Nuclear fusion cannot balance fluctuating renewables - German parliament report

Nuclear fusion power plants are unlikely to be a suitable supplement to fluctuating wind and solar electricity generation, according to a scientific report for the German parliament. Future use of the technology will only make sense in continuous operation for technical and cost reasons, for example for hydrogen production, said the report by the parliament’s office of technology assessment (TAB).

“In order to compensate for the fluctuating feed-in of solar and wind power, quickly controllable power plants with low investment costs are required,” the report concluded. “Fusion power plants will not be able to fulfil this task in the foreseeable future.”

The TAB is an independent scientific institution set up to advise parliament and its committees with impartial analyses on technological developments and their impact on society. Fusion technology could become a topic in Germany’s upcoming election campaign, as both the Conservatives (CDU/CSU) under chancellor candidate Friedrich Merz and the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) push the technology in their election manifestos.

Germany’s former research minister Bettina Stark-Watzinger (FDP) had called nuclear fusion “a huge opportunity to solve all our energy problems” and boosted research with a new funding programme in 2023. But critics warned that enthusiasm for nuclear fusion is a harmful distraction because the technology will be too late and too expensive to contribute to creating a climate-neutral energy system in the coming years and decades.

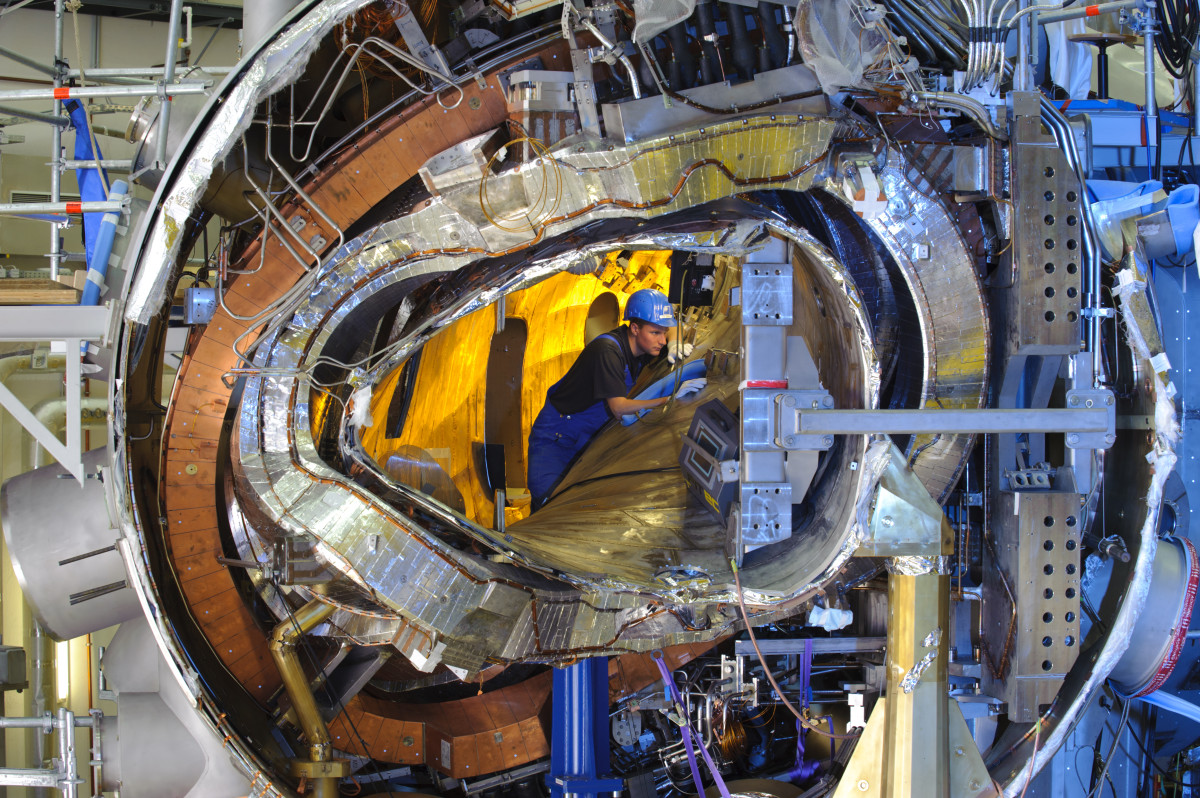

The report for parliament emphasises that fusion power reactors are still a long way away despite recent advances, even though it is based on the assumption that the first step - a plasma that can generate energy - will function reliably in the near future. But many technical hurdles on the way to a proper fusion power plant remain unsolved, the report stresses.

Fusion can’t help to make Germany climate-neutral

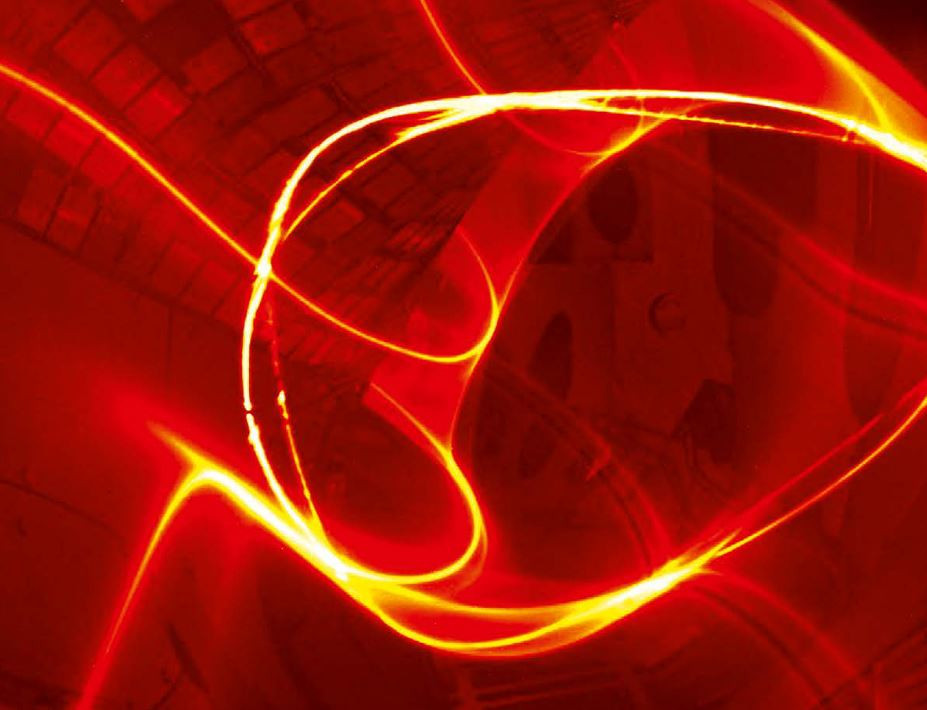

Nuclear fusion research aims to generate electricity using the energy that is released when atoms fuse – emulating the process that powers the sun. Existing nuclear power plants draw energy from splitting atoms in fission reactors. Nuclear fusion has a lower risk potential because there is no danger of an uncontrollable chain reaction and much less radioactive waste.

Germany switched off its three remaining nuclear fission reactors in 2023 – a decision widely criticised internationally, especially given the country’s ongoing coal use. Opposition politicians have repeatedly called for restarting the plants, but this is widely considered unrealistic given that the operators themselves have repeatedly rejected the idea.

Nuclear fusion experts not involved with the report agreed that fusion power plants will not become a reality before 2045, the year Germany aims to become climate-neutral, even under ideal circumstances.

“With significantly higher subsidies and approval procedures suitable for fusion, the first power plant could be connected to the grid around 20 years after the start of an ambitious programme,” Sibylle Günter, scientific director of the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics, told the Science Media Center.

Christian Linsmeier, director of the Institute of Fusion Energy and Nuclear Waste Management at the Jülich research centre (Forschungszentrum Jülich), estimated that, while a first reactor generating electricity could be ready in 20 to 25 years with large-scale policy support, a power plant operating around the clock “will take at least another ten years”.

Researchers from Energy Systems of the Future (ESYS), an initiative of the German Academies of Sciences, also argued last year that, even though nuclear fusion has the potential to provide long-term climate-friendly energy and reduce import dependencies, it cannot contribute to mid-century climate targets because it will take at least 20-25 years until a first power plant can be built. ESYS said further commitment to research “seems sensible”, but warned it must not diminish efforts to make the energy system climate neutral by mid-century.

France better suited for fusion than Germany - researcher

Max Planck Institute’s Günter questioned the report’s finding that fusion power plants will not harmonise well with renewables. “Fusion power plants can interact very well and sensibly with renewables in a future electricity market,” Günter said, adding that they “could provide electricity when needed and produce chemical energy storage such as hydrogen at other times”.

“Furthermore, it is not possible today to make a serious forecast of either Germany's or the world's energy situation in the second half of the century,” Günter said, suggesting that fusion plants could also supply heat for industry, or be used to produce artificial fuels such as hydrogen, run CO2 capture, and desalination plants.

Researcher Linsmeier stressed that, while fusion power plants currently don’t look like a perfect match for Germany’s future energy system, they might be better suited in other countries. “It is a political question as to how our electricity system should be organised in the future,” he said. “In Germany, there is a very specific view that wind and solar should be used for the majority of electricity production.”

Patrick Jochem, who heads the Department of Energy System Analysis at the German Aerospace Centre (DLR), told the Science Media Center that it would “probably be more economical to operate nuclear fusion power plants in countries with existing base load power plants such as nuclear power plants - for example in France”.

The role of nuclear power in Europe’s emissions reduction plans has been a contentious issue for years, with Germany and France emerging as the main opposing forces between two groups of countries aiming to rely entirely on renewable power or to also use nuclear power in a future climate neutral energy system.