The EU’s Carbon Border Tax — panacea or recipe for trade war?

Content:

- Why the carbon border adjustment and what does it do?

- Which goods will the EU carbon border price apply to?

- How will the EU’s carbon border adjustment work?

- Interaction between CBAM and EU ETS

- How much revenue could be generated by the tax and what will the money be used for?

- Key legal issues when implementing CBAM

- What do Europe’s trading partners think about a carbon border tax?

- What do European and German industries think about a carbon border adjustment?

Note: European Institutions agreed a deal on CBAM in December 2022, in which they decided to implement it gradually from 2023, initially only with reporting obligations. However, the final text of the agreement was not yet available at the time of the update of this factsheet. The information on the deal in this factsheet is based on press releases by the institutions. The full extent and implications of the new system will only become clear once the text is formally agreed and published.

-

Why the carbon border adjustment and what does it do?

The European Union wants to become climate-neutral by the middle of the century. To achieve this and meet medium-term targets, the EU has set up a carbon emissions trading scheme (EU ETS) as a key part of its climate legislation.

Putting a price on emissions gives an incentive to domestic companies to work and produce in an increasingly climate-friendly manner, but the European Commission is worried that this leads to a competitive disadvantage and ‘carbon leakage’ if the EU’s trading partners are not pricing carbon in a similar way.

What is carbon leakage?

Carbon leakage occurs when companies shift their carbon-intensive production activities from regions with tough emission reduction policies (e.g. a high carbon price) to a place with more lax policies. The same happens when companies located in countries with stricter emissions regulation reduce output due to high carbon costs, while their counterparts in places with a smaller regulatory burden increase production. As a result, the emissions saved in the place with tight emission regulations are instead emitted in another country (leakage), meaning there is no greenhouse gas emission reduction overall.

While almost all nations are signatories to the Paris Agreement and are therefore ostensibly bound to a similar pathway to reach net-zero emissions, the actual price for CO2 and the environmental standards in manufacturing differ widely across countries. Carbon leakage could then mean that – overall – emissions would then not be reduced, despite the European efforts.

Another concern is the potential loss of competitiveness in European industry, whose manufacturing costs for the same materials, e.g. steel, are higher because of CO2 pricing. This could lead to European industry being undercut by others on the global market making it harder to stay afloat.

These issues could be alleviated by a so-called carbon border tax or adjustment. Simply put, such a levy would add the same CO2 costs to a product when it crosses the border into the EU that the manufacturer of a domestically produced item would then have to pay.

The EU is referring to this instrument as ‘carbon border adjustment mechanism’ or CBAM. It is the world’s first concrete proposal to impose carbon emission costs on imported goods at an international border.

2. Which goods will the EU carbon border tax apply to?

The CBAM will apply to imports of certain goods from all non-EU countries, unless they participate in the EU ETS or have an emission trading system linked to the ETS (such as Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein).

As per a December 2022 agreement between the EU parliament and member states, the CBAM will cover iron and steel, cement, aluminium, fertilisers and electricity. It also covers hydrogen, indirect emissions from the production of particular materials (e.g. from the electricity used to produce aluminium), certain precursors, as well as to some downstream products such as screws, bolts and similar objects made from iron or steel. Overall, it thus covers more than 50 percent of the emissions of the sectors covered by the ETS.

During the transition period, only direct emissions will be covered, with indirect emissions following further down the line.

The Commission decided that the CBAM will cover these key goods based on three criteria: they are at high risk of carbon leakage because they are carbon-intensive, they are goods which are highly traded, and the application of this mechanism is practically feasible for them.

At the end of the transition period, the Commission will assess whether other goods should be included, such as organic chemicals and polymers. By 2030, the goal is for CBAM to include all goods which are also covered by the EU ETS. The Commission will also look at the possibility of including more products made from the goods covered by CBAM.

3. How will the EU’s carbon border adjustment work?

The regulation obliges companies that import into the EU to purchase so-called CBAM certificates to pay the difference between the carbon price paid in the country of production and the price of carbon allowances in the EU ETS.

Each year, importers will need to declare the quantity of goods imported into the EU from the preceding year and the associated greenhouse gas emissions. They will then hand over the corresponding number of CBAM certificates. Any CO2 price that they already paid in a third country will be deducted. The price of the certificates will then be calculated depending on the weekly average auction price of EU ETS allowances expressed in euros per tonne of CO2 emitted.

According to the deal from December 2022, CBAM will:

- Enter into force in its transitional phase on 1 October 2023. During this phase, the obligations of the importer shall be limited to reporting, without making any financial payments or adjustments. This will also help the national authorities that will have to put a new system in place for the registration of importers, the review and verification of declarations, and the sale of CBAM certificates.

- It will gradually be phased in from 2026-2034 (while free allocations to emitters in the EU ETS are being phased out at the same time).

4. Interaction between CBAM and EU ETS

The EU's main mechanism to prevent carbon leakage from industry is the allocation of free CO2 emission allowances under the EU ETS. Under the ETS, free emission rights are given to energy-intensive companies that meet product-related benchmarks and are deemed to be at risk of carbon leakage. In addition, member states are permitted to return some of the ETS revenue to electricity-intensive businesses.

As the CBAM also provides carbon leakage protection, the two instruments have to be closely coordinated to avoid putting too much pressure on either importers or EU producers. The European Commission stated that the CBAM will ‘progressively become an alternative' to the free allocation of allowances under the ETS.

European institutions have now decided to gradually phase out free allowances and end these by 2034 (2026: 2.5%, 2027: 5%, 2028: 10%, 2029: 22.5%, 2030: 48.5%, 2031: 61%, 2032: 73.5%, 2033: 86%, 2034: 100%).

Until then, the CBAM will only apply to the proportion of emissions that does not benefit from free allowances under the ETS, “thus ensuring that importers are treated in an even-handed way compared to EU producers,” as the Commission stated.

5. How much revenue could be generated by the tax and what will the money be used for?

The CBAM could bring in additional revenue of around 9 billion euros per year by 2030, according to the Commission’s impact assessment report. The largest part would be generated through additional revenues in the ETS once free allocations are phased out. Only about one fifth of total additional income would actually come from revenues collected at the border through the CBAM.

According to European Parliament member Mohammed Chahim, who led the parliament’s negotiation team, European institutions agreed that an equivalent amount to the income generated through the CBAM should be used on climate action, such as supporting least developed countries and climate finance in general. This would help make the scheme World Trade Organization (WTO) compliant.

European Commission officials have stressed that revenue is not the reason why the EU is proposing the introduction of a CBAM.

6. Key legal issues when implementing CBAM

One major challenge for the mechanism is designing it within WTO rules. The EU is bound by the WTO’s free trade principle of ‘non-discrimination’ (contained in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade – GATT), and this would be breached if the bloc differentiated between low and high-carbon products that are otherwise alike.

The GATT provides for exceptions to this rule for environmental reasons, but the CBAM would have to be designed to meet the requirements exactly.

The current practice of giving free allocations to industries that are at risk of carbon leakage when a CBAM is in place could be construed by the WTO as an export subsidy, which is prohibited under the WTO’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM), according to a paper published by European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition (ERCST).

EU institutions have said their deal means the CBAM “is designed to be in full compliance with World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules,” also because it is paired to the phasing out of free allowances under the ETS.

Are there other issues regarding carbon border adjustments?

Depending on the exact design and the actual carbon cost used for the mechanism, the following risks or issues have been flagged by researchers and stakeholders:

- Some researchers have pointed out that carbon leakage is only a ‘perceived’ threat for which there is too little evidence. Opponents of the tax have therefore argued that the CBAM would yield little benefit and impose many costs.

- If the EU’s emissions regime is joined by other large economies, such as the U.S. and Japan, high barriers between this trade bloc and the rest of the world would shut out emerging and developing economies.

- If Europe alone implements a high carbon levy, only very low-carbon producers would be able to trade with the EU, high-carbon trade would continue but bypass the EU, and eventually European producers would have to increase their production output.

- Apart from the actual carbon content of a product, compliance with the new EU authentication and reporting rules set up by the CBAM could accidentally discriminate against producers from less developed countries.

- A carbon border adjustment system should aim to specify the exact amount of emissions linked to each product, ideally including emissions along its entire value chain – this is difficult, especially if a product is manufactured using electricity, e.g. aluminium.

- Trade deviation and carbon leakage: exporters from high-carbon countries could sell their products to other countries which do not have a carbon border tax, thereby replacing less carbon-intensive domestic production there.

- Distorting trade and damaging EU industry: If the CBAM prevents EU manufacturers from importing raw materials, e.g. steel, from a high-carbon country, the EU will likely import manufactured products (e.g. nails) instead from those countries – making life difficult for European producers of such downstream products.

- Trade war: Depending on its design and the impact the CBAM will have on industries in different countries, their response may be to push back with their own tariffs (read more below).

7. What do Europe’s trading partners think about a carbon border tax?

With the CBAM, the EU’s aim is to avoid carbon leakage and “motivate foreign producers and EU importers to reduce their carbon emissions, while ensuring that we have a level playing field in a WTO-compatible way,” Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said in September 2020.

In this sense, the CBAM is part of Europe’s climate diplomacy and, even before a proposal has been adopted, observers credit it with having helped change attitudes towards climate action in other countries. With more countries drafting their own national climate policies and greenhouse gas reduction measures for industry, they too are faced with their effect on competitiveness and with the issue of carbon leakage posed by the CBAM. This means there is some sympathy for the EU’s carbon border adjustment approach, said Michael Mehling, a researcher at the Centre for Energy and Environmental Policy Research (CEEPR) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), to Euractiv. In 2021, the European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition (ERCST) published a paper on the status of discussions on border carbon adjustments (BCA) around the world, which shows that the EU is not alone in considering such a scheme.

But while the EU wants to exert its power to ‘do good’ and promote climate action in countries around the world it trades with, these same trading partners may not like to see their hands forced in this way and could “reflexively push back against the CBAM,” according to an ERCST paper.

Researcher Arvind Ravikumar even considers unilateral carbon border adjustments “the latest form of economic imperialism” that is “antithetical to the principles of equity enshrined in the Paris Agreement.” A similar stance is taken by Oxfam Kenya, which suggested that there are other policy instruments which could be used to avoid carbon leakage that would not be so harmful to developing countries, e.g. import standards regulation.

Large trading partners, such as Russia, India and China, could introduce countermeasures, i.e. import tariffs of their own. Some have therefore warned of a trade war, caused by the EU introducing a CBAM.

Overall, it is important to note that the effect of the CBAM on trade with a certain country depends very much on the goods and sectors included in the mechanism and the particular manufacturing conditions and climate measures in place in this country. Countries with relatively clean energy mixes (e.g. Costa Rica) and with carbon prices of their own, would not have to bear the border tax. While others with high shares of coal power and carbon-intensive industries, such as South Africa and India, would likely have reason to oppose such a measure.

China

China produces half of the world’s steel and it is thus very exposed to the CBAM. The Chinese government voiced its concerns over a carbon border tax as early as 2019, saying it would damage the global fight against climate change. Yet, within China reactions are more varied, as a China Dialogue report showed that there are businesses that already produce with small carbon footprint. These businesses are well positioned to increase trade with Europe once the CBAM is implemented. Others, however, would have to adapt quickly and could be helped by emissions trading for goods that are covered by a CBAM. According to Dimitri de Boer, head of ClientEarth’s China office, whether a CBAM would spark a trade war with China or motivate the country to increase its own emission reduction efforts from industry hangs in the balance.

Russia

In the past, the EU was Russia’s largest trading partner, and Russia the EU’s fifth largest trading partner. Of all countries, Russian exports were most exposed to the CBAM among all trade partners. Main EU imports from Russia were raw materials, oil, gas and metals (iron/steel, aluminium, nickel). However, EU trade with Russia has been strongly affected following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, with the EU imposing import and export restrictions on several products.

In June 2021, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said that a CBAM “may clash with global trade rules and threaten the safety of energy supplies.”

Ukraine / Turkey / India

At least until the start of the war, Ukraine’s main exports to the EU were iron/steel, mining products, agricultural products, chemical products and machinery. In its response to the European Commission’s impact assessment consultation, Ukraine’s Ministry of Economic Development, Trade and Agriculture voiced concerns about the CBAM’s effects on the steel industry in particular. The Ukrainian steel industry association UKRMETALURGPROM pointed out that the country’s own carbon tax and willingness to integrate into the EU’s Green Deal initiatives mean that “trade in steel goods […] should not be subject to any CBAM.” The Ukrainian think tank GMC Center calculated a high risk for a decline in the country’s power, chemicals and steel exports to the EU, coupled with a subsequent job loss and the deterioration of trade relations, should the CBAM come into force.

The Turkish Business and Industry Association (TUSIAD) and Ukraine’s Ministry of Economic Development have both expressed an interest in aligning their policies with the EU standard and asked for a mechanism and funding to facilitate this approach.

India is said to be planning to raise the issue of the EU’s CBAM at the WTO level, while also exploring the possibility of having its own CBAM, “based on per capita emissions or per capita cumulative (historical) emissions,” reported The Hindu Business Line. The EU’s imports from India are manifold, with textiles, chemicals and metals all playing a role. The Boston Consulting Group has pointed out that, for example, India’s (and Turkey’s) steel industries would probably pay less tax than other sectors because of their higher share of minimills, which are generally more carbon-efficient.

U.S. and Canada

During his campaign for president, Joe Biden embraced the aim of imposing “carbon adjustment fees or quotas on carbon-intensive goods from countries that are failing to meet their climate and environmental obligations”. U.S. lawmakers have since come out in favour of introducing a border levy. The U.S. government reportedly suggested the creation of an international consortium with the EU which would promote trade in metals produced with less carbon emissions, while imposing tariffs on steel and aluminium from China and elsewhere. However, this initiative has seen little movement so far, and the U.S. inflation reduction act has led to a clash with European countries. Thus, as U.S.–EU trade tensions rise, conflicting carbon tariffs could undermine climate efforts, as voiced by several researchers in The Conversation.

From the start, politicians and industry in the U.S. kept a wary eye on the EU’s plans, arguing that new trade disputes could be triggered if a CBAM should penalise U.S. companies for not having a carbon price when they are reducing emissions through other measures. EU climate Commissioner Frans Timmermans said the U.S. could be exempt from the CBAM if it has similar climate policy, but the final deal seems to say that an explicit carbon price would be necessary – which the U.S. does not have.

Like the U.S., Canada’s government is also exploring the introduction of a border carbon adjustment scheme but plans have not been advanced as far as the EU’s.

8. What do European and German industries think about the carbon border adjustment?

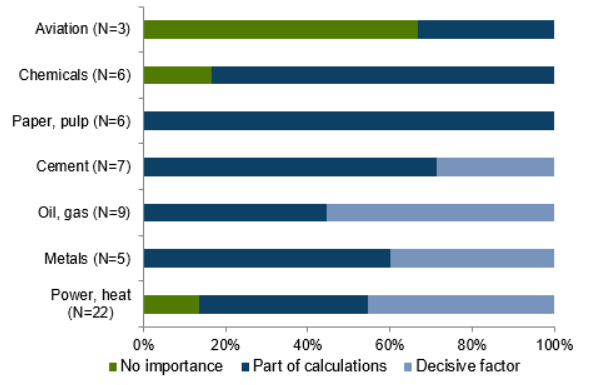

Attitudes towards a carbon border fee amongst European industries depends very much on the specific industry in question, and the design of the mechanism. In a summary of the public consultation that ended in October 2020, the ERCST found that “stakeholders remain positive towards the border adjustment, but worried about the impact on the current domestic measures to address carbon leakage and the functioning of the EU ETS at large.” Over the course of the legislative process, European industry called for some of the free allowances in the ETS to remain to ensure that companies stay competitive.

After Parliament, Council and Commission reached a deal on CBAM in December 2022, European and German industry remained critical, especially as a key issue was not decided: the question of how to ensure that companies which no longer receive free allowances and export large shares of their products to extra-EU countries could remain competitive globally.

The European Steel Association’s director general Axel Eggert said “We are highly concerned by the lack of a concrete solution to counter carbon leakage risk on export markets, while a predetermined free allocation phase-out trajectory is set at this stage. If no concrete solution is found by 2026, 45 billion euros worth of steel exports are at existential threat, due to the exponentially increasing carbon price in the EU that has no equivalent in the domestic markets of our major trading partners. It is essential that EU institutions revert to this issue as soon as possible in the foreseen review process to deliver an effective measure”.

German steel federation WV Stahl agreed that the lack of a solution for exports leads to planning uncertainty for the industry in transformation. In addition, an inadequate conception of how carbon leakage can be prevented on export markets also significantly jeopardises the effectiveness of the ‘climate protection contracts’ – support for companies that switch to more climate-friendly processes. Support through these contracts would be based on effective border adjustment. “This gap must be closed and internationally competitive framework conditions created,” said WV Stahl in a press release.

Chemicals industry association VCI said big question marks remained and businesses feared a ‘thicket of bureaucratic procedures’ for European companies, while those in the U.S. profited from unbureaucratic support through the inflation reduction act rules. However, the industry was happy that at the start only few of its products would be covered by CBAM (e.g. ammonia), a spokesperson from the VCI said. The association said free allocations for industry had worked well in the past.

The head of the Association of Bavarian industry (vbw) Bertram Brossardt criticised the postponement of a decision on support for companies that export products covered by CBAM, but which no longer receive free allowances in the ETS. “If the instrument is introduced, it must be practicable,” added Brossardt. “Trade conflicts must be prevented at all costs, as well as new bureaucratic burdens. In addition, it is essential to find solutions for dealing with multi-linked value chains. There must be no further price increases for processing companies in the EU and EU exports must remain competitive on the world market.”