Many ways to climate neutrality: Who are the candidates running to succeed Merkel?

Germans will head to the polls on 26 September to choose their next government and determine a successor to Angela Merkel, who is leaving the Chancellery after 16 years in office. The country has firmly set sails for climate neutrality by 2045 and the next leader will have to pursue that legally binding goal - but the election outcome could prove critical for the speed of the energy transition in this decade.

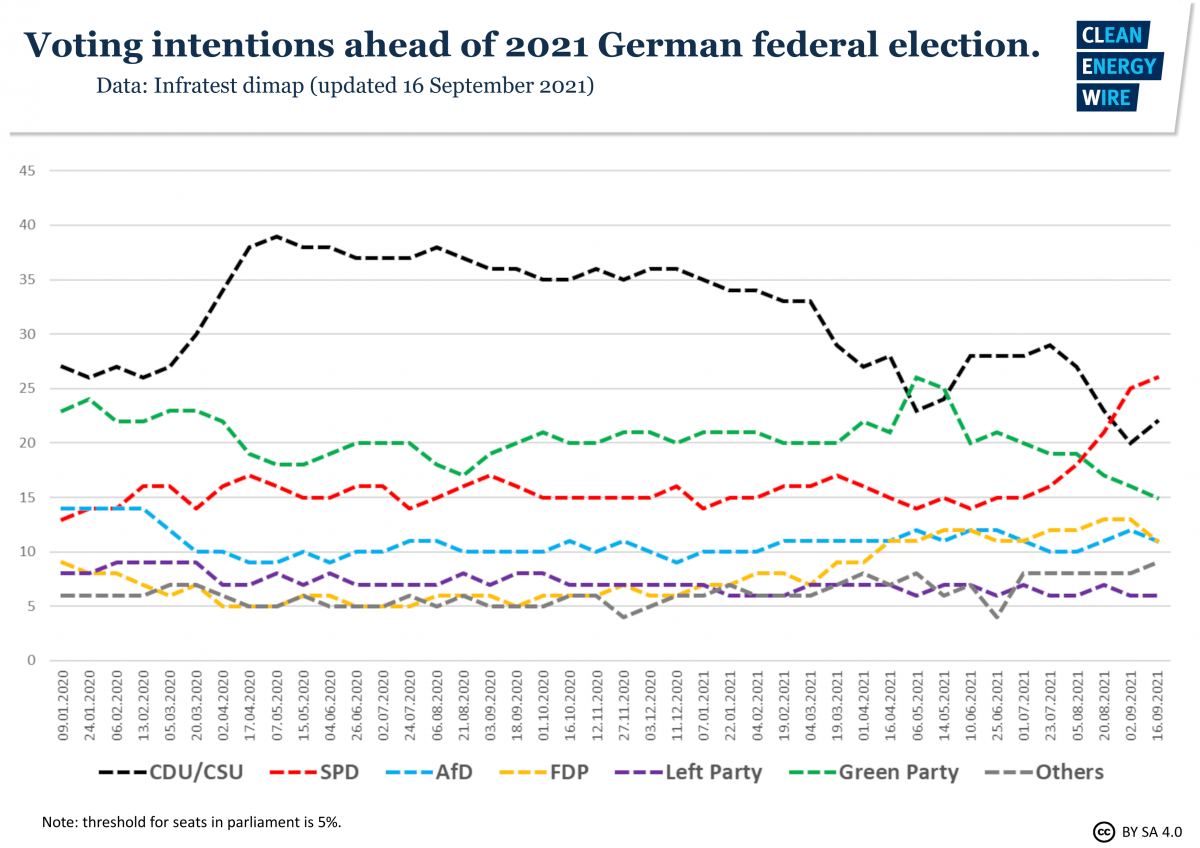

The vote is described as the country's "most volatile and unpredictable federal election in recent memory," because the three candidates' parties remain neck-and-neck in opinion polls: Armin Laschet's and Merkel's conservative CDU/CSU bloc, Olaf Scholz' Social Democrats (SPD) and Annalena Baerbock's Green Party.

Germany is traditionally governed by a coalition, because no single party gets an absolute majority in the elections – it is currently led by a conservative-SPD alliance. But surveys indicate the country will get its first federal government coalition made up of three political camps since the 1950s, because none of the three largest parties has managed to build up a convincing lead.

As a result, voters face a confusing array of possible coalitions. Many Germans remain undecided, which adds to the uncertainty. The prospect of a three-way coalition also indicates arduous and drawn-out negotiations that can take many months before a new government is formed. Until then, the incumbent government will continue to carry out the official duties as a caretaker. Germans elect their parliament, which then choses the chancellor once the coalition is agreed.

Despite this election's unpredictability, the outgoing Merkel government's path on fighting climate change and other issues is unlikely to be radically altered. This is because compared to many other countries, all major parties advocate fairly similar policies in Germany's consensus-based political system. Merkel's continued popularity also indicates that most voters hope for continuity in style and substance.

Following unprecedented catastrophic floods, heatwaves and droughts in Germany, which were widely seen as connected to rising temperatures and have spurred massive climate protests led by the Fridays for Future movement, the fight against climate change is a top concern for German voters.

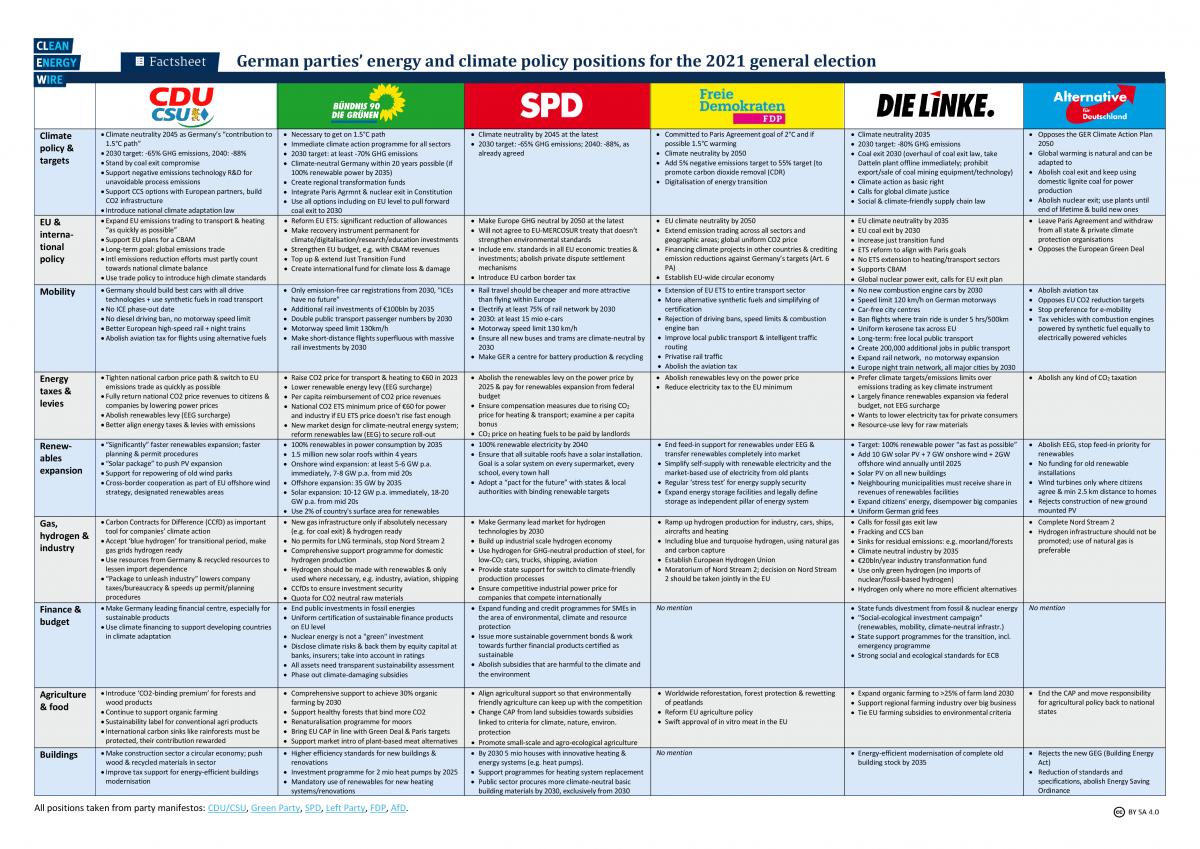

All three candidates say they are firmly committed to making the country climate-neutral by 2045, the official government target. Still, the vote will determine the pace and scope of climate policy and the country's landmark energy transition in the years to come, as a closer look at the candidates reveals significant differences in approach.

Olaf Scholz - Social Democratic Party (SPD)

German finance minister and vice chancellor Scholz has become the clear favourite to succeed Angela Merkel on the final stretch of the election campaign. If Germans could elect the country’s next chancellor directly, more than 40 percent would choose Scholz, compared to less than 20 percent for the conservatives' Laschet and the Greens’ Baerbock.

Many voters believe the 63-year-old Scholz, who served as employment minister in a previous Merkel cabinet, best embodies her cherished virtues of caution and stability. The former mayor of Germany's second city Hamburg is widely described as robotic and uncharismatic, which earned him the unflattering nickname "Scholz-o-mat." But most voters credit him for a solid record as finance minister, where he calmly oversaw Germany's massive funding package to help businesses and workers during the pandemic and also the introduction of a sustainable finance strategy meant to better align this key sector with overall climate policy.

Scholz has otherwise not yet made a name for himself in energy and climate policy, but he has promised an "immediate fresh start" after the elections and called for a focus on renewables expansion, including a new law to ensure industry has enough renewable electricity to decarbonise over the coming decades. "As chancellor, I will ensure we pick up speed in the first year," Scholz said last month, adding he plans to accelerate approval procedures for wind turbines and other investments.

His party's election programme also puts great emphasis on climate action as the "challenge of the century." The SPD says it will support controversial climate action measures like a general speed limit on German motorways, an idea that has so far been considered a no-go for most politicians and was mainly pushed by the Green Party. The SPD does not rule out pulling forward Germany's coal phase-out from the current target year of 2038. It emphasises that climate protection measures must be socially just and should also promote the economy. "For the SPD, climate protection is an industrial project, not a re-education course," Scholz said, suggesting voters will not have to face massive behavioural changes.

But environmentalists question Scholz's true climate convictions. He has repeatedly ranked industry concerns higher than environmental issues, and suggested that Germany should stick to its existing timetable for phasing out coal instead of openly calling for a faster exit - although he later watered down his stance, stressing 2038 would obviously be the latest possible date. "We have made clear agreements that are important for the companies, for the workers and also for the region. And these agreements apply and should be respected," Scholz said during a campaign stop in East Germany's coal mining region. According to climate scientists, Germany will need to phase out coal by 2030 at the latest to achieve its climate targets.

Scholz also rejected the Green Party’s proposal to increase the price of CO2 emissions from transport faster than currently planned to protect the climate. "Those who now simply keep turning the fuel price screw show how little they care about the needs of the citizens," Scholz said.

Armin Laschet - conservatives (CDU/CSU)

Laschet started out as the heir apparent to fellow conservative Merkel, but his party has plummeted in the polls following a lobbying scandal involving several MPs, accusations of mishandling the fight against the coronavirus pandemic and Laschet's clumsy reaction to the deadly floods in July.

The 60-year-old premier of Germany's most populous federal state, the traditional industry and coal mining heartland North Rhine-Westphalia, is seen as a Merkel loyalist and also stands for continuity with her centrist course.

But the uncharismatic Laschet struggles to motivate the base of his party. He faces the double challenge of keeping former Merkel voters on board while at the same time quelling an internal power struggle over the conservatives' party identity. His bid for chancellor had been preceded by infighting with his CDU/CSU rivals Friedrich Merz, a conservative CDU hardliner who challenged him as party leader and Markus Söder, Bavarian state premier for the sister party CSU, who has only reluctantly supported Laschet's candidacy after losing out in the conservative alliance's contest for picking the top candidate.

Even though Laschet has been an ardent supporter of Germany's planned transition to a hydrogen-based economy, his reputation in climate policy is dominated by pro-industry positioning in the country's coal exit negotiations, and his regional government's heavy-handed eviction of a camp of environmental activists opposed to the expansion of a coal mine, which was carried out under a false pretext and violated the law, according to a recent court ruling.

Laschet – who has invoked his father’s job as a coal miner to emphasise his working-class background and dependability – is also criticised for his generous stance on granting coal companies comfortable compensation payments and his defence of a newly opened coal plant. He has warned against curtailing Germany's economic opportunities through "excessive" climate action that would scare industrial companies away with high power prices and tight regulation.

Annalena Baerbock - Green Party

Baerbock is her party's first-ever candidate for chancellorship, but after a brief spike in voter approval, which saw the Greens temporarily lead in the polls earlier this year, the party has fallen behind Scholz's Social Democrats and Laschet's conservatives. Baerbock apologised for mistakes that were at least partly to blame for the drop in her party's popularity: She had to adjust her public curriculum vitae several times and had failed to directly declare some payments from her party in her role as its leader.

But even if they do not win the elections, polls currently indicate that it is likely the Greens will form part of Germany's future government. The party has shed past radicalism to become centrist, and it has already been part of a federal government between 1998 and 2005.

Baerbock is a 40-year-old career politician with a reputation for prudence and diligence, but without any government experience. As a climate expert and member of parliament for the eastern German coal state of Brandenburg, she gained recognition during Germany's coal exit negotiations. In contrast to her competitors, she is often described as "media-savvy and charismatic."

In her nomination speech as the only female candidate to succeed Merkel, Baerbock said she wanted to make climate action "the yardstick for all sectors" in order to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement. "Climate action is the task of our time, the task of my generation."

The Greens’ election programme is the most ambitious on climate among the major parties. It calls for 100 percent renewables in power consumption by 2035, a coal exit by 2030 and a ban on the sale of new cars that emit CO2 by that year. The Greens have also proposed a climate ministry with the power to veto other ministries.

However, Germany's climate movement, which includes the student protest movement Fridays for Future, accuses the Greens of not doing enough to reach the target of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.