German election primer – Parties split on raising national CO2 price

What role does CO2 pricing play in the election campaign?

What role does CO2 pricing play in the election campaign?

- Climate action is one of the core issues in the German election campaign, and carbon pricing on transport and heating fuels has emerged as a key point of public debate. It influences the day-to-day lives of voters, and particularly lower income households who must set aside a larger share of their available monthly budget for essentials such as petrol and heating.

- The possible need to increase the price for carbon emissions from transport and heating fuels – which took effect on 1 January 2021 – became a renewed hot topic in Germany’s political debates following the landmark constitutional court verdict that Germany’s climate plans are insufficient, and the subsequent decision by the government coalition to increase climate targets. Many lawmakers have said that the price will need to increase faster to reach new targets.

- The debate, however, had already been smouldering for some time. Ever since EU member state governments agreed to increase the bloc’s 2030 greenhouse gas reduction target at the end of 2020, it was clear that Germany would also need to do more. Conservative MPs called for a more ambitious national carbon price, as did the Green Party in its election manifesto draft from March 2021. Tabloid Bild Zeitung picked up on this manifesto demand in an interview with freshly chosen Green Party chancellor candidate Annalena Baerbock, catapulting the perennial German petrol price debate to the centre of the election campaign.

- In addition, the government coalition of conservative CDU/CSU and Social Democrats (SPD) had a dispute over the question of how the price on heating fuels should be split between tenants and landlords. Both debates made social fairness a key issue in the election campaign.

Why is the carbon price on transport and heating fuels such a controversial topic in Germany?

Why is the carbon price on transport and heating fuels such a controversial topic in Germany?

- Carbon pricing has long been a topic for expert discussions and, through the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), was largely reserved to policy or business stakeholder circles in certain sectors such as energy and industry. However, with the introduction of the national CO2 price on transport and heating fuels at the beginning of 2021, the issue has become more tangible for the majority of German voters. It affects the prices of everyday goods such as petrol and diesel or heating oil and natural gas.

- Customers often have limited options for reducing their use of these fuels, and it can be hard to change behaviour overnight. A commuter in rural areas still has to get to work, might not have the means to switch to an electric car and may have few public transport alternatives. Add to that a low income, and the carbon price really makes a dent in the available budget. That is why making it socially fair is the key challenge of the carbon price.

- It is a big deal. With almost 50 million registered passenger cars for 83 million people living in the country, the petrol or diesel price is a hot potato issue in car-fixated Germany. Some citizens drive several kilometres further to save a few cents per litre at a cheaper service station, and there are websites to help find the cheapest price on any given day.

Key campaign disputes so far

Key campaign disputes so far

- Higher petrol and diesel prices: A little more than a month after Baerbock was announced as the Green Party chancellor candidate, German tabloid Bild Zeitung pressed her on her party’s plan to increase the carbon price faster than currently planned, which would translate into 16 cents more per litre of diesel by 2023. Under the existing CO2 price system, this amount would be reached 2-3 years later. A fierce campaign dispute followed, as well as a debate about the social fairness of the carbon price. SPD chancellor candidate Olaf Scholz told Bild: “Those who now simply keep turning the fuel price screw show how little they care about the hardships of the citizens.” Left Party politicians such as Sahra Wagenknecht criticised higher petrol prices. She called it “socially unfair and poor alibi policy” and said the rich will hardly notice, while low-income households in rural areas might have no alternative to using their cars.

- Splitting the CO2 price costs between tenants and landlords: An agreement by the government coalition to split the extra costs from Germany’s new carbon price on heating fuels 50:50 between landlords and tenants failed at the last moment in June because the conservative CDU/CSU bloc vetoed it, arguing that landlords had no influence on tenants’ heating usage. Still, chancellor candidate Armin Laschet said landlords would not be let off the hook entirely. The SPD had called for the 50:50 split, because tenants cannot influence when and how landlords modernise buildings to make them more energy-efficient. Until the question is tackled again by the next government, tenants must shoulder the full costs.

- How to use CO2 price revenues: Introducing a carbon price means additional revenues for state coffers (the government expects about 40 billion euros in 2021-2024). To relieve citizens and businesses and help steer them towards more climate-friendly behaviour, the current grand coalition has decided to use part of the revenues to lower the renewables surcharge for power consumers (EEG surcharge), as well as other relief measures for citizens and industry and for climate action support programmes. Several parties want to pay back revenues as per capita payments to citizens (see plans below).

Why does the government have to adapt the price?

Why does the government have to adapt the price?

- Germany introduced a national emissions trading system for transport and heating fuels, a ‘cap and trade’ system in which the federal government sets an annual total emissions limit. However, during an initial phase the price will not be decided by market forces. There will be a fixed price at which emission allowances are simply sold to companies (2021-2025). This price is laid down in the legislation and can be changed by a parliamentary majority. Germany’s next government can make a proposal to reform the law.

A European debate

A European debate

- Germany certainly isn’t the only country to deal with heated debates on CO2 pricing and its effect on fuel prices. A green tax on fossil fuels in France which would have increased the price of petrol sparked the yellow vest protests in 2018.

- The European Commission on 14 July 2021 proposed the introduction of an upstream EU-wide emissions trading system for transport and buildings which would be operational from 2025, with a cap on emissions set from 2026. This has already ignited debates across the continent about the fairness of such a system within and between member states. At a meeting in July, EU environment ministers expressed “quite a lot of reservations” (see tweets from Pascal Canfin, chair of the environment committee of the European Parliament below). Fossil fuel reliant countries such as Poland would be hit much harder. Polish climate and environment undersecretary of state Adam Guibourgé-Czetwertynski warned that the Commission seemed “to be making the choice of taxing poorer households”.

What the parties want

What the parties want

- CDU/CSU: The conservatives want to “tighten the rising CO2 price path” and merge it with an EU system as soon as possible. The parties provide no details on dates and price levels. They aim to “fully return” carbon price revenues to citizens and businesses through lowering power prices. “The first thing we do is abolish the EEG levy,” says the manifesto.

- Green Party: The Greens want to “continue to improve the steering effect of the carbon price in a socially fair way” and raise it to 60 euros by 2023. They aim to use the CO2 price revenues to lower the renewables levy and introduce a per capita reimbursement (“Energiegeld”). To help commuters on low incomes, the Greens plan a climate bonus fund to support the switch to public transport or an emissions-free car. The Greens say that the CO2 price on heating has a steering effect “if the people who make the climate investments pay for it: the homeowners.”

- SPD: The SPD aims to stick to the current CO2 price path, arguing that industry and citizens must be able to rely on the agreed slow increase. The party also wants to use revenues from the CO2 price to lower the renewables levy and eventually abolish it by 2025, and it wants to “examine” a per capita bonus. For the carbon price on heating fuels, the SPD wants to “create legal provisions so that the CO2 price is covered by the landlords” – at least to the extent that tenants do not pay more for modernisation efforts than these help them save on energy costs.

- FDP: The pro-business FDP would ideally like to see a market-driven CO2 price as soon as possible in all sectors and across the world. It does not mention changing the existing price path for the national carbon price. The party aims to use revenues from emissions trading to finance existing renewables support, while ending the support in general – and abolishing the renewables levy. It also aims to use them to lower the electricity tax and introduce an annual per capita “climate dividend” for citizens.

- Left Party: The Left puts a high emphasis on a socially just energy transition that does not overly burden low-income households. The manifesto does not mention changing the carbon price, but the Left says it prefers targets and limits over emissions trading, and individual MPs have said they oppose raising the “current, socially unjust CO2 price”. The Left Party says that the CO2 price must not be added to the rent.It opposes extending EU emissions trading to transport and heating.

- AfD: The far-right populist AfD wants to abolish all taxing of CO2.

What are Germany's climate targets for the transport and heating sectors?

What are Germany's climate targets for the transport and heating sectors?

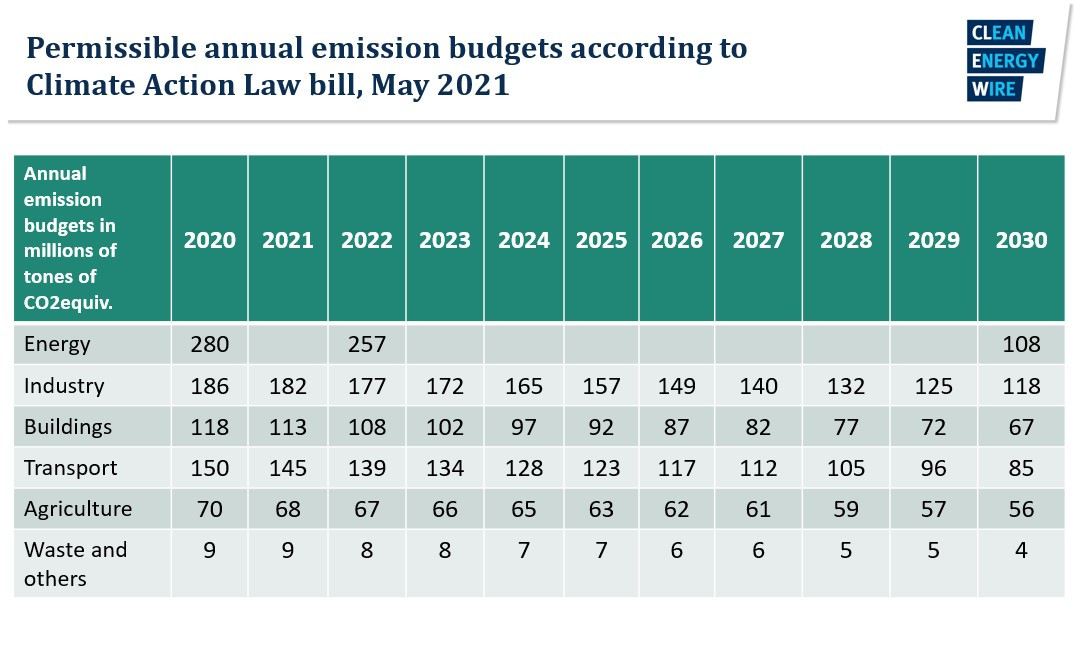

- Germany has brought forward its target date for reaching climate neutrality to 2045 and has set annual emission targets for each sector to reach that goal. Emissions in the transport sector will need to drop by more than 40 percent within this decade (see graph), with increasingly steep reductions towards the end of the 2020s.

- The buildings sector will also need to reduce emissions by more than 40 percent. Nearly two thirds of German homes still heat with fossil fuels and most of them also need to be modernised to lower energy demand.

What's the state of play in Germany's shift to low-emission heating and transport?

What's the state of play in Germany's shift to low-emission heating and transport?

- Germany has been struggling to lower emissions in the transport sector, which have remained broadly the same for decades as gains from more efficient engines have been eaten up by heavier cars.

- The CO2 price is meant to give low or zero-emission vehicles an extra push, but it is unclear what price levels are necessary to actually make a difference. The spread of electric vehicles has been slow in comparison to many other markets, but thanks to government incentives, registrations have picked up sharply since last year. Currently, more than one in ten new cars is fully electric. Germany crossed the threshold of having one million electric cars on its roads in July 2021, around half a year later than originally planned.

- The government aims to have a nearly climate-neutral building stock by 2050, according to its 2015 energy efficiency strategy. With new climate targets, it will almost certainly have to speed up the transformation. At the moment, only one percent of buildings are modernised each year, a rate much too low to reach climate targets. Emissions in the buildings sector have remained largely unchanged for nearly a decade, and it was the only sector not to reach its greenhouse gas reduction target in 2020 – resulting in a proposed emergency programme by the government. Residential buildings are responsible for about two thirds of final energy consumption in the building sector and they are an especially hard nut to crack, as homeowners must make significant investments for energy-efficient modernisation. The government is working to extend the energy transition to buildings with a ban on new oil-fired heating and tax incentives for renovations and low-emission technologies.

What has the outgoing government achieved?

What has the outgoing government achieved?

- The government is credited with kick-starting the recent rapid take-up of electric vehicles with generous subsidies. It has also taken up the challenge of establishing the charging infrastructure needed for a fast rollout of electric cars.

- But climate activists say the transport ministry often puts the brakes on the shift to zero-emission mobility instead of boosting it, mainly in response to car industry pressure. Ministry head Andreas Scheuer from the CSU, the Bavarian sister party of Merkel's CDU, is often labelled as a "minister of the car lobby" by the Greens and activists.

- The German government in 2017 failed to agree on a building energy law which would have set new standards for efficiency in buildings from 2019. The renewed coalition of CDU/CSU and SPD then passed the law in 2020, but refrained from introducing new energy efficiency standards for new buildings and renovations to “avoid rising rents”. These standards will be re-evaluated by 2023. However, the law contains some provisions to help get oil heating out of German buildings.

- The government also failed to set up a buildings commission similar to the coal exit commission tasked with negotiating possible measures for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the building sector.

- The NGO Environmental Action Germany in 2019 compiled a "chronology of failures" in the sector, starting from 2008.

All texts created by the Clean Energy Wire are available under a

“Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC BY 4.0)”

.

They can be copied, shared and made publicly accessible by users so long as they give appropriate credit, provide a

link to the license, and indicate if changes were made.

Graph shows parties' positions on reforming GErman energy taxes and levies 2021 election. Source: CLEW 2021.](https://www.cleanenergywire.org/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/2021-party-programmes-grid-taxes-levies.jpg?itok=_S2gCUNB)