Political uncertainty weighs heavily on energy policy crunch time year for Germany

Factsheets

- Germany’s coal exit commission

- Germany’s energy consumption and power mix in charts

- What German households pay for electricity

- What business thinks of the energy transition

- Solar power in Germany – output, business & perspectives

- German onshore wind power – output, business and perspectives

- German offshore wind power - output, business and perspectives

- Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions and energy transition targets

- Germany, EU remain heavily dependent on imported fossil fuels

- How much does Germany’s energy transition cost?

- The task force in charge of steering Germany to clean mobility

Government stability

Germany’s 2019 energy and climate agenda is full to bursting. After a lacklustre 2018, the country faces crucial decisions on how to phase out coal, and how to clean up other sectors – notably transport and buildings. In response to the already obvious failure to reach 2020 climate targets, the government plans to make the pending compromises legally binding in its much-anticipated Climate Action Law to get Germany firmly on track for its ambitious 2030 climate goals. Germany's environment minister Svenja Schulze has said she wants the law to be sent to parliament by mid-2019 and have it passed still before the end of the year.

On the economic side, a business community that has become increasingly nervous about recent government inaction appears increasingly keen to embrace the challenges required by Germany’s energy transition. Policymaking needs to catch up urgently in many areas to create the necessary long-term planning security. Andreas Kuhlmann, head of the German Energy Agency (dena), said the conditions for resolute climate action are in fact all present in Germany. And 2019 will show “how serious we’re going to be about it”.

But many policy experts wonder whether Chancellor Angela Merkel’s last government before she leaves office is stable enough to make the required headway. The government coalition has already faced several existential crises in the past months, and its future looks uncertain. The recent leadership vote in which the Chancellor's confidante Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer succeeded Merkel at the helm of her conservative CDU party has revealed deep splits within the country's biggest party.

Meanwhile, the government coalition partner, the Social Democrats (SPD), are still reeling from a string of disastrous state election results. Due to widespread discontent among the SPD’s rank and file over the renewed coalition with Merkel’s conservatives, the party leadership vowed to review its participation in the government at the coalition’s “half time” next autumn.

“The current government is weak and fragile,” said energy policy researcher Claudia Kemfert of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW). “Should it be further weakened, it will become more difficult to consistently implement climate protection policy.”

But according to Carsten Rolle, who heads Germany’s World Energy Council Committee, hope is not lost that the government might increase its capacity to act. “If Kramp-Karrenbauer manages to unite the conservative party […], then it’s possible that the coalition will become more solid than has appeared to be the case over the past few months – we’ve had enough crises indeed.” A development along those lines might also squash ongoing speculations about early elections with a highly uncertain outcome. “I wouldn’t bet my money on new elections within the next 12 months,” said Rolle. “There could be a renewed interest in getting back to serious government work.”

An early ray of hope for more productive government was the appointment by 1 February of Andreas Feicht as new state secretary for energy by economy minister Peter Altmaier. For almost an entire year, the vacant position with key Energiewende competencies made energy policymaking more difficult and made the minister a target for mockery.

However, more determined energy policy and climate action is at risk of being overshadowed by elections in three eastern German states, including lignite mining regions Brandenburg and Sachsen in September, followed by neighbouring Thuringia in October. Attention will mainly focus on the performance of the right-wing nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD), which says climate change is not an urgent problem at all and wants to pull Germany out of the Paris Climate Agreement. The elections will also be a crucial test for the Green Party, which despite spectacular gains in state elections in western Germany in 2018 has yet to prove that it can also become a major player in the eastern states as well.

Preview2019 interview series

German Energy Agency (dena): Conditions for Energiewende success all set

World Energy Council: Gas will loom large on Energiewende agenda

Economist Kemfert: Govt too "weak" for speedy coal exit

Greenpeace: Climate Action Law “crucial” step

Renewable Energy Association (BEE): Coal exit will not be enough for Germany

Association of SMEs (BVMW): Govt must urgently clarify 2030 climate strategy

WWF: German govt must act on environment to retain votes

Consultancy Aurora ER: Expect the German coal debate to continue

Economist Frondel: Coal exit should be driven by markets, is bad for energy security

Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND): Germany's energy policy will change substantially

Coal exit commission

The work of Germany’s coal exit commission has dominated headlines in the country many times in 2018 and will continue to rank high on the agenda in 2019 as well. The task force postponed its last meeting to 1 February. After that, it will propose when and how Germany can end coal-fired power production while at the same time preserving economic stability in mining regions.

Experts are split over the question of whether the commission can deliver a result that is satisfactory for all parties involved. Energy economist Kemfert, for example, believes the task force is too heavily influenced by political interests to set the right priorities. “Regardless of what it ultimately recommends, it will only be a recommendation and what policymakers decide to do with it is completely open,” she said.

On the other hand, dena head Kuhlmann said that the commission will likely come up with useful results. “But it will certainly not be able to tell us in detail how all of this can be implemented,” Kuhlmann says. The “actual work” on Germany’s coal exit can only start when the commission’s report has been put on the table, he added.

Indeed, a lively debate on Germany’s relationship with coal is set to follow the commission’s final report, irrespective of the final end date for coal-fired power production that its members agree on. Regional politicians from coal mining areas in both western and eastern Germany already said they would need billions of euros in state support to manage the phase-out of local coal industries. For energy policy consultancy Aurora ER, the official end date for coal could only be the beginning of a painstaking political bargaining process. "Expect the debate to continue," consultant Hanns Koenig said.

While strictly speaking not part of the coal exit commission’s mandate, an issue that had a major impact on the task force is set to resurface after it had been settled for the time being: in March 2019, energy company RWE and environmental NGO Friends of the Earth (BUND) will meet in court to hear the judges’ verdict on the embattled Hambach Forest in western Germany. However, BUND's Antje von Broock said that while "not all members of the coal commission fully recognise the urgency of the climate crisis, everyone appears to be interested in achieving a result supported by all parties."

Transport & Buildings

Transport is next in line for decisions on how to steer towards carbon neutrality. The corresponding task force will present its proposals by spring on how to align the sector with national 2030 climate targets. Chancellor Angela Merkel has called transport the “problem child” of the energy transition because carmaker nation Germany is struggling to clean up the sector. Emissions have remained roughly unchanged for decades as efficiency gains were eaten up by increasing traffic volumes and a trend to heavier vehicles.

There is some hope the transition is about to begin in earnest, however, as carmakers BMW, Daimler and VW have announced ambitious steps to enter the era of electric mobility. Several mass-market electric models by German manufacturers will hit the roads in 2019 or in early 2020, fuelling expectations that the share of zero-carbon vehicles of new car registrations is about to finally take off. This trend might get a further boost from ongoing debates and lawsuits about diesel driving bans in German cities, many of which will take effect in early 2019.

In addition to the coal and transport commissions, Germany will also get a buildings commission in early 2019 to work out ways how to speed up lagging cuts in heating emissions, which will need to be cut substantially in the next decade to bring the sector anywhere close to its necessary contribution to national climate goals.

Climate Action Law

The proposals from all three commissions will feed into the much-anticipated Climate Action Law that environment minister Svenja Schulze has promised for 2019. It will likely be the single most important item on the agenda for Germany’s climate and energy policy in 2019, and perhaps even for the years to come.

“This act has to ensure that not only the energy sector but also transport and agriculture meet their 2030 targets after decades of not delivering anything in terms of carbon reduction,” Greenpeace head Jennifer Morgan told Clean Energy Wire. The environmental activist said the new law has to be more than “a mere legislative frame.” Each sector needs to spell out the steps intended to reach climate targets already laid down in Germany’s Climate Action Plan 2050.

According to Germany’s chief climate diplomat Karsten Sach, the ministries will devise individual emission reduction plans for each sector and will merge their drafts in early 2019. Before the law can be adopted later that year, the government will debate how progress in each sector can be monitored and, in case of non-compliance, how the targets can be made binding. “There will have to be consequences for sectors that do not meet their targets,” Sach said.

The Climate Action Law then serves to ensure that these measures are legally binding. “Otherwise Germany will lose more time - and credibility,” Greenpeace head Morgan said. The consolidated document will also outline how the German plans fits into the EU climate strategy.

CO2 price

Yet, many observers are convinced that making CO2 reduction plans for each sector alone will not suffice in making the Climate Action Law a powerful climate action tool. “A key premise for Germany to meet its climate goals is a strong CO2 price signal,” said energy economist Manuel Frondel of research institute RWI Essen. While a carbon price could only unfold its full potential when it is adopted internationally, a “price signal” could already be established by each country on its own, for example by setting a minimum price or by introducing a CO2 tax, he added.

The idea of a national CO2 price as a booster for cost-efficient climate action is not confined to the academic world. While it had led to internal government quarrels between Germany’s environment minister Schulze and her colleagues from the ministries for finance and for economy and energy in late 2018, many companies in the country as well as Germany’s Court of Auditors have started to endorse the concept as well.

Regardless of political agreements on a national carbon price, however, a further increase in the European Emissions Trading System’s (ETS) CO2 price could increase the pressure to reduce industry emissions anyway.

Other things to watch out for…

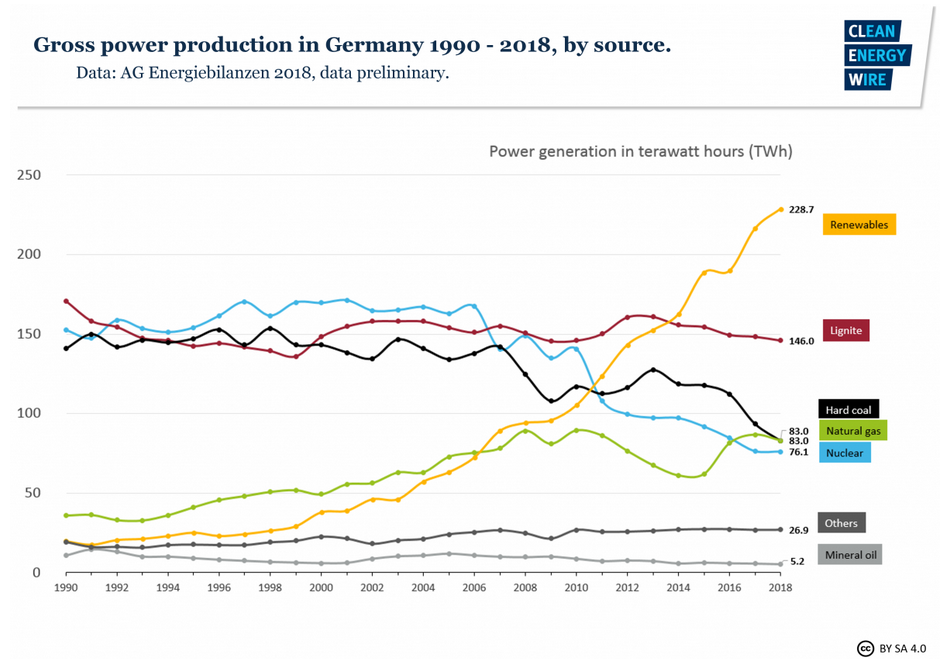

Although not poised for any major policy decisions in 2019, the expansion of renewable energy sources remains an issue that is set to emerge time and again in Germany. The two most important renewable sources in Germany’s energy transition, wind and solar power, face an important year in terms of sales figures.

Wind power lobby group BWE warns that a trend towards slower expansion that already begun in 2018 could intensify in the following year. Although the government has provided some relief by allowing additional onshore wind power auctions starting this year, the BWE said that faulty auction design for previous auctions still means the sector might face a cliff in the near future.

For Germany’s solar power sector, a decisive feature of the year will be the impact of Chinese solar panels on the European market, after the EU lifted tariffs on them in September 2018. While German panel producers fear the new trade regime will finally pull the plug on their business, other companies active in the sector hope the removed tariffs mean lower prices and, consequently, a boost in expansion.

Regardless of the expansion in different renewable power industries, the expansion of Germany’s power grid will be an important topic in 2019 as well. While economy and energy minister Altmaier made grid expansion a key feature of its first year in office, the new government in Bavaria as well as governments and citizen initiatives in other states already signalled they will give the minister a hard time to get the much-needed energy transition infrastructure in place.

Last not least, the German energy industry will see the end of a major reshuffling that accelerated in 2018 when the country’s two biggest energy companies, E.ON and RWE, announced they would swap significant parts of their assets, with E.ON focussing on energy retailing and RWE on generation. The landmark deal so far has been carried out without creating a lot of noise and is set to come to an end in 2019.