Recycling revolution necessary to complete the clean energy transition

For over two decades, debates about renewable power installations and electric vehicles in Germany have generally focused on a single question: how to get more of them on the market? Thanks to a wide array of support schemes and other investor incentives, this question to a large extent seems to have been answered with success – certainly for renewables, whose share in national power production climbed from just over five percent in the year 2000 to about 50 percent in 2020, and lately also for e-cars, which according to transport authorities finally have "entered the mainstream" and are projected to number millions by the end of the decade.

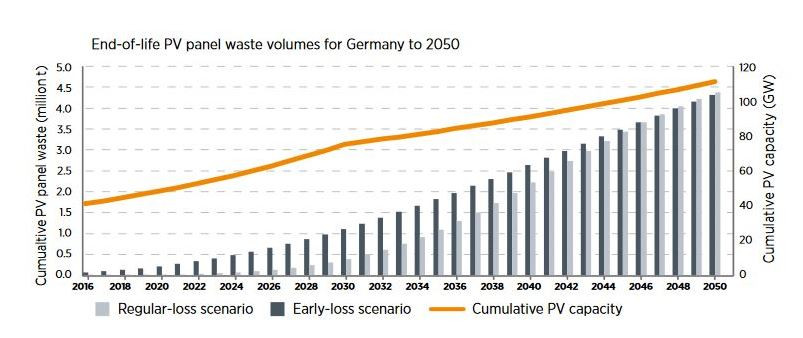

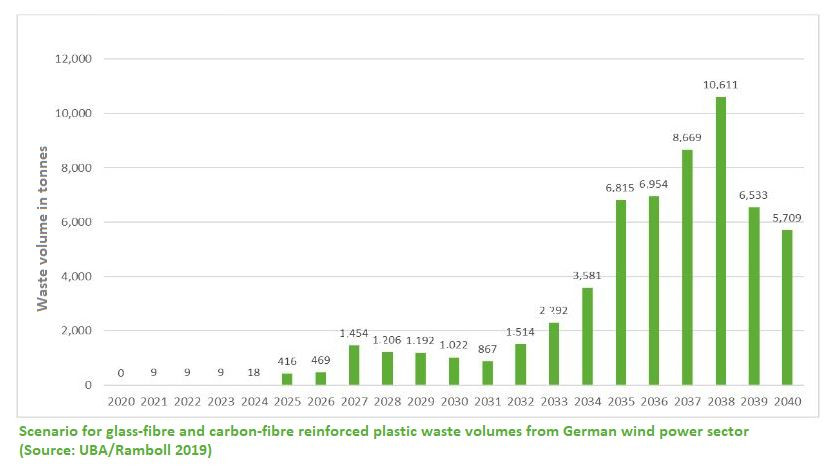

But with the volume of installed wind turbines and solar panels rising constantly and more and more e-cars getting on the road, a new question has started to loom large over energy transition: what to do once they drop out of the market? Green technology waste in the country has so far been largely limited to outdated or damaged installations at levels that appear minuscule compared to what lies ahead. In 2021, the first renewable power installations have started leaving the 20-year support scheme, meaning that thousands of large wind turbines and millions of solar power modules will be going out of service in the next years if no viable model to keep them running is found and, just like the batteries of millions of e-cars, will eventually end up as industrial waste.

This will require internationally accepted standards to ensure clean disposal of green technology goods, which in turn will make it imperative to find procedures to retrieve and recycle thousands of tonnes of valuable input materials like silver, copper, lithium or rare earth elements they contain. This is necessary to ensure that decarbonisation is done efficiently, and it also reduces reliance on resource imports for the energy transition, for which sufficient availability might become increasingly uncertain as Germany and Europe gear up for the aim of 2050 climate neutrality.

Waste offers treasure trove for climate plans

Policymakers across Europe will have to get serious about addressing this challenge soon, says Frank Kroll of wind turbine disposal company Neocomp in Bremen. "Several countries are facing the need to dismantle large quantities of renewables," with Germany being a relatively mature market that foreshadows what other countries that have commissioned large quantities of renewable power will be facing at some point too, Kroll told Clean Energy Wire. Kroll's company is one of only a few that have developed a procedure for returning shredded wind turbine blades into the economic cycle. The fibre-reinforced plastic blades are one of the most intricate energy transition wastes to treat properly and their mass disposal is feared to overstretch existing disposal capacities. Instead of burning the blade remnants, Neocomp reuses flakes of tricky composite materials, for the production of concrete, a major source of greenhouse gas emissions on its own. "Our approach is to reinject as much of the material as possible and technically reasonable back into the economic cycle," Kroll said. Reusing materials rather than burning them can improve each installation's ecological life cycle balance and also help save resources and emissions in concrete production, a further contribution to lower emissions.

But while the sustainable treatment of scrapped blades is a welcome solution to a growing and undesired side-effect of climate action measures, better recycling mechanisms for other energy transition materials could mean unlocking a real treasure trove. The stock of metal per capita in Germany is growing by almost 20 kilograms per year, even if the most widespread material -- steel -- is not included, calculations by the Öko-Institut have shown. In theory, a full recycling of the stock could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by about 634 million tonnes by 2050, the equivalent of four years of Germany's 2019 transport emissions, and could save the economy nearly 250 billion euros. A 2020 UN resource panel report found that the overall emissions reduction potential of material life cycle efficiency improvements would be in the range of 23 gigatonnes of CO2 by 2060 without a major impact on consumer comfort but with high savings potential also in the buildings and transport sectors.

Efficiency gains by recycling raw input materials rather than sourcing new ones can be enormous, improving the emission balance of metals like aluminium by up to 95 percent, according to recycling industry group BDE. The more often a resource unit is reused, the lower its energy consumption will be, leading to calls for including the metal recycling industry in the country's council on climate protection. While these "secondary resources" -- hidden in old turbine generators, batteries and solar panels, but also in discarded mobile phones, microwaves or TV sets -- could make a real impact on raw material import volumes, more primary resource from mining would still be needed due to the material needs of digitalisation and transitions in the energy and transport sectors, the Öko-Institute cautioned.

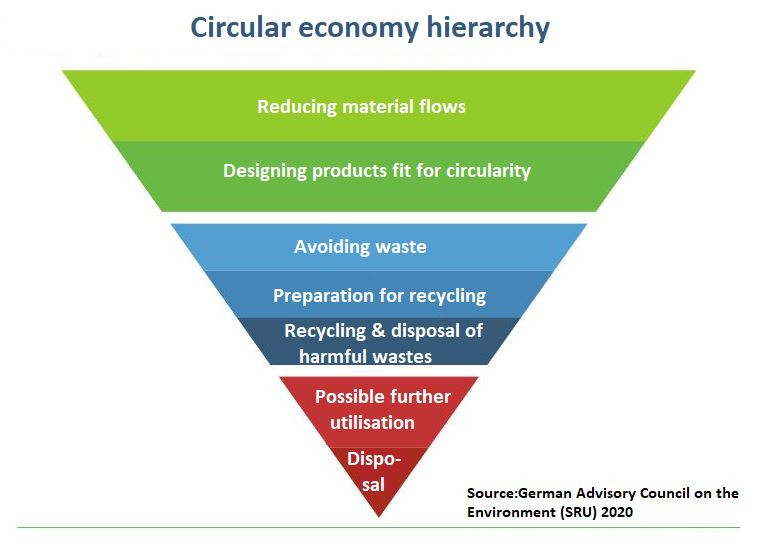

Current German and EU resource and recycling strategies fall short of embracing green technology

Even though Germany has no shortage of recycling systems, which exist for e-waste, batteries, plastics and even for solar power arrays, the government's environmental advisory council (SRU) in a 2020 report found that the country still uses way too many resources, consuming twice as much per capita as the worldwide average. But a clear national or European commitment to reduce material flows of low-carbon equipment or retain resources in the economic cycle in the first place so far remain lacking, the SRU said, calling for a more circular approach to input factors of production spanning the entire life cycle.

Renewable power installations and circularity concepts of the energy transition have so far " received inadequate attention only," Germany's environment agency UBA told Clean Energy Wire. The UBA said improving research across Europe on how to cope with and utilise the growing pile of energy transition leftovers will be necessary quickly, adding that expanding the running time of installations and also establishing second-life concepts for solar panels or batteries would be other options to reduce pressure on recycling mechanisms.

The German economy ministry (BMWi) has sought to address the so far underdeveloped role of recycling and "urban mining" for its renewable energy plans, making it one of the three pillars of its 2020 resource strategy. The ministry has vowed to reduce the squandering of valuable materials through research projects and foster dialogue in the industry that could also alleviate import reliance. According to the European Union's 2020 Circular Economy Action Plan, developing a truly circular economy would have to be "one of the main blocks" of the European Green Deal and a prerequisite for achieving climate-neutrality. But while the EU plan includes a chapter on e-car batteries – with its latest directive on this key mobility technology dating from 2006, when the currently dominant lithium-ion batteries weren't even widespread – it largely focuses on consumer waste like electronic devices and plastics.

For NGO PowerShift, Germany is punching below its weight in establishing better circularity standards for low-carbon technologies. "The country certainly is no frontrunner when it comes to supporting a more circular approach at the EU level," the NGO's resource expert Michael Reckordt said. The resource strategy would still come with a clear focus on securing access to primary resources. "It doesn't really make great strides in terms of supporting a circular economy approach," whereas ecological or social aspects only play minor roles and are not backed by any concrete measures, Reckordt argued. Much greater coercion and incentives for the production and recycling industries would be necessary to get things moving. Peter Kurth, head of the recycling industry association BDE, summarised his industry's discontent after the government's green stimulus package in the wake of the pandemic in mid-2020 was revealed to entirely bypass recycling: "They are spending 130 billion euros and are not even considering the potential of the recycling industry at all. This is more than disappointing."

Market could command its own cleanup

Getting a grip on managing energy transition waste does not have to involve more free-handed government support but rather devising recycling procedures that can compete economically with primary resource exploitation across the board. While establishing greater circularity will ultimately save resources and money, setting up a functioning system in the first place will be costly and require the intensive cooperation of actors along the entire production chain, including mining companies, manufacturers, retailers, consumers and disposal companies that have to rethink every step in the manufacturing process.

"The challenges here are very different depending on the product you look at," said Rainer Buchholz, head of recycling of metals industry group WVM. Batteries, electronic waste and scrapped vehicles would generate Germany's biggest domestic raw material supply. While the most valuable elements are often only used in small amounts in each discarded product, the sheer mass of waste can make meticulous segregation pay off. While casings for solar panels or batteries are relatively easy to recycle, the hard part starts with retrieving the elements within the actual cell or battery, where cost-efficient techniques are emerging but have yet to be rolled out at full scale. Half of all metals excluding iron, for example, are still discarded in Germany as they are difficult to collect, but metal parts would actually be the components most suitable for recycling in electronic waste, according to the WVM.

A functioning European market for recycled materials is needed to bring down costs and procedures to scale, Buchholz said, adding that the market benefit of recycled products could be observed in Germany's car industry, which has spent a lot of effort looking for ways to make combustion engines cleaner. Reducing the energy consumption would be almost impossible nowadays for a final product like a car engine, he said. "So, one option for making cars greener is to tackle energy consumption in production by using recycled materials." This has led to shortages of recycled products despite primary resources being available more cheaply, as carmakers are keen to pay higher prices for second-hand material. "A somewhat odd situation," Buchholz concluded.