Merkel leaves work to do with mixed climate legacy

- On her way out, chancellor Angela Merkel defends her reputation as “climate chancellor” – “I have devoted a great deal of energy to climate action.”

- Critics say her government nearly wasted a decade on domestic efforts, but give her credit for closing the ranks and ensuring compromise at EU and international level.

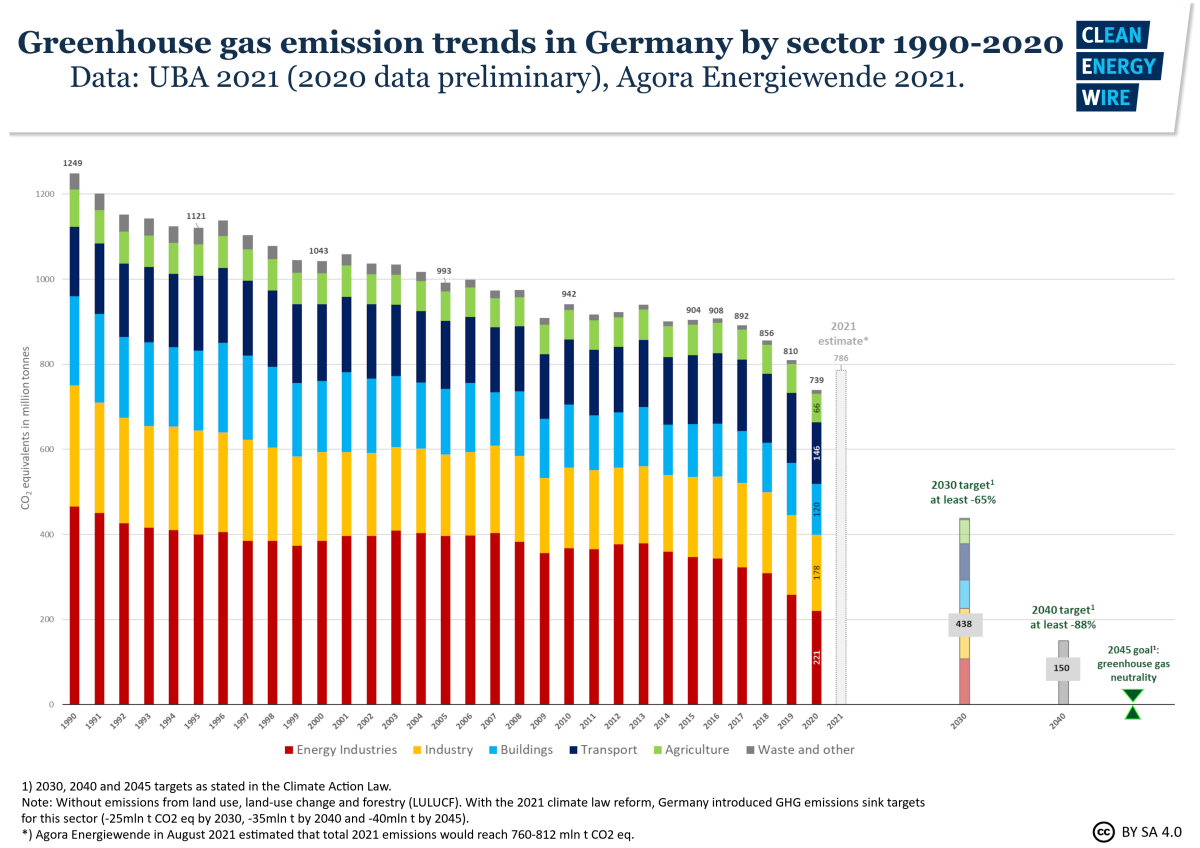

- As Merkel’s last year in office draws to a close, her legacy may now be tainted by a strong rebound of emissions after the coronavirus crisis. Instead of presenting a perfect image of Merkel’s goal of a green recovery, the rise would throw the country off course to meet its 2030 target.

- Her approach that there is no progress without compromise “distinguishes her from other politicians who tend to think in terms of victory and defeat,” says journalist and “Chancellor-Watcher” Andreas Rinke.

- Merkel’s style is "leading from behind” with an extraordinary sense of opportunity, says government advisor Ottmar Edenhofer.

- The ‘auto industry chancellor’ has also prevented progressive decisions. “When really big German interests were at stake it was a tough power game,” says former European Commissioner Connie Hedegaard.

- In the end, Merkel’s climate legacy will be decided by the success of her successors. First tests include the G7 presidency and the EU’s ‘Fit for 55 package’ of energy and climate legislation.

“I have devoted a great deal of energy to climate action [...] Nevertheless, I am sufficiently equipped with a scientific mind to see that the objective realities show that we cannot continue at this pace, but that they require us to speed up.”

Those were the words of German Chancellor Angela Merkel – a physicist by training – at her last annual press conference, just days after catastrophic floods killed more than 200 people in Germany and neighbouring countries in July 2021. As reporters flung questions at her, Germany’s 16-year leader strongly defended her embattled reputation as “climate chancellor”. “I believe that I have used a considerable amount of strength and also a high degree of continuity” to protect the climate, she said.

But ahead of the German election on 26 September, critics disagree. Europe’s most powerful leader faces a mass movement of climate protesters, led by the younger generation, who accuse her and fellow politicians of remaining idle for too long to avoid a climate crisis – and of favouring German industrial interests over climate action. Many say Merkel’s long-standing international engagement for emissions cuts stands in contrast to lacklustre efforts at home.

Under Merkel, “climate policy has gone through many twists and turns and we almost wasted the decade between 2010 and 2020,” says researcher Ottmar Edenhofer, who has advised the chancellor on climate policy. “We could have really used those ten years. If we had worked well, we wouldn't be under so much pressure now – it's already a huge transformation.” Merkel’s government did get a lot done in the end, adds the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC).

However, this was not through Merkel’s proactive leadership, he says, but largely forced by the Fridays for Future protests, a landmark climate ruling by the Constitutional Court and guidelines set by European agreements. These included a coal exit plan, a new climate law with the target of climate neutrality by 2045, and a national carbon price on transport and heating fuels.

I have always had the feeling that when she was in the room with other heads of state and government that there was one there who really cared and understood why this was important.

“I understand that many people, especially the younger ones, are impatient,” says Edenhofer, but adds that Merkel had often worked against “an incredible number of influences from all directions” and held her course” during laborious processes like convincing the G7 and G20 leaders of more ambitious climate targets.

Media dubbed Merkel the “climate chancellor” around two years after she took office. In 2007, she made the issue a theme of Germany’s presidency of the EU Council and as host of the G8, eliciting climate target agreements from both forums. Photos from her visit to Greenland’s melting glaciers from that same year helped cement that image.

Merkel says that climate action has been a big part her political life since 1994 when she became environment minister. “The issue of global warming is, in my view, one of the most important environmental issues we have to deal with,” she said in an interview with Deutsche Welle in 1995. As environment minister of the host country, Merkel was the president of the first UN climate change conference COP, held in Berlin that year. She was reportedly involved in the negotiations also at working level, leading to what was eventually typical of her international leadership style: overnight talks with “sleep-deprived delegates” that eventually culminated in agreements.

Moderator among international leaders “who really cared and understood”

Merkel has often played a key role in finding compromise when national leaders met to discuss climate policy – be it at the G7 or G20 summits, or within the European Union, and she is also seen as an expert on climate issues.

“I have always had the feeling that when she was in the room with other heads of state and government that there was one there who really cared and understood why this was important,” says Connie Hedegaard, first European Commissioner for Climate Action from 2010-2014 and former Danish environment and climate minister.

Before climate became a top issue for most government heads, adds Hedegaard, Merkel’s experience was a big advantage. As environment minister and as a key player in the 1997 the Kyoto Protocol negotiations, “and maybe also because of her background as scientist,” she understands the importance of the issue, says the Danish politician.

Merkel has also earned a reputation as a highly respected international stateswoman, one who has championed multilateral cooperation, especially during the U.S. presidency of Donald Trump when many pundits dubbed her the “leader of the free world”. A Pew Research Center survey last year showed confidence in Merkel’s ability to manage world affairs was at an all-time high in several countries.

Her approach is that you cannot move forward without compromise. This distinguishes her from other politicians who tend to think in terms of victory and defeat.

Merkel has a reputation as a skilled moderator who can keep dialogue open even at times of dissent. Hedegaard remembers the difficult negotiations for 2030 EU climate and energy targets in 2014, where some member states had reservations, including Poland. “Merkel personally played a role in bringing Poland on board. Time and again she cared that the links between Berlin and Warsaw were open. Where nobody else could go to the Polish leadership, she had that dialogue.”

This special knack sets her apart from other world leaders, and could actually be a more lasting legacy for future leaders than her climate milestones. “Her approach is that you cannot move forward without compromise,” says Andreas Rinke, chief correspondent Berlin at news agency Reuters. “This distinguishes her from other politicians who tend to think in terms of victory and defeat.” Rinke knows Merkel well. Nicknamed the “Chancellor-Watcher”, he first interviewed her before she was sworn in in 2005 and accompanied her on more than 50 foreign visits over the years.

Compromise often takes time and by definition does not satisfy maximum demands, like those from climate activists. With Merkel, progress happens step-by-step and is process-driven, says Rinke. “She has a certain scepticism towards people who promise that there can suddenly be the big breakthrough to a problem.”

“Politics is what's possible.”

Merkel’s style rankles with some. Supporters see it as a “model of rational, steadfast leadership”, helping steer Germany and the EU through many crises during her four terms – the 2008 financial crisis and economic downturn that followed, the 2015 migration crisis, and the coronavirus pandemic, to name a few. “Over the course of 16 years, she has dedicated most of her political energy towards nullifying crises that could have spiralled out of control,” Philip Oltermann recently wrote in the Guardian.

Critics accuse her of acting only when pushed, of procrastinating and dithering – waiting until a debate has unfolded and everyone weighed in before making any decisions. They say she lacks vision or the will to push through grand ideas of her own.

“I sometimes don't know if vision is what politicians should do,” she remarked at COP1 in 1995. “Politicians shouldn't promise what they can't deliver.” (She made a notable exception to this in promising Germany would reach its 2020 climate target during the 2017 election campaign.) Fourteen years later, in presenting her government’s comprehensive plan to reach 2030 climate targets, Merkel explained her view of politics on the one hand, and “science and also impatient young people” on the other – referring to the Fridays for Future protesters blocking the streets outside the building: “Politics is what's possible.”

Merkel’s style is 'leading from behind' with an extraordinary sense of opportunity. She doesn't create the opportunities -- she seizes them.

Merkel needed support from the political centre, says researcher Edenhofer. “That's what some outside observers underestimate, how far away the political centre was even in 2019 from recognising the necessities,” says Edenhofer.

Merkel’s style is "leading from behind” with an extraordinary sense of opportunity, he says. “She doesn't create the opportunities -- she seizes them.” And if a compromise turned out to be worse than what was necessary? “In politics you sometimes have to be patient. The first compromise can be improved.” Edenhofer notes the constitutional court’s climate ruling this year, which spurred the government to increase climate targets. “The Court decided in April to force politicians to make credible commitments. This gives the politician the opportunity to make the necessary possible, which Merkel probably thought was a good thing.”

Merkel’s style has thus elicited few surprises in climate policy, says journalist Rinke, with one notable exception: Her government’s flip flop on nuclear plants which came after Japan’s Fukushima nuclear disaster. Having just decided to extend their life, Merkel said Germany would quit the technology days after the disaster.

Fukushima changed her thinking, says Rinke. Until then, Merkel had thought of the technology as a more climate friendly alternative with manageable risks. “It was surprising for many to see the determination with which Merkel reversed 180 degrees in the other direction.”

This took other EU member states by surprise, recalls former Commissioner Hedegaard. “That was a very unilateral move, which a lot of neighbouring countries were not happy with, to put it mildly.”

A wasted decade in climate action

As Merkel’s last year in office draws to a close, her legacy may now be tainted by a strong rebound of emissions after the coronavirus crisis. Instead of presenting a perfect image of Merkel’s goal of a green recovery, the rise would throw the country off course to meet its 2030 target. In addition, Germany faces huge energy transition tasks: it must urgently ramp up renewables expansion, kick-start the transition in industry, develop its power grid, tackle costs, and become more digitalised – to name just a few challenges.

When Merkel took office in 2005, the country’s famed Energiewende was already in full swing. The nuclear exit had been agreed by the Social Democrat and Green coalition after the 1998 election. Germany’s renewables law with feed-in tariffs for wind and solar parks had been in force for five years, and ten percent of Germany’s gross power production came from renewable sources.

By 2020, this had risen to almost 45 percent. Installed electricity generation capacity of wind, solar, biomass and hydropower rose from less than 30 gigawatts (GW) in 2005 to more than 130 GW today.

It’s hard to say how much of this progress is due to Merkel’s policies, but critics say her climate and energy policy has for the most part been lacklustre. Expansion of renewables has recently stalled, due to regulatory hurdles, long permit procedures and the auction system for renewables support which Merkel’s government had introduced to replace fixed feed-in tariffs. Greenhouse gas emissions under Merkel’s reign remained largely unchanged before a steady decline during her last term.

National interests and the ‘auto industry chancellor’

Critics also say she has actively prevented more progressive decisions when national interests were at stake – especially those of industries like coal or cars. She was labelled ‘auto industry chancellor’ after reportedly personally intervening in 2013 to prevent stricter CO2 limits for cars at EU level.

“When we finalised trilogue negotiations between the Commission, Parliament and Council about CO2 emission standards for cars in overnight talks in 2013, Germany was against it, but the agreement went through,” recounts former Commissioner Hedegaard. “Later that day, however, the German government made calls at very, very high level to other member state governments to make them change their minds.” The process was delayed by a year until after the German election. “To me that shows that when really big German interests were at stake it was a tough power game,” says Hedegaard.

The label has stuck until today: “Angela Merkel is the true automobile chancellor,” wrote Max Hägler and Christina Kunkel in Süddeutsche Zeitung when reporting on the 2021 opening of Europe's largest auto show IAA. They recount how the room full of industry representatives spontaneously applauded the chancellor when she entered the venue. “This has probably never happened at a car show before.”

Merkel has also supported the contentious Russian-German natural gas pipeline project Nord Stream 2 – in the face of heavy criticism from almost all European neighbours and international partners like the U.S., and despite the climate consequences of such a fossil gas link, designed to last for decades. The reason is that Nord Stream 2 promises an abundant low-cost energy supply to German industry and consumers, write Matthias Matthijs and Daniel Kelemen in Foreign Policy. Merkel “is clearly willing to look past [Russian president Vladimir Putin’s] repeated and brazen violations of international law and human rights norms if it means cheaper energy for German factories and homes.”

Will Merkel be remembered as climate chancellor?

Researcher Edenhofer says Merkel’s legacy as climate chancellor is yet undecided. If future governments are successful in combatting climate change, then Merkel will be “judged and honoured as a precursor,” says Edenhofer. If not, “her politics will be described as merely the art of the possible,” says Edenhofer. “Historical grandeur is only revealed in the success of future generations, as is so often the case.”

Because climate action is a top issue now, the public may be more critical, notes journalist Rinke. “The view of the last 16 years is more critical than it would have been 4 years ago, when most people were concerned with completely different problems,” he says.

Merkel has not publicly said what she considers her biggest contribution, Rinke says. “My impression is that it is Europe on the one hand – that Europe has not only stayed together but also developed further – and on the other hand furthering sustainability and securing the future through areas like climate action or technology development.”

“It's not that she thinks she was the game changer, but she wants to have driven development in the right direction for 16 years,” says Rinke.

Germany must weigh in on the EU Fit for 55 package and a chancellor must have the willingness to spend time and energy and diplomatic capital. It’s really hard to see who else could fill that space.

Having entered the final four weeks, the German election race is wide open as the Social Democrats have caught up with the conservatives in the polls, with the Greens trailing slightly behind. This could mean difficult and long coalition negotiations after the vote on 26 September – giving Merkel a couple more months to govern – albeit as a lame duck chancellor.

Looking ahead, the next government will pick up where she left off, with the G7 presidency 2021 and the EU negotiations on the ‘Fit for 55 package’ of climate and energy legislation. The package will be difficult to get through the member states, especially some of the eastern countries, says former Commissioner Hedegaard. In her view, Germany must weigh in and a chancellor must be willing to spend time, energy and diplomatic capital. “It’s really hard to see who else could fill that space. We need Germany to play a strong role.”