Carbon offset market booms despite nagging greenwash concerns

The next world tour of pop band Coldplay will have net-zero emissions, German housing giant Deutsche Wohnen wants to be climate-neutral by 2040 while car maker Volkswagen and sports brand adidas are aiming for 2050 at the latest. Setting climate targets has not just become a must for governments but also for companies. This has triggered a boom in the voluntary carbon offset market.

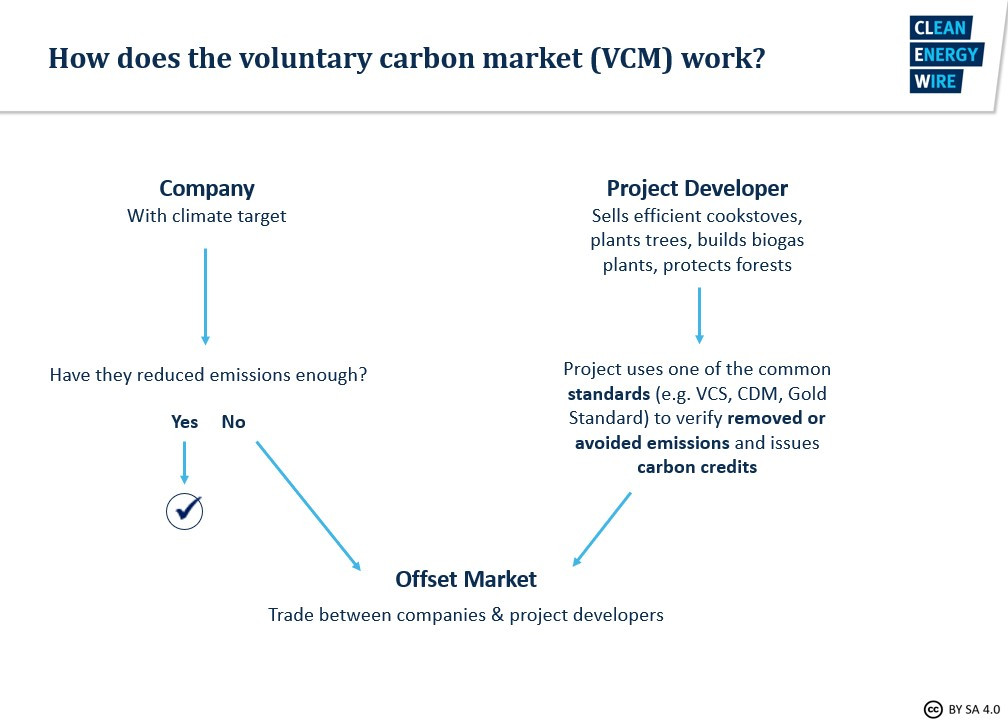

Companies are setting net-zero targets in droves because consumers expect them to and because reducing emissions and adhering to internal carbon prices are making businesses more future proof. But not all emissions can be avoided, especially not within a few years, many companies find. So to put them on track to their carbon neutrality goals, or to label products as “climate neutral”, many companies use emission reduction projects or carbon credits to offset their operational emissions with climate action elsewhere, most commonly in developing countries.

Financing energy efficient cookers in Nepal and Madagascar, installing wind turbines in India, operating biomass plants in Nigeria or protecting rainforests in Indonesia all help avoid emissions in these countries. For these efforts, project developers sell carbon offset credits on the voluntary carbon market (VCM). To proof the offset’s quality to customers, many projects use an external quality standard provider which checks the emission reductions achieved and also issues the credits that the project developer can sell. To count the emission reduction towards its net-zero goal, a company has to delete the credits it buys to ensure that no further use of the same tonne of CO2 can occur.

According to a report published by Ecosystem Marketplace, the global voluntary carbon market (VCM) is on track to reach a new market value record of over one billion USD for the first time in 2021 and reach 50 billion USD in 2030.

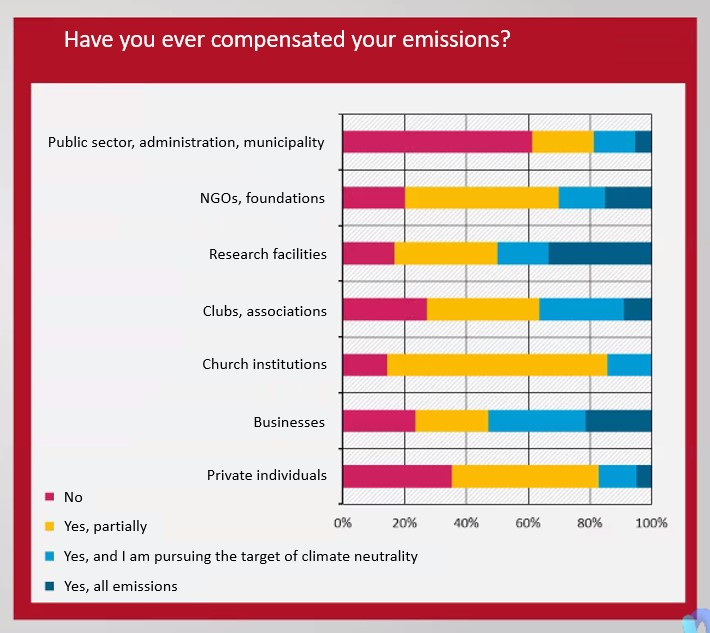

New, preliminary data compiled by consultancies adelphi, NewClimate Institute and sustainable AG for the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) show that most companies surveyed in Germany use carbon offset credits to (partially) compensate emissions. Businesses and private individuals both use CO2 credits to compensate flights, but more and more companies also resort to them as part of their overall climate strategy.

“Many of our large clients needed a few years to find their feet after Paris, and now they have gradually developed climate protection strategies, set their own goals, and then decided to do offsetting as well,” Dietrich Brockhagen, founder and CEO of German compensation project developer atmosfair, told Clean Energy Wire (CLEW), adding that he expected the market for business offsetting to roughly double every two to three years or so.

In Germany, the number of certificates sold rose from 10.3 million to 71.8 million tonnes CO2 between 2016 and 2020, the survey conducted for the UBA showed. “All suppliers reported a similar trend – by October, they had already reached their volume from the previous year, and the trend continues to be positive,” Markus Götz from the Munich-based consultancy sustainable said at a workshop in September 2021.

.](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/mckinsey-global-demand-vcm-2050.jpg?itok=NTmRn8zy)

But while “compensating” emissions on the voluntary market becomes more and more mainstream, there is also recurrent and strong criticism of the practice.

Carbon offsets are sold at prices ranging from one to more than 100 euros in the German market. The projects are certified according to a range of different standards called CDM, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve or VCS (by Verra) and receive a certain amount of carbon credits for one tonne of CO2 each. Over 90 percent of voluntary carbon credits worldwide adhere to the five most common standards. “The quality of the certificates is quite hit and miss. And often it is very difficult – even for us researchers – to distinguish between a good and a bad carbon credit,” Lambert Schneider from the Institute for Applied Ecology (Öko-Institut) told CLEW. One of the biggest issues is the so-called additionality – the projects can only be used for compensation if they would not have been realised without money from the certificates, otherwise the project would not bring any additional climate protection.

Many standards, little reliability

For carbon credit users in Germany, the quality of the standard is most important for their decision (40%) which offset project they choose, adelphi found. The price, on the other hand – which in 2015 was named as the most decisive factor – is not their main concern.

German carbon credit buyers prefer projects that invest in renewable energies, followed by afforestation and sustainable forestry projects, energy efficiency and agriculture, e.g. carbon farming projects. The public sector uses carbon offsets the least, mainly because they are held back by political decisions that need to be taken first, participants told the researchers.

The certification standards are meant to ensure that criteria such as additionality are met and it is the standards that customers have to rely on to make sure that a carbon credit they bought really embodies a tonne of avoided or removed CO2. “Unfortunately, there isn’t the one standard where everything is perfect. It depends a lot on which standard is used for which type of project,” Schneider said. While some standards are very good at ensuring additionality, others have very strict requirements when it comes to the social impact or environmental effects that projects can have. Together with the World Wildlife Fund U.S. and the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), Schneider is developing a tool to compare and rate different types of carbon credits.

Info-Box: Main quality criteria in the voluntary carbon market (VCM)

There is no central control or government regulation for the voluntary carbon market. Companies buy the carbon credits sold by the various project developers to neutralised emissions in their operations, value chain or outside their direct sphere of influence. The projects are – often but not always – quality controlled by one of the leading standards (e.g. VCS by Verra, Gold Standard, CDM). To ensure integrity of the traded emission offsets, certain criteria are commonly applied and checked (by the standards):

Additionality: Without the project activity, i.e. the money from the carbon credit sales, significant volumes of carbon dioxide would have been released.

Permanence: The avoided emission of a greenhouse gas is non-reversible (for a certain amount of time), thus making the carbon offset permanent. For this the different standards set very different targets.

Avoid leakage: The project may not result in merely displacing the release of greenhouse gasesto outside the project boundaries, e.g. that instead of the protected forest another forest was cut down.

The standards run audits of the projects, to ensure these criteria are met. For this they often use other auditing firms. There are intricate calculation methods to account for a certain amount of carbon leakage or loss of permanence in every project, so as to prevent selling more carbon credits than tonnes of CO2 were reduced.

“Permanence” is another major problem, with many land-based and forestry related CO2 reduction projects being in danger of losing all their stored or avoided carbon if a fire breaks out or other natural disasters happen. Again, there are stark differences between the vendors and standards in the market: While Climate Action Reserve in California requires that the forest must remain standing for 100 years to be used for compensation, there are others that require a guarantee for five or 10 years only or not at all, Schneider explained.

A once praised project “Plant for the Planet”, initiated by a German 9-year-old who is still running the NGO as an adult, has come under a lot of fire for using funds on unsubstantiated planting operations in Mexico and has been abandoned by several large business supporters.

When climate neutrality goals and compensated emissions backfire for companies

Improper compensation attempts frequently make headlines. German car maker VW discontinued cooperation with project developer Permian Global after Greenpeace questioned the additionality and permanence of its tropical forest protection and afforestation project in Indonesia. “We see that a large number of these projects are greenwashing and do not actually reduce CO2,” carbon removal expert Karsten Smid from Greenpeace Germany told CLEW.

“It's a real shame when that happens. I can see how much is achieved with our money in the global south. And even if working with offsetting is only the second-best solution from a climate perspective, even the second-best solution can achieve a lot,” Dietrich Brockhagen of atmosfair said.

But the genuineness of the projects generating the emission credits is not the only predicament of the carbon offset market. While some companies use carbon credits to compensate those emissions that they really can’t avoid, others buy them to keep their fossil-based business models alive. Oil giant Shell was selling “carbon neutral” diesel by offering customers to offset emissions by paying a little more at the petrol station, until the Dutch Advertising Code Committee gave it a warning.

The German competition watchdog “Wettbewerbszentrale” has launched several court cases against companies that claim a “100 percent climate neutral production” or “climate neutral” products. These claims give the impression that the company has achieved climate neutrality through emission avoiding and emission reducing measures, while in reality they had achieved the alleged climate neutrality merely as a “mathematical result” through the purchase of CO2 compensation certificates. So far, courts in Germany have ruled that climate neutral frozen potatoes, climate neutral candles and climate neutral plastic bin bags are misleading claims with which the respective companies may not advertise their products. Other cases (e.g. climate neutral heating oil) are still pending.

Many project developers and sellers of carbon credits therefore offer to help their business customers develop a holistic carbon reduction plan that only uses offsets as a last resort, or they develop individual projects in the global south for their customers. “We check their climate action planning and see if it is ambitious enough,” Brockhagen said. If the company doesn’t make enough effort in reducing its own operational emissions, atmosfair reserves itself the right to drop out of the contract.