Energy sector drives slight drop in German emissions in 2017

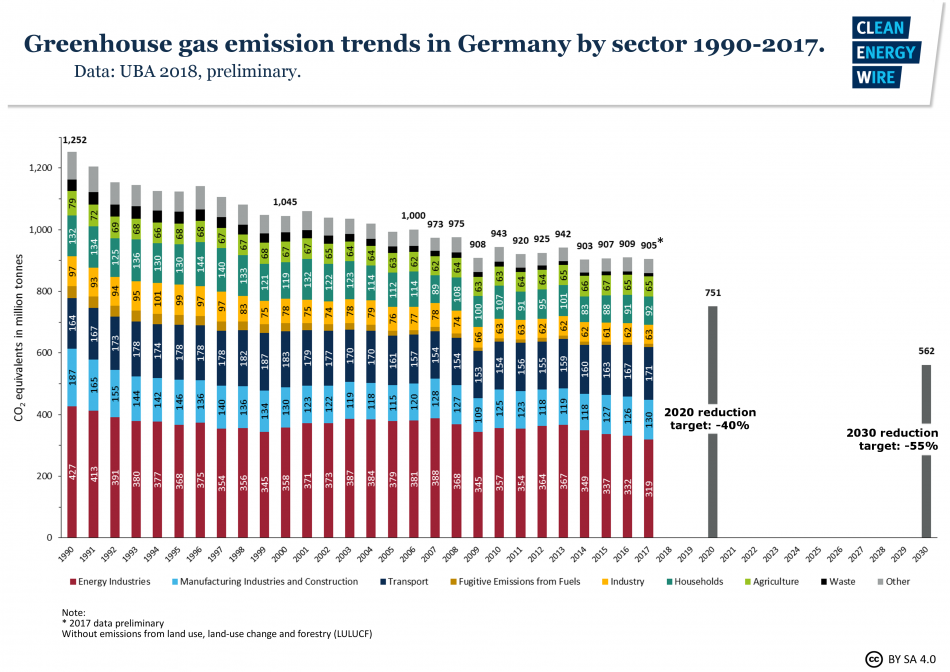

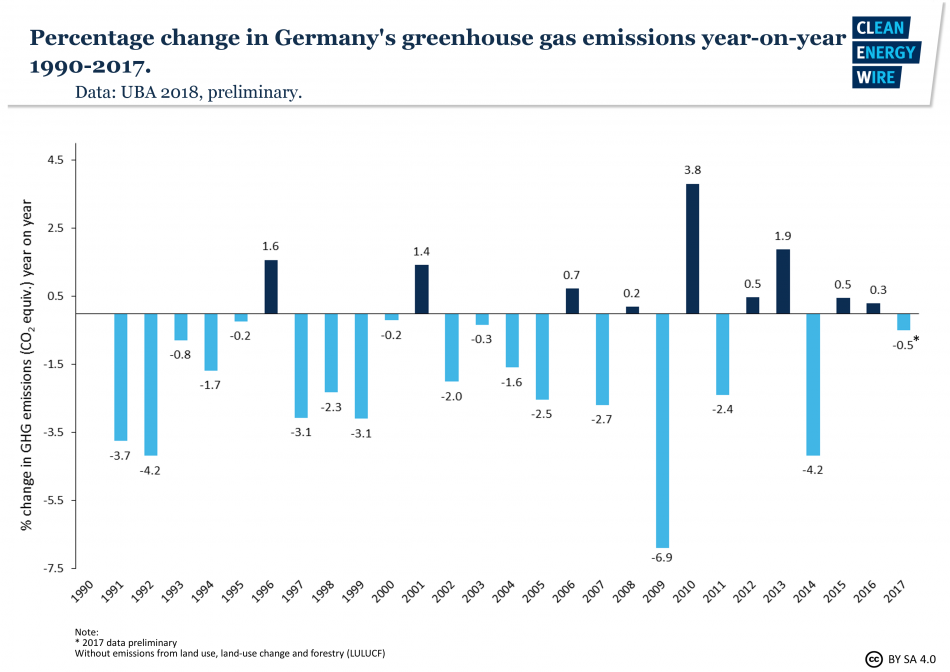

In 2017, the large wind power feed-in pushed down hard coal use for power production and helped Germany reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by a total of 4.7 million tonnes CO₂ equivalent, or 0.5 percent, according to the Federal Environment Agency’s (UBA) latest estimate. Compared to 1990, Germany’s emissions were down 27.7 percent at 904.7 million tonnes last year.

Hard coal emissions were down 13 percent compared to 2016, also due to 3 gigawatt capacity shut down or put into a reserve in 2017, while emissions from lignite were down slightly by 0.6 percent. Emissions from mineral oil – by far Germany’s single largest source of CO₂ emissions – were up 2 percent. Emissions from natural gas production rose by almost 5 percent in 2017. UBA points out that its data are based on a first estimate, which it adds is more uncertain than in previous years.

Having failed on its own emission reduction pledges, Germany’s new federal government is now under pressure to act on emissions and reclaim the country’s role as a worldwide pioneer in climate action. Earlier projections had forecast a slight increase in the country’s energy-related CO₂ emissions for 2017. Germany aims to reduce total greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2020, a goal likely to be missed by a wide margin.

The data shows that additional measures are needed to put Germany back on track to reach its climate targets, write UBA and the Federal Environment Ministry (BMU) in a joint press release. The energy industry is responsible for about one third of Germany’s total greenhouse gas emissions. According to UBA data, apart from waste disposal, this was the only sector that managed to reduce emissions in 2017. The booming economy had pushed industrial emissions up by 2.5 percent, while agricultural emissions stagnated.

Transport sector heading in the wrong direction

In their joint press release, UBA and BMU singled out the lack of progress in the transport sector. The increasing number of vehicles on the road and the booming freight transport caused emissions to rise by 2.3 percent in the sector.

“In the transport sector, the developments unfortunately are still moving in the wrong direction,” said the new environment minister, Svenja Schulze. “We need a fundamental transition in the transport sector toward climate protection and clean air. This must become a focus of this legislative period.”

Until now, carmakers have tended to stress that diesel is the most efficient technology available, has a smaller climate footprint than petrol-based technology, and is needed to enable the country to reach its climate targets. However, the decreasing share of newly registered diesel cars and the increasing share of petrol cars contributed little to the rise in emissions, said UBA President Maria Krautzberger.

“It’s wrong that we can only reach our climate targets with the help of the diesel. We need less and much more efficient vehicles in general, no matter how they are fuelled,” Krautzberger said. The EU’s proposals on fleet-wide average CO2 emissions currently on the table are not sufficient, and the 2030 transport sector targets will be missed without further action, said Krautzberger.

Environmental NGOs want more action on lignite

Environmentalists picked up on the news of stagnating emissions from lignite. Karsten Smid, climate expert at Greenpeace Germany, called for action to phase out “the most climate-harmful way of power generation.” Only hard coal power production had been decreased because of the strong wind feed-in, said Smid, and added that the 2020 climate target could only be reached if also lignite power plants are “shut down and throttled on a large scale”.

The new government has agreed in its coalition treaty to introduce a multi-stakeholder commission – the so-called coal commission – to work out a plan for the phase-out of coal-fired power production and set an end date by the end of 2018. According to news agency dpa, several German environmental organisations say they want to have a range of assurances from the German government before they participate, including a “balanced representation” of interest groups in the commission, “a clear exit path” for coal, and a 2025 climate target.

Stefan Kapferer, head of the German Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW), sees the responsibility for emissions reduction chiefly in other sectors. The UBA data showed that the energy industry “is doing its share to protect the climate”, while transport is the main problem, said Kapferer in a statement. Now, CO₂ emissions in transport, agriculture and heating needed a price tag to help bring down emissions in these sectors.