Q&A: Why is Germany phasing out nuclear power - and why now?

***This Q&A is part of a whole package on Germany's nuclear exit, which you can find here.***

Content

- Did Germany reconsider its nuclear phase-out in light of the energy crisis?

- How did the nuclear phase-out come about in Germany?

- Why the nuclear phase-out was the enabler of the energy transition

- Why isn’t Germany phasing out coal before nuclear?

- What do different stakeholders in Germany think about the nuclear exit?

- Will Germany emit more CO2 because of the nuclear phase-out?

- How does Germany want to make net-zero happen without nuclear?

- Why doesn’t Germany get an energy system with both renewables AND nuclear?

- Will Germany become dependent on (nuclear) power imports from abroad?

- What’s more expensive – renewables or nuclear?

- Shouldn’t Germany – like other countries – embrace and support the use of new small modular reactors?

- What is different in Germany compared to other countries in Europe which embrace nuclear as a CO2-free solution?

1. Did Germany reconsider its nuclear phase-out in light of the energy crisis?

Shortly before the originally planned end date for nuclear power in Germany in December 2022, the European energy crisis fuelled by Russia's war on Ukraine led to a resurgence of the debate about the technology's future in the country. Proponents of nuclear power called for completely re-evaluating or at least delaying the exit at a time when the loss of gas supplies from Russia led to widespread concerns about energy security, and quickly rising energy prices put a strain on households' and companies' budgets.

The extent to which nuclear power could help in the crisis was hotly debated, as only a small share of gas is used in power production (it is mostly used for heating buildings, and in industry). Flexible gas power plants are often only used to provide electricity during certain peak demand periods, something the nuclear plants are not designed to do. However, some stakeholders emphasised that every kilowatt hour of saved gas counted, and others argued that nuclear could be necessary to provide grid stability during winter.

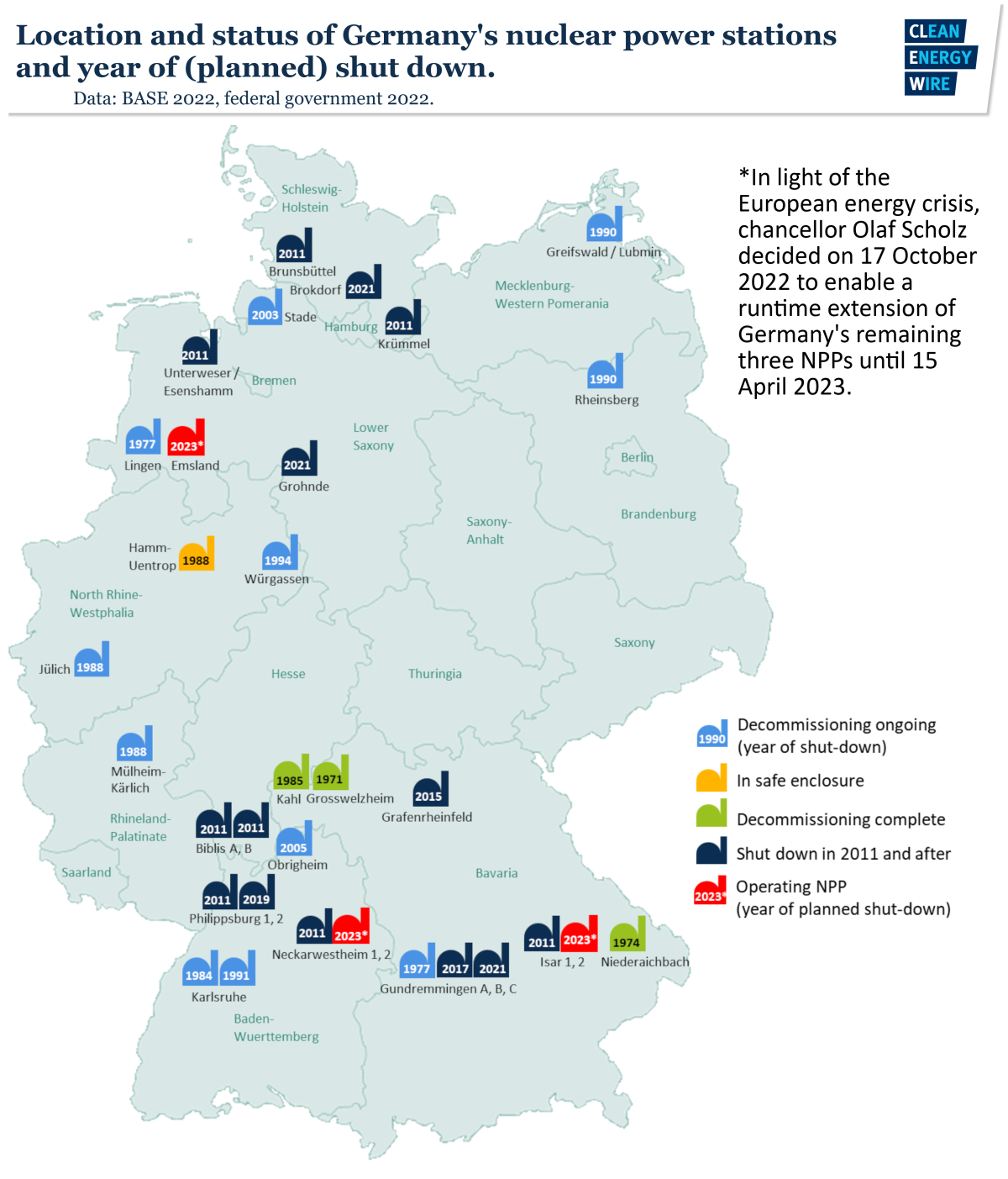

The government commissioned a so-called “stress test” in the summer of 2022 to see whether it would make sense to let the remaining reactors run several months longer to ensure grid stability during the winter of 2022/23. It found that a limited runtime extension could make sense for supporting electricity production. Chancellor Olaf Scholz ultimately decided that the three remaining nuclear plants in the country receive a runtime extension of about three months, until 15 April 2023, to act as a backup during the crisis. The government later ruled out any further extensions and plant operators said that letting the plants run longer would not be possible from a technical point of view, even if this was desired politically.

The environment ministry (BMUV), which is also responsible for nuclear safety, confirmed in late March that nuclear power generation ends on the planned date, arguing that this will not affect the country's energy supply security in the winter 2023/2024. However, it added that dismantling the reactors and deciding on a final repository for radioactive waste are challenging tasks that will likely take several more decades to complete, while the many ageing reactors in operation in neighbouring countries continued to pose a severe safety risk for Germany and for Europe as a whole.

2. How did the nuclear phase-out come about in Germany?

The conviction that nuclear power should not be part of Germany’s energy mix has a long history and is deeply rooted in German society. After years of protests against nuclear power station projects in several locations, and fuelled by the accident at Three Mile Island (U.S.) in 1979 and the Chernobyl catastrophe in 1986, the anti-nuclear movement resulted in no new commercial reactors being built in Germany after 1989.

When the Social Democrats and Green Party took over from a conservative government in 1998, they agreed a “nuclear consensus” with the big utilities operating the nuclear station fleet. By giving them certain power generation allocations, the last plant would be closed in 2022.

In 2010, a new conservative government under Angela Merkel amended this agreement, thereby extending the stations’ operating time by eight years for seven nuclear plants and 14 years for the remaining ten. But after the accident in Fukushima, Japan, in March 2011, Merkel’s cabinet reversed course and mothballed Germany’s oldest reactors for three months, before proposing to shut them down for good and phase-out the operation of the remaining nine plants by 2022.

[Also read the factsheet The history behind Germany's nuclear phase-out]

3. Why the nuclear phase-out was the enabler of the energy transition

Individual countries initially had different reasons to commit to climate action, reduce the use of fossil fuels and, in 2015, sign the Paris Agreement which should lead all nations onto a path towards net-zero emissions. For some it was about securing a domestic power supply in the form of renewables. For many, it only became a feasible idea after prices for wind and solar power installations dropped considerably, while others reacted to the brewing climate crisis and international pressure to act.

The starting point of the energy transition in Germany, and with it the idea of climate protection, is the anti-nuclear movement and the closely linked rise of the Green Party at the end of the 1970s. As opposition to nuclear power and support for the Greens grew – resulting in their entry into government in 1998 - so did the general public’s awareness of environmental and climate protection.

"It is true that, at the beginning of the energy transition in Germany, we argued mainly about nuclear power,” Rainer Baake, one of the architects of Germany’s first nuclear exit legislation and former energy ministry state secretary, told Clean Energy Wire. "But in parallel to the nuclear phase-out, we created the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) in 2000. With this law, we wanted to prevent the nuclear phase-out from leading to an increase in fossil power generation and a burden on the climate. In reality, much more has been achieved in the last two decades. Renewables generate much more electricity in Germany today than nuclear power plants did in 2000," said Baake, who is now managing director of the Climate Neutrality Foundation.

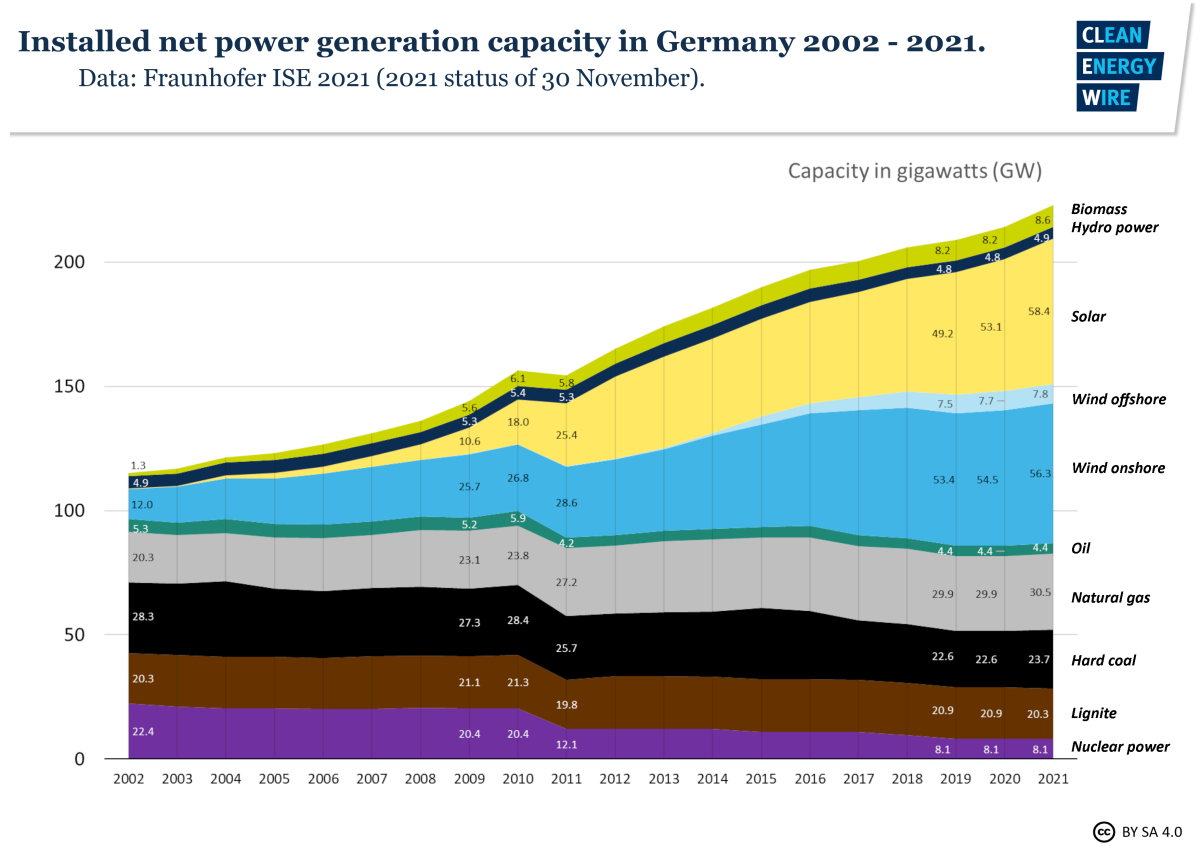

The first Renewable Energy Act, which established a feed-in payment to producers of wind and solar power, initiated a renewables boom, lowered the price for the new technology considerably, and saw the share of renewables in German power consumption grow from 6 percent in 2000 to 46 percent in 2020. This transition in the power supply – known as “Energiewende” – raised the awareness and ambition to also decarbonise other sectors and led to the 2020 decision to phase-out coal power by 2038 at the latest. The new German government wants to move this end-date forward to 2030.

4. Why didn’t Germany phase out coal before nuclear?

Germany is often criticised for phasing out low-carbon nuclear power while its share of CO2-heavy coal in the energy mix remains relatively high. There are several reasons and explanations for this.

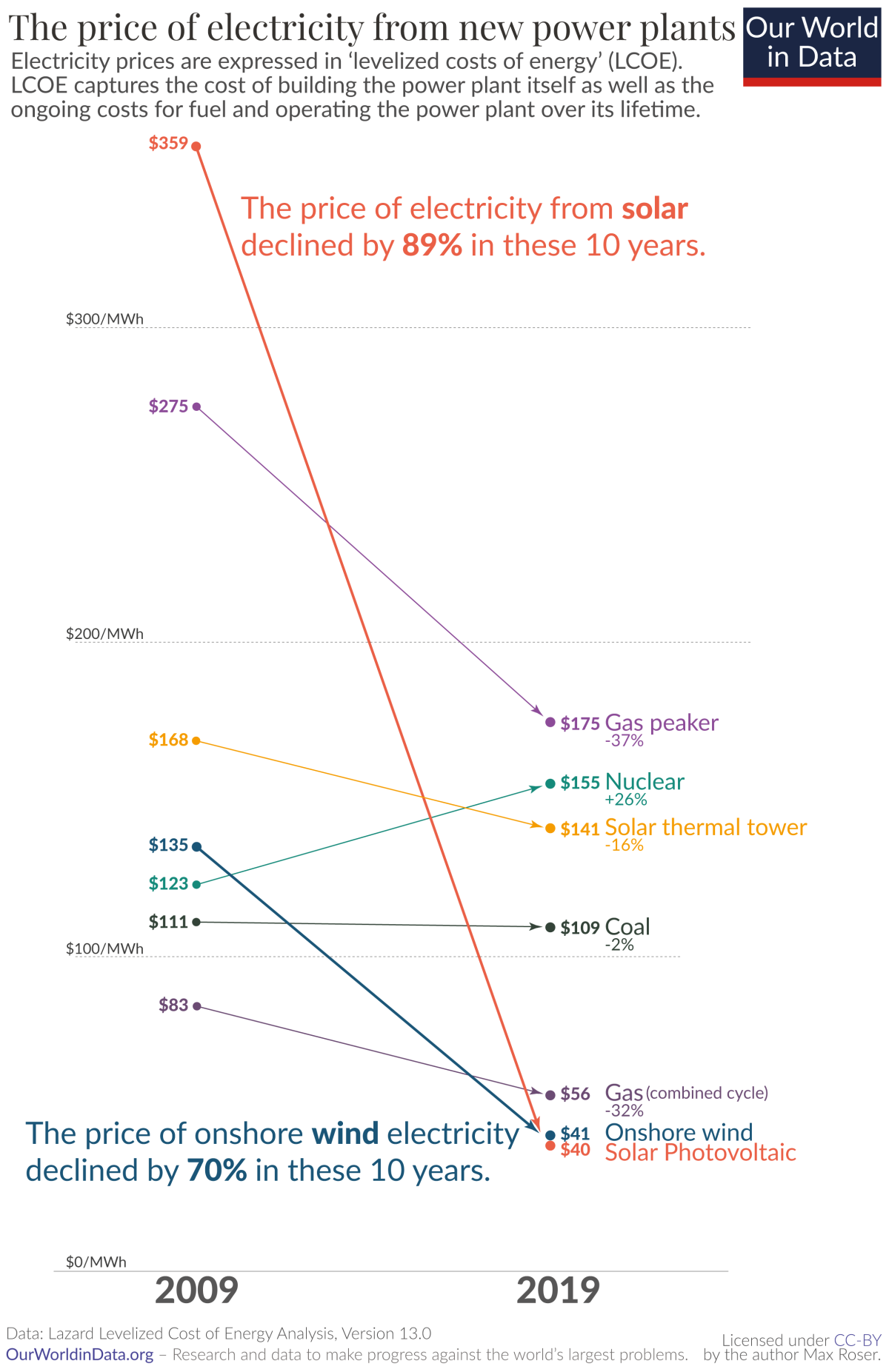

The decision to phase-out nuclear power was also the starting point for decarbonising the country’s power supply, by mainstreaming renewable energies and lowering their prices until they became cheaper than new conventional plants. Compared to most countries – which largely took their coal exit decisions after the Paris Agreement of 2015 (several more pledged to end coal at the UN climate summit COP26 in 2021) – the early 2000s or 2010s would have been an extraordinarily early push to end the use of a historically familiar, domestic, and reliable power source in Germany, at a time when renewables didn’t present such an affordable and secure alternative as they do now.

Since the nuclear phase-out decision of 2000, the share of coal power in Germany’s electricity generation has fallen from 43 percent in 2011 (when 7 nuclear plants went offline) to 23.4 percent in 2020. No new coal power stations have been planned/constructed since 2007.

Nevertheless, it does paint a rather questionable picture if a nation that sees itself as a climate action pioneer still boasts some of the largest power station emitters in Europe. However, Stefan Rahmstorf, Head of Earth System Analysis at Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, points out that “emissions from the energy sector have been cut in half since 1990 […] It's the other sectors which have failed so far to deliver their cuts”.

Campaigning against its fossil plant fleet led to Germany's agreement in 2020 to phase out coal power by 2038. Following the country's decision to pull forward its net zero target date to 2045, the new government said it plans to pull forward the coal exit "ideally" to 2030.

“Germany’s too-slow emission reductions cannot simply be linked to the timing of the nuclear and coal phase-outs," Simon Müller, Director Germany at think tank Agora Energiewende, told Clean Energy Wire. “After the boom years, the government let the renewable markets crash. With a more ambitious renewables expansion, the share of CO2-free power generation could be much higher now,” he said.

Another difference between coal and nuclear: Although keenly embraced by the leading parties in the 1960s, nuclear power was a relatively new phenomenon which didn’t have a strong footing in society and soon got discredited by accidents and protests. Coal mining, on the other hand, has been deeply rooted in several German states for 200 years. It used to have a large – and often proud – workforce with considerable political influence and was often the main employer and economic stronghold of a region. It is (or, in the case of hard coal, was) also a domestically available energy source.

These are among the reasons why it was easier for Germany to initiate the exit of nuclear power before the phasing out of coal.

5. What do different stakeholders in Germany say about the nuclear exit?

Ever since the latest nuclear phase-out was decided by a large majority in the federal parliament (Bundestag) in 2011, the public has remained broadly supportive of exiting nuclear power for good. But the energy crisis has shifted opinion more in favour of nuclear energy, and led many people to consider the phaseout less urgent. Polls in mid-2022 showed a majority in favour of extending the lifetime of the remaining reactors, and shortly before the exit in April 2023, about two thirds of Germans said they were against the imminent shutdown of the remaining three nuclear power plants.

Since 2011, successive German governments have remained steadfast in the phase-out decision despite going through a difficult process of securing the money from reactor operators to ensure their safe deconstruction and storage of radioactive waste, initiating the search for a permanent waste storage facility, and weathering the legal proceedings following the not-quite constitutional compensation regulations in the nuclear exit law. Former SPD environment minister Svenja Schulze said at the 2021 anniversary of the Fukushima accident that “nuclear power is neither safe nor clean” and could not be a part of a low-carbon power production. Angela Merkel reiterated in her last summer press conferences before the end of her chancellorship, that “the nuclear phase-out is the right thing to do for Germany”, adding that this could be seen differently by other countries and activists who push for climate neutrality. “I don't think nuclear energy is a sustainable form of energy in the long term,” Merkel said.

The tripartite German government of Social Democrats (SPD), Green Party and Free Democrats (FDP), which took office in December 2021, wrote in its coalition treaty “we stand by the nuclear phase-out”. The (Green Party) environment minister Steffi Lemke said in December 2021: “Nuclear power would make our energy supply neither safer nor cheaper. A technology that has no solution for the disposal of toxic waste cannot be sustainable." Climate and economy minister Robert Habeck (Green Party) said on 28 December: "The nuclear phase-out in Germany has been decided, clearly regulated by law and is valid. Security of supply in Germany continues to be guaranteed. Now it is important to consistently push ahead with the transition of our energy supply." In light of the energy crisis, FDP ministers came out in favour of extending nuclear power in Germany, but the government as a whole decided to only grant a very limited extension.

When looking at the individual political parties, both Green Party and SPD are against using nuclear power. In the conservative parties (CDU/CSU) there are voices who say that Germany should have phased-out coal before nuclear and not both at the same time. Only days before the final switch off, Opposition leader Friedrich Merz (CDU) called the phaseout a "black day for Germany." The right-wing populist AfD is also in favour of new nuclear power stations.

Energy utilities and operators of Germany’s remaining nuclear power stations are adamant that there will be no additional extension of the reactors’ runtime. The large German utilities have – after years of struggling – embraced a renewable future and the planning security that the end of nuclear power gives them. They also point out that all the legal (compensation) issues of the nuclear phase-out have been resolved, operating licenses are scheduled to expire and difficult to re-obtain, contracts with suppliers and other service companies have been terminated, staff has been reassigned and there is no longer enough fuel.

6. Will Germany emit more CO2 because of the nuclear phase-out?

Some climate activists, researchers, and the pro-nuclear groups argue that if Germany had decided to reduce coal power consumption before it stopped using nuclear power, it would have prevented CO2 emissions. “From a pure emissions perspective, it was always a questionable idea to shut down German nuclear before the plants have reached the end of their lifetime,” Hanns Koenig, head of commissioned projects at Aurora Energy Research told Bloomberg.

The Federal Environment Agency uses the following emission estimates: Onshore wind 10 grams CO2equivalent per kilowatt-hour, solar PV 67g CO2eq /kWh, nuclear 68g CO2eq /kWh, natural gas 430g CO2eq /kWh, lignite more than 1kg CO2eq /kWh.

Pro-nuclear activists Rainer Moormann, who used to be a physical chemist at the Jülich Research Centre, and Anna Veronika Wendland - from the Herder Institute for Historical Research on Eastern Central Europe in Marburg - argued in 2020 that leaving the last six nuclear power stations running would have enabled Germany to shut down all of North Rhine-Westphalia’s lignite plants – by reversing the decision to shut down the last six reactors in 2021 and 2022 and let them run until the end of the decade Germany’s total CO2 emissions could be reduced by 10 percent, they estimated.

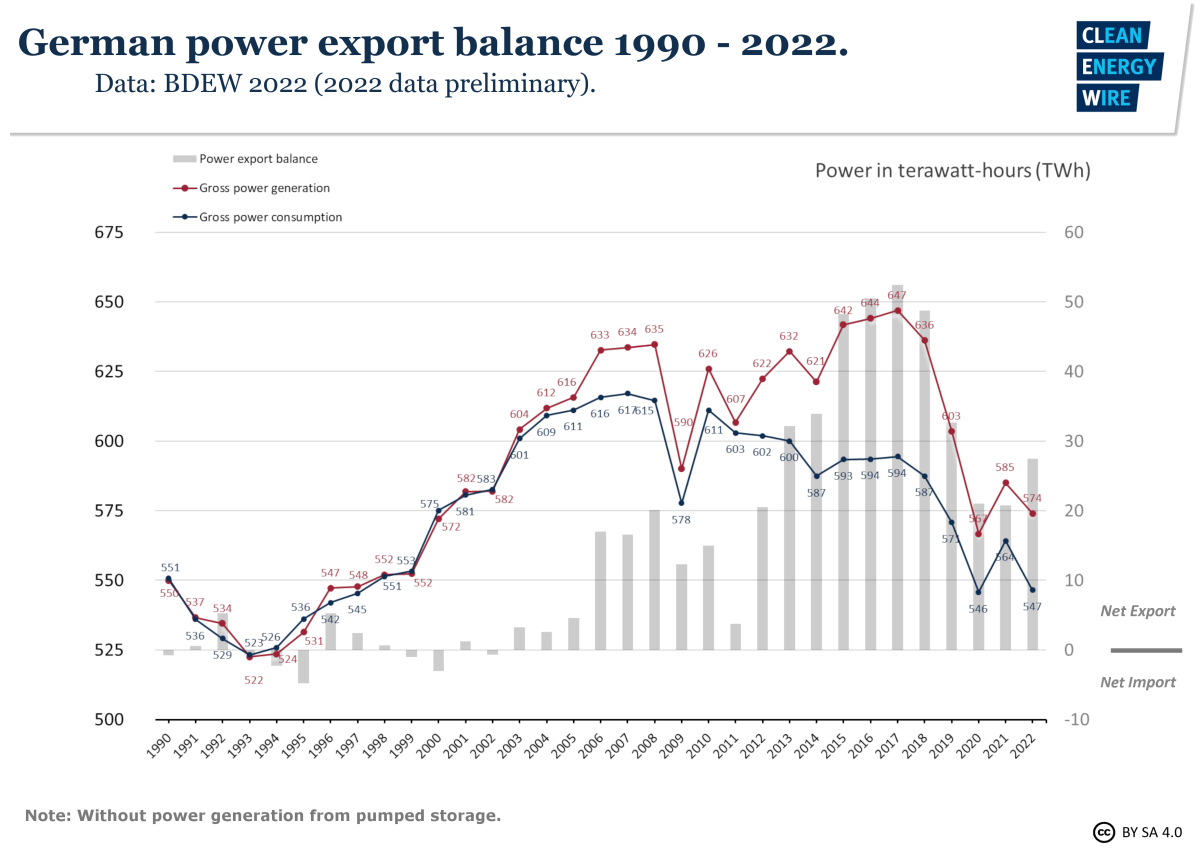

Economists of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) conclude in a recent paper that “the decline in nuclear power will temporarily lead to a higher use of fossil energies and imports, which will increase CO2 emissions in the short term. However, these should be quickly reduced by the accelerated expansion of renewable energies.” In the short term, nuclear power will indeed be substituted by fossil power plants and via imports. Imports increase by 15 terawatt-hours (TWh), emissions will be around 40 million tonnes CO2 higher, according to the DIW. Other research shows that in the context of the overall cap of the European Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), rising emissions in Germany would be compensated by lower emissions in other countries, therefore keeping overall emissions stable and, at the same time, seeing a slight rise in the price for CO2 allowances.

Overall, renewables are now better placed to prevent carbon emissions than nuclear, physicist Amory B. Lovins, adjunct professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University concludes in an op-ed for Bloomberg Law: "Renewables swelled supply and displaced carbon as much every 38 hours as nuclear did all year. As of early December, 2021’s score looks like nuclear –3 GW, renewables +290 GW. Game over."

7. How does Germany want to make net-zero happen without nuclear?

Germany’s energy transition in the electricity sector has turned into a comprehensive plan to decarbonise the entire economy and reach net-zero greenhouse gases in 2045. With nuclear power and coal out of the picture by the end of the decade, the new government – which is adhering to the previous government’s climate targets – is putting the focus on renewables growth. Its aim is to reach a share of 80 percent renewables in electricity demand by 2030 (which is envisaged to grow). Several “Germany net-zero” studies have shown that a system based on renewables is possible.

The government acknowledges that a fleet of flexible (and hydrogen-ready) natural gas plants will be necessary to run a stable power system. Between 2019 and 2030, 21 GW of lignite and 25 GW of hard coal capacity will be shuttered, research institute EWI has calculated. Existing over-capacities, new flexibility options, and efficiency - as well as the addition of renewables capacity - will mean that not all of this controllable power plant capacity will need to be substituted, German energy industry association BDEW says. “But an earlier coal phase-out means we will need an additional 17 GW in gas-fired capacity,” BDEW head Kerstin Andreae said. This capacity would not run 24/7. It would instead be used during peak demand hours or when there is little wind or sun.

Germany will have to be even more interconnected with neighbouring countries to exchange (renewable) power in times of low wind and little sun. It will need to upgrade its grid system. To supply power stations and industry, large amounts of hydrogen will be needed and imported.

8. Why didn’t Germany opt for an energy system with both renewables AND nuclear?

Nuclear power advocates portray the technology as a reliable energy source that can help to secure supply during times of little wind and sun. "We need renewables to be complemented by a reliable, 24/7 energy source," said James Hansen, a climate scientist at Columbia University when taking part in a pro-nuclear climate demonstration in Berlin.

But German energy experts have voiced their doubts about whether fluctuating renewables are best complemented by nuclear. At the same time, the unavailability of large parts of France's nuclear fleet in the summer of 2022 due to low water levels in rivers and delays in maintenance works cast doubts on the unshakeable reliability of nuclear reactors. "A climate-friendly electricity system dominated by weather-dependent production from wind and solar plants requires a great deal of flexibility to balance fluctuating supply with fluctuating demand. Nuclear power plants are technically and operationally designed for production that is as constant as possible. They are the exact opposite of what wind and solar need as partners," former energy ministry state secretary Rainer Baake said.

Simon Müller, of Agora Energiewende, explained: “Nuclear and renewables are cheap to operate once they are built. This means ramping nuclear up and down is not an economic way to provide flexibility for the power system. Indeed, today’s pumped storage and demand-side response was built decades ago to provide flexibility to integrate nuclear power. Having both nuclear and renewables in the same system therefore increases the importance of other flexibility options.”

9. Will Germany become dependent on (nuclear) power imports from abroad?

Critics have called Germany’s decision to turn its back on nuclear energy hypocritical because it would continue to receive nuclear power generated in France or Belgium. Germany has power cable interconnectors with its European neighbours and has been a net exporter of electricity for many years. In addition to its nuclear and coal power generation, it had a growing share of renewable generation which buyers in the internal European power market liked to source because it is cheap. With the nuclear and coal exit, it will lose some of its overcapacities and more often import power from its neighbours – who also generally have a growing renewables share – but it won’t be alone in doing so. France imported large quantities of electricity from Germany in the past years to keep its nuclear-based power system stable.

In the future European electricity system, it is going to be “completely normal to exchange electricity continuously and dynamically with neighbouring countries”, Simon Müller said. For example, the wind parks of Europe will source power from the same low-pressure system as it moves across the continent, with the windiest country supplying the others before the next one takes over that role and so on.

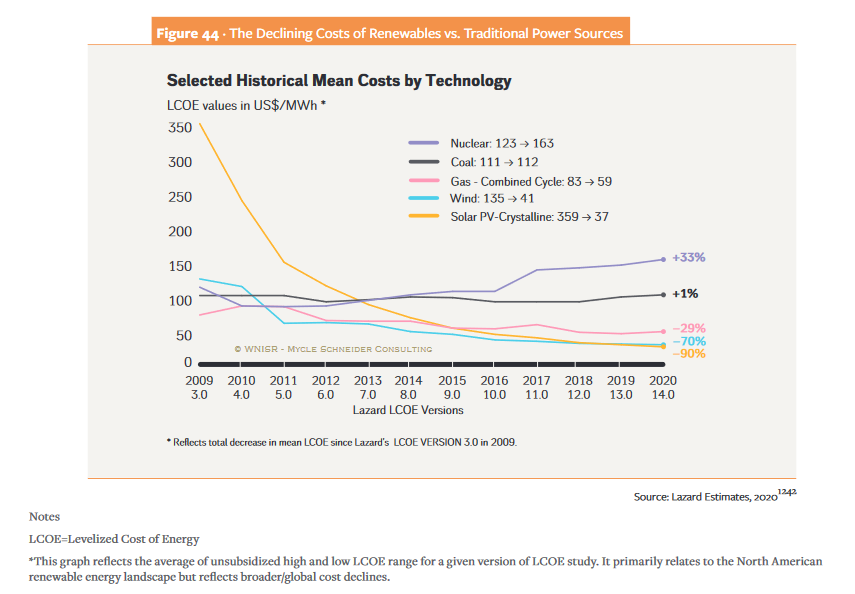

10. What’s more expensive – renewables or nuclear?

One of the reasons why it is an obvious choice for Germany to make wind and solar its main power source rather than nuclear, is that new renewable installations have become cheaper than all other electricity sources – especially where a CO2 price is applied.

According to the World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2021 and Institute for Applied Ecology (Öko-Institut), the energy costs for nuclear power generation are currently 15.5 cents per kilowatt hour, compared to 4.9 cents for solar energy and 4.1 cents for wind power.

The British government has given a price guarantee of 11 cents per kilowatt-hour for 35 years to the nuclear power plant project Hinkley Point C. In Germany, feed-in tariffs for onshore wind and solar PV are between 6-7 ct/kwh or, in some tenders, even lower. Offshore wind parks are now being built without any government support.

New reactor projects often turn out to be much more expensive than envisaged. The costs for a new “Evolutionary Power Reactor (EPR)“ in Flamanville, France, have risen from 3.4 billion to more than 19 billion euros, while the project will likely take at least 11 years longer than planned. Similar price hikes and delays have occurred in the UK, Finland and the U.S..

“Nuclear technology has had negative learning rates, which means that new projects became more expensive instead of cheaper. If we take current investment costs as a basis, then it is clear that the cheapest power system is one that is fully based on renewables,” Simon Müller said. The global market situation shows that renewables dominate investments. The 2050 long-term projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA) see nuclear energy supplying about 10 percent of electricity. “For the transformation, we need to thus look to renewables,” Müller said.

As many new nuclear projects also take considerably longer to construct than planned, the Öko-Institut concludes that it would also be faster to build a system based on renewables.

11. Shouldn’t Germany – like other countries – embrace and support the use of new small modular reactors?

Using a large fleet of small modular reactors (SMR) to secure climate neutral electricity supply in the future - as proposed by billionaire and philanthropist Bill Gates – has been hailed as a climate change solution. In Belgium, which is set to shutter its two remaining nuclear power stations by 2025, the government agreed to invest 100 million euros in the research on SMR.

SMR proponents claim that, once produced in bulk, these small plants are cheaper and safer thanks to advanced reactor designs and can be operated with converted short-lived radioactive materials, solving the waste problem. But two assessments commissioned by the Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management (BASE) have found that these tens of thousands of small reactors would carry enormous risks with regard to the proliferation of weapons-grade materials and will probably never be as cheap as their advocates say.

12. What is different in Germany compared to other countries in Europe which embrace nuclear as a CO2-free solution?

Germany not only has strong public support for, and a long history of, anti-nuclear sentiment, it also has only 6 percent of nuclear left in its power mix. Leaving it behind entirely is therefore a more obvious and easy decision than for other countries, such as France, where the share of nuclear power in domestic generation stands at 70.6 percent, but also in Bulgaria with 40.8 percent, in Sweden with 29.8 percent (in Spain: 22.2%, Russia at 20.%, United States at 19.7%, UK 16%, all in 2020).

Historians also explain the different attitude towards nuclear with the different reactions to the Chernobyl accident, which was felt much closer and more threatening to Germans compared to French or UK citizens. Another explanation for Germany’s sensitivity to nuclear power is that early on, the post-war critique of nuclear weapons was linked to the civilian use of nuclear fission. (A second wave of the German peace movement in the 1980s would also bolster a younger generation’s resistance to nuclear power.)

And even if there are people who make a case for nuclear for climate protection reasons, the exit has now proceeded too far to be reversed, and there is simply no influential political power that would consider re-opening the painful, decade-long debate on nuclear power that has finally been put to rest.