The carbon balancing act: Emission reduction and removal in the bid for net-zero

Climate neutrality 2045 – the new German climate target means even more emission cuts in even less time, more renewable power, and more energy efficiency wherever possible. This much was immediately clear when Chancellor Angela Merkel’s outgoing government, pushed hard by youth activists and a damning judgement by the country’s highest court, ratcheted up its emission reduction goals in May this year. What is less clear, and what the government has been very reluctant to tackle, is what to do with the residual emissions - those that cannot be avoided, even in the highly electrified future of 2045. This is especially important since the target after 2050 is “net negative” emissions, i.e. removing more CO2 from the atmosphere than greenhouse gas emissions are released into the air.

“The objective of net zero greenhouse gas emissions acknowledges that we will have residual emissions. To achieve the target, these will have to be compensated and this means we will have to deploy CO2 removal,” Felix Schenuit, researcher at the University of Hamburg, told Clean Energy Wire (CLEW).

This view is backed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and features as a given in a much-noticed report by think tanks Agora Energiewende and Agora Verkehrswende, and the Climate Neutrality Foundation. The authors estimate that some 63 million tonnes (t) in residual emissions (95% of emissions compared to 1990 can be avoided) separate Germany from its net-zero emissions goal in 2045. They will arise mostly from agriculture in the form of methane and nitrous oxide from animal farming and fertilisers, from waste treatment, and from industrial processes such as cement making or in the chemical industry.

Info-Box: climate neutral, CO2 neutral, climate positive, net-negative

When looking at residual emissions and the ways to remove them, it is important to understand the difference between the various climate goals that governments and companies have set themselves. These are some definitions on what some common terms generally mean:

Climate neutrality = Greenhouse gas neutrality (Germany 2045, EU 2050) – The goal of climate neutrality refers to the reduction of all greenhouse gases, i.e. not only CO2 but also methane, nitrous oxide, as well as (among others) hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons and sulphur hexafluoride. Climate neutrality is reached when there are net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, meaning that all remaining greenhouse gas emissions are removed by CO2 sequestration somewhere in the planet’s system. When pursuing climate neutrality, the residual emissions are higher because they typically arise from processes (e.g. animal husbandry) that cannot be prevented entirely.

Net-negative (Sweden 2045; Germany after 2050) – Instead of emitting greenhouse gases, net-negative countries are aiming to remove more CO2 from the atmosphere. The definition in the Swedish Climate Law reads: “The amount of greenhouse gas emitted is less than what can be reduced through the natural eco-cycle or through supplementary measures”. Supplementary measures are described as “increased carbon sequestration in forest and land, carbon capture and storage technologies (CCS) and emission reduction efforts outside of Sweden”. While these measures typically remove CO2 (not other greenhouse gases), the calculation of emissions in “CO2 equivalents” allows, for example, methane emissions from the farming sector to be offset by CO2 uptake in forests.

Climate positive means the same as net-negative: Going beyond achieving net-zero carbon emissions to create an environmental benefit by removing additional CO2 from the atmosphere.

Decarbonisation – Refers to the process of reducing the CO2 emissions of an activity. A ‘decarbonised’ company or (global) economy would not emit any fossil CO2 into the atmosphere.

Carbon-neutral (China 2060) – Carbon neutrality means that CO2 (not other greenhouse gases) released into the atmosphere from human activity is reduced and remaining CO2 is balanced by an equivalent amount being removed. Although, in the case of China, state officials have said that “carbon neutrality by 2060” will include the reduction of other greenhouse gases too.

Carbon negative (Microsoft) – Becoming carbon negative requires a company, sector or country to remove more CO2 from the atmosphere than it emits.

Germany’s government estimates that in 2045, 97 percent of all emissions can be abated, so that a remaining three percent or ca. 35 million tonnes CO2 have to be somehow removed.

A first tentative way of the government to account for this was the move to include the carbon sinks of the land use, land use change and forestry sector (LULUCF) in the reformed Climate Action Law. This came after the European Union decided to include the LULUCF sector in its greenhouse gas budgeting as part of the "Fit for 55" push for more climate action to reach its 2030 emission reduction goals. The environment ministry set the targets at 25 million tonnes in 2030 and lets them increase to reach 40 million tonnes in 2045.

The unavoidable emissions of 2045

But while governments in other countries, such as the U.S., are encouraging the development of carbon removal technologies, and others such as Norway and Denmark are starting to market themselves as potential CO2 storage sites, many German politicians still lack enthusiasm when it comes to including negative emissions in the larger net-zero picture. “In addition to reducing CO2 emissions, methods will likely be needed to remove CO2 from the atmosphere,” wrote the conservative-led energy ministry in June 2021.

The Social Democrats (SPD), in government with the conservative CDU-CSU alliance for the past eight years, also remain sceptical. “I'm not entirely sure whether carbon capture and storage (CCS) might eventually need to play a role in reaching the goal of climate neutrality in 2045. But at the moment I don't see any room for it at all,” SPD energy expert Johann Saathoff told CLEW. His fellow SPD MP Nina Scheer told CLEW: “We have alternatives to underground storage by avoiding emissions; and CCS is associated with repository risks, such as subsequent leakage”.

CCS got off to a rocky start in Germany

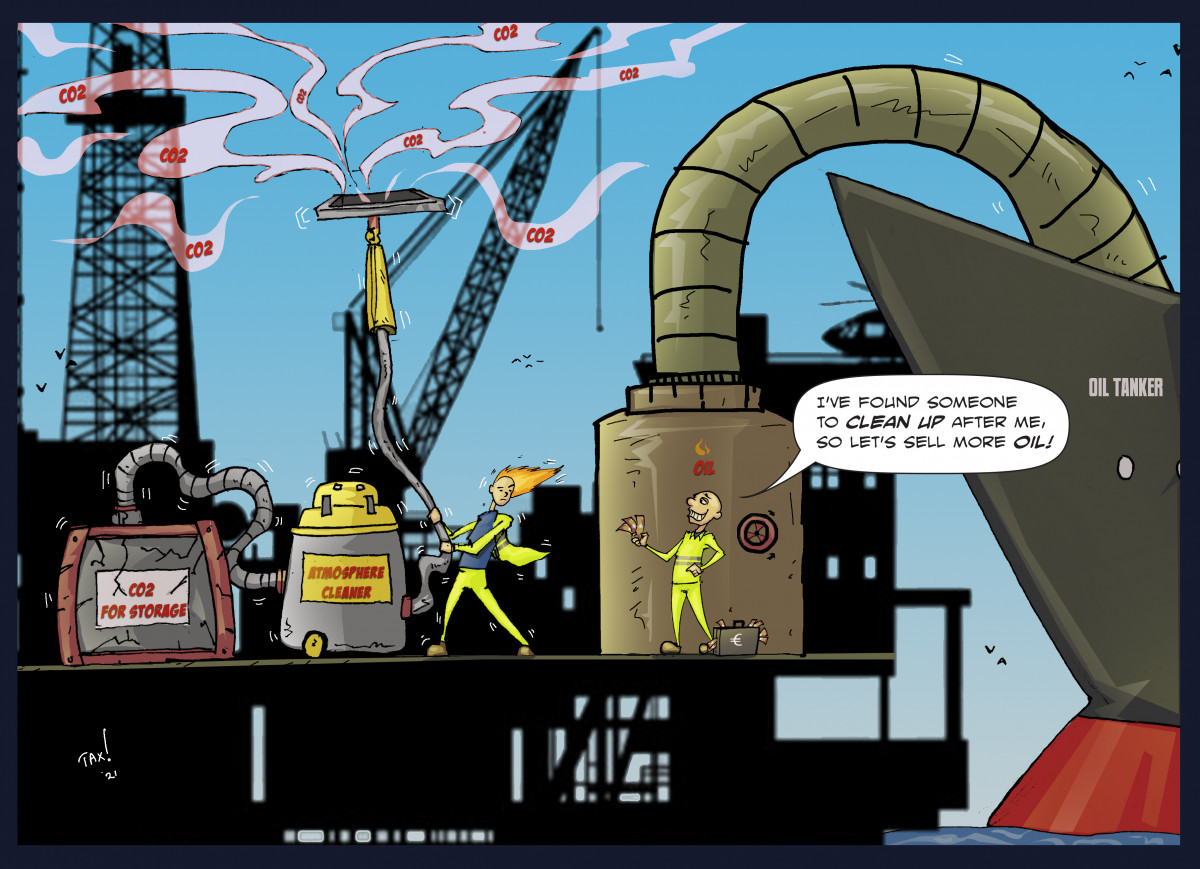

Their reluctance goes back over a decade, when carbon capture and storage or sequestration (CCS) was touted as a solution to catch and store the emissions that arise from fossil fuel usage in power generation and industry. Large oil companies in particular pushed the idea, and several governments were (or still are) ready to support “clean coal” by making existing and new coal-fired power stations “CCS-ready”. Fourteen years ago, the government of the city of Hamburg and coal plant operator Vattenfall were looking into equipping the newest addition to their coal-fleet “Moorburg” with CCS. The problem: CCS would not be used to capture and store unavoidable emissions, but to conveniently keep in place the existing fossil-fuel based energy system.

In Germany, environmental organisations such as Greenpeace made sure that this was not going to be an option. Their fierce campaigning discredited CCS. Citizens protested against “a final CO2 repository under their feet” which they also connected with their opposition to fracking, and made it “a toxic subject that decision makers would not touch for years”, researcher Schenuit remembers. As part of Germany's coal exit plan, the power station Moorburg was shut down after only five years in operation, and had never been equipped with carbon capture technology. CCS was as good as banned by legislation passed in 2011.

Today, with a coal exit plan in place, Greenpeace CCS expert Karsten Smid agrees that “clean coal” with CCS is not a threat in Germany anymore. Nevertheless, the environment organisation keeps up the fight against what it considers a “high risk technology”. Apart from it still being unknown if the storage of CO2 in rock formations and saline aquifers will be reliably permanent – many projects were unsuccessful or managed to store only little amounts of carbon – Smid questions the “unavoidable” label of certain industrial emissions. “Who says that these process emissions cannot be avoided by using other processes and, wherever possible, substitute cement and steel with other building materials or by recycling? Maybe we need a ferro-concrete exit law?”

A new dawn for carbon direct removal – in natural sinks

“I understand the political rationale of not focussing on carbon dioxide removal too much and emphasising the need to reduce emissions instead. Achieving a 90 percent or more greenhouse gas reduction is a big enough challenge,” Schenuit said. “However, we also need a debate and political initiatives targeting our residual emissions, otherwise achieving the net zero target is not plausible”.

As liberal and conservative voices are pushing the topic onto the agenda again, news of success in direct air capture of CO2 and first pilots of “carbon farming” to increase the CO2 uptake of soils are indeed fuelling a new debate. And while many politicians and environmentalists are still standing their ground on CCS refusal, most stakeholders including Greenpeace, have shown an interest in tackling the topic in a more differentiated way. “Carbon direct removal is more than CCS, environmental organisations are focussing on nature-based solutions when we speak of negative emissions,” Smid said.

The first step must be using the potential of existing natural sinks: the re-wetting of moorlands, and natural forest management, says Greenpeace, followed by increasing the carbon uptake of soils and afforestation.

But researchers from the Mercator Institute of Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC) who compared the potential of different carbon direct removal methods in Germany have highlighted several uncertainties when it comes to land-based CO2 uptake. Moorlands are currently greenhouse gas sources in Germany, so rewetting them would firstly be an emission avoidance measure. “Only the new formation of peat would represent a CO2 extraction, but this happens so slowly that we don’t consider it a near-term option for additional carbon uptake,” Sabine Fuss from the MCC said.

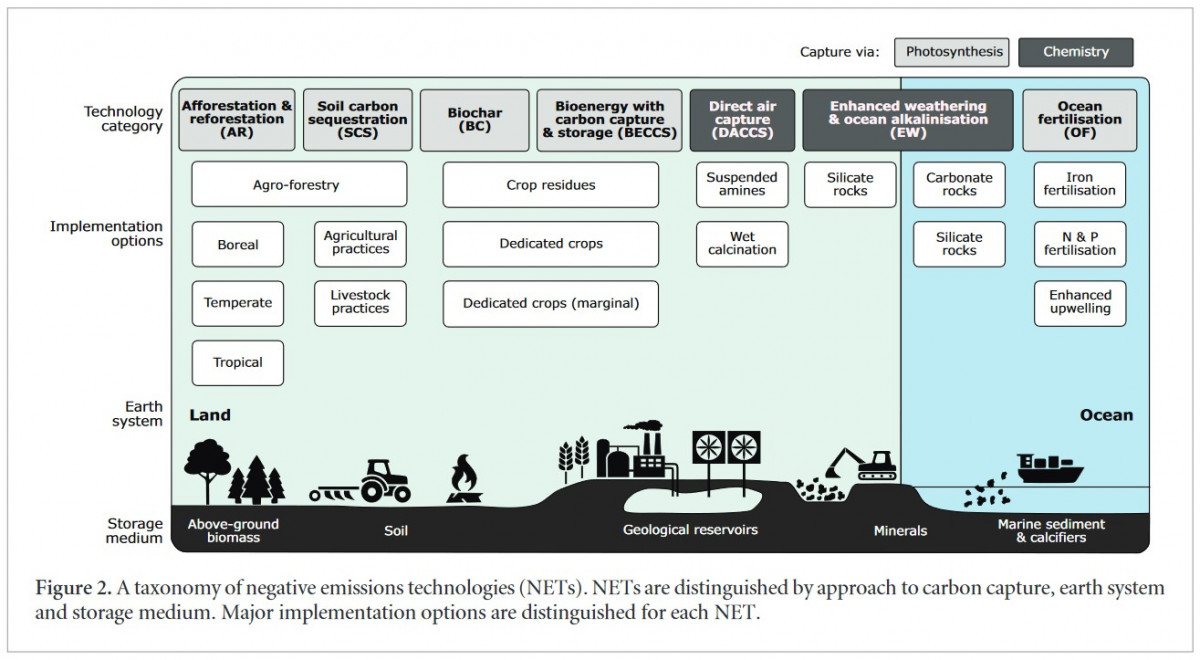

Negative emissions ABC: Afforestation - biochar - carbon farming - enhanced weathering

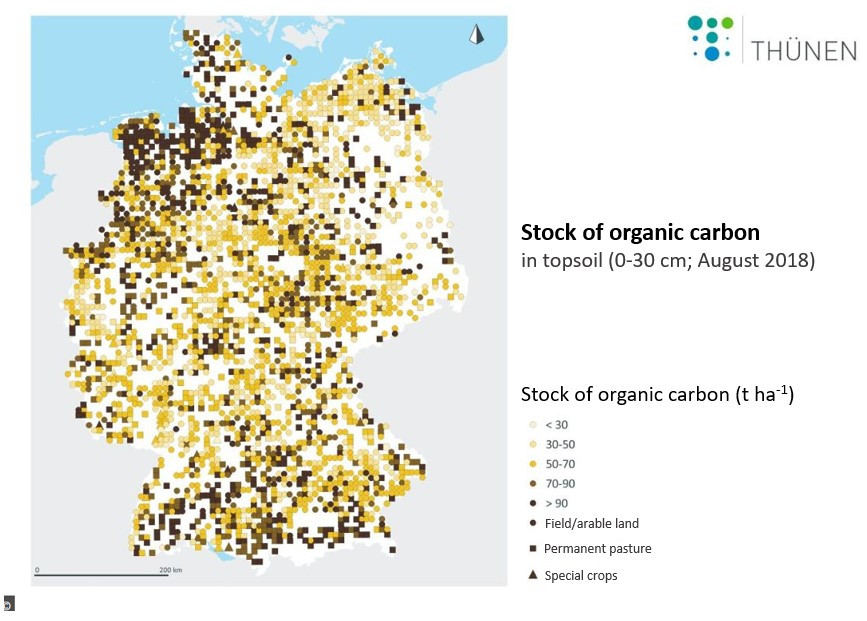

Another land-based option is using the ability of soils to store carbon through “carbon farming”. Reduced ploughing (low-till or no-till practices), planting perennial crops, cover crops and other methods, can help with humus build-up on fields, i.e. providing soil carbon sequestration. A 2018 comprehensive study of Germany’s soils’ organic carbon content came to the conclusion that a total of 2.5 billion tonnes of carbon is stored there in the form of humus, 1.3 billion t in fields and 1.2 billion t under grassland. However, projections also showed that these soils at the moment stand to lose carbon instead of taking up more, if not farmed with sequestration in mind.

Land-based carbon removal strategies face the issue of “saturation” and “permanence”. Soil sinks can only store certain amounts of carbon and the natural carbon storage in soils and biomass has the problem that it is reversible. Trees can burn or die from pests; soils - when hit by drought or treated differently by farmers - can emit their carbon content again.

The application of biochar (a kind of rich-in carbon coal made from converting biomass) into arable soils provides a more permanent carbon storage and has positive side effects for crop yields, but making biochar needs biomass resources and land. In “enhanced weathering”, small parts of minerals are distributed on soils to help bind CO2 from the air and sequester it in the ground; but the method has not been widely tested.

Large scale afforestation and growing vast amounts of biomass for use in bioenergy plants with carbon capture and storage technology (BECCS) have the drawback of using land that could otherwise be used for food production or more biodiverse habitats. And, in the latter case, underground storage would again be necessary, just like after carbon capture in industry.

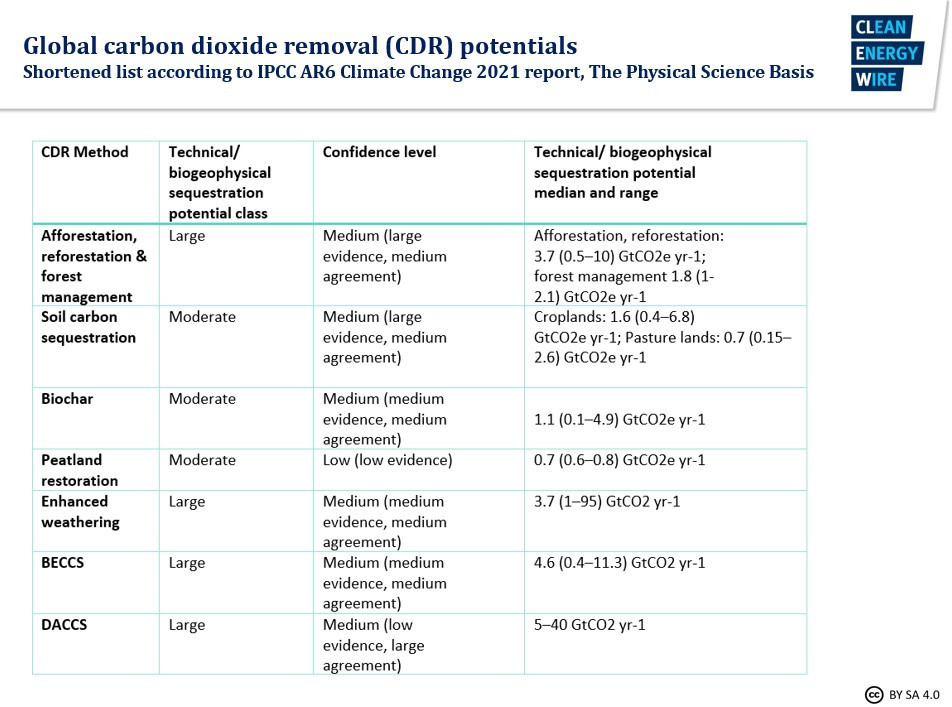

Infobox: Carbon direct removal potentials in Germany

Example estimates for removal potentials of different techniques in Germany per year, according to the MCC:

Bio energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS): 65-120 MtCO2 p.a. (limiting factor is biomass potential)

Direct air capture with storage (DACCS): 35-55 MtCO2 p.a. (limiting factor is energy demand)

Afforestation: 7 MtCO2 for (limiting factor is land area)

Plant carbon (biochar): 3-7 MtCO2 p.a. for (limiting factor is biomass potential)

Accelerated weathering: 30 MtCO2 p.a. for (limiting factor is total agricultural land)

Due to land competition, the total potential is less than the sum of the individual potentials.

So, are technological options such as direct air capture of CO2 (and storage) or capturing industry emissions directly at the plant the easier solution after all? The space in saline aquifers (porous and permeable rocks filled with salt water) under the German North Sea is large enough to store up to 20 billion tonnes of CO2 the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) says. Norwegian geologists say there is plenty of space available to store 70 billion tonnes of CO2, several decades worth of Europe’s industrial CO2 emissions, under the Norwegian continental shelf.

“Technologies to decarbonise ‘the last mile’ have to be planned now”

“We see it the other way around, as politicians tend to shy away from industrial approaches because of the storage problem, land-based approaches have their justification,” said Matthias Kalkuhl of the MCC. The natural sinks are also cheaper and they can be deployed at once, even if the problem of permanence remains, Fuss and Kalkuhl said.

In the longer term, however, think tank Agora Energiewende assumes in its projections that the potential of nature-based carbon removal in Germany is not big enough, lacks permanence, and that these sinks are already under pressure. They deem it more likely that the five percent residual emissions in 2045 will be compensated with technological means. Many industry associations, researchers and environmentalists, therefore, push for tackling the development and scaling of these methods here and now – despite their negative perception in society and politics.

“We will use these technologies to decarbonise ‘the last mile’, but this must be planned at the beginning of the journey,” Viviane Raddatz of WWF Germany said at an event held by the German Industry Federation (BDI). Avoiding emissions always has to be paramount over capturing and storing or using CO2, but technology development for decarbonising industry processes has to take place now and must not be delayed, she said.

“Natural sinks will not be enough,” said the head of the German Energy Agency (dena) Andreas Kuhlmann, when presenting a dena report on the necessary technology scale-up and infrastructure for technological carbon removal. This view is backed by research organisation acatech and industry association BDI and its CO2 intensive members from the cement sector. They are demanding that the next German government address the lack of infrastructure to transport CO2, the lack of planning security and funding for transformation of industries, and the problem of public acceptance for CO2 storage. “Two thirds of our emissions are process emissions, we absolutely need carbon capture, usage and storage,” Christoph Reißfelder, head of Heidelberg Cement liaison office in Berlin, said at the BDI event.

A market for farmed carbon and sucked up CO2?

With all carbon direct removal methods in their infancy, the challenge will be how to design the regulatory frameworks, which are necessary to monitor and incentivise their deployment. Direct air capture technology is hardly in use and expensive. Monitoring the carbon content of arable soils is laborious and error-prone. There is little long-term experience with carbon storage. How will it be handled – also with regard to insurance – when things go wrong and the CO2 from soils, forests, or underground geological storages escapes? And with all this in mind, how will these carbon removal methods grow to scale and how will this be financed?

Under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), farmers already receive money for measures that benefit biodiversity and healthy (carbon-rich) soils and pastures. Looking at the difficulties that measuring, monitoring and verifying nature-based CO2 extraction like carbon farming pose, some researchers and environmentalists like Smid at Greenpeace argue that it will be best to expand rewarding farming practices that are known to enhance soil organic carbon, rather than measuring, remunerating and trading each individual tonne of CO2 removal by thousands of farmers.

Nevertheless, some German farmers already dabble in the CO2 offset market, having joined pilot schemes by U.S. company Indigo and crispbread maker Wasa to create a system of different soil treatment that financially rewards the climate performance of farmers.

The European Commission has launched a carbon farming initiative and it is likely that current workings of the Commission will eventually result in some kind of market for emission withdrawals. The EU is funding carbon removal start-ups via its innovation fund. “We are looking at all the initiatives that are out there, land-based and technology approaches. We will learn from them. And, based on that experience, we will take it a step further to create a carbon removal legislation,” Christian Holzleitner, Head of Unit Land Use and Finance for Innovation, DG CLIMA, European Commission, said at a panel discussion. By the end of 2021, the Commission will present a strategy on the carbon cycle, including scenarios for markets with different removal options in mind, he said, adding that a more technical legislative proposal would follow “hopefully within this legislative period”.

Both the EU Commission and researchers stress that a water-tight certification standard for negative emissions, in particular ensuring their permanence, is of the essence if these are going to play a role in the carbon cycle. “We urgently need a definition of permanence. There is confusion in the political debate about how many years the carbon has to stay out of the atmosphere. That applies particularly to the land-based carbon removal strategies,” said Oliver Geden, Senior Fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

There are already a few examples where countries (e.g. New Zealand) have incorporated carbon dioxide removal into CO2 markets. “Regardless of how these markets function in detail, monitoring and verification is the key challenge,” researcher Schenuit said. If the necessary transparency and reliability is guaranteed, one tonne of removed carbon could be traded just like the permission to emit a tonne of CO2 is at the moment.

MCC researcher Kalkuhl says the price for CO2 removal should be based on the abatement costs for carbon emissions. What could start off with a separate target amount for negative emissions in the short term could result in a carbon removal trade system with a link to the existing EU ETs in the medium term and finally be merged with the ETS (“hard linking”) in the long term.

“If a carbon removal technology turns out not to be profitable in the long term, even when looking at CO2 prices of 300 euros, then this method should not be used”

“If a technology [such as direct air capture] then turns out not to be profitable in the long term, even when looking at CO2 prices of 300 euros, then this method should not be used,” argues Kalkuhl. He said in this market it would also be possible that it becomes cheaper to withdraw a tonne of carbon than to avoid its emission. Fuss added that, apart from “geophysically unavoidable emissions”, society could decide in the future to continue emitting CO2 for lifestyle reasons or because replacing certain emissions from flying or eating meat would simply be too cumbersome.

Stick to the “reduction first, removal last” hierarchy and split the targets

But this rings the alarm bells of everyone promoting a strict hierarchy of climate change mitigation approaches in Europe, as it also does whenever the idea of using CCS for fossilfuel-based and other abatable emissions is floated.

“The hierarchy that avoiding emissions comes first has to be implemented. Otherwise, we would be going into a direction that wouldn’t fit with long-term climate neutrality,” Frank Peter, Director Industry at Agora Energiewende, said.

Many researchers, including at Agora Energiewende, the SWP, and environmentalists from the WWF, therefore promote splitting targets for emission avoidance and emission removals. “A split target would be a way to make clear what role carbon dioxide removal really plays if, for example, there is the target of 90-95 percent emission abatement and 10-5 percent CO2 removal”, the SWP’s Geden said. This could also ward off the impression that companies can simply buy carbon emission offsets to become climate neutral, he added.

Industry representatives - be it Christoph Reißfelder of Heidelberg Cement, or Lisa Rebora, Senior Vice-President for Emerging and Future Business at Norwegian energy company and CCS pioneer Equinor - stress their commitment to the “abatement first” hierarchy. Even Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC) puts “reduce” in first position and “remove” at the end of its circular carbon economy model.

But in many countries, be it the oil or gas-dependent Middle East, Russia or the U.S. and Australia, large fossil fuel players are eyeing removal and storage technologies as key to making CO2 emissions fall without having to upset existing energy sources, material use, and revenue streams.

Meanwhile, countries and companies from all sectors are setting themselves climate neutrality targets, often without having a plan for 100 percent emissions abatement in place. Unsurprisingly, there are “very many interested parties” in Equinor’s Northern Lights CCSU development, which is co-owned by Shell and TotalEnergies. The project is scheduled to come online in a couple of years, Rebora said.

When launching the world’s first direct air capture with CCS plant in Iceland in the beginning of September 2021, Climeworks Co-CEO Christoph Gebald said: “Thirty years down the road this could be one of the largest industries on the planet.” Climeworks is already attracting individuals (8,000) and companies (Microsoft is involved, as well as Swiss Re and German car-brand Audi), who wish to reduce their carbon footprint by letting emissions be sucked out of the air. The state-of-the-art plant will capture 4,000 tonnes of CO2 per year.

Not only Iceland, where Climeworks partner Carbfix is “turning CO2 into stone”, but also Norway and Denmark are positioning themselves as possible CO2 storers for other European countries as they see a lot of potential for sequestration under the North Sea. Danish MEP Niels Fuglsang, a member of the ITRE Committee in the European Parliament, pointed out that in the future there would have to be whole new carbon transport infrastructure and value chain to enable a carbon cycle market.

Ball is in the court of the next German government

With the negative emissions debate between researchers, industry and environmentalists in full swing and the European Commission preparing its green paper, it is now for European member states and, in Germany, for the new government after the September elections to put in place targets, regulations and incentives to initiate carbon removal at scale.

Some large scale CDR research projects funded by the science ministry are underway, but a long expected stakeholder dialogue announced by the federal energy ministry (BMWi) in Berlin on CCS never materialised under the current government. And while the free liberals (FDP) are pushing the subject of negative emissions wherever they can, both SPD and the high-polling Green Party – who are likely to be part of the next government - remain doubtful as ever. “I don't think a discussion about whether we can store CO2 in Denmark or Norway will help us at present," Green Party MP Lisa Badum told CLEW. "We have to put the focus on cutting emissions now and discussions about CCS are a distraction. They also involve the danger of people saying ‘well, we're not in a hurry to cut emissions because we can just store CO2 below the North Sea later’. It's a chimera – a solution that doesn't exist today.”

MCC researchers Fuss and Kalkuhl conclude: “It is clear that the current state of affairs does not allow a focus on a single ‘winning technology’. On the contrary, everything points to the need to find an appropriate carbon direct removal mix that can remove as much CO2 as is deemed necessary while minimising the technical, economic, social, and environmental risks of scaling up”.