Leading from behind – Germany's government sparks green finance to drive climate policy

In early 2019, a German government committee usually of little consequence to the country’s bankers, insurers and asset managers put out a note that sent a small shock wave through those circles. In the note, the State Secretaries’ Committee for Sustainable Development called for measures to make Germany “a leading location” for the bourgeoning green finance market. Business prospects were, however, not the key motivation. Instead, policymakers were looking for ways to keep the finance industry from undermining climate policy through investments in emissions-intensive projects and instead encourage them to help fund the transition to a more sustainable economy.

The level of ambition on the finance side was new to Germany. While financing for projects that bolster climate action and other environmental or social protection measures has grown rapidly in many countries in recent years, Europe's biggest economy is far from leading the pack. Despite its many years of experience with the Energiewende, the parallel phase-out of fossil and nuclear power and the creation of a more efficient energy system based on renewables, the country has been rather slow in exploiting the business potential for its financial sector – especially since renewables have become cheaper than fossil fuels and now cover 40 percent of global energy consumption growth.

Germany has also been slow to factor in the possible costs and risks of climate change and the political reactions it produces. The danger of the so-called carbon bubble, the idea that fossil-based assets and carbon-intensive technology will substantially lose value if Germany’s emissions-reduction targets are enforced, could test the adaptability of a country that owes its prosperity to many carbon-intensive industries. Already in 2016, a report by the German finance ministry (BMF) found that a substantial CO2 price increase could wipe hundreds of billions of euros off its most important companies’ portfolios and inflict “severe losses” on the economy. But as of 2019, it appears financial markets have yet to be convinced that governments are serious about climate action.

Four years after signing the Paris Climate Agreement, and amid growing voter concern over global warming and persistent protests to contain its impact, the government in Berlin must now put mechanisms in place so the country’s financial 'engine room’ doesn’t upend efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Shortly after the state secretaries’ announcement, Chancellor Angela Merkel acknowledged that the financial sector must quickly find “a strategy” for regulatory changes that will impact its core mechanisms. These changes are also looming at the EU level in the form of a sustainable finance framework and domestically as a set of far-reaching climate policy steps. This includes, for example, a mechanism for comprehensive and cross-sectoral carbon pricing, to be bundled in a national climate action law by late 2019.

Germany's public banking sector could spur green finance expansion

One of the first strategic measures the government has taken is to launch a sustainable finance council. The joint initiative by the finance (BMF) and the environment (BMU) ministries seeks to bring together industry, policymakers and civil society to scout out a possible course of action. This group works on greater investment transparency and a coherent disclosure of climate risks, better communication of alternatives to small and large investors and the integration of Germany into international efforts to apply environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria in financial markets while keeping these markets stable.

“We’re seeing now that the finance ministry has woken up to the topic, but I can’t say yet how serious it is going to be in the end,” said council member Gerhard Schick, founder of the NGO Finanzwende. Schick, a former Green Party finance politician who resigned his seat in parliament in 2018 to become and activist for a finance sector transition, said that a political plan is indispensable if finance is to make a contribution to climate action. Too many practices and targets are “in complete disregard of one another” and make climate and finance policy inconsistent, he said.

Defining which investments are desirable and which are not is crucial for the government to reconcile its own financial activities with its climate aims and to set up guidelines to hedge in financial firms. Up to 20 percent of German government assets under management are in Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), index fund that reflect selected segments of the market and do not apply sustainability criteria, Schick said. And the remaining assets have not been systematically adapted to the country’s climate goals, he added. Indeed, a 2019 government investment advisory panel stated Germany’s principle investment approach should keep a “moderate” sustainability profile in order to “not restrict the investment universe too much”.

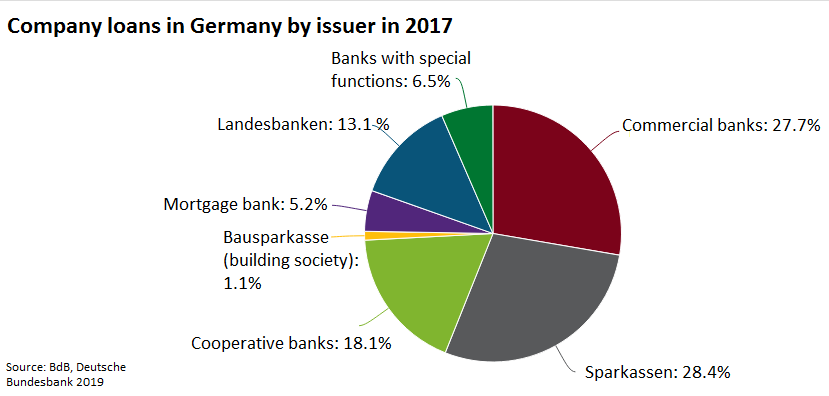

But hard criteria that are binding for everyone are needed and the public sector should be at the forefront in shaping and implementing them, Schick said. Germany's public banks, the Sparkassen and Landesbanken, and its public insurers are peculiar features of its financial system. The Sparkassen are usually owned by the local community they operate in and are obliged by law to “work towards the public good” rather than seeking profit maximisation. With aggregate assets of about 1.2 billion euros, they rival the biggest commercial banks and reach far more customers across the country thanks to their dense branch network.

Together with the Landesbanken, which are owned by Germany’s federal states, public institutions account for more than a quarter of the banking sector’s total assets. Although the state-owned development bank KfW has long been a driving force in financing energy-efficiency and green projects domestically and abroad, it is dwarfed by the clout of Germany’s public finance institutions. If these had a coherent strategy geared to address climate challenges, Germany could develop a market of significant scale much more quickly than most other countries without a public banking sector, Schick said. “If the political parameters were to change, I’m sure we’d see massive changes setting in quickly – this might actually deliver on making the country a leading sustainable finance location”.

Industry yearns for clear climate investment pathway

Pressure to change tack looks set to mount. Economic heavyweights like Germany’s major chemical producers or the mighty car and machinery industry, with its thousands of suppliers, long for regulatory clarity to adapt their investments to climate policies and avoid losses if people were to shun their products. A joint proposal for a sustainable finance “roadmap” by Germany’s stock exchange, Deutsche Börse, together with environmental organisation WWF, testifies that industry and NGOs alike see great need to address this issue. “Pitting sustainability against profitability has to end by pricing in sustainability risks,” found the authors of the roadmap supported by finance industry network GSFC.

The German government has come to realise that these risks have in fact “not been considered too extensively” for a long time, a finance ministry source said. But political pressure and pending EU legislation have goaded policymakers, shown by Germany quickly joining intergovernmental networks like the central banks’ green finance initiative or a finance minister coalition for climate action. The government in Berlin did support rapid legislative negotiations on carbon disclosure, the finance ministry source said. However, it is more sceptical of the EU plan’s centrepiece, a Europe-wide taxonomy for classifying and ranking investments by their degree of sustainability. The idea is to provide a commonly accepted trading label – an ambition both complex and prone to conflict.

German views have clashed with those of other members, for example over including nuclear power generation, which some praise for being largely free of greenhouse gas emissions, but others disqualify due to dangers in operation and waste-storage. “It is unclear if whatever follows from taxonomy will be practicable in reality”, the ministry source said.

Too many competing definitions for identical products and meticulous instructions with strict limitations on portfolio composition could discourage companies from seeking a green label for their products. If the intention is to create a flourishing green finance market, companies should not be scared off by red tape. “This is a more cautious approach that might sometimes come across as hesitant,” a ministry spokesperson told Clean Energy Wire.

Green German state bonds could initiate screening of national budget

Another option for Germany to instantly give its sustainable finance market a push could lie in one of its own financial products: German government bonds, widely sought for their stability, have become a benchmark on international capital markets. Green bonds, a credit instrument that guarantees lenders fixed returns over a given term and ties investments to certain environmental standards, are already widely used by investors in Germany and Europe to finance clean energy and climate action projects. Germany’s government has until now stayed clear of the market but now plans to combine the instrument’s popularity with climate policy aims.

In order to back the green credentials of its government bonds without compromising their stability, the government is considering screening the national budget for existing expenditures that can be labelled green to help determine the volume of issuance. In essence, the green bond initiative would mean the government assesses options to establish its own ESG-taxonomy, which would then also serve as a concept for the state’s biggest asset, for example its civil servant pension fund VBL, the finance ministry source said. The ministries active in Germany’s climate cabinet, which brings together the members of government with direct influence on national emissions levels, will have to vet their expenses and disclose the climate impact of all items in the budget. “It appears not every minister has already understood what they are facing,” the source said.

The funding gap - climate policy needs allied finance sector

Implementating the Paris Agreement and achieving international emissions reduction targets will require enormous financial investments. According to UN calculations, these could reach the equivalent of up to 15 percent of individual state budgets or up to about seven trillion dollars per year globally. The shift to renewable energy sources, electric mobility, digitalisation and other measures associated with the energy transition therefore needs to be backed by a parallel decrease in fossil fuel investments and a rise in the funding of low-carbon alternatives and energy-efficient technology through a systematic inclusion of the financial sector in climate policy.

State governments rely on banks, insurance companies, investment funds and other financial market actors to act in alignment with climate policies. For Europe, the goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2030 is exacerbated by an annual funding gap of about 180 billion euros, the European Commission estimates. Germany alone would require additional investments of about 2.3 trillion euros to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 95 percent by 2050, equivalent to more than 70 billion euros per year, according to a study by industry federation BDI. Germany’s total federal budget for 2019 stood at about 356 billion euros.

The carbon bubble - finance sector needs clear climate policy

Global warming causes the financial sector faces two differents kinds of challenges at the same time. Financial investors not only face the immediate costs of more frequent extreme weather events but also a sudden devaluation of trillions in fossil assets due to unregulated divestment, as emissions reduction targets mean a large share of known reserves will have to stay in the ground. A mass withdrawal of funds invested in coal, oil and other fossil sources could let stock values plummet, turn balance sheets upside down and, by extension, deal a blow to pension schemes, insurers and government budgets around the world – a phenomenon known as the "carbon bubble".

A 2016 report by Germany’s finance ministry (BMF) assessed the impact of climate change and of possible political reactions to it from financial markets. The immediate effects of global warming on the financial system were considered negligible, at least in the medium run, but it found that an “orderly transition” to climate-neutral investments was necessary to avoid “severe losses” in the form of stranded assets, such as coal plants, in the case of abrupt carbon price rises that could destabilise the entire market. It also found that the value of the DAX, Germany’s most important stock market index, and the corporate bond market depend to a large extent on the business fortunes of high-emissions industries, especially producers of chemical and industrial goods and of cars. If companies were to internalise the costs caused by their greenhouse gas output through a higher carbon price, for example, this could wipe off more than 650 billion euros or five percent of company portfolios, even at still relatively low CO2 prices of 2016.

The ESG criteria - sustainability for investments

In order to minimise the disruptive effects of climate change and political responses to it on financial marekts, the Paris Agreement has stipulated a harmonisation of financial flows and emission reduction targets as one of its long-term objectives. This "shifting of the trillions" is meant to happen on two dimensions: First, by ensuring that investments do not run counter to emission reductions and, second, by raising capital for climate action measures. This implies systematically drying up financial flows that clash with reduction targets as well as a set of financial market reforms, such as a mandatory disclosure of climate-related risks, “Paris-compatible” investment criteria, adequate CO2-pricing schemes, stress-tests for credit systems, cutting fossil subsidies and decarbonisation roadmaps for industrial companies.

All of these measures are comprised in the concept of sustainable finance, which aims to ensure that the full impact of investments is understood and resulting risks are weighed against potential profits accordingly. Sustainable finance typically is based on so-called ESG criteria, which gauge the environmental, social and corporate governance dimension of capital flows. From a climate action perspective, the focus naturally rests on investments’ environmental aspects and is commonly referred to under the term “green finance”.

Green Finance Glossary

Asset management - The handling of financial investments by a professional agent

Best-in-class – Investment strategy that opts for funding leaders in given rankings in industries, technologies or categories

Carbon disclosure - Publication of climate-related activities by companies; spearheaded by NGO Carbon Disclosure Project and its disclosure leadership index

Corporate governance - The compliance of a company with laws, guidelines, voluntary agreements and other norms in its business conduct

Divestment – Withdrawal of capital from funds, equity or other capital assets from certain businesses or fields of operation, such as the coal industry

ESG –The Environmental, Social and company Governance dimension of business activities

ESG-Integration – The explicit inclusion of ESG-criteria in traditional risk analysis

Engagement – Long-term dialogue with invested companies to adapt investment decisions to ESG considerations

Exclusion criteria – Systematic elimination of certain investments or other categories, like companies or states, if they fail to abide by certain standard practices

Green Bonds – Bonds issued with the condition to finance environmentally friendly projects

GRI Standards - Globally used standard for sustainability reporting in finance launched by the Global Reporting Initiative Framework (GRI) since 1997

Impact investment – Investments made with the aim to make financial gains while also deliberately influencing ecologic and social developments

Integrated reporting - The inclusion of environmental and social impact information in company reporting to indicate financial and non-financial business aspects in parallel

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) - Screening of funds to exclude companies which generate a given share of their revenue with activities conflicting with given environmental, social or ethical values

Sustainability-themed funds – Financing of business areas or other assets that are associated with sustainability and have a connection to ESG-criteria

Norms-based screening – Evaluation of investments according to given international standards, such as the UN Global Compact, OECD guidelines or others