New German govt enters 2022 with no time to lose in race for climate neutrality

The year 2022 marks a fresh start in German politics as a new government has replaced long-term leader Angela Merkel after 16 years and starts off into its first full year in power. The three-party coalition led by Social Democrat (SPD) chancellor Olaf Scholz has repeatedly stated that improving Germany’s climate policy and bringing it in line with the Paris Climate Agreement will be among its most important tasks.

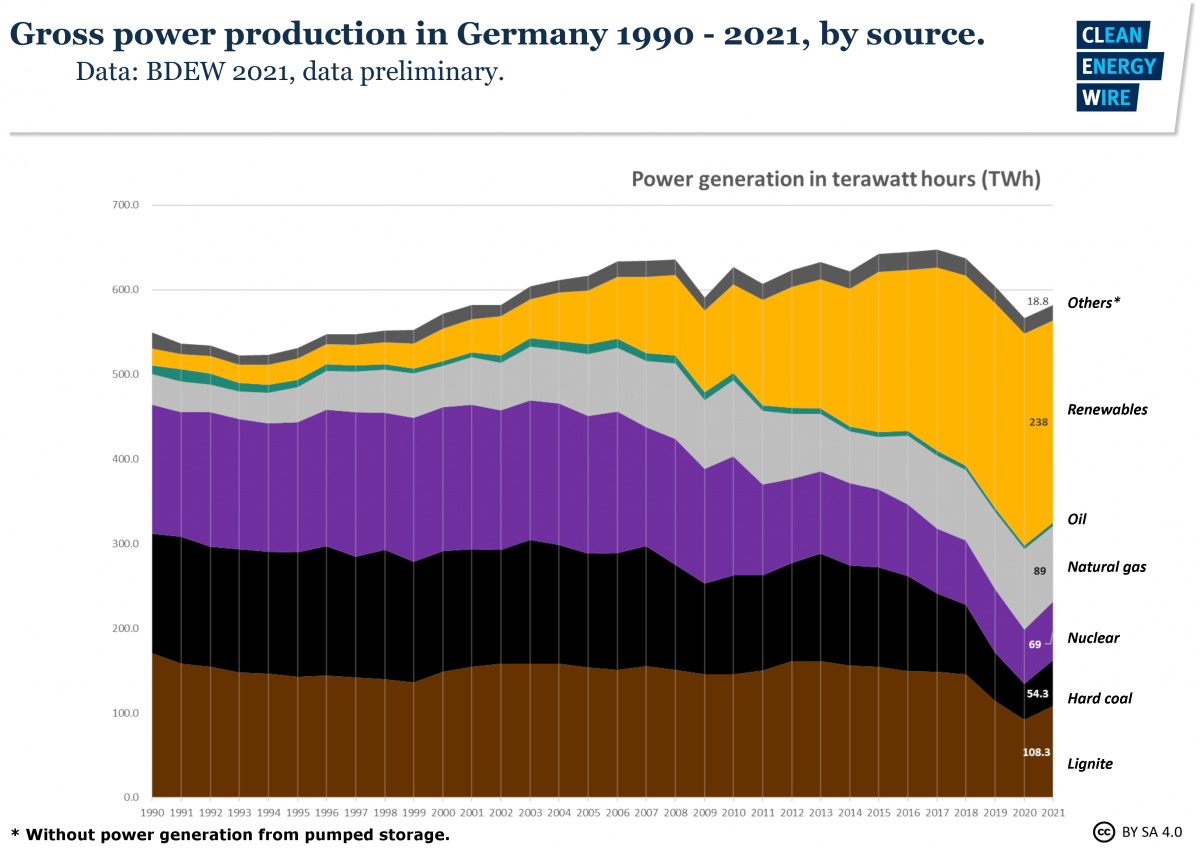

This means the “traffic light coalition” -- named after the colours of the SPD, the Green Party and the Free Democrats (FDP) -- will need to prepare the ground in 2022 for its ambitious overhaul of the German economy and energy system and reaching the goals for emissions reduction and renewable power expansion by 2030. But rising energy consumption and falling renewables output in 2021 suggest they will need to enact change quickly to get there.

After the election, the new government impressed observers with a swift and quiet transition of power that led to a new coalition treaty and Scholz’s inauguration in early December. The traffic light parties have taken over at a time when the coronavirus pandemic again flares up across Europe due to the novel Omicron variant, meaning the new government’s first weeks in office are likely to be dominated by pandemic response measures. But if the parties want to make good on their promise to initiate a true booster in German climate action, they cannot afford to put preparations for it on the backburner.

“What is needed is less politicking and more actual course-setting,” said Veronika Grimm, a member of Germany's council of economic experts, one of the country's most important advisory committees. Fast action would be needed to lay the groundwork for changes that are taking effect in the coming years, Grimm said, with the aim to make climate-friendly business models more attractive than those based on fossil fuels. “This will not be achieved overnight, but it must happen quickly."

Fast implementation of 2022 action programme only a first step

The first 100 days in office are a commonly used marker in German media for giving an early assessment of a newly elected government’s performance. For the traffic light coalition, this threshold will be reached on 17 March. While it is unlikely that many policies initiated by the new cabinet or individual ministers will already have taken full effect by that date, the new government’s start phase nevertheless offers important insights into potential conflicts that could hobble policy plans later on.

The new government has inherited an “Immediacte Climate Action Programme” for 2022 from its predecessor. It allocates an additional eight billion euros to emission reduction projects, with most of the money going into building modernization and hydrogen-based industry decarbonisation. Both the renewable energy lobby group BEE and the country’s largest power producer RWE have urged the traffic light coalition to forcefully enact the action programme and also draft a clear framework for the time until 2030 as soon as possible in the new year.

As a first step to prepare investments in cleaner infrastructure, Scholz’ cabinet passed a supplementary budget in late December to boost the country’s climate and transformation fund with debt-financed 60 billion euros. The move has been criticized by auditors and could also be a target for attacks by the conservative CDU/CSU alliance. The CDU will elect right-winger Friedrich Merz as leader of the opposition in January, suggesting that debates over the general course of the country’s climate policy could become more heated in the next year. The new government also already said it will extend the e-car buyer’s premium to 2022, adding it will be amended in the following year to only apply to electric vehicles with a proven positive effect for the climate.

Moreover, the country is going to shutter half of its remaining nuclear power capacity at the end of 2021 and is determined to phase-out the energy source completely by the end of the following year. But if unusually cold periods in January and February are going to exacerbate already skyrocketing gas prices, as market observers have warned, the traffic light coalition could quickly find itself in a brawl over the timing and general desirability of the long-planned departure from the technology. And the ongoing uncertainty over the role of the controversial natural gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 in the developing crisis on the Russian-Ukrainian border holds further risks regarding Germany's secure energy supply already in the first months of the new year.

“The chancellor's office must play a decisive role”

Apart from monitoring public opinion about its own debut in office, the coalition is likely to also keep an eye on a string of state elections next year, including the biggest planned event in German politics in 2022, the state election in the most populous state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) on 15 May. The SPD hopes to score yet another victory over the conservative CDU and snatch the highly industrialised state away from incumbent premier Hendrik Wüst, fully aware that the government parties’ performance at the federal level will influence voter decisions also at the state level.

Beyond handling domestic politics, huge tasks for the new government regarding climate and energy also await in European policy and beyond, government advisor Grimm said. In the EU, a quick and “decisive effort” by Germany for emissions trading in the EU would be needed. In other international settings, for example during its G7 presidency starting in January 2022, the government ought to push ahead with the idea of an international “climate club” to harmonise and coordinate climate policies. For the government advisor, the decisive question in this regard is not whether individual ministers are making fast progress in reducing emissions in their own sectors but rather how well the different branches of government interlock to form more coherent framework conditions conducive to climate action.

“The chancellor's office must play a decisive role here,” she argued. Of course, ministries traditionally linked to climate, such as those for transport, agriculture, buildings, environment and research, all would need to come up with a viable strategy for how they plan to contribute to the emissions reduction plans. But also, ministries that have so far had little overlap with climate policy, such as the treasury, the foreign ministry or that for development cooperation, would now be needed to orchestrate a coherent government approach. “Climate protection is a global challenge,” she stressed.

"Massive" renewables push is government's most urgent climate policy task

Even though many ministries play an part in the traffic light coalition’s climate plans, the early days of new economy and climate minister Robert Habeck from the Green Party will arguably be the ministerial kick-off watched most closely by climate and energy policy observers. After separating most of the government’s climate department from the environment ministry and integrating in a “super ministry” together with economic affairs, Habeck has said he considers reconciling emissions reduction with economic growth his most important task in the next years. Critics have called the reshuffling of competencies a move that could backfire due to the economy ministry’s inbuilt focus on prosperity rather than sustainability.

Getting renewables growth on track towards reaching the very ambitious goal of an 80 percent share in power consumption by 2030 will arguably be one of the hardest tasks the new government is facing. The traffic light coalition has increased an already ambitious target of increasing the renewables share in Germany’s power mix to 80 percent by 2030 -- roughly a doubling of capacity within the next eight years. Alas, the latest data on power production indicated that the share of renewables in the power system has actually been shrinking in 2021 for several reasons, including slow capacity expansion and little wind. Emissions, on the other hand, appear to have risen significantly due to economic recovery and cold weather.

Habeck said that the required boost to the national renewables capacity – which needs to grow up to four times faster than it currently does – will lead to intense debates in society, explaining that there are a number of short-term measures he intends to take to lay the groundwork for faster expansion during his first months in office. This includes an “opening balance” at the beginning of the year that details the state of energy transition and climate protection measures and giving renewables priority in adequate areas where construction is currently blocked.

But the real work would consist in preparing an even bigger overhaul of the regulatory and financial framework, an endeavour whose effects would only become visible in the years to follow. Other closely related measures that need to be initiated without delay in order to stick to the timetable include preparing the phase-out of Germany’s renewables levy, advancing grid expansion and creating secure planning conditions for green hydrogen production.

For Rainer Baake, former state secretary in the environment ministry and now head of NGO Stiftung Klimaneutralität, there is no such thing as “the one crucial task” for the new government to prepare for the needed transition turbocharge. “We need an immediate action programme that encompasses all sectors,” Baake said. If anything, a faster coal exit would be key to ensuring that the energy sector makes the requisite contribution to emissions reduction by the end of the decade. And this would require a “massive” push in renewables expansion. “If the additional electric power that we need for e-cars, heat pumps and hydrogen comes from coal or natural gas plants, we will merely shift emissions and miss the climate targets.”