New German environment minister faces steep uphill battle on climate

Restoring Germany’s tarnished reputation as a climate champion; pushing for an exit from coal-fired power generation; building bridges between winners and losers of the Energiewende; and driving the broader environmental protection agenda – the country’s new environment minister, Svenja Schulze, will have little time to get accustomed to the pressures of the federal political arena.

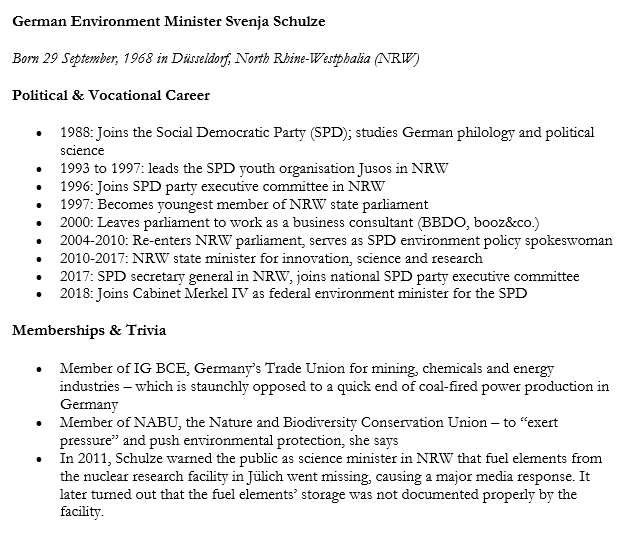

Schulze, a 49-year-old Social Democrat, hails from the industrial heartland of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW). A member of the staunchly pro-coal IG BCE mining workers union and the climate-conscious environmental organisation NABU, she now moves from Düsseldorf, the capital of NRW, to Berlin to become Germany’s highest climate policy official at a time when the former climate pioneer is failing on its greenhouse gas emission pledges, and the roll-out of renewables and the extension of power grids are meeting local resistance.

Nearly six months after Germany’s general elections in September 2017, Chancellor Angela Merkel has finally started her fourth term heading a coalition of her conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the Social Democrats (SPD), who have been reluctant to enter the government again as they fear losing their political profile in another partnership with Merkel.

The losses suffered by the grand coalition at the ballot forced the parties to find fresh faces, triggering Schulze’s sudden career boost. She replaces fellow NRW Social Democrat Barbara Hendricks, who overcame initial scepticism and earned the respect of climate activists for her unrelenting efforts to secure a global climate agreement in Paris.

Schulze has been little known outside her home region, Germany’s largest federal state, where she had become secretary general of the SPD’s largest regional association after the party lost the 2017 state elections. Schulze, who was part of the negotiating team for the federal coalition agreement, will have to help broker a compromise on the country’s coal exit in the planned coal commission, and is under pressure to come up with first results already at this year’s COP24 UN climate conference in Poland.

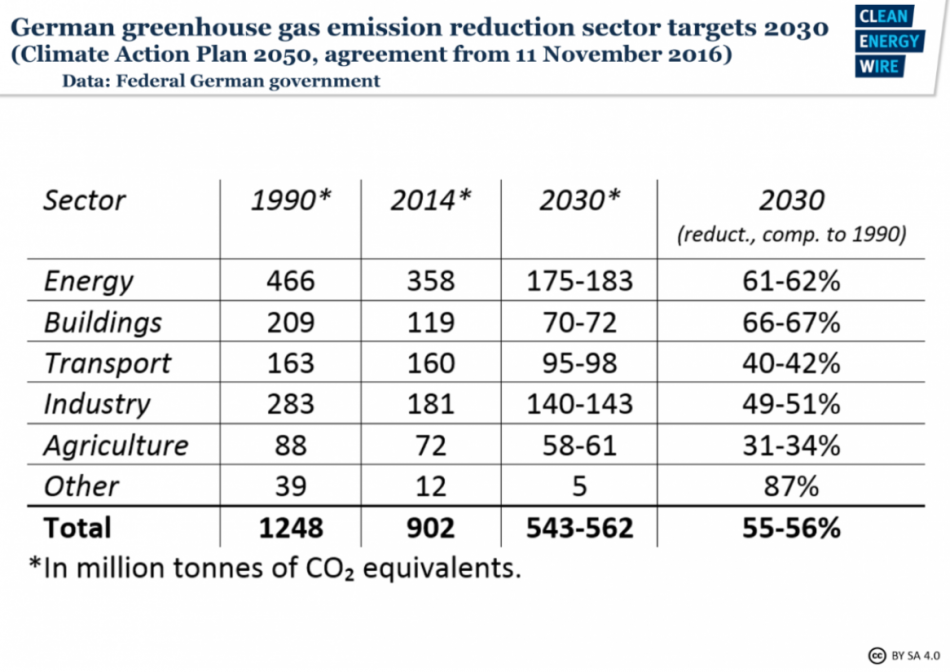

Moreover, she has to face up to Germany’s mighty car industry and appease the European Commission as a number of cities may impose driving bans to tackle air pollution from diesel cars. She will also have to push for clear pathways to meet the controversial sectoral emissions reduction goals laid out in the Climate Action Plan 2050, all to be enshrined in the climate protection law the new government has promised.

The former state science minister will have to push her agenda in negotiations with a number of conservative political heavyweights. Her main counterpart will be economy and energy minister Peter Altmaier, a long-time Merkel confidant. But the other newcomers, such as transport minister Andreas Scheuer, former secretary general of the Bavarian conservative party CSU, and agriculture minister Julia Klöckner, one of the CDU’s vice-presidents, will also be keen to prove themselves.

Schulze’s job as federal minister for the environment and nuclear safety has become harder as her ministry has been stripped of levers to directly influence climate relevant areas. After renewable energy policy had been removed from the ministry’s portfolio during the previous legislative period, it now also loses construction and building policy, which includes regulation on key energy transition areas such as efficiency, to the newly expanded interior ministry under CSU chairman Horst Seehofer.

In addition, Schulze’s party has been left deeply unsettled by its election loss, and is reluctant to alienate voters in traditional industrial regions, which the SPD still considers its heartland.

Reconcile coal workers’ interests and climate

Media commentators have been quick to pick up on her dual membership in both the environmental organisation NABU – for which a quick coal exit is key to fulfilling Germany’s climate obligations under the Paris Agreement – and the trade union for mining, chemicals and energy industries (IG BCE) – a staunch opponent of a speedy coal exit.

SPD chairman Olaf Scholz, the new vice-chancellor and finance minister, said at the presentation of his party’s cabinet members that Schulze, a trained German philologist and political scientist, “has always fought for the climate and the environment with her whole heart,” and will be “an excellent minister.” She earned expertise in the field as the SPD’s environmental policy spokeswoman in NRW before she was appointed state science minister in 2010.

Schulze herself once said she joined the IG BCE “because I think it’s important to get along on a fair and just basis in society,” an aim that made solid lobbying for the interests of workers necessary.

But Tobias Münchmeyer of Greenpeace Germany voiced doubts. The minister has to “quickly prove that she’s independent when it comes to the central question of a coal exit,” he said. Schulze could only meet the high expectations attached to her office “if she’s ready to fight with the other ministries” and to advocate a quick shut-down of Germany’s oldest coal plants, Münchmeyer said.

People who have worked with her in NRW have little doubt about her commitment. “She is authentic and definitely has a big heart for the environment,” Josef Tumbrinck, head of NABU in NRW, told the Clean Energy Wire. Schulze would have loved to become environment minister in her state. “But in a coalition with the Green Party, there was no chance for the SPD to get this office,” Tumbrinck said.

Big test: coal commission

Her first major test could be the coal commission, the grand coalition’s answer to one of the most divisive issues in Germany’s climate and energy policy. The CDU/CSU and the SPD have agreed on setting up a commission under the lead of Altmaier’s economy ministry. It will discuss the requirements and ramifications of a coal exit in Germany by bringing together political actors from affected federal states, representatives of labour unions, industries and municipalities, as well as environmental groups. The coalition parties have vowed to present a clear roadmap, including a target date for the exit, before the end of 2018 - a very tight deadline even under the best of circumstances.

Schulze will also be in charge of overseeing Germany’s planned nuclear exit, which is scheduled to be finished by 2022, the year after her term regularly ends in late 2021.

On climate issues, she can count on current State Secretary and fellow Social Democrat from NRW Jochen Flasbarth, who was a leading member of Germany’s climate policy negotiating team at international meetings in recent years. The former head of the Federal Environment Agency UBA had already announced his departure, but now decided to stay on.

Schulze herself has shown the sort of determination needed to overcome challenges in the past, people who have worked with her told the Clean Energy Wire. During her tenure as science minister in NRW between 2010 and 2017, Schulze repealed the academic tuition fees introduced by the previous government coalition of the CDU and the pro-business FDP, making good on a central election promise of her party. Her far-reaching reform was met with strong resistance as it curtailed the power of university councils and placed them under her ministry’s scrutiny, which earned her the anger of university rectors but also the respect of others for her stamina.

Schulze has climbed the SPD’s internal career ladder without apparent setbacks since joining in 1988. After heading the student union at her alma mater in Bochum, and subsequently the SPD’s youth organisation Jusos, she became the youngest member of NRW’s parliament in 1997.

Schulze said she “consciously” dropped out of politics in 2000 “to build up a professional career” by joining a business consultancy in Hamburg. She later moved on to the US company Booz Allen Hamilton, known for its close ties to the American intelligence services, where she “advised municipalities and insurance companies in Germany and beyond.” She re-entered the state legislature in 2003.

During her time as NRW’s science minister, Schulze created a stir when she stated, in response to questions in parliament, that over 2,000 nuclear fuel elements had gone missing from a research facility at Jülich near Cologne. Explaining that the nuclear waste had “probably” been disposed of illegally in the Asse underground mine, she issued a warning to the public and ordered a special meeting of Jülich’s advisory board.

NRW’s nuclear regulation authority quickly clarified that, in fact, no fuel elements were missing. A commission of inquiry later found that the research facility had failed to properly document its nuclear waste treatment processes. Schulze weathered the affair without any grave consequences.

According to the left-wing German newspaper taz, Schulze’s evolution from a young Social Democrat leader to a career consultant has “slowly moved her from the left fringes to the political centre.” The new minister herself said this experience helped her “to get to know companies and administrations from the inside and from the outside” – a skill that she said comes in handy “to help create new jobs.”

NABU’s Tumbrinck, agreed that Schulze’s experience in the business world, as well as her IG BCE membership, could ultimately turn out to be an asset. “She wants to build bridges between the industry and environmental protection,” he told the Clean Energy Wire. “Hers is not a confrontational approach. She wants to convince people. Whether this will work is an entirely different question.”

On her own website, under the title “Strong economy – active climate and environmental protection,” Schulze offers an elaborate explanation of how she aims to “reconcile” resource-consuming growth and job creation with a sustainable management of the ecosystem in NRW and beyond. The term “coal exit” is remarkably absent.