New government gets little credit in quest to regain climate lead

Germany’s new government starts its work with only very limited credit in climate and energy policy. After a bumpy and very drawn-out government formation process, critics said the coalition treaty between Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the Social Democrats (SPD) lacks ambition and detailed measures to put the former climate action pioneer Germany back on track after its reputation suffered a severe blow during the previous term of “climate Chancellor” Merkel.

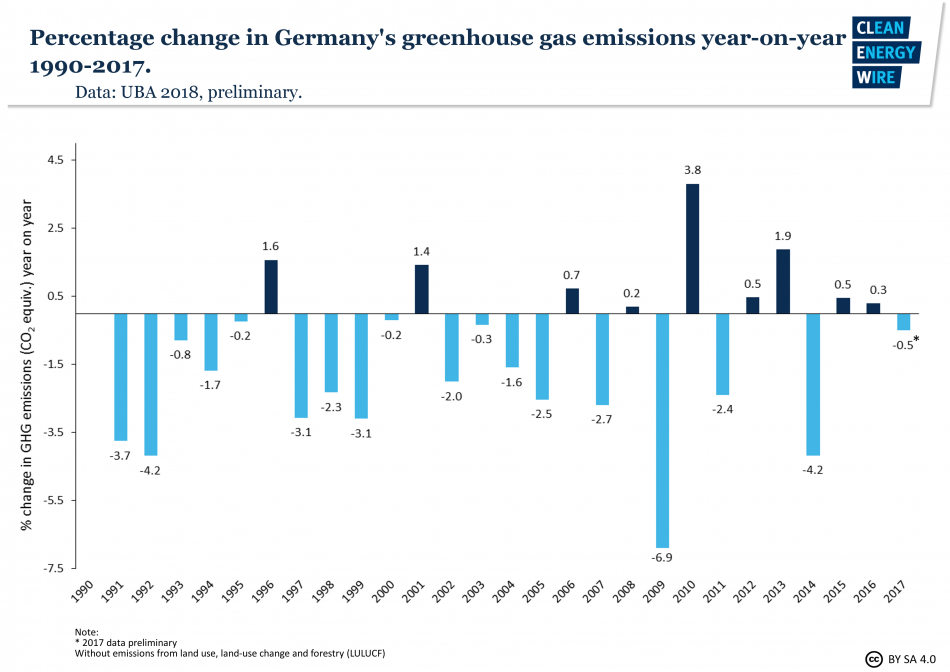

Germany is set to miss self-imposed and European emissions reduction goals while the distribution of costs of the Energiewende, the country’s dual shift from nuclear and fossil energy sources towards renewables, remains fiercely debated in Europe’s biggest economy.

Observers say the coalition treaty fails to clearly spell out how the country intends to curb emissions fast, increase energy efficiency, and boost the electrification of all sectors. But others say that there is hope in an ambitious goal to double down on renewable power production and the introduction of a Climate Protection Law that may put Germany firmly on track to meet future climate targets – if it contains the right policies and is rigorously implemented.

On the day of the new government’s swearing-in ceremony, the chancellor dryly said she is determined “to continue the Energiewende in a clean, secure and affordable manner.” Inexpensive renewable energy based on market-principles is decisive for Germany to reach international climate goals, Merkel said. But critics were quick to point out that Chancellor Angela Merkel dedicated a mere 40 seconds in her hour-long inaugural speech in parliament to the topic, saying this mirrored the lack of importance the coalition had assigned to climate and energy policy.

Prior to the elections that resulted in a renewal of the so-called grand coalition of Germany’s two biggest political camps the chancellor had already vowed to ensure that Germany would achieve its 2020 climate target – a promise that soon proved to be hollow as the target was effectively scrapped in the coalition treaty.

In Svenja Schulze’s first address to parliament, the new German environment minister seemed determined to rebuild Germany’s profile as a climate action forerunner. “Germany quickly has to restore its pioneering role” through a joint effort of the entire government and the country’s mighty industrial companies, Schulze said.

Germany “impressively disproves the thesis that economic success and ecologic sustainability are mutually exclusive,” she said, adding that she “will do everything to continue this success story.”Regardless of how the Energiewende’s previous success is evaluated, the challenges the world’s sixth largest emitter of greenhouse gases faces to continue it successfully are difficult and manifold.

Among the most controversial domestic debates are the end of coal-fired power production and emissions in the transport sector, including the looming diesel driving bans in many German cities, both of which the government wants to solve in external commissions to agree on a transformational path which reconciles emissions reduction with economic stability.

The intensifying debate over the distribution of the Energiewende’s costs and sluggish progress in improving the power grid infrastructure in a country that already sources over 36 percent of its power consumption from intermittent renewable energy sources add to the challenges for the new government’s climate and energy policy.

Social Democrat Schulze will mainly face two conservative counterparts in her bid to improve on Germany’s climate record, new economy and energy minister Peter Altmaier and new transport minister Andreas Scheuer. Both conservative ministers are bound by Germany’s internationally binding pledge to reduce emissions but environmentalists and energy transition supporters fear they might see their role primarily as advocates for the country’s industrial competitiveness.

In addition, the ministry for agriculture and the department for construction will be led by conservatives, adding an extra party political dimension to the environment minister’s already tough uphill struggle to improve the country's climate record.

Schulze’s Climate Protection Law to fill coalition treaty's blank spaces

Economist Andreas Löschel, head of the government-appointed independent expert commission on Energiewende monitoring, told the Clean Energy Wire that the coalition treaty’s provisions on climate and energy were “no ‘great breakthrough’ yet” but added that they “could become just that”. Löschel said the treaty demonstrated “a pretty clear commitment” to further expand renewable energy generation, increase energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions but lacked an outline of concrete steps and tools required to achieve the stated aims. “This now must be developed throughout the legislative period.”

In an analysis of the treaty, NGO Germanwatch said that except for the augmented goal of renewables expansion, from a 50 percent share of wind, solar and other renewable sources to 65 percent by 2030, the document remained remarkably vague. “This once more will cost precious time,” Germanwatch said.

Swiss consultancy Prognos, which regularly compiles studies for German policymaking, called the treaty “fragmented and incoherent”. It conceded that the agreement touched upon a wide range of relevant policy areas but was “marked by resounding silence” on topics such as the decarbonisation of industrial processes and energy efficiency.

However, Schulze’s most important tool for addressing the coalition treaty’s blank spaces on climate and achieving lower carbon emissions across the board will be a national Climate Protection Law, which she said would be introduced by 2019. It is meant to put flesh on the bones of the coalition treaty’s passages on emissions reduction and sketch detailed and binding measures for every sector concerned to ensure Germany reaches its 2030 climate target.

Schulze was science minister in the government in the country’s most populous federal state North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) that introduced Germany's first-ever Climate Protection Law in 2013. The NRW law’s aim is to provide a “legal foundation” for the planning, implementation and evaluation of measures that lead to a “lasting improvement” of climate action, but critics argue that it has failed to do so in the more than four years it has been in existence.

“The Climate Protection Law in NRW is arbitrary and non-binding. It has not delivered any substantial results,” Karsten Smid, climate policy expert at NGO Greenpeace, told the Clean Energy Wire. He said the law had neither abated coal mining activities in the state nor outlined a clear path for the region’s exit from carbon-intensive energy generation.

Smid said the new government must make sure that the national law planned for 2019 does not end up as toothless as its NRW counterpart. The basic framework on sectoral emissions reduction that the law ought to cover is already outlined in Germany’s Climate Action Plan 2050, he argued.

“But the new law must make the plan legally binding and perhaps even tighten it as it had been decided before the Paris Agreement,” Smid said. Germany currently is not only at risk to miss its national 2020 climate target, but also a target by the EU for sectors that are not covered by the union's emissions trading scheme (ETS), such as transport or agriculture. These too would have to be addressed in the climate law.

The Federation of German Industries (BDI), Germany’s most important industry lobby group, is also wary of the proposed law as it might impede on the companies’ flexibility. “Climate protection and economic development should be seen as equally important goals,” Joachim Hein, climate and energy policy consultant at the BDI, told the Clean Energy Wire.

A climate law should not only fix emissions reduction goals but also include economic indicators, such as employment perspectives and economic growth, the organisation argues. The BDI recently published a study saying that climate action overall would benefit the German economy.

“Just like we’ve determined indicators for climate action, we need indicators for competitiveness and we need to monitor them,” Hein said. He warned that merely fixing the number of tonnes of CO2 that have to be cut by 2050 would spell difficulties for the German industry. “But if the law means that we get increased monitoring that allows us to change course if necessary, it would indeed be reasonable for us,” Hein said.

Coal commission aimed at pacifying a central climate-policy battleground

The planned commission on “growth, structural economic change and employment” – the coal commission – is meant to deliver exactly this synthesis of rigorous climate action and careful industrial policy, according to the coalition treaty. It is supposed to bring policymakers, industry representatives, environmental NGOs and labour unions to the table to decide on a roadmap and a clear end date for coal-fired power production, Germany’s single-largest source of carbon emissions.

The first touchstone for the new government’s efficacy in reconciling emissions reduction with economic stability is supposed to deliver results, including an end date for coal, in 2018. Several German NGOs made clear that their participation will hinge on prerequisites to ensure tangible results, including a “clear exit path” for coal and an intermediary 2025 climate target to assess progress made towards the binding 2030 target.

IG BCE, Germany’s biggest energy and mining labour union, on the other hand, argues that the country’s market forces will inevitably phase out hard coal and lignite sometime in the 2040s. Union leader Michael Vassiliadis, who is likely to play a central role in the commission’s deliberations, said setting end dates and stage goals was merely playing “number games”. “I’m tired of talking about the exit date for coal in excruciating detail – and remaining very vague and superficial on the aftermath,” Vassiliadis told the Sächsische Zeitung.

Felix Matthes of the Institute for Applied Ecology (Öko-Insitut) said the commission’s schedule was “completely unrealistic” anyway. Once the task force has finished its work and is able to present viable legislative initiatives, the parties will already be in election mode again, Matthes said.

His assessment of the commission’s inherent difficulties is underpinned by a struggle between the economy ministry and the environment ministry over who will be in charge. While environment minister Schulze argued that both administrations are equally concerned, economy minister Altmaier said it would “make sense” if his ministry is in the driver’s seat.

Costs and integration of renewables central challenges for Altmaier

Altmaier’s claim for leadership of the coal commission resonates with his assertive approach in other central Energiewende issues, namely the debate over costs and the integration of wind, solar and other renewable sources in the German power grid. The former environment minister long styled himself a mediator between business-friendly and environmentalist views.

But in one of the first remarks in his new role as economy and energy minister, he left little room for doubt that he will adopt a business-friendly attitude in his upcoming term. His ministry would primarily be “a ministry for small and medium sized companies,” Altmaier said and promised German companies that they would not face competitive disadvantages over their European competitors.

The distribution of Energiewende costs and the system of surcharges and levies indeed is a pressing concern for many stakeholders in Germany. The government’s advisory board on environmental policy, which is largely unsuspicious of pro-industry bias, as well as industry associations such as the BDI, the German Chemicals Industry Association (VCI) and the German Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW) say the country’s energy surcharge and levy system needs an overhaul.

Yet their propositions on what this reform should look like are likely to differ. While industry representatives are insisting on lowering costs for power and for Germany’s renewables support scheme (EEG), environmental groups are advocating for a reorganisation that focusses on pushing carbon-intensive energy sources out of the market.

A central argument will be the carbon floor price in several European countries proposed by French President Emmanuel Macron. In the coalition treaty, the parties vowed “close cooperation” with France in implementing the Paris Climate Agreement and the commitments made at the 2017 One Planet Summit – a promise that makes it hard to simply rebuff Macron’s proposal.

But sources close to the coalition negotiations told the Clean Energy Wire that no such policy has a chance of being discussed further before October, when the next election in Bavaria, Germany’s southern economic powerhouse and home state of the regional conservative party CSU, will take place. “They don’t want to deal with greater costs for commuters or for heating before the election,” the person said.

Apart from revamping the Energiewende’s cost structure, grid expansion has been called a “top priority” by Altmaier. The construction of major transmission lines across the country is encountering opposition by residents and local lawmakers alike while the EU and industry groups urge the government to speed up construction to safeguard a stable power supply from intermittent renewable power sources in Germany and beyond. The country’s aim to phase out nuclear power entirely by 2022, one year after the new government’s regular term ends, is adding further pressure for the transmissions lines’ completion.

Altmaier promised that “after six months in office, I will know every problematic line personally and will have visited it,” but the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) already warned that a ramped-up renewables goal could render current grid expansion plans obsolete. BNetzA head Jochen Homann says reaching a renewables share of 65 percent by 2030 is not only “ambitious,” but would also overstrain the grid. Homann says the parties were “smart” to include a caveat in the treaty that the country’s grid must be able to manage additional power flows before more renewables can be integrated.

Transport minister Scheuer between “clean air” and “hot air”

Another field that will require immediate action by the new government is transport. In particular, this concerns Germany’s powerful automotive industry, which is still embroiled in the diesel scandal over manipulated engines. Not only does the country face driving bans for diesel cars in inner cities due to high levels of air pollution, the EU also has threatened to sue if it does not find quick solutions to bring pollution in line with European limit values.

To make matters worse, the transport sector has increased its CO2 emissions in recent years rather than reducing them, thereby contributing a great deal to the country’s failure to meet its 2020 climate target. Schulze’s declared goal to re-establish Germany as a forerunner in climate action therefore also greatly depends on new transport minister Andreas Scheuer.

Scheuer’s task will be to manage the double challenge of reducing emissions and finding a solution to the diesel crisis, with its ramifications on air quality, the involved companies’ stability and affected diesel car owners. Chancellor Merkel has stressed that the diesel crisis would be among her administration’s highest priorities but at the same time admitted that solving the situation was tantamount to “squaring the circle”.

However, Scheuer's first statements do not suggest that the country’s mighty car industry has to suddenly brace for a tougher handling than under his much-criticised predecessor Alexander Dobrindt. Scheuer has stated that he wants to “energetically continue” his predecessor’s policies and even “make clean air an export hit” for Germany – stopping short of explaining how this will come about. He was instantly criticised on social media by environmentalists as “minister for hot air.”

In his inaugural speech, Scheuer reassured parliament his motto was “no panic, no bans”, and that the government was on track to speedily implement the measures agreed at last year’s diesel summits. However, sustainable transport association VCD said Scheuer’s maiden speech was “a bitter disappointment”. VCD head Wassilis von Rauch argued: “We need a U-turn instead of preserving the status quo.”

Difficult political starting conditions could push climate action aside

Aside from the range of challenges that Germany’s new government needs to overcome in energy, transport and climate policy, the significant transformation the country’s political landscape has undergone in the last legislative period is likely to weigh heavily on policy priorities.

The right-wing nationalist party AfD became Germany’s third biggest political force with an election campaign that focussed on criticising the intake of hundreds of thousands of refugees and asylum seekers and a more broad attack on the country’s political and economic “elite”. It has also occupied a previously vacant role in the German parliament by becoming the first party to openly question the existence of man-made climate change and actively seize the anti-energy transition mood in some parts of the population.

News magazine Der Spiegel argues that the AfD’s success, paired with the coalition parties’ losses at the ballot in September, has shifted the political focus and made climate and environment concerns a “niche topic” for the new government. Merkel’s fourth and probably last term as chancellor will prove whether the magazine is right or Germany can pick itself up to become a pioneer in climate action again.