After the phase-out: Germany grapples with nuclear legacy as waste challenge remains

As the last reactors are shut down, the future of nuclear power in Germany is now likely to be dominated by the long and arduous process of dismantling all the country's reactors and deciding on a final repository, where radioactive waste can be stored for thousands of years.

“Decades of challenges now lie ahead of us until we have safely and responsibly disposed of the nuclear legacy,” environment minister Steffi Lemke said days before the last reactors were to be shut down. Three generations have benefitted from nuclear power use in Germany, but about 30,000 generations will be affected by the ongoing presence of nuclear waste, she said.

Types of radioactive waste

Radioactive waste in Germany comes mainly from the operation, decommissioning and research surrounding nuclear power plants (95%). The waste is categorised by the level of radioactivity and the amount of heat it emits – which is important when deciding on a final repository.

Materials are often classified according to their low, intermediate or high level of radioactivity. However, Germany aims to store all types of radioactive waste in deep geological formations. Thus, the decisive factor is not the level of radioactivity, but rather the heat generated during radioactive decay, says the Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management (BASE). Radioactive waste is divided into heat-generating waste and waste with negligible heat generation. Heat-generating waste is made of up high-level waste, as well as part of the intermediate-level waste. It includes, in particular, waste from reprocessing and spent fuel elements.

Other countries have other ways of categorising radioactive waste.

Heat-generating waste (mostly high-level waste)

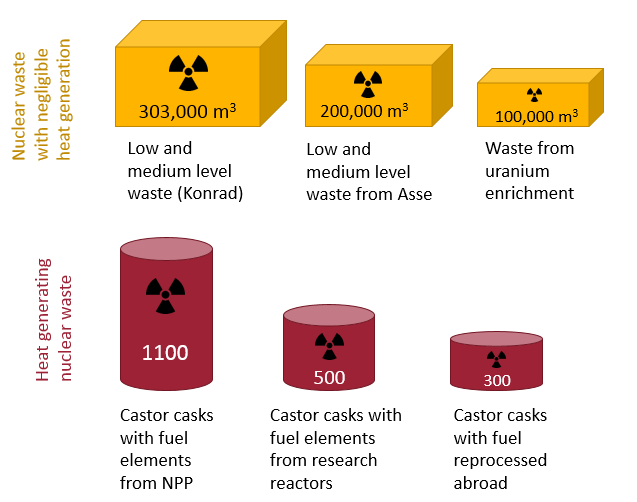

The country will have to store 1,900 large containers, or around 28,100 cubic metres (m3), of high-level radioactive waste by 2080 (Figure 1), when all its nuclear power stations and many research facilities will have been finally decommissioned and the fuel elements treated at other facilities.

The extended lifespan by several months of the last nuclear reactors in 2023 will not lead to additional high-level waste, the environment ministry said.

High-level radioactive waste needs to be securely stored for several million years until its harmful radioactivity fades. Scientists (nuclear semiotics) are even wondering how future generations of human beings could be warned against the dangerous waste, because languages and symbols may have changed entirely and storage places might be forgotten hundreds of thousands of years from now.

Heat-generating waste accounts for only five percent of Germany’s radioactive refuse, but is responsible for 99 percent of the radiation. It is currently held at temporary storage facilities near the nuclear power stations and in central interim repositories in Ahaus (North-Rhine Westphalia), Lubmin (Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania) and Gorleben (Lower Saxony).

Waste with negligible heat generation (low and medium-level waste)

By 2080, Germany will have to store some 620,000 m3 of low and medium-level nuclear waste with “negligible heat generation” (Figure 1). This waste is largely made up of disused plant components and components such as pumps and pipelines, ion exchange resins and air filters from waste water and exhaust air treatment, contaminated tools, protective clothing, decontamination and cleaning agents, laboratory waste, sealed radiation sources, sludges, suspensions or oils.

A total of 303,000 m3 of the 600,000 m3 of low and medium-level nuclear waste are to be stored in a final storage facility in the Schacht Konrad retired iron ore mine near Salzgitter. The repository is under construction and – after substantial delays also due to protests – is scheduled to be loaded from 2027. The federal government aims to complete this process within 40 years, the government said in the “national disposal programme” of August 2015. It remains to be seen whether the facility will go into operation at all. There are calls for withdrawing the permits, and the state government has said it aims to have a decision by the end of 2023, if possible.

There are currently a multitude of interim storage facilities for radioactive waste with negligible heat generation situated all over the country, near research facilities or operated by the nuclear industry as well as state collection depots. Many interim storage locations house both high-level and low and medium-level waste.

Finding a final repository for high-level waste a drawn-out process

Germany’s official process for deciding a final repository for high-level radioactive waste is more than a decade old. After a new “law on finding and choosing a nuclear waste repository” was passed in 2013, the environment ministry set up an expert commission on how the search for a final repository for heat-generating waste is to be administered. The law said that the search would have to end in 2031. Germany would be considered a “blank map” when it comes to finding a final repository for the highly radioactive waste, then environment minister Barbara Hendricks said at the time. The location could be anywhere, provided the geological rock formation for an underground repository is favourable.

The expert commission presented its final report in July 2016, sticking to these general parameters. The search procedure would focus on possible storage sites in rock salt, clay rock and crystalline granite. It would thus also include the salt mine at Gorleben, where explorations had already begun but were terminated amid large protests from citizens (see below).

Nuclear waste is to be stored for one million years in the final repository, but should be retrievable for the first 500 years, the commission suggested. This is in case a treatment is found to reduce radioactivity earlier (transmutation). The commission, made up of parliamentarians, scientists and NGOs, agreed on a general export ban on nuclear waste.

Little trust, strong local opposition

The commission's work showed that finding the right site is a difficult challenge as no community or town in Germany is particularly keen on living next to a cemetery for contaminated waste, Hendricks said. Bavaria’s government, for example, continued to say that there are no suitable rock formations to be found in the state. And the residents of Salzgitter, near Schacht Konrad, worry that the nearby repository would be extended to house even more than the planned 303,000 m3 of low and medium-level waste. The state of Lower Saxony only agreed to the 2013 site selection law on the condition that investigations at the Gorleben salt mine were stopped and no further nuclear waste containers were sent to the interim storage facility nearby.

Security concerns at existing facilities for waste with negligible heat generation at Morsleben and in the old salt mine Asse, which will cost several billion euros to be fixed, have undermined the trust in the safety of nuclear waste repositories. The situation is particularly dire at Asse, where over 200,000 m3 of low and medium-level waste must be retrieved from unstable mine shafts partially flooded with groundwater, causing concerns that radioactive elements could contaminate the drinking water. Getting the leaking radioactive barrels, which were deposited in 1967, out of Asse is set to start in 2033. It is not clear where the Asse waste will then be stored.

Search for final repository could drag into 2070s

With the expert commission’s input, Germany’s parliament, in March 2017, adopted a bill to authorise the search for a final repository. The law states that the public would be “extensively involved” through “transparent participation procedures” before the search’s planned conclusion in 2031.

The main body in charge of conducting the search is the Federal Company for Radioactive Waste Disposal (BGE), which prepares the reports and conducts the stakeholder participation events. It is supervised by the Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management (BASE), which reports to the environment ministry.

The BGE, in 2022, wrote a discussion paper for the environment ministry about the timeline of the search. It said there are too many unknown factors to be able to say when the search could be finalised, but it would certainly take longer than 2031. BGE wrote that depending on how many regions would be evaluated and to what extent underground exploration would take place and how long it would take to get the necessary permits, a location could be decided sometime between 2046 and 2068.

The BGE paper led the government to say that 2031 was no longer a realistic target year. “According to [the BGE paper], the procedure cannot be completed by 2031, taking into account the high requirements for the selection of the site with the best possible safety,” said the environment ministry. It said it would enter into talks with both BGE and BASE about the conclusions that would have to be drawn.

Then, in summer 2024, German media wrote about a report by the Institute for Applied Ecology (Öko-Institut), commissioned by BASE, which said that a decision on a location can be expected in 2074 at the earliest under ideal conditions. However, the environment ministry said the report did not take into consideration significant progress in efforts to shorten the search, for example by saving time on long exploration periods.

Details of the search

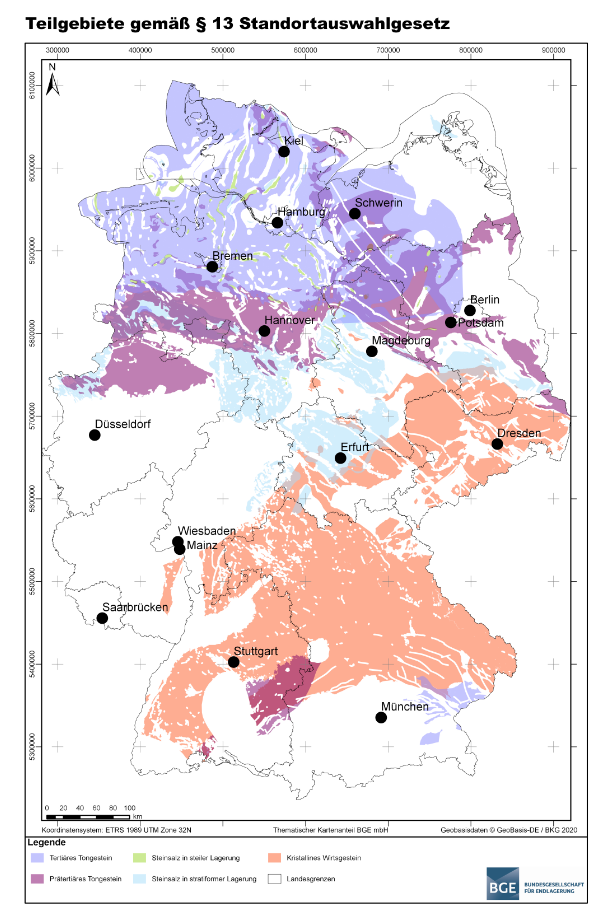

The BGE had to follow the rules set out by the Site Selection Law of 2017 and the accompanying regulations. Its first task was to prepare the “Interim report on sub-areas” (Zwischenbericht Teilgebiete) that devises a first map of possible locations for the final waste disposal site. This report was presented on 28 September 2020.

To arrive at the interim report, the BGE collected existing geological data from the states and used it to exclude unsuitable areas by looking at a set of criteria:

Exclusion criteria: The area may not be prone to volcanic activity, earthquakes or have been damaged by mining activities.

Minimum requirements: The future site of the repository must be located in either salt rock, crystalline rock or clay rock. The covering rock layer above the storage area must be at least 300 metres thick. The surrounding rock must be at least 100 m thick. The storage area must be of a certain size that also allows for retrieving the waste should it become necessary. No water may be able to enter the repository. All these criteria will have to hold true for one million years.

Geo-scientific criteria (to differentiate between areas that are equally suitable under the first two sets of criteria): The surrounding rock must be able to dissipate heat and keep radiation from getting out. The chemical composition of the rock may not interfere with the waste containers.

Next, the BGE will make a suggestion as to which of these regions should be further explored (above ground). It has said it will present its decision by 2027, with annual interim reports along the way.

The federal parliament (Bundestag) and the chamber representing the states (Bundesrat) will decide if the BGE’s recommendation is valid. If this is the case, surface exploration (including exploratory drilling) will begin, followed by another decision by Bundestag and Bundesrat identifying regions to be explored further by building mines for underground exploration.

The BGE will then propose a location for the final repository, which will become law if Bundestag and Bundesrat agree.

Storing the waste in its final destination to last “well into the next century”

After a site decision is made, the final repository for heat-generating waste must be built, which is scheduled to take about 20 years, according to current plans. Only then can the first containers with used fuel elements be deposited.

The process of transporting and storing thousands of casks in the final repository will then take decades more.

The experts from the parliamentary storage commission said that the loading and sealing of the repository could be expected to last “well into the next century.”

Search for a final repository in other countries

Germany is not alone in its search for a final repository. Some examples:

Finland will soon be home to the world’s first permanent site for high-level nuclear waste. A final licence for waste disposal at the Onkalo facility is expected to be issued in 2024, public broadcaster Yle said. A researcher told the radio station that Finland's decision making about the final disposal site has progressed more smoothly than in other countries, also because the low population density is more favourable.

France has had a research laboratory in the Meuse/Haute-Marne region for decades and now plans to build a final repository in its vicinity. In January, French implementer Andra (Agence nationale pour la gestion des déchets radioactifs) submitted the construction licence application for Cigéo, the French project for a deep geological disposal facility. Start of storage is planned for 2035-2040. The planned site is located about 120 kilometres from the border with Saarland in Germany.

Switzerland's National Cooperative for the Disposal of Radioactive Waste (Nagra), which was set up by nuclear power plant operators and the government, proposed a repository site north of Zurich, just two kilometres from the German state of Baden-Wurttemberg. The planned repository will accommodate all of Switzerland's radioactive waste and still needs to be approved by the Swiss government and parliament, which will take several years.