Lingering nuclear dissent between Paris and Berlin obstacle for EU renewables push

*** Please note: this article is part of a CLEW cross-border cooperation, exploring the Franco-German approaches to climate and energy and how these affect the vision of the EU’s energy future. You can find the full dossier here.***

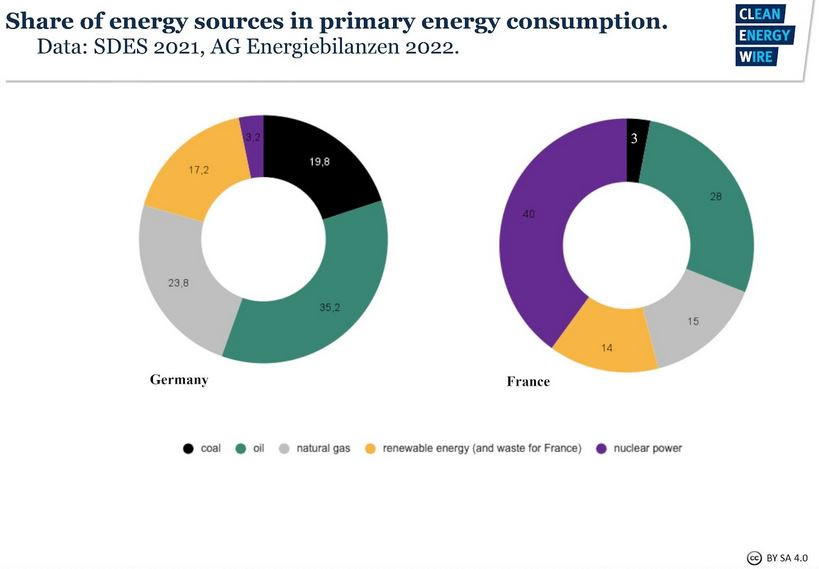

The role of nuclear power in Europe’s transition away from fossil fuels has been a point of contention between French and German governments for a long time. In the year 2000, Germany decided to phase out nuclear energy and, despite temporarily backtracking on its decision before the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, ultimately completed its nuclear exit in April 2023. France, on the other hand, has the highest share of nuclear in the energy mix of any country in the world and, despite temporarily considering to radically cut its reliance on nuclear power after Fukushima, has committed to building many new reactors as part of its bid to meet European climate targets and net-zero emissions by 2050.

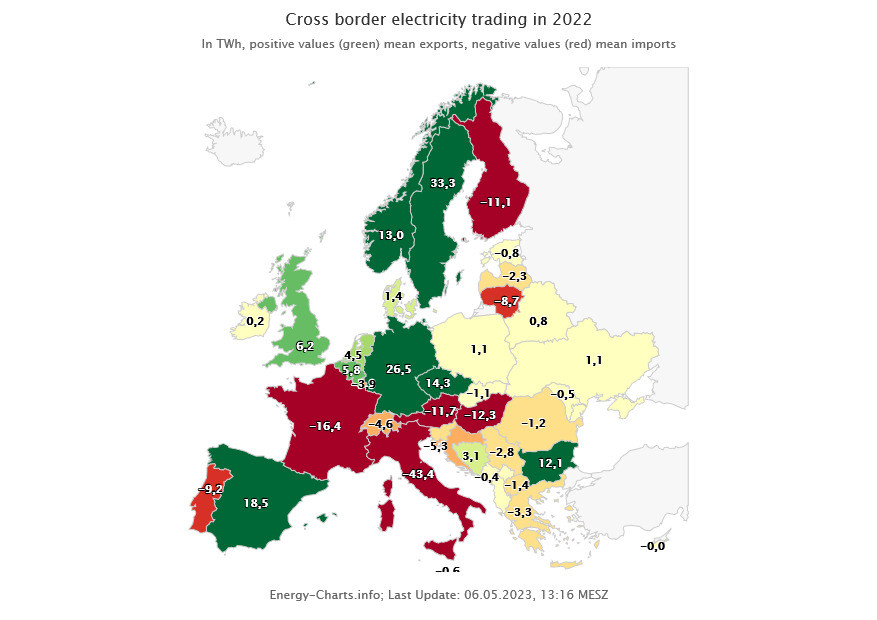

Despite the stark differences in the energy strategy of the EU’s two most influential member states, consecutive governments in Paris and Berlin long agreed to disagree. In line with national prerogatives for EU member states to decide on their own energy mix, both countries quietly traded electricity without asking whether electrons were generated with nuclear reactors, renewables or fossil fuels. Yet, the 2022 European energy crisis and the increasing need to formulate a strategy to meet sustainability targets in the EU’s Green Deal have undermined this arrangement. The crisis also showed that disputes about nuclear energy between France and Germany come with major implications for the strategic positioning on energy and climate policy of the whole EU.

Warning against stranded assets no impediment to French nuclear push

Debates about energy in the EU are never only about energy, at least according to Xavier Moreno, president of French think tank Ecological Realities and Energy Mix Study Circle (Cereme) and former vice president of French utility company Suez. “There is a mixture of interests and ideology in the positions taken,” Moreno said. Industry, policymakers, and activists all jostle for influence over the debate with their own goals in mind, sometimes at the expense of focusing on the core of the problem: making Europe’s energy system fit for the future. “These are very technical questions, and when politics gets hold of them, it is quite easy to make assertions that have no relation to reality,” Moreno said.

In a joint attempt to provide greater technical clarity on the nuclear power debate, French think tank IDDRI and German Agora Energiewende set out already in 2018, to understand how nuclear energy will influence the transformation of energy systems in both countries. They found that if a high share of coal or nuclear based conventional power capacity stays online in both countries, this will likely delay the time when market prices allow renewable power operators to cover their production costs and run operations at a profit. Their research also found that exporting surplus electricity with conventional plants bites into renewable power investments abroad. At the same time, the growing share of renewables would eventually render most conventional plants unprofitable. “In order to avoid stranded assets, it is essential to gradually reduce conventional capacities,” the bi-national report concluded.

For Moreno, these technicalities fail to consider a crucial point the in the argument for nuclear power: “The only thing that matters is to get out of carbon-based energies,” he argued. Germany’s plan to replace coal capacity with gas would not deliver on this key premise, Moreno said. Moreover, the country's all-renewables approach was complicated by a lack of viable electricity storage technologies. “Technically speaking, it would be necessary to store up to 20 percent to be able to smoothen renewable power supply.” Those who believe that this will be possible through a combination of different storage options are chasing “a dream,” Moreno argued.

With a view to the summer of 2022, when more than 30 out of 56 reactors were shut down during the summer because of maintenance and turned France into a net electricity importer for the first time in 42 years, Moreno said it would be “absurd” to criticise nuclear plants for not being flawless in regards to supply gaps. “"Over the last 60 years, minor malfunctions have occurred, but we have always easily and quickly addressed them,” he said. This is why France would need excess nuclear capacity in case a backup is needed. However, the challenge now is to ensure that the French nuclear industry is fully restored within the next 30 years to retain technological leadership, he added.

Timeline of recent nuclear power developments in France and Germany

|

FRANCE |

GERMANY |

|

-2007: launch of the Flamanville European Pressurised Reactor (EPR) construction site (opening scheduled for 2012, still not in service as of 2023)

-2015: Energy transition bill (reduction of the country’s share of nuclear energy from 75 to 50 % by 2025).

-2017: previous objective is eventually deemed unrealistic.

-2019: the Energy-Climate Act extends these targets to 2035. -2023: nuclear acceleration law. Removal of the target of reducing the share of nuclear power in the electricity mix to 50% by 2035.

-By 2040: probable shutdowns (up to 9) of aging second-generation nuclear reactors.

-By 2050: Construction of 6 to 14 EPR2 considered. |

-1998: “Nuclear consensus”.

-2000: government commits to phasing out nuclear power and starts shutting down plants.

-2002: Amendmentof the Atomic Energy Act classifies nuclear power a necessary ‘bridging technology’ toward a renewables-based energy system.

-2009: “phase-out of the (nuclear) phase-out” – extension of the operating time by eight years for seven nuclear plants and 14 years for the remaining ten.

-2011: decision to phase out nuclear energy reinstated (shutting down eight nuclear plants for good and limiting the operation of the remaining nine to 2022).

-2015 : E.ON announces that as of 2016, it would sell off its fossil and nuclear operations.

-April 2023: shutdown of the last three nuclear power plants in Germany are taken off the grid. |

Since the bilateral analysis of stranded asset risks in the power sector was carried out, Germany has initiated its coal power phase-out, the power generation technology leaving the biggest mark on the country’s carbon footprint. While the use of coal in the country is set to end no later than 2038, there is no fixed schedule yet for ending the use of natural gas, although the goal of climate neutrality by 2045 puts a clear limit on using the fuel. For nuclear, which has no direct carbon emissions and allows France to have one of the lowest per capita emissions levels of all wealthy economies, no such limits have been conceived of, meaning investments in decarbonisation do not necessarily end up in expanding renewables.

On the contrary, France hopes to take advantage of its vast fleet of reactors to electrify parts of its energy system with low-carbon nuclear energy. While the government considers extending the runtime of certain plants to at least 60 years, and building up to 14 new European Pressurised Reactors (EPR) for commissioning after 2035, it is also anticipating several reactor shutdowns during the 2040s. In line with European renewable power plans, Paris therefore also plans to accelerate the development of its wind and solar capacity. However, as of 2023, it still lagged behind its renewable energy targets set for 2020.

EU Green Deal funds could help implement France's nuclear plans

France announced its nuclear plans shortly before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. At the time Germany's economy and climate minister Robert Habeck argued that France's renewed focus on nuclear power would not yield the benefits Paris was promising. France pursued a "state-directed and capped energy supply by an outdated industry” that high costs and technical uncertainties render increasingly unprofitable. “We will meet again in 2030,” Habeck said with a view to his government’s plans to achieve a share of 80 percent renewables in the power mix by that year. More than one year later, his French counterpart, economy minister Bruno Le Maire, showed no signs of remorse. On the contrary, he insisted his country “will not give up any of the competitive advantages linked to nuclear energy.” Its reactors underwrite France’s “economic sovereignty and independence”, Le Maire said, declaring attempts to curb its use “a red line” for Paris.

Beside offering the country a source of low-carbon energy, nuclear power currently represents France's 3rd-largest industrial sector and an important market for exports and industrial prowess. Moreover, nuclear power is regaining popularity among the French people: a 2023 survey showed that some two thirds of the population in France had a favourable view of the technology, up from about 40 percent in 2016. This is despite divisive questions regarding nuclear waste and safety that have been flagged since the 1970s and continue to the present day.

Nuclear safety concerns continue to occupy experts in France as much as anywhere. In mid-2023, about 800 French scientists warned against the risks of the country’s new nuclear programme, pointing to questions of radioactive waste management, which remain largely unresolved in most of the EU, including in France. The scientists also warned against risks of accidental contamination or meltdown. Even though France has thus far not seen any major nuclear accident (only level 4 has been reached on a scale going up to 7), the risk of a larger malfunction or mishandling of nuclear energy components in the supply chain can never be entirely protected against. An earthquake in western France in June 2023, one of the most powerful ever recorded, or the ongoing involvement of nuclear sites in the war in Ukraine serve as reminders of the unpredictable risks that reactors may face.

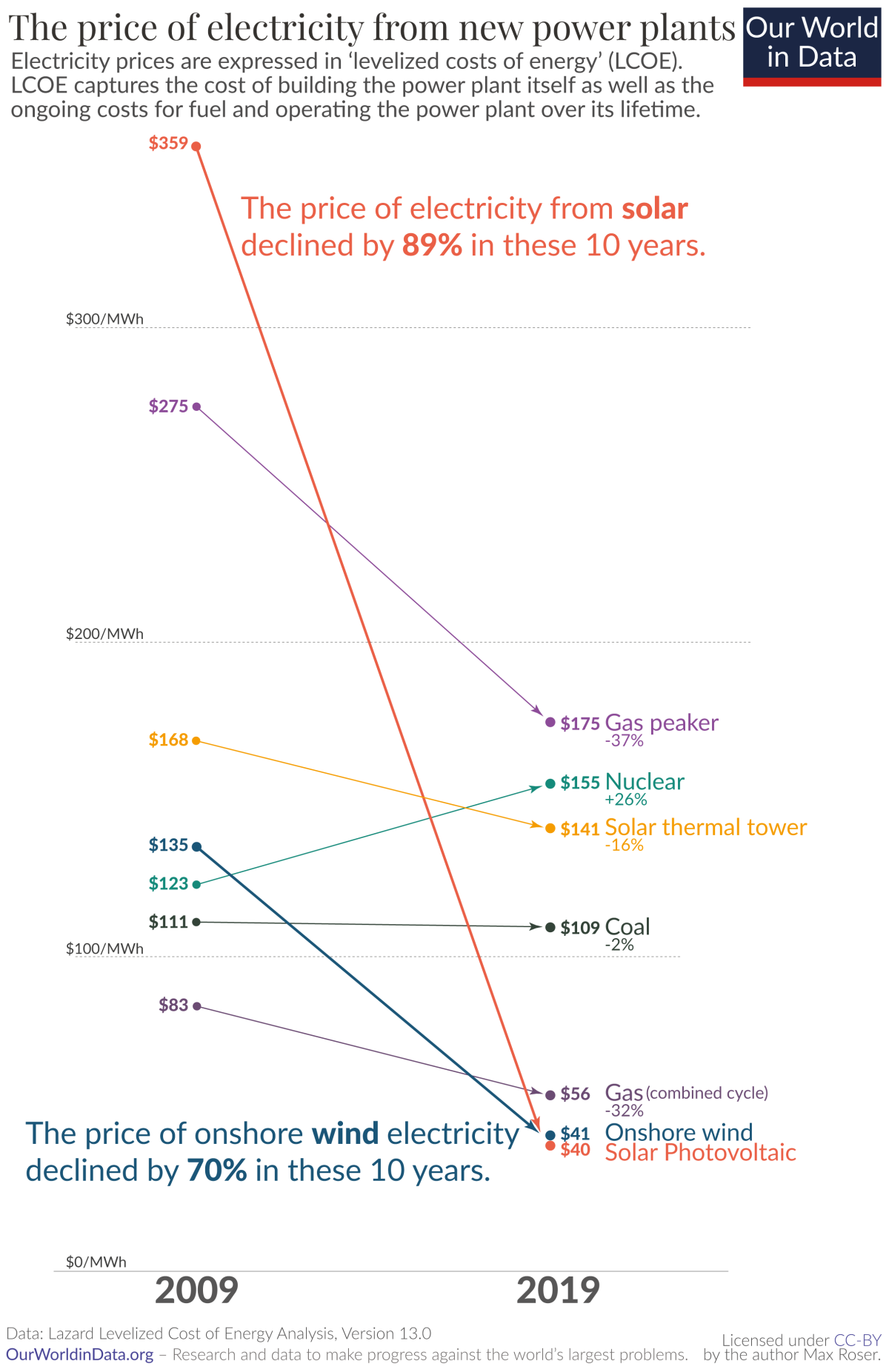

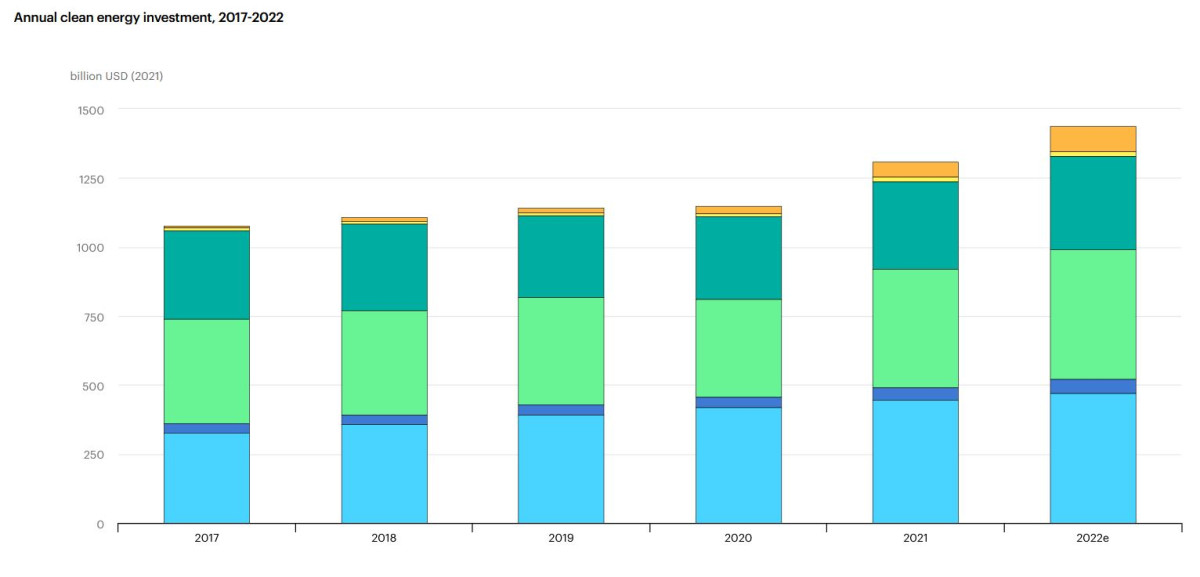

Securing funding from Brussels for the major buildout is regarded as a substantial challenge to France’s plans. Investments in renewable energy have been on the rise in the country since 2016, as costs have gone down. According to data by U.S. investment bank Lazar, prices per megawatt hour (MWh) produced with renewables have dropped dramatically between 2009 and 2019 alone, while those for nuclear power went up. Solar power generation costs dropped nearly 90 percent to 40 dollars per MWh and onshore wind 70 percent to 41 dollars per MWh. Nuclear power costs per unit in the same decadec increased 26 percent to 155 dollars per MWh. Meanwhile, nuclear power construction costs have risen, while future EPR costs are still uncertain. The sharp rise in interest rates has made building new nuclear plants even more expensive, compounded by reactor construction delays. Nuclear plant operator Electricite de France (EDF) estimated the cost to be at least 51 billion euros. A convincing policy framework allowing Paris to classify the nuclear bill as an investment in the EU Green Deal could thus send and important signal to potential nuclear power investors.

Determined to achieve an inclusion of nuclear reactors in European renewable energy plans, France brokered a deal with Germany to include nuclear power within the EU taxonomy of sustainable investments in mid-2022. Germany successfully insisted on including natural gas investments in the sustainable finance framework, which it regards as a ‘bridge technology.’ Germany's poisition was fiercely criticised by climate NGOs and many sustainable finance experts. Since the taxonomy deal was brokered, the EU’s staunchest opponents nuclear power’s inclusion, such as Austria and Luxembourg, have warned they will take legal action against it.

France also pushed to include nuclear energy in the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED), a target it achieved after protracted negotiations that saw the country form a ‘nuclear alliance’ with sympathetic governments and in opposition to Germany’s insistence on limiting funding to renewable power installations. The French energy minister, Agnes Pannier-Runacher, in mid-2023 said it was “regrettable that Germany is applying the brake” on reforms that enhance nuclear power’s role, arguing this would fail to take the position of a majority of EU countries into account.

Germany’s priorities largely in line with international trends

But the lack of a shared vision extends beyond the bilateral relationship of France and Germany. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen declared in spring 2023 that nuclear power was not a ‘strategic’ technology in reaching the EU’s climate goals. Nevertheless, the technology remains at the heart of many debates at the European level. This includes the Fit for 55 Package, nuclear-derived pink hydrogen (both countries agree on more hydrogen production but disagree over the role synthetic fuels will play),the Net Zero Industry Act, and the electricity market design reform. Stephane Bourgeois, European relations and policies manager at French NGO negaWatt said that with its insistence on nesting nuclear power firmly within EU initiatives across the board, France had shaped the terminology to suit its national aim of securing funding for new reactors. “This is a pity, because it takes away the focus from the common ground and it costs everyone a lot of energy,” Bourgeois argued. With its non-negotiable position on the technology, “France is in the process of exporting to the European level the effect of slowing down the transition efforts that nuclear power has long been making in its own energy and climate strategy,” added his colleague Yves Marignac, head of the nuclear and fossil fuel expertise unit at negaWatt.

Proponents of nuclear power in France have routinely fended off this kind of argument by arguing that German insistence on renewables is a targeted attempt to exclude nuclear power. During an inquiry into France's loss of energy sovereignty and independence in 2022, Henri Proglio, former president of France’s leading electricity producer and supplier EDF, stated that “Germany's obsession for the past 30 years has been the disintegration of EDF.” Proglio lashed out at German engineering company Siemens for allegedly undermining a Franco-German nuclear power project to develop a new generation of EPRs. Siemens withdrew from the joint project at a time when Germany as a whole reaffirmed its determination to phase-out nuclear power after the Fukushima disaster. However, Germany’s industry association BDI said it remains ready to cooperate on nuclear research, for example in the international ITER nuclear fusion research facility in southern France. Also Germany’s research ministry in mid-2023 announced the government would make a “strategic reorientation” and expand nuclear fusion research.

“The two energy strategies are based on fundamentally different, incompatible choices. For the moment, imagining a reconciliation is a bit of a long shot,” said Mycle Schneider, a long-standing German nuclear power critic based in Paris, who is also the coordinator of the World Nuclear Industry Status Report. “Since France has decided to create camps with its alliance initiative, it led to a situation where Germany was constantly in the position to react,” he argued. “It rather cemented these differences, politically speaking,” Schneider argued.

Nuclear power proponents in France and elsewhere have repeatedly labelled Germany’s insistence on exiting nuclear power and towards shifting renewables imprudent or even reckless during the energy crisis. However, it is overall more in line with international trends than a nuclear expansion, as the money raised for new reactors remain a fraction of what is spent on wind turbines, solar panels and other renewables in global clean energy investment figures over the past few years. “The main question that arises in all this discussion about present and future options for the energy problem is really feasibility,” said Schneider. “The German strategy is based on existing technical options whose feasibility has been demonstrated, that are economically and industrially competitive. Before 2030, we will see whether Germany can feed its electricity network, essentially from renewables, or else it would be a huge failure,” Schneider argued. The French nuclear-newbuild is “simply not feasible at that time horizon,” he added.

Nuclear-heavy French grid must allow EU-wide renewable power trading

The choice between having a decentralised and flexible system based on renewables or a centralised grid that is based on a nuclear baseload will have big implications for the functioning of Europe’s integrated energy market, according to Michael Bloss, member of the European Parliament for the German Green Party. “The more European power markets become integrated, the more this difference is becoming a problem,” he argued, pointing to the ongoing debate about an EU electricity market reform. Bloss identified one example: the dispute over so-called gate opening and closure times that regulate the intervals for power trading on the European electricity market. For a renewables-based system, supported by Germany, short intervals of 15 minutes or less are favorable to ideally allocate renewable output based on short-term weather forecasts. By contrast, France has proposed longer intervals of one hour, adapted to the constant output of nuclear power. “Both approaches clearly clash with each other here and larger theoretical differences become concrete technical challenges,” the Green MEP argued.

Rainer Hinrichs-Rahlwes, European policy expert for the German Renewable Energy Federation (BEE) lobby group, affirmed the concerns over incompatibility. “Nuclear power plants and their inflexible output can cause grid congestion, the opposite of what is needed to accommodate large shares of wind and solar in a modern and flexible grid system,” he said. “Flexibility is a key requirement for energy markets and of course also for grid infrastructure of a renewable-based power system,” Hinrichs-Rahlwes said. In effect, France’s insistence on a nuclear baseload amounts to “a burden and not an asset for a smooth energy transition in Europe,” he argued.

Irrespective of its nuclear capacity, France had to find a way to allow electricity from renewable power sources “to be system defining and flow freely through its grid,” for example to send Spanish solar power to northern Europe, the renewable power lobbyist added. This is not possible if an inflexible nuclear baseload congests the system, particularly when a lot of cheap wind and solar power is available, which would then need to be curtailed, he argued. “Without such a major paradigm shift, the country risks becoming a nuclear ‘Gaulish village’ surrounded by neighbours supplied reliably by cheap sustainable renewable energy” that come to help when French nuclear reactors fail to deliver.

While electricity imports to Germany almost exclusively result from price differences, power imports to France were vital to keep the system running in 2022, said Bruno Burger, energy system researcher at the German Fraunhofer ISE institute. “Renewables in Germany are not yet ready to generate power surpluses on their own, but they certainly help to ensure that the lights don’t go out in the European system as a whole,” he said. In early 2023, much higher future electricity prices in France suggested traders expect a pattern similar to the previous year to prevail, Burger pointed out. Even if French power customers are shielded from the higher prices through state support, energy system costs as a whole are increasing, the researcher said.

Germany and France “may never agree” but must move on

At the same time, climate change and associated extreme weather events such as water shortages exacerbate some of the existing challenges for nuclear power production. French nuclear reactors account for 12 percent of total water consumption in France, and cooling with river water that is then discharged back into the stream can put enormous stress on local ecosystems, especially during heat waves. The creation of new cooling systems to evacuate the heat while reducing the use of river water are in development, but could involve additional costs. Jules Nyssen, president of the French Renewable Energy Syndicate (SER) argued that “France has the peculiarity of having long confused its issues with energy to be electricity issues alone.” Regarding the electricity sector, “we had a nuclear fleet that ensured a decarbonised and sovereign production,” Nyssen said, arguing that the country discounted the priority of systemic changes as a result. “It wasn't until the events in Ukraine, which only revealed a more latent crisis, that we realised that there was a global energy issue.” In France, “we need to get across to the public the idea that even with a lot of nuclear power, we can't do without electric wind turbines.” Given Europe’s climate targets, it would make sense to keep taking advantage of existing nuclear capacities without necessarily extending it in the future, he argued.

Pascal Canfin, French MEP for liberal Renew Europe, furthered the view that nuclear’s formerly unquestionable role in France has softened. “In the past, the nuclear lobby in France has prevented the development of renewables. I sincerely believe that this is no longer the case today, we are moving on,” he said in an online panel on Franco-German nuclear positions. If France and other European countries were to fully integrate into a flexible European system, this would also greatly alleviate concerns over oscillating renewable power production. Today, the variability of renewable energy is managed at European level by fossil-fired power plants, a report by French grid operator RTE noted, supported by hydro power, particularly in France, Switzerland and Scandinavia.

A report released by NGO negaWatt in 2023 on European energy collaboration found that climate neutrality is within reach through a combination of energy savings, efficiency, and renewables. By contrast, reliance on nuclear power would require a hybrid system of centralised nuclear plants and scattered solar arrays and wind turbines. In a 100-percent renewable scenario, storage production to meet this variability would be very low and result in lower total system costs, the negaWatt report concluded.

Despite the growing role of renewables in France, in the long-term France and Germany might have to “acknowledge the fact that we may never agree on nuclear”, said Phuc-Vinh Nguyen, researcher on European and French energy policies at the Energy Centre of the Jacques Delors Institute. Instead, a form of ‘two-speed Europe’ might emerge on this question, he added, allowing those who wish to go ahead with nuclear, while allowing those who don't want it to do without, in order to prioritise the aim of phasing out fossil fuels. “The European elections will act as a judge of peace as to the direction that will be given.”