Must Germans give up sausage and schnitzel to cut agri-food emissions?

The German agriculture minister called the 2018 summer drought a “weather event of a national scale”. To farmers, this means millions of euros in crop losses and the risk they might not be able to sustain their herds through the winter. To climate activists it is a unique opportunity to reduce Germany’s livestock numbers. “This would benefit both the climate and animal welfare, because the remaining cows and pigs will have more space,” Reinhild Benning, Senior Advisor for Agriculture and Livestock at Germanwatch at NGO Germanwatch, told the Clean Energy Wire.

Animal farming is one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases in Germany’s agriculture sector. Emissions from farming amount to seven percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions; of these, 37.5 percent (24.5 million CO2 equivalents in 2016) come directly from methane emissions of animals farmed in Germany, mostly from cattle and dairy cows. Although other livestock such as swine and poultry don’t emit as much directly (unlike cows they aren’t ruminants and don’t emit much methane), they also cause emissions through their feeding needs (land-use), barn emissions and manure.

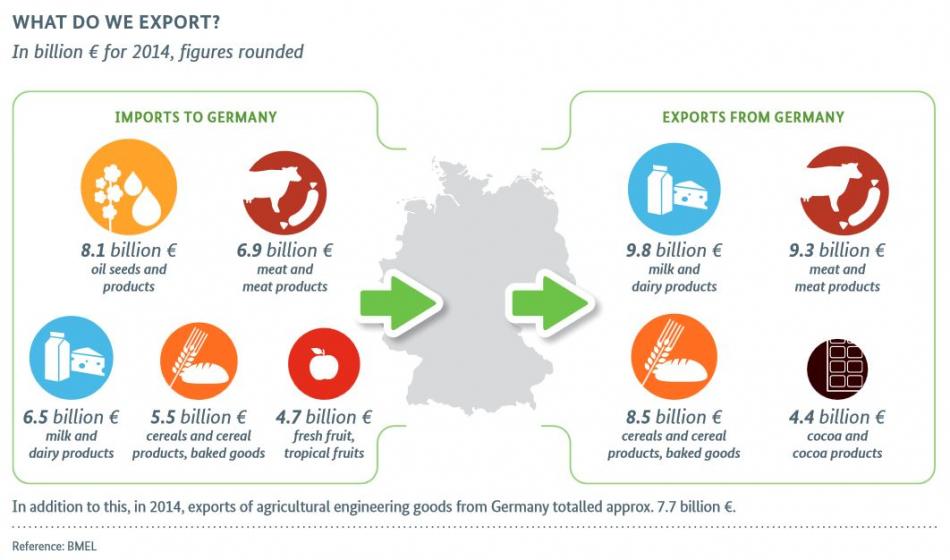

The production of milk and meat is a 27-billion-euro business in Germany (2017). Of the 321,600 farms in Germany, 67 percent hold animals. Germany exported milk, dairy and meat products worth 17 billion euros in 2016.

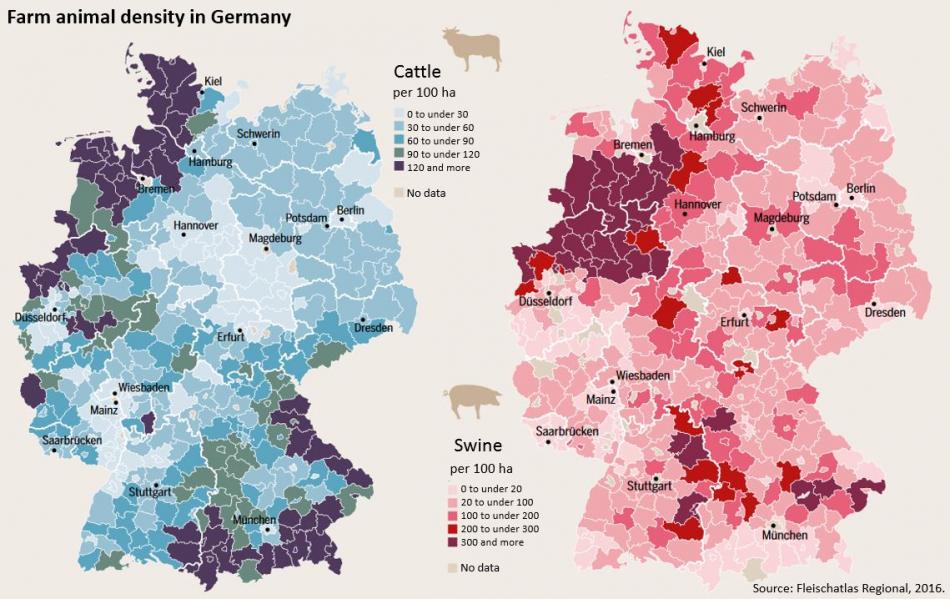

Germany still has a large share of milk and meat farmers with small- and medium-sized operations (1-99 cattle or cows) who also cultivate their own fodder. But over 72 percent of all cattle and 52 percent of milk cows are held on farms with more than 100 animals. While the number of livestock farms has decreased by between 7 (cattle) and 20 (sows) percent between 2013 and 2016, the average size of the livestock herds has increased – and with it concerns about animal welfare and the environmental impact of a high concentration of farms in some regions.

Source: Fleischatlas 2016.

NGOs and even the German government in one of the early drafts of the Climate Action Plan 2050, have said that reducing the overall number of farm animals in Germany would make a viable contribution to emission reductions from the farming sector.

The 2018 drought summer could be a step towards achieving this, environmentalists say.

“The slaughter houses are full”

Because feed crops like maize and grass (hay) have experienced such bad harvests this year, many farmers used up their winter fodder early. As a consequence, livestock owners will have to reduce the size of their herds if they don’t want to pay high prices for fodder due to scarcity later in the year.

“The slaughter houses are full,” Friedrich Ostendorff, MP for the Green Party in the federal parliament and organic farmer with 150 pigs and 60 cattle near one of the most intensively farmed regions of Germany in North Rhine-Westphalia, says.

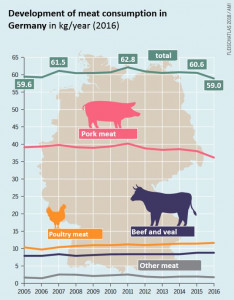

Although German consumers are often reputed to love sausages and other meat products, they in fact have displayed a declining interest in animal products. Meat consumption fell below 60 kg per person in 2016, after being consistently above that level for the previous 10 years. Germans eat 59.7 kilogrammes of meat per head a year, compared to 98 kg in the US, 50 kg in China and 3.2 kg in India, according to 2017 figures.

In the 2013 federal election year the Green Party were heavily criticised for their “Veggie Day” campaign – a proposal that public canteens should serve no meat once a week. Some even blamed the Green Party’s lower 2013 election results on the anti-meat campaign, which has made the subject a political taboo for many since.

“Until now, both farmers’ organisations and politicians have shied away from participating in this debate,” Harald Grethe professor for International Agricultural Trade and Development at the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin and chairman of the Scientific Advisory Board on Agricultural Policy, Food and Consumer Health Protection (WBAE), says.

The German Nutrition Society (DGE) suggests a meat intake of 300-600 grammes per week and the WBAE calculates that following this advice could reduce Germany’s emissions by up to 22 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents per year.

But the German Farmers’ Association DBV, influential representative of the country’s 380,000 farmers with revenues of 40 billion euros per year, has a different plan. Backed up by the final version of the Climate Action Plan 2050 – which doesn’t mention reducing cattle in Germany – lower emissions from livestock farming are to be achieved mainly through efficiency gains and voluntary best practice rules.

“It’s not an option to get rid of animal husbandry,” Bernhard Krüsken, secretary general at the DBV said in July.

“It is not a successful strategy to patronise German consumers and tell them to change their preferences when it comes to meat-eating,” Steffen Pingen, head of the environment department at the DBV says. “We are pursuing the goal of producing agricultural products as climate-efficiently as possible”.

The farmer’s association suggests other measures to reduce methane emissions from ruminants. Among these are breeding cattle that emit less methane, adjusting feeding and rearing methods and increasing the health and lifespan of milk cows, as the longer a cow lives and gives milk, the more efficient it becomes from an emissions perspective. Both the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have published similar advice.

“Portraying cows generally as climate killers is nonsense”

By optimising the feeding of cattle, methane emissions from their digestive system could be reduced by 10 to 15 percent, says Cornelia Metges, professor and head of the Institute of Nutritional Physiology at Leibniz Institute for Farm Animal Biology (FBN) in Dummerstorf.

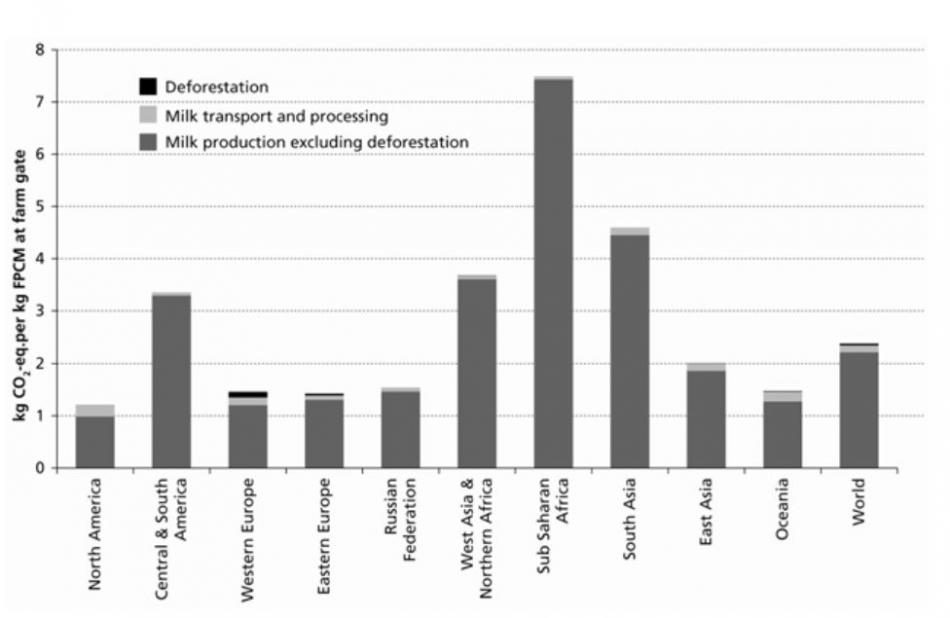

The farmers’ association says that the best climate protection effects can be achieved with cattle held in barns, because feeding can be easily controlled and it is possible to maximise the use of protein-rich concentrate in their diet. They also say dairy products from Germany have a smaller carbon footprint to those from most other parts of the earth.

Source: Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Dairy Sector, FAO 2010.

There are conflicts of interest between animal welfare and climate friendly livestock management. Some environmentalists promote animal rearing in which cattle are held mainly outside in fields, but farmers point out that this increases their intake of grass and thus creates more emissions that are bad for the climate. Animal welfare activists also favour barns with open walls and outdoor spaces for pigs and chickens, but closed structures with air purification systems would be better equipped to filter out ammonia emissions.

A middle ground will have to be found, professor Metges says. Cows emit more methane when they eat old and hard grasses, yet in order to give milk and stay healthy, they also need at least 45 percent fibrous fodder (like grasses, silages and hay). A climate-optimised diet could be implemented both in the barn or on pasture, Metges says, if the right combination of concentrate and and good quality forage feed such as grasses were used. “Calling cows per se ‘climate killers’ is nonsense,” she says.

Could less agriculture trade benefit the climate?

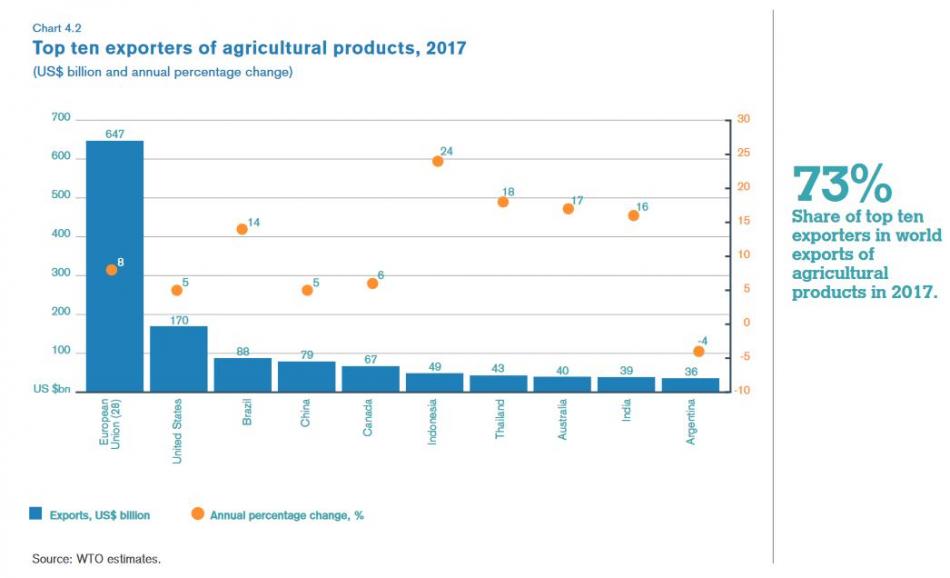

Germany is both the world’s third largest exporter and importer of agriculture products, according to 2015 WTO figures. Ever since the year 2000 exports and imports have grown continuously. One third of Germany’s farming products are exported. According to calculations by consultancies adelphi and systain, Germany is now using some 22 million hectares of land globally for its food retail trade.

In German supermarkets, exotic foods are available year-round and from all over the world. Mangos flown in from India, Nile perch from Lake Victoria and beans and asparagus from Peru. Although only one percent of groceries are flown in to Germany, they cause 16 percent of all emissions from food transport. Environmentalists say customers should avoid produce transported by air and say that eating regional and seasonal food would save emissions. The WBAE has calculated that an 80 percent reduction in air transport of groceries to Germany could save 0.7-1.7 million tonnes of CO2 per year.

While the scientists don’t see much savings potential in eating regionally produced food (because it depends on the means of transport used and the efficiency of production), they advocate – just like the government, the farmers’ association and environmentalists – the prevention of food waste. This could save some 3-9 million tonnes of CO2, simply because less food would have to be produced if less were wasted. According to the Climate Action Plan 2050, the government wants to reduce food waste by half by 2030.

But although everyone is on board when it comes to curbing food production (and thereby farmers’ income) if less food is wasted by consumers, telling the same consumers to eat less meat or advocating a reduction in meat exports, is a red line for farmers and the agriculture ministry.

“The decision to promote an agricultural economy that is competitive on the global market, so that Chinese people buy German meat, was wrong from my point of view,” said Germany’s then-environment minister Barbara Hendricks in 2016. “German agriculture makes about 15 percent of its turnover on the world market, the profits are distributed among a few, but we all pay the price.”

When Hendrick’s ministry made up some satirical farmers’ almanac sayings as part of a campaign to highlight the problems of too intensive livestock farming in 2017, farmers were not amused. Instead of the intended light-hearted nudge to get farmers to change their habits, the farmers instead felt parodied and belittled and said that the environment ministry must be running out of good arguments if it had to resort to such childsplay.

German farmers produce more meat than people in the country can eat. The overall self-supply with beef in Germany is on average 108 percent (2013-2015), 118 percent for pork and 125 percent for milk products.

Around 27 percent of the raw protein needed for German farm animals is covered by soy bean products, of which 75 percent are imported, mostly from South America, the agriculture ministry reports. Between 1997 and 2018, global land use for growing soy beans has increased from 67 million hectares to almost 130 million hectares. In 2010 Germany was indirectly using some 6.4 million hectares abroad to feed its livestock.

If the amount of meat produced matched Germans consumption and if the country (like for example Sweden) would label clearly whether meat is locally produced under animal- and climate-friendly conditions, emissions from domestic animals could be reduced and farmers would receive higher prices for their products, Germanwatch says. “German meat consumption is falling and both arable land and labour are so much more expensive in Germany that only a high-price strategy will work in this sector,” Benning argues.

The farmers’ association DBV however, disagrees. “No German farmer specifically produces for the export market,” says Steffen Pingen. “But at the same time the world market for food and farming goods is a fact and obviously we have to have competitive products.”

Meanwhile, the ministry for agriculture is pursuing a pro-export strategy with the aim of “helping mostly small- and medium-sized companies in the German farming and food business to get access to foreign markets.” The ministry’s export-support programme had a volume of 8.8 million euros in 2017.

Such intensive farming and animal husbandry methods are exactly what most environmentalists oppose. “It’s a naïve miscalculation if high harvest outcomes are equalled with better carbon footprints, if this mass production needs high inputs and is not needed for local consumption, but suppresses local production elsewhere and causes additional transport emissions,” Benning from Germanwatch says.

International agriculture trade professor Grethe says that in the end domestic consumption is the more important lever when curbing emissions from farming – not the export or import strategy. “We have to consider that the food Germany no longer exports has to be grown elsewhere, which could result in overall higher emissions. But of course if Germans were to change to a more sustainable diet, it would be possible to farm the existing arable land less intensively and therefore in a more climate friendly manner.”

NGOs like Germanwatch and NABU maintain that animal fodder imports to Germany should be curbed and argue that it would be better for developing countries, ecosystems, animals and the climate if farmers in Germany produced their own leguminous plants (e.g. beans, peas, lentils, lupins and soy beans) for animal feeding purposes.