Climate dominates Germany’s most unpredictable election in decades

Sixteen years of Angela Merkel as chancellor of Germany draw to a close when the country is heading to the ballots on 26 September. The planned retirement of the longest-ruling head of government in the European Union has not only led to concerns over the power void that the crisis-tested Merkel might leave in international diplomacy. The still widely popular conservative politician’s parting has also led to the unprecedented situation for domestic German politics that an acting chancellor is not running for office again. In a historic first, this prepared the ground for a head-to-head race between three different parties and their chancellor candidates. Ending over 70 years of bipartisan dominance by the conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the Social Democrats (SPD), the Green Party established itself as a third leading force, a shift in the balance of power that could mean the country would also see the formation of its first tripartite government coalition since the 1950s.

The Greens’ rise in popularity has been fuelled by quickly growing concerns over the impact of climate change and the country’s response to it, which despite one and a half years of a deeply troubling pandemic has emerged as a yardstick for the election choice of many voters. Since the last election in 2017, Germany - much like the rest of the world - has seen weather extremes increase in frequency and intensity. Severe droughts in 2018 and 2019 gave rise to mass protests led by the Fridays for Future movement, which brought hundreds of thousands of especially younger people to the streets. Deadly floods hitting large parts of western central Europe in July, which killed almost 200 people in Germany alone and were largely attributed to global warming, then put climate firmly at the centre of attention again and ensured that it topped the list of voters’ concerns.

Environmental groups, researchers and media commentators therefore were quick to brand the 2021 vote as a “climate election.” And for sociologist Bernd Sommer, whose research at the University of Flensburg focuses on the social reception of climate policies, the label is still deserved as the campaign enters its final week. According to Sommer, this is due to two reasons: “First, it’s clear that climate action and other environmental issues have greatly gained in importance for voters in the past years,” he told Clean Energy Wire. “Of course, this doesn’t mean that everyone will make their vote depend on it. But parties definitely had to acknowledge the fact that many people consider climate policy in their electoral choice.”

Together with tighter climate targets by the EU, the climate protests instilled a slew of initiatives in the government coalition of the CDU/CSU and the SPD. Measures that supporters of more rigorous emissions reduction had been advocating for years, such as a climate action law, resolute e-car support, national carbon pricing or setting a date for the end of coal power were announced just before the coronavirus crisis confounded the political agenda. But the package still failed to convince climate researchers and activists alike and a landmark court ruling in spring forced the government to step up its efforts and bring forward the target year for complete climate neutrality by five years to 2045.

2030 climate target already moving out of reach - and all parties lack a solution

Yet, a government draft report emerging shortly before the election found that the country is far from being on track to this goal and likely to widely miss its tightened 2030 emissions reduction target if no additional action is taken, leaving a final blemish on Merkel’s mixed climate legacy. For researcher Sommer, this is where the second dimension of the ‘climate election’ comes in. “This has less to do with voters and more with the physics of climate change. The next government will arguably decide whether or not Germany can still fulfil its agreed contribution to limiting global warming in line with the Paris Climate Agreement.”

With emissions going up again at the fastest rate in decades in 2021 after the dip in economic activity caused by the coronavirus, conditions for a new government to succeed in this endeavour are far from ideal. To make things worse, an analysis of party election programmes by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) published in early September found that none of them – including the Greens – has a coherent concept to ensure the country abides by its own emissions reduction targets, with slow renewable power expansion and too low carbon prices being major stumbling blocks.

For think tank Agora Energiewende, this leaves only one conclusion: “The next government has to introduce the most ambitious climate action programme Germany has ever seen within the first 100 days.” The new climate targets could only be achieved if action is taken right at the beginning of the next legislative period – and if investments in clean technology and other measures are increased threefold also in the long run. “No matter who forms the next government, they will have to initiate a wave of investments – or risk failing the targets,” Agora Energiewende head Patrick Graichen said.

The think tank is not alone in demanding more efforts by the new administration: Industry groups, labour unions and environmental groups have all urged the next government to tackle key challenges of the climate-friendly transformation, with a focus on more renewables, building efficiency, green hydrogen and deep changes in the transport and the country’s vast industry sector.

"Jamaica", "Traffic Light", "R2G" - colorful coalition options promise long negotiations

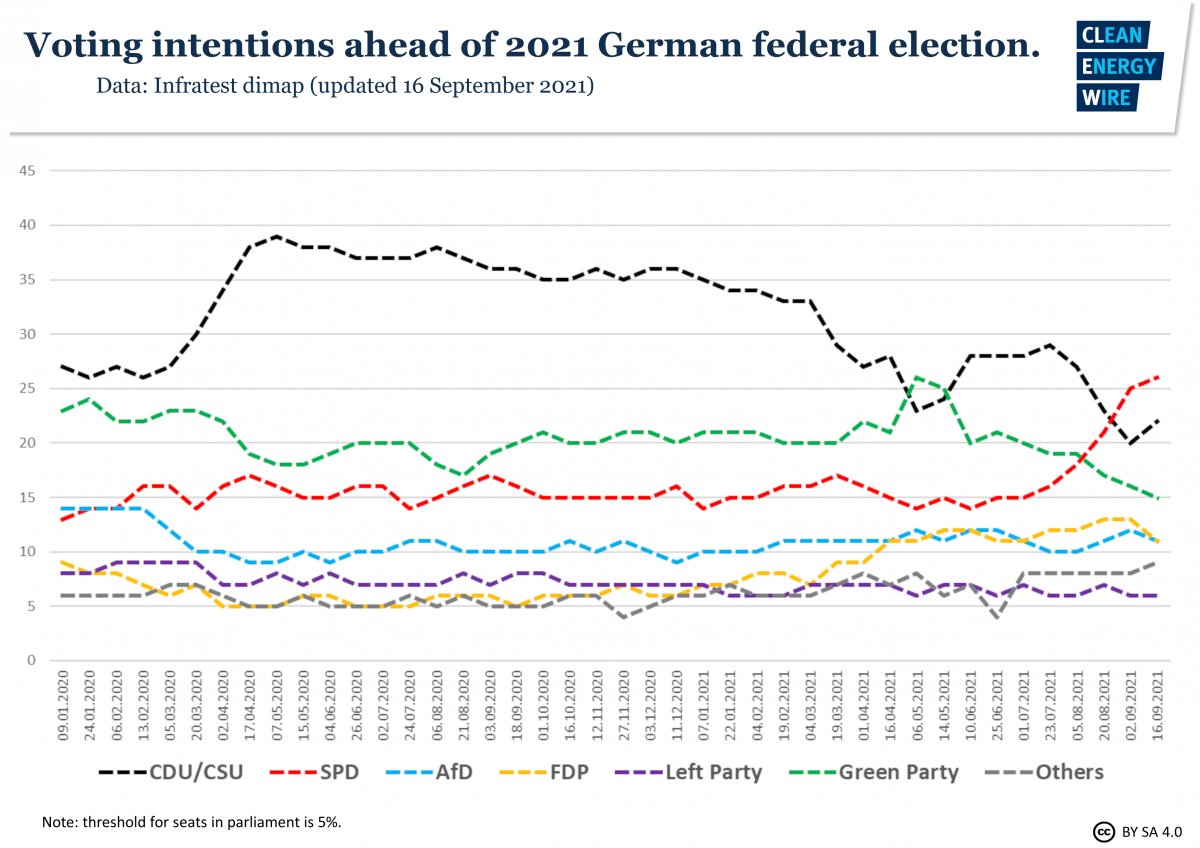

But just who will be sitting in a new government remains all but uncertain one week before the ballot. Both the SPD’s candidate Olaf Scholz and the CDU/CSU’s contender Armin Laschet can hope to come out first. This is great news for Scholz, who polled as a distant third only three months ago and now has topped popularity rankings for weeks - and a veritable disaster for Laschet, whose conservatives saw an unprecedented collapse of voter support since he was announced as their top candidate after a long internal party battle. The prospects for the Greens’ Annalena Baerbock to become chancellor have largely waned since her party’s stint at the top of polls earlier this year. But the Greens still can hope to vastly improve their result and gain twice as many seats as in the last election, so that forming a government without them will be difficult.

The three larger parties are trailed by the pro-business FDP, the Left Party and the far-right AfD, the only party without any credible option to enter into a government coalition. This still leaves room for a whole range of other combinations, of which “Jamaica” (CDU/CSU, Greens, FDP) “Traffic Light” (SPD, Greens, FDP) or “R2G” (SPD, Greens, Left Party), all referring to the parties’ colours, are only three conceivable options. As a result, the range of possible approaches to implementing Germany’s climate targets is vast – even if all parties have assured to strive for the more ambitious Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

But with highly controversial issues at stake in climate and energy policy alone – for example a possible end date for combustion engines – coalition negotiations in any combination look set to become tedious. The ill-fated “Jamaica” coalition talks in 2017 dragged on for months before collapsing, with the result that the “grand coalition” between the conservatives and the SPD eventually continued to govern half a year after the votes were cast.

And even if a “grand coalition” should receive enough votes to stay in power also this time, which according to the polls it will not, most voters and also leading coalition figures agree it has reached its best-before date. This means Germany – and by implication to some extent also Europe – is in for protracted coalition negotiations in the continent’s biggest economy until the parties agree on a coalition contract.

This could take months on end, meaning Angela Merkel might enter into 2022 as a “lame duck” chancellor, a delay that the country can hardly afford if the 2030 target is still to be brought into reach. Several NGOs and politicians have already stressed that the new German government's active support will be essential for leading key EU projects like the Green Deal or its "Fit for 55" climate package to success - and criticised that the European context received little attention in the candidates' campaings.

"The truth" about climate action costs - a challenge for the next government

For sociologist Sommer, however, the really tough negotiations will only begin once a new government has started its work. “A new government will have a hard time continuing in the same vein as the previous ones and keep individual citizens largely out of climate action and the energy transition. It will affect peoples’ lives,” Sommer said.

For him, this also explains why, despite the pledges to curb global warming, no party’s election programme really spells out what it takes to fulfil the Paris Agreement. “No party currently dares to really speak about the actual consequences for the everyday life of citizens. Instead, it appears they back the goal to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius but at the same time claim that everything just can stay more or less the same.” Sommer's assessment is supported by an appeal made by Wolfgang Schäuble, former conservative finance minister and now president of Germany's parliament, the Bundestag. In August, Schäuble called on politicians to be more honest to voters regarding the costs of climate action, arguing people deserve to know "the truth" about what lies ahead.

Schäuble's statement ended with the optimistic prediction that voters will be able to cope with the demands of deeper emissions reduction. But Sommer's research has shown that this might not always be the case. Surveys suggest that support for climate action is shrinking rapidly as soon as it is made conditional on certain policies, for example if energy prices should rise, the sociologist said. “People generally agree on the common goal of climate action but disagree on its consequences.” While Merkel’s outgoing government at least achieved that the goal is now legally fixed, a successor that eventually will emerge after 26 September is going to be left with the difficult job out of translating this into reality.