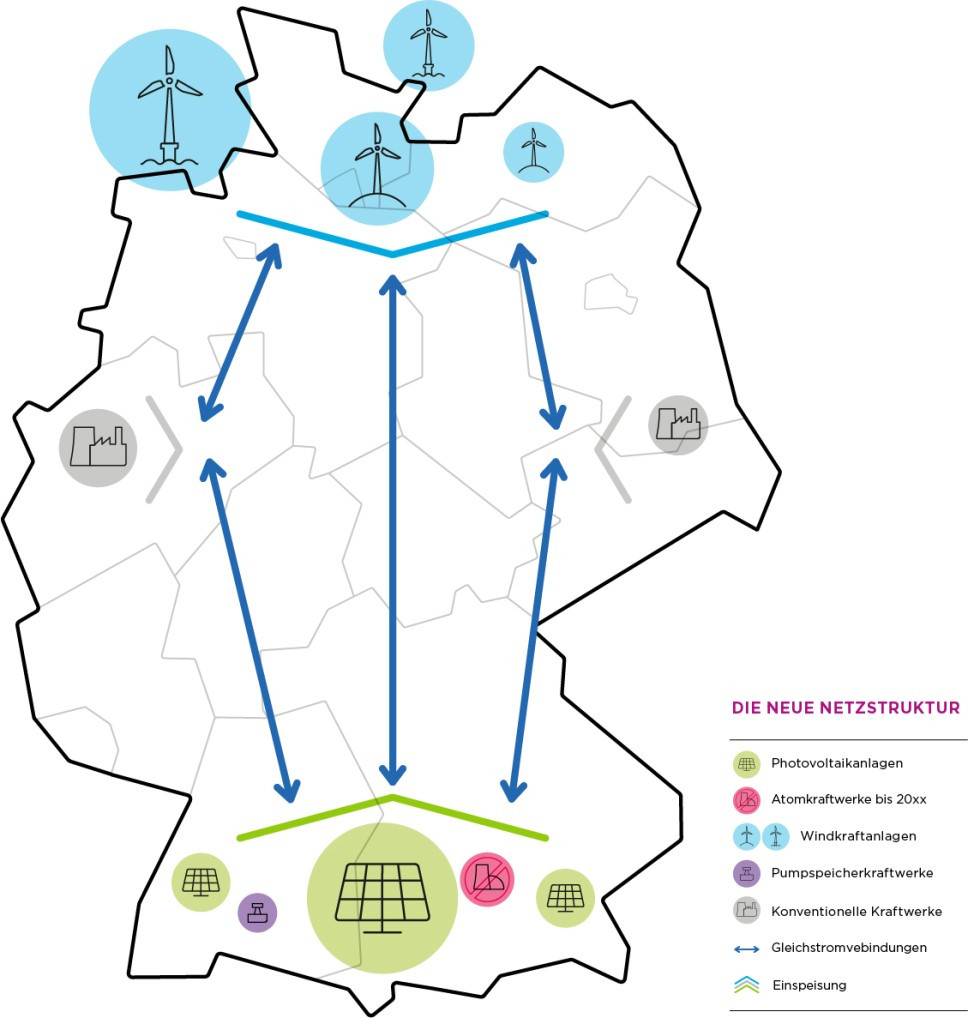

Power grid and power market

As the share of renewable energies grows in Germany’s energy mix, the country needs to upgrade its grid so it can deal with the new challenges brought by fluctuating renewable power production. Additionally, given that Germany’s renewable capacity is mostly in the north but much energy is needed in the industrial south, a modern grid is key together with more evenly distributed renewable installations. Keep an eye out on:

- The Energy Industry Act, Grid Expansion Acceleration Act and Federal Requirements Plan, all of which aim to speed up the grid expansion and increase the level of grid capacity utilisation and load flexibility. The government hopes that the speedy LNG terminal opening sets a new pace for infrastructure modernisation. This includes grid expansion, especially when projects involve several federal states or cross national boundaries.

- Alongside European Commission plans to propose a revision of the EU’s internal electricity market rules in the first quarter of 2023, the German government promised in its coalition treaty to work out a new power market design, with input from a stakeholder group (“Plattform Klimaneutrales Stromsystem”). The platform is set to begin its work with delay in the first quarter of 2023 and is expected to retain the energy-only market but supplement it with capacity mechanisms, according to Tagesspiegel Background. A power market reform has also been a frequent demand by the energy industry. The energy transition monitoring commission plans to publish an analysis in January

- By May 2023, TSOs will make available the new grid development plan, which for the first time includes full climate neutrality in 2045 in its scenarios.

Agriculture and forestry

The agriculture sector has been long thought to be “hard to decarbonise,” as food production comes with unavoidable emissions. However, the role that farmers play in achieving climate goals is increasingly being considered. With Cem Özdemir (Green Party) leading the agriculture ministry for a year, a great emphasis is being placed on climate protection and resilience, also because climate change poses a great threat to agriculture and its ability to secure food production in the future.

- A new nutritional strategy aims to reduce the environmental impact of food, from production to consumption and waste. Measures to create better framework conditions that make healthier and sustainable nutrition easy are meant to be identified throughout next year, with the government hoping to adopt the strategy by the end of 2023.

- Greater emphasis is to be placed on the services farmers can provide for environmental and climate protection under the new funding period of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). A new ‘national CAP strategic plan monitoring committee’ has been set up to ensure that the CAP becomes an even stronger core instrument for the sustainable transformation of agriculture. The CAP will aim to protect natural resources, secure food supply in the future and make better use of the potential of rural areas.

European climate and energy policy

European countries will continue to deal with the energy crisis throughout next year and seek sufficient gas supply on world markets, while boosting renewable energy and key technologies, such as heat pumps. In mid-December 2022, European institutions found a deal on key Fit for 55 elements, such as the emissions trading systems and a carbon border tax, which must now be put into law and implemented.

- Sweden takes over the presidency of the Council of member state governments and is thus instrumental for the progress of key European Green Deal legislation. The Swedish priorities were presented on 14 December 2022: security, resilience, prosperity, democratic values and the rule of law.

- The biggest climate debate of 2023 could be the reform of the EU’s fiscal rules, Manon Dufour, head of the think tank E3G's Brussels office, told Clean Energy Wire.

- The European Commission aims to present a proposal to reform the EU electricity market in the first quarter of 2023.

- Keep an eye on whether or not countries show solidarity with each other in the energy crisis – especially over winter.

- Preparations for the next EU legislature will ramp up throughout 2023, with the elections taking place in 2024.

International climate and energy policy

The development of the global energy landscape under the heavy influence of Russia’s war against Ukraine will continue to be a key issue.

- A key question in 2023 will be the extent to which countries will manage to avoid creating stranded assets and take advantage of the synergies offered by renewables with regard to energy security and emission reduction, Marian Feist, researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), told Clean Energy Wire.

- The climate change conference COP28 is set to take place in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) between 30 November and 12 December. It will be the first formal assessment of worldwide progress since the Paris Agreement came into force – the so-called “global stocktake.”

- The UN secretary general will convene a ‘climate ambition summit’ in 2023, ahead of the conclusion of the stocktake at COP28 next year.

- Loss and Damage Fund: Following the initial agreement at COP27, the decisive details must now be negotiated.

- Following Indonesia and Vietnam, the G7 and partner countries have yet to agree two of the just energy transition partnerships (JETP) decided during Germany’s 2022 G7 presidency: India and Senegal. India will hold the G20 presidency in 2023, so there is a perfect opportunity.