Norway bets on gas and CCS to complement Europe’s energy transition

[Note: On 31 August 2018, Norway’s Conservative Prime Minister Erna Solberg replaced her minister for oil and energy in a cabinet reshuffle. Terje Søviknes has been discharged from his office.]

“To be a battery for all of Europe? That will never be possible. We are huge on energy, but not that huge.” Terje Søviknes chuckles. When the Minister of Petroleum and Energy sits down with a group of journalists from Germany in his Oslo office in June 2018, drier-than-normal weather and unseasonably high temperatures over many weeks have depleted Norway’s hydro power. Over the following months, record low stocks in reservoirs will lift power prices to new multi-year highs and trigger electricity imports from neighbouring countries.

While supply security for the coming winter is not at risk in the country that produces about 96 percent of its electricity from hydro energy, according to the water resources and energy directorate (NVE), its role as a steady electricity supplier for Denmark, Sweden and others might be.

The journalists’ meeting with the minister is an early stop on a two-day government-organised press tour entitled “Norway´s contribution to the German energy shift”. For years, the European Union has focussed on the narrative of the Scandinavian country as “Europe’s green battery”. The idea is that steady hydro power can be used to supply neighbouring countries at times of low wind yield.

What’s more, pumped storage facilities could take in excess renewable electricity on windy days in northern Europe, store the energy over various time horizons and send it back through interconnectors like Nordlink, the German-Norwegian power link currently under construction in the North Sea. German politicians have hailed the project as the key to making the German Energiewende a European project.

Germany’s energy transition – decarbonising the economy without relying on nuclear power – began as a isolated expedition of rapid renewables expansion more than 20 years ago. Today, the current European Commission has made completing the Energy Union one of its priorities. Its aim is to facilitate “the transition to a low-carbon, secure, and competitive economy”. While much remains to be done, joint energy and climate goals already set the framework for a future, interconnected, internal energy market in which countries step in to help each other out when supply falls short.

Quick facts on Norway’s energy system

- 3rd largest exporter of natural gas in the world (behind Russia & Qatar), but produces only 2% of global crude oil demand

- Nearly all oil & gas produced on the Norwegian shelf is exported

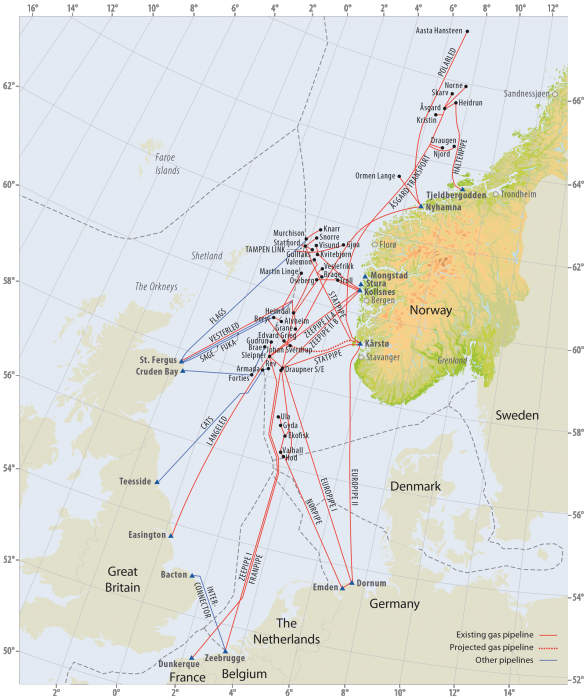

- 95% gas exports go to Europe via pipelines, 5% exported as LNG

- Norwegian gas provides about 25 % of the EU's gas demand, Germany biggest customer

- oil and gas equals about half of the total value of Norwegian exports of goods at about 45 billion euros in 2017

- about 1/3 of the Norway’s estimated gas resources have been produced so far

- total length of gas pipeline network: 8,800 kilometres

- About 97% of electricity produced by hydropower plants

- 1,550 hydropower plants; 1,000 storage reservoirs (half of Europe’s reservoir storage capacity)

- Norway has highest share of electricity produced from renewable sources in Europe

In his meeting with the journalists, Norway’s energy minister dampens expectations of direct electricity flows: “It’s important that we can offer flexibility through the interconnectors, but of course there are also limitations,” says Søviknes. For him, Norway’s large reservoirs of natural gas are “more important” when it comes to balancing the power systems and securing Europe’s energy supply during its transition to a low-carbon economy. Søvikne’s arguments are in line with those of the German gas industry, which presents the fossil fuel as a clean alternative to oil and coal in power production, heating and transport. [Read the full story in the CLEW dossier Industry bets on gas as last trump card in Energiewende]

Reversing the flow

Norway is the third largest gas exporter in the world and sells nearly all of it on the European market. In 2017, four decades after Norwegian gas exports began, the country’s gas grid operators transported a record 117.4 billion standard cubic metres to continental Europe and the UK. Germany receives up to a third of its gas imports from Norway.

As the world starts switching from fossil fuels to renewables, Norway is setting its sights on a different business model. The country has exported vast amounts of carbon in the form of crude oil and natural gas since the 1970s, helping it build up billions of euros in its sovereign wealth fund – the Government Pension Fund Global. Now it’s offering to take back the carbon – at a price.

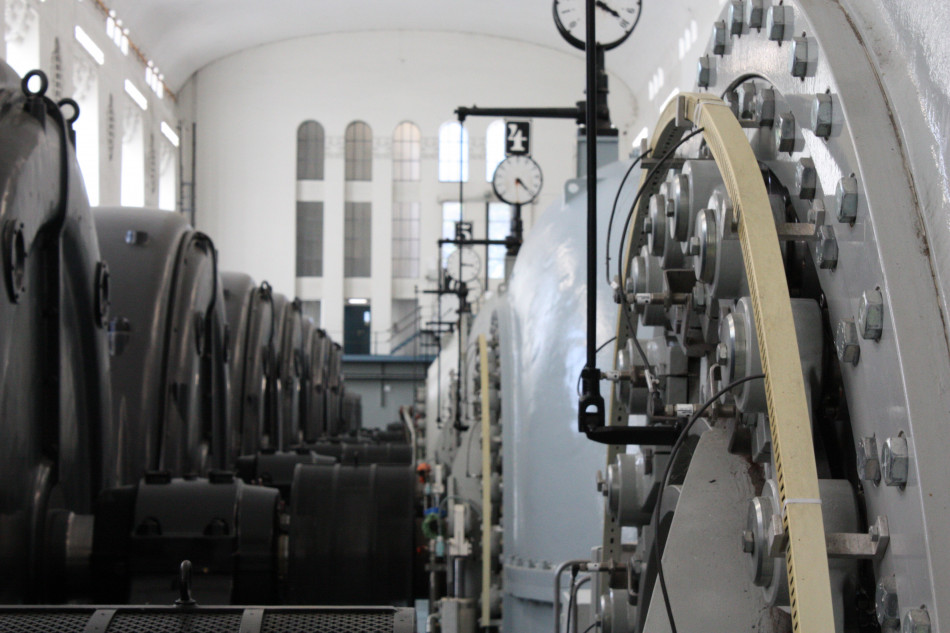

The enormity of Norway’s gas operation is apparent at Kårstø. Europe’s biggest processing plant is a labyrinth of pipes, flare towers and tanks on the North Sea coast, just 40 kilometres north of the country’s third largest city Stavanger. It is connected to Norway’s extensive 8,800-kilometre network of subsea pipelines, which links about 50 active offshore gas fields and onshore terminals directly to countries in continental Europe and the UK.

Here, Tor Martin Anfinnsen lays out Norway’s vision for the future. Anfinnsen is Senior Vice President Marketing and Supply at Equinor, the largely state-owned oil and gas company formerly known as Statoil. In his view, the solution to Europe’s difficulties in reaching climate targets is capturing the CO₂ that is emitted when burning or using natural gas, sending it to Norway and storing it 1,000-2,000 metres below the North Sea bed – where the gas came from in the first place. Ideally, large parts of today’s infrastructure could be used after some refitting to transport the CO₂.

“The storage possibilities off our coasts are practically unlimited,” Anfinnsen tells one journalist. “We could store all European emissions for hundreds of years.”

Scientists increasingly see carbon capture and storage (CCS) as vital to keeping global warming well below two degrees Celsius – but it is expensive, as Norway experienced in 2013. After escalating costs and a change of political leadership, the Norwegian government dropped first plans for the development of full-scale carbon dioxide capture, putting an end to the project former Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg had called Norway's "Moon Landing".

Now, the Norwegian government is giving CCS another go. It wants to set up a full-scale demonstration project to show the technology’s feasibility on an industrial scale from capture, via transport to storage – called “Northern Lights”. Whereas the last project focussed on capturing carbon emissions from fossil power plants – which would in theory make it possible to keep these running even in times of ever-stricter climate targets – oil and energy minister Søviknes explains his adapted approach:

“Now, we’re focussing on the industrial sector, because here we have no other option,” he says. “There are unavoidable CO₂ emissions as part of the industrial processes.” Søviknes hopes that this shift makes investments by other European countries more likely.

“Investment and operational costs during the test period may be between 1 and 1.5 billion euros, and of course that’s a lot of money for just one country. We are seeking cooperation especially when it comes to the European Union.” The Norwegian government has emphasised the importance of including CCS in the EU’s relevant support mechanisms, for example the Innovation fund.

“Yes, projects in Norway will be eligible as Norway is a member of the European Economic Area and therefore part of the EU Emissions Trading System,” Anna-Kaisa Itkonen, spokesperson of the European Commission told the Clean Energy Wire.

The European Union acknowledges the role of CCS in reaching the EU's long-term emissions-reduction goals. The Innovation Fund is currently being developed to be set up as part of the post-2021 reform of the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) to help the EU reach its 2030 climate goals. The fund will support low-carbon innovation in energy intensive industry, carbon capture and utilisation (CCU) technologies, innovative renewable energy and energy storage technologies, and demonstration projects on the environmentally safe capture and geological storage of CO₂ – CCS. According to Itkonen, the first call for projects should take place in 2020.

Norway’s goal is to have an investment decision for the demonstration project in 2020 or 2021 and to start operations in 2024. The Norwegian government has not yet approached the European Union with a request for financial support for the CCS project, Itkonen told the Clean Energy Wire.

Norway's plans might be "bigger than necessary" - German NGO

Asked about Northern Lights, a spokesperson of the German economy and energy ministry (BMWi) told the Clean Energy Wire that the government “in general does not comment on other country’s projects” and referred to its own “Climate Action Plan 2050”. In it, the German government says that the industrial sector is particularly challenging in terms of reducing emissions and that CCS “may be necessary” in the long run.

Should Germany decide to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 90-95 percent by 2050 – the upper end of its current official goal corridor – CCS “will very likely be necessary, for example to reduce unavoidable industry emissions,” agrees Jessica Strefler, researcher at The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK).

For the CCS technology to be available in time and sufficient scope, it has to be developed now, says Strefler. “This makes the Norwegian project an important step,” she told the Clean Energy Wire.

For Erika Bellmann, climate and energy expert at the environmental NGO WWF, the basic idea of a CCS project in Norway is “not wrong”, and she calls for a nuanced view. CCS as a way to reach climate targets “should not be demonised”. There are reasonable applications for the technology, but there are limits in scale.

If one assumes a “reasonable climate policy including the introduction of low-carbon processes for industry”, Norway’s plans might be “bigger than necessary”, says Bellmann. “It’s an extremely large-scale project with lots of planned infrastructure, and we’re not sure if the project’s scale is suitable for the amount of remaining emissions in Europe.”

Bellmann also warns of lock-in effects: “Once you’ve built CO₂ pipelines to Norway, you will want to fill them, and not only for the next ten years.” From an economic point of view, Europe would basically “commit to producing carbon emissions” if investors decided to participate in such a capital-intensive and long-lasting endeavour.

Doubts about public acceptance in Germany

Whether or not the German public would accept sending domestic emissions abroad is yet another issue, and could complicate Norway’s search for investors. “We have found it difficult to bring it into the discussion in Germany,” says Equinor’s Anfinnsen.

“At the moment, CCS is off-limits in Germany,” Bellmann told the Clean Energy Wire. After strong public opposition, the country introduced a law in 2012 which gives federal states a veto right regarding carbon storage on their land. According to Bellmann, the debate leading up to the technology’s earlier rejection was misguided. “It did not centre on small amounts of residual emissions in industry, but was essentially about saving coal-fired power generation and the fossil energy industry. That led to many misgivings which cannot be dispelled overnight.”

For citizens to accept Norway as an alternative to carbon storage projects within Germany, a certain “out-of-sight, out-of-mind attitude” would have to prevail. That this would happen is doubtful, says Bellmann. “Citizens here don’t only campaign for sustainable development in Germany, but also beyond national borders. Many would not accept simply pushing the problem to a neighbouring country.”

Other countries’ openness to supporting the CCS project depends on several factors, not least their own energy mix. Sweden’s power supply relies to about 83 percent on hydro and nuclear energy, and there has been little discussion about CCS, as attempts to reduce carbon emissions focus largely on the transport sector. In 2014, Swedish energy giant Vattenfall abandoned its CCS project at German lignite plant Schwarze Pumpe after R&D budget cuts.

Other neighbours seem like the perfect match for Norway. Implementing CCS technology in Finland requires that the captured carbon dioxide is transported abroad for storage, because no geological formations suitable for long-term storage have been found in Finland, according to the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland.

In Denmark, CCS pilot projects have run into resistance from the population, so the Danish government has no intention to permit the onshore CO₂ storage in Denmark at the moment – awaiting positive results from experiences abroad, writes the Global CCS Institute. However, there are Danish projects investigating new methods of carbon storage.

The Norwegian population, meanwhile, has voiced little opposition, likely also because the carbon would not be stored under inhabited land.

“Public opinion on CCS is quite different in Norway,” says oil and energy minister Søviknes with a smile. “We have the storage facility far out in the North Sea below seabed and we have 20 years of experience storing CO₂. It’s not controversial.”

This article was made possible through a 2-day press tour organised by the Norwegian Embassy in Berlin in June 2018. The Clean Energy Wire paid for its own flights and accommodation.

![Capturing CO2 at Klemetsrud combined heat and power [CHP] waste-to-energy plant could be part of Norway's large-scale CCS demonstration project. Photo - Julian Wettengel CLEW 2018. Capturing CO2 at Klemetsrud combined heat and power [CHP] waste-to-energy plant could be part of Norway's large-scale CCS demonstration project. Photo - Julian Wettengel CLEW 2018.](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/article/2018/08/img-3874.jpg?itok=HEZPftFn)