German election primer: Candidates handle agriculture transformation with kid gloves

What role does agriculture and climate play in the election campaign?

Climate change and energy transition policy is possibly playing its biggest ever role in a German general election campaign – despite the Covid-19 pandemic. Concerns about global warming and its consequences rank consistently high in voter polls. All parties have included chapters on their climate policy proposals in their election programmes. In Angela Merkel’s last summer press conference as chancellor, almost a third of all questions were related to climate policy. And the recent devastating floods in western Germany have brought the issue of extreme weather events, as well as climate change mitigation and adaptation, fresh into the headlines.

Within the climate policy complex, however, agricultural and food policy are not playing a major role in the campaign. This is in keeping with the general weight and attention given to the different sectors, their share in emissions, and reduction goals. The agriculture sector’s contribution to Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions (about 9% of total emissions in 2020) is small compared to the energy sector, industry, or the transport sector. In many ways, climate action in the farming sector is more complex and has not been researched and developed to the same extent as emission reduction techniques have been in other areas of the economy. While there are fierce debates among farmers and with environmentalists about changes and more climate action under the Common Agricultural Policy of the EU, headlines are mostly made by other climate and energy policies, for example a ban on short-haul flights, the switch from combustion engine to battery electric cars or the coal exit.

Info-Box: Types of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture

Carbon dioxide (CO2): Occurs when grassland and moorlands are drained and turned into fields.

Methane (CH4): Occurs mainly when ruminants (in Germany mainly cattle, dairy cows) digest their food (enteric fermentation) and when animal manure is stored and distributed on fields.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) (laughing gas) and NOx: Occur when manure and mineral nitrogen fertiliser is used on fields.

Ammonia (NH3) and NOx: Indirect source of nitrous oxide emissions: Ammonia (from fertiliser/manure) is a nitrogen compound that has adverse effects on biodiversity, waterbodies, and drinking water. Ammonia when turned into nitrous oxide is a climate gas.

Find data on CH4 and N2O and NOx emissions from the farming sector here.

In a recent poll, 42 percent of respondents said that a party's stance on agriculture is relevant in their voting decision, while another 42 percent said that this would only influence their vote very little or not at all. Decisions about more environmental and climate action on the fields have a direct impact on farms - of which there are around 262,700, but the impact that a sustainability transformation of the farming sector will have on the average consumer is not yet tangible for voters.

In the aforementioned poll, 75 percent of respondents consider it important that the food they consume is grown or produced in Germany. Meat consumption in Germany is slowly falling. But the idea that the price for 1 kg of beef could become four to six times higher if all the external costs of its production were to be incorporated in the price, has not been widely communicated. It is part of a proposal for the transformation of the agrifood sector by a government-initiated Commission for the Future of Agriculture (ZKL) which Chancellor Merkel said should be used to inform the next government’s agriculture policy.

The ZKL calculated that the farming sector causes around 90 billion euros in externalities every year. Around 11 billion euros a year would be necessary to establish a climate friendly farming sector. Since these costs can’t be covered with the current agricultural budget alone, they will have to be borne by society as a whole. This means, if all of the necessary measures are to be implemented and if farmers are to survive while abiding by all the new sustainability rules, food will have to become a lot more expensive.

Why is the shift to a sustainable agrifood sector such a controversial topic in Germany?

The past legislative period (2017-2021) was marked by the some of the largest farmers’ protests in Germany since the end of the second world war. When the government launched its “agriculture package” with new rules on animal welfare and insect protection, as well as earmarking more farming subsidies for environmental and climate measures in autumn 2019, tens of thousands of farmers took to the streets. They said that the new rules would make it impossible for family-run farms to compete, and that politicians and environment activists were labelling farmers as “animal abusers and polluters”. In the negotiations over the future funding distribution under the European Agriculture Policy (CAP), from which German farmers receive a substantial part of their income, they felt that their economic situation was playing second fiddle to environmental and climate concerns.

Info-Box: The EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)

Germany receives around six billion euros per year from the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy, which will enter a new funding cycle in 2023. The multiannual budget for the next funding period (running till 2027) will amount to 387 billion euros, around 26 percent of the EU’s total budget.

The CAP is financed through two funds as part of the EU budget:

First pillar: the European agricultural guarantee fund (EAGF) provides direct support to farmers according to the size of their farmed land, and funds market measures

Second pillar: the European agricultural fund for rural development (EAFRD) finances rural development, including agro-environmental measures.

With its 2020 Farm to Fork and Biodiversity strategies, the European Commission has pledged to decrease the carbon footprint of the food system and make farming more sustainable. With the new CAP, Farm to Fork objectives, such as farming 25 percent of EU agricultural land organically or lowering fertiliser use by 20 percent, should determine the way subsidies to farmers are allocated.

Environment and climate groups have long perceived the farming sector as particularly stubborn and defensive when it comes to adapting its practices to new environmental standards and accepting climate change mitigation as one of its objectives. Their attacks on the farming industry views on animal welfare, pesticide bans and meat consumption, have left the two sides estranged, to say the least.

A split along similar lines continues to prevail between the federal environment ministry – in the last legislative period led by SPD minister Svenja Schulze and the federal agriculture ministry – led by CDU minister Julia Klöckner.

To achieve some reconciliation and find common ground between the two groups, Chancellor Merkel initiated the “Commission for the Future of Agriculture” in 2020, bringing together 31 leading figures from agriculture, environment, consumer groups, and science. The commission’s final report was accepted unanimously and Merkel said that its recommendations should serve as a guideline for the next government. Members from the German Farmers’ Association (DBV), Friends of the Earth Germany(BUND) and the commission’s chairman all agreed that even if nothing further came from the committee’s work, one thing they had achieved was the ability to talk to each other, understand each other’s issues much better, and work as a team to find solutions.

While this sounds promising, some farmers criticise that the commission’s work does not make any difference for their problems in the here and now. Hence the issues which they had with the current government’s policy back in 2019 and 2020 have not been resolved. (Conventional) farmers themselves are therefore unlikely to vote for those who are advertising even stricter environmental obligations (e.g. the Green Party, SPD). Their vote is traditionally cast for the conservative CDU-CSU Union (over 60% in the general elections 2017, according to polls) or the pro-business FDP (14% in 2017).

As for the „average consumer” – they are handled with kid gloves by competing politicians. Ever since the Green Party’s “Veggie Day” debacle in 2013, eating habits are a no-go area in German campaigns. Some even blamed the Green Party’s lower 2013 election results on their proposal of public canteens not serving meat once a week. Asked whether Germans should reduce their meat consumption, SPD chancellor candidate Olaf Scholz said in July, that “the state should stay out of this kind of question”. “If someone voluntarily reduces their meat consumption after consulting with their family doctor or out of inner conviction, this is good for the individual and for the climate,” he added.

Asked the same question, CDU chancellor candidate Armin Laschet said: “We will have to compensate a lot. Because even in 2045 there will be no worldwide ban on meat. I prefer to work on pragmatic solutions now.“ He added that Germany with its high standards had to remain competitive, since production moving abroad, be it meat, steel or other products, would be even worse for the climate.

What are Germany's climate targets for the agriculture and land sector?

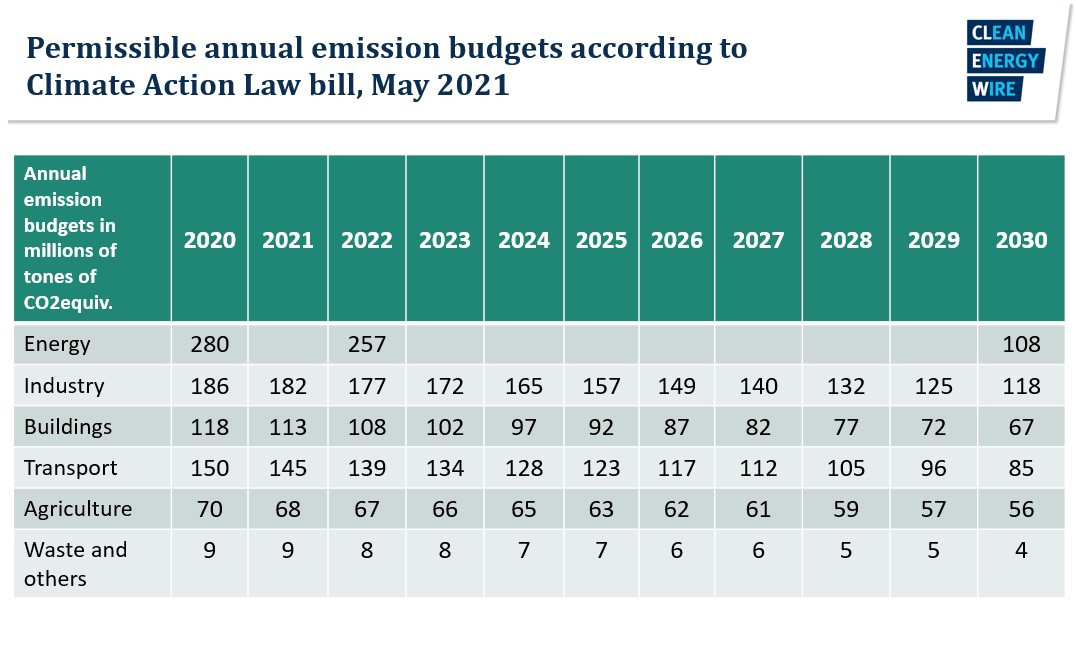

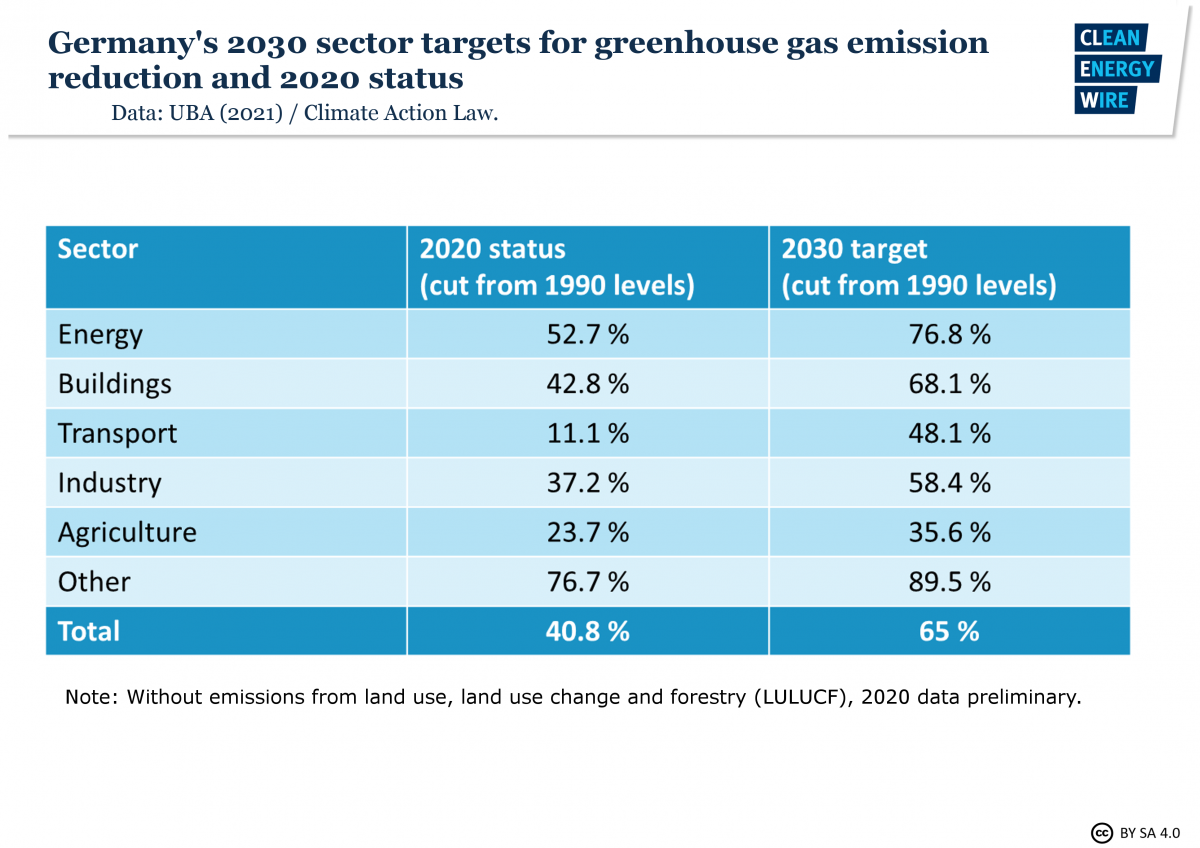

Germany has brought forward its target date for reaching climate neutrality to 2045, and has set annual emission targets for each sector to reach that goal. Emissions in the agriculture sector will have to drop by more than 35 percent within this decade (from 1990 levels). For each year until 2030, the sector has a certain emission budget – it will have to reduce CO2equiv. from 66 million tonnes in 2020 to 56 million tonnes in 2030.

What's the state of play in Germany's shift to low-emission agriculture?

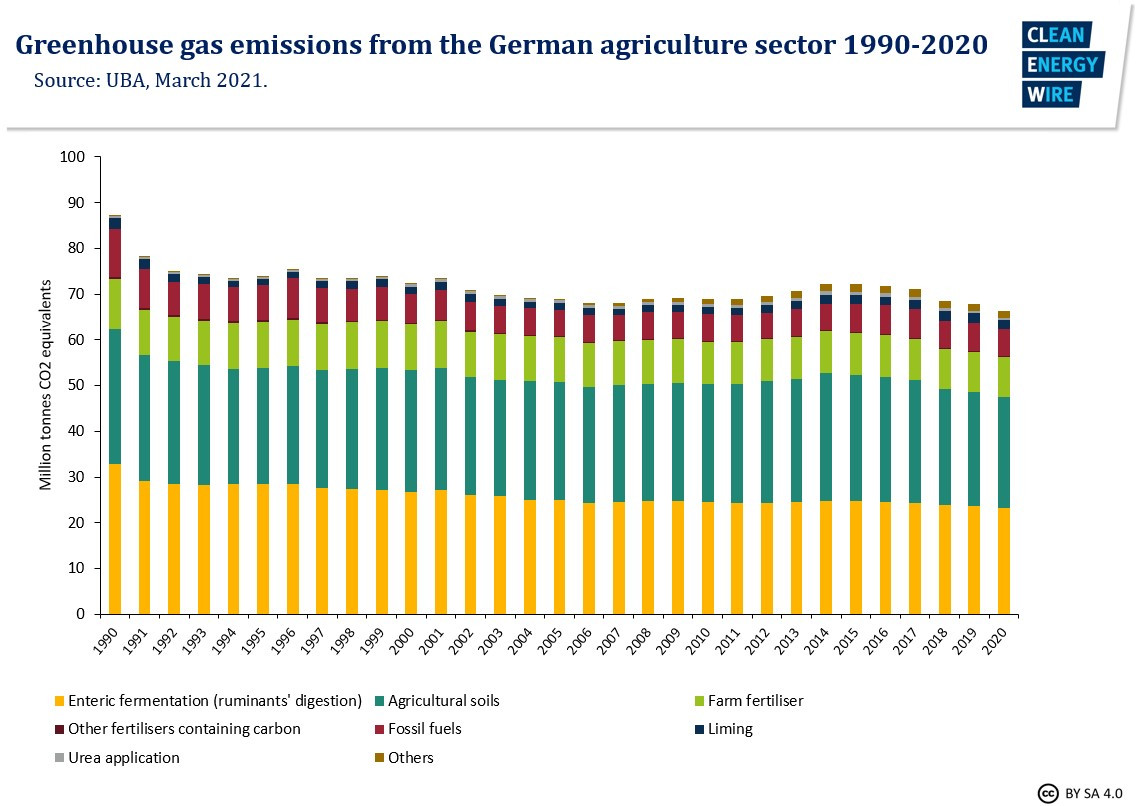

Agriculture emissions in Germany have fallen by around 24 percent since 1990, in large part due to the decrease in livestock numbers and the structural transformation in the former GDR after German reunification. From 2017, greenhouse gas emissions from the sector started to decrease significantly again, as a consequence of several drought years. High crop yield losses and lower mineral fertiliser use also impaired feed supply for animals, which is likely to have contributed to a reduction in livestock numbers (especially in cattle farming). This trend is continuing, the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) says.

Another part of farming-related emissions fall under the category of land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF), which is not included in the current reporting under the sector emission targets. The overall emission budget for LULUCF in Germany is negative, meaning that this category is an overall sink that stores more greenhouse gas than it emits per year. In 2016, LULUCF stored around 14.5 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents. The biggest emitters of greenhouse gases (mainly methane) are croplands and grasslands, while forests are the biggest sink. In its 2021 amendment of the Climate Action Law, the government for the first time included contribution targets for the LULUCF sector: by 2030 it’s CO2eq uptake should amount to net 25 million tonnes and by 2045 to net 40 million tonnes. In 2020, the UBA estimates that LULUCF stored around net 16.5 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents in Germany.

The Climate Action Programme 2030 includes measures such as the reduction of nitrogen surpluses, strengthening of the fermentation of manure of animal origin, the expansion of organic farming (to 20 percent of agricultural land), and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in livestock farming as well as the promotion of carbon storage potentials in agricultural lands, for example humus build-up.

The ZKL proposes to raise the share of organically farmed land to 25 percent by 2030. It also advocates moorland rewetting and humus build-up; tying the size of cattle herds to the size of available land, with a focus on pasture-based cattle farming; and reducing nitrous oxide (laughing gas emissions) caused by the use of nitrogenous fertilisers.

What do the parties plan?

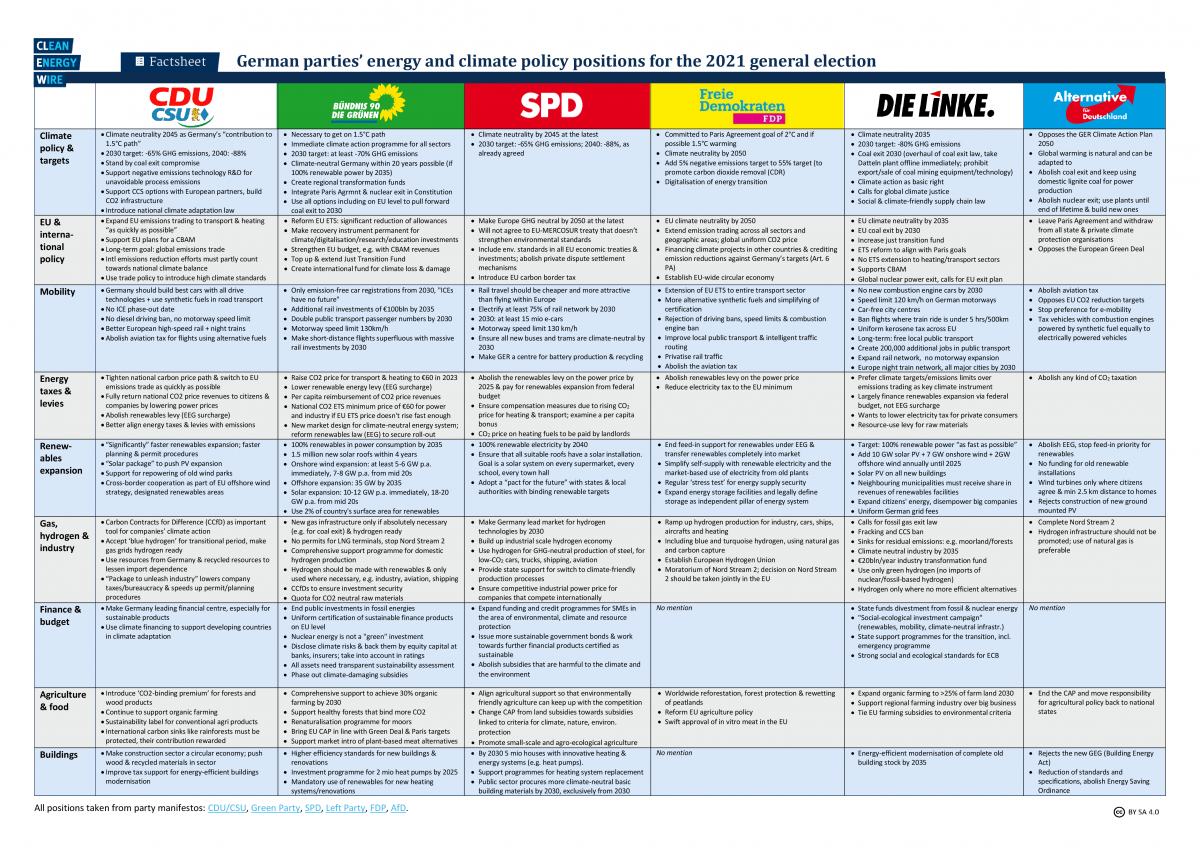

The election programmes of Germany’s political parties all include plans for the agriculture sector but few provide details on actual measures or how proposed changes will be financed.

The Green Party, the Social Democrats (SPD) the Liberal Democrats (FDP) and the Left Party propose a reform of the CAP to align support payments to farmers more closely with the fulfilment of climate and environmental measures.

The SPD wants to promote small-scale and agro-ecological agriculture and the Left Party wants to expand the area for organic farming to over 25 percent by 2030.

The Green Party wants to support the market intro of plant-based meat alternatives and the FDP promotes a swift approval of in vitro meat in the EU.

The CDU-CSU wants to introduce a “CO2-binding premium” for forests and wood products and a sustainability label for conventional agrifood products.

Positions of some main stakeholders ahead of the elections

In a way it is a peculiar situation that, only a few months before the general election, almost all stakeholders in the agriculture sector have shown their cards and, in the ZKL report, agreed on a compromise on what a sustainability transformation should look like. Likewise, the criteria for how the money from the CAP will be spent in Germany has also been largely set for the next six years.

The ZKL report has not given any details, for example on exactly which moorlands should be re-wetted, how much money a farmer would receive for that, or which rules should be established to reduce cattle etc. Positions on implementation vary and many decisions on the details will have to be taken by the next government.

Germany’s largest farmers’ association, DBV demands ahead of the elections:

- A strong first pillar of the CAP (i.e. direct payments to farmers) and income-generating support for public services by farmers through the second pillar

- Common standards on the EU internal market without special national approaches; create legal framework for a “Germany bonus” wherever European standards are exceeded

- Reward the achievements of agriculture and forestry in climate protection

- Mandatory labelling of farming methods and origin; preserve livestock farming in Germany

- Fight unfair trading practices and abuse of market power in the food supply chain more effectively

- Further develop export markets with purchasing power for high-quality and sustainably produced agricultural products

- Comprehensive nutritional education for consumers instead of paternalism; no restriction of the diversity of supply

The DBV has also criticised the current rules for eco-schemes under the new CAP as being still too vague and not attractive enough for farmers in favourable locations, and said that changes should be made in autumn 2021.

The DBV is calling for a border tax on food imports for agricultural goods produced under less stringent standards, similar to the carbon border adjustment proposed by the European Commission.

The German Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU) has listed these demands for the agrifood system ahead of the elections:

- A fundamental reorganisation of the support system for the agricultural sector under the CAP: By 2028, the flat-rate area payments must be replaced by an ecologically effective and fair system of remuneration for concrete environmental services

- Reform best practice rules in forestry and agriculture, create legally binding standards of “good professional practice” to achieve the goals of the EU Farm-to-Fork and biodiversity strategies

- The government must, in line with the European Green Deal, ensure that 10 percent of agricultural land is used exclusively for ecosystem services and not cultivation

The Climate-Alliance, supported by farmers’ association AbL demands:

- Reduction of nitrogen surpluses via a nitrogen levy, which is used to reward climate-friendly agriculture

- At least 70 percent of the CAP funds to be used for voluntary income-generating services in the areas of climate, environmental and species protection; for this purpose, the eco-schemes in the 1st pillar and the promotion of agri-environmental and climate protection measures in the 2nd pillar of the CAP should be significantly expanded

- Protect sustainably and climate-friendly produced goods in the EU from dumping prices from third countries

- Further develop quality standards for exports

- Implement measures to reduce enormous land use and deforestation in third countries; fodder imports may not contribute to deforestation or human rights violations

For a detailed overview of the ZKL’s proposals see this factsheet.

What has the outgoing government achieved?

Farming minister Julia Klöckner (CDU) and environment minister Svenja Schulze (SPD) in 2019 introduced the “agriculture package” (which triggered huge protests, see above). The proposed legislation included shifting funds from the 1st to the 2nd pillar of the CAP (where they are more used towards environmental and climate protection), a new animal welfare label, insects protection by banning the pesticide glyphosate by 2023, and a reform of the fertiliser regulation to reduce nitrate surpluses. This is what became of the agriculture package by the end of the legislative period:

- The new fertiliser regulation came into force in May 2021 – the amendment had been necessary because Germany was in breach of EU Nitrate Directive, obliging member states to reduce nitrate pollution

- In spring 2021, the 16 state agriculture ministers agreed on how the CAP funds should be distributed in the next funding period until 2027. More funds will go into the 2nd pillar of the CAP and more will be used for voluntary eco-schemes.

- The environment ministry’s proposal for a moorland protection strategy failed as a compromise with the agriculture ministry could not be reached

- Although the cabinet agreed a draft law in 2019, the (voluntary) animal welfare label as proposed by the agriculture ministry was stopped in parliament amid objections from environmental organisations and other stakeholders who pushed for a mandatory label and different criteria

- The insects protection act was passed by the federal parliament in June 2021

In autumn 2020, agriculture minister Klöckner presided over several sessions during Germany’s EU Council Presidency regarding the future CAP. She was not perceived as a driving force for more ambition by environment and climate groups.

In December 2020, Germany’s agriculture ministry launched a 1-billion-euro ”Farmers for climate action” package, including an investment programme worth 816 million euros to boost the use of new technology in farming.