Bavarian vote shakes Berlin coalition, leaves energy policy in limbo

Voters have delivered a political earthquake in the prosperous German state of Bavaria, which cost the conservative Christian Social Union (CSU) its absolute majority and made the Greens the second-largest political force in southern Germany.

The consequences for national politics are far from certain but potentially significant. A weakened CSU could shift powers within the party’s conservative alliance with Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU). Should individual politicians like CSU leader Horst Seehofer decide to take responsibility for the disastrous results and step down or be ousted by his party, a major re-shuffle of federal cabinet positions would be in order.

Some analysts see the dramatic losses for the Social Democratic Party (SPD) as an equally important aspect of the election results. These could further destabilise the alliance and even the break-up of Merkel’s grand coalition government of CDU, CSU and the Social Democrats, according to commentators.

“Watch as the pressure rises on SPD boss Andrea Nahles to break the pact,” wrote Andreas Kluth in an opinion piece for Handelsblatt Global. As Merkel’s hold on power “continues to become weaker”, the Social Democrats might be “the first link to break”, he wrote.

“The grand coalition is under a lot of pressure,” the SPD’s general secretary Lars Klingbeil told public broadcaster ARD in an interview. “We are now facing very decisive months.”

The uncertainty comes at a time when the coal commission, which the government has put in charge of finding a pathway out of coal-fired power generation, is due to present first results. The government also plans to pass a climate protection law in 2019 in order to guarantee that the country of the Energiewende meets its 2030 emissions reduction targets. After already postponing the 2020 climate target, the government is also under pressure to find a lasting solution for the emissions from cars, as the diesel scandal continues to cause negative headlines.

In any case, analysts and opposition politicians do not see the recent standstill in energy and climate policy on the national level vanish any time soon. Anton Hofreiter, head of the Green Group in federal parliament (Bundestag) said the results in Bavaria made him worry about Angela Merkel’s cabinet’s ability to govern. “I don't expect the dispute [in the grand coalition] to end,” he told Süddeutsche Zeitung. “On the contrary: CDU, CSU and SPD will only act more nervously, and thus the blockades will become even bigger.” The government does not have the strength to tackle urgent issues like climate change, said Hofreiter.

[Also read the CLEW election preview Shake-up in Bavaria's election may impact German energy policy and the factsheet Facts on the German state elections in Bavaria.]

Uncertain future for energy policy as conservative Bavarian coalition likely

In Bavaria, meanwhile, the CSU – sister party of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s ruling Christian Democrats (CDU) – is set to continue to govern the prosperous state, but it will need a coalition partner.

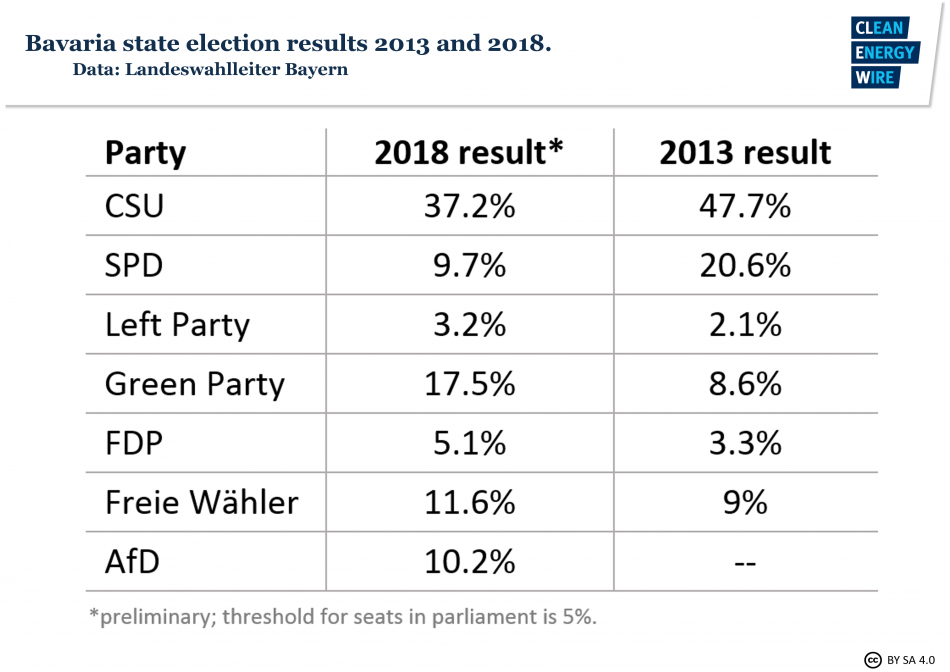

The CSU saw its worst election result since 1950 with 37.2 percent of the vote, according to preliminary results, while the Green Party won 17.5 percent. The Social Democrats (SPD) dropped dramatically to 9.7 percent since the last elections in 2013, and the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) won 10.2 percent.

In an interview with public broadcaster ZDF, state premier Markus Söder (CSU) said he would “clearly prefer” a coalition with the conservative Free Voters, which won 11.6 percent of the vote. The Free Voters have not been in the state government before and their participation’s impact on Bavarian energy policy is hard to gauge. It will depend a lot on how well the party positions itself as a junior partner to a party that has governed Bavaria by itself for most of the past 65 years.

According to the newspaper Merkur, the Free Voters see themselves as representing the political centre, largely focussing on strengthening municipal politics, for example increasing local power generation. At a press conference after the election, Free Voters’ head Hubert Aiwanger presented the party’s core demands ahead of possible coalition talks, including “progress regarding the energy transition”, but focussing more on topics such as free daycare, or the rejection of a third runway at the Munich airport.

In an interview with public radio broadcaster Deutschlandfunk, Aiwanger said his party’s energy and climate policy would be less “ideology”-driven than that of the Green Party. “We will make very concrete and realistic progress in the energy transition,” he said. In line with his party’s election programme, which calls for an exit from fossil energy sources as fast as possible while increasing regional energy supply, Aiwanger also said the Free Voters oppose SüdLink, the planned major high-voltage power transmission line, which is meant to bring wind power to Germany's industrial south.

Greens win big, but programme “hardly coalition-compatible”

Despite huge gains in Bavaria, a coalition between the CSU and the Green Party is seen as unlikely, given the conservative alternative. “The Greens’ programme is hardly coalition-compatible,” said Söder.

Aside from winning six direct seats for the state parliament, the Green Party also gained the majority in Bavaria’s capital Munich for the first time.

"The Greens achieved a historic performance in Bavaria, because they attracted almost as many votes from CSU (200,000) as from SPD (210,000),” energy analyst and expert on the Greens Arne Jungjohann told Deutsche Welle. “The CSU strategy of fishing for right-wing voters backfired as it lost most of its voters to the Green Party." The CSU had taken a tougher stance on immigration to prevent Bavarians from voting for the AfD.

In an interview with public broadcaster ARD, North Rhine-Westphalia’s state premier Armin Laschet (CDU) presented a similar argument. “Our real competitor now is the Green Party,” said Laschet.

On Sunday (14 October), the Greens gained electoral successes not only in Bavaria, but also in Belgium and Luxembourg. This "rise of the Greens", as Claire Stam writes on EurActive, is not to be confused with a shifting majority within the left-wing political spectrum. Instead, it shows that the traditional left-right political divide is getting outdated, European Greens co-chair Reinhard Bütikofer told EurActive in an interview.