Vote25: Germany must embrace transformation, seek European approach to industry crises – researcher

***Please note, this interview is part of CLEW's 2025 preview series, covering the German national election and relevant climate and energy topics in Europe. Read all interviews here.***

Clean Energy Wire: It has been about two months since the break-up of Germany's coalition government. Has this had any major effect on the country’s role in Europe and the world, especially in the energy sector and on climate policy?

Simone Tagliapietra: While the direct impacts so far might not have been visible, the current political situation in Germany – like the current political situation in France – is certainly having important implications for the development of European energy and climate policy on the one hand, and industrial policy on the other.

This is not surprising. Competitiveness is the key priority of the European Union. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen has put competitiveness at the top of the agenda for the new mandate. A strong new industrial policy is one of the key actions that the new Commission will have to undertake, namely with the proposal of a Clean Industrial Deal in February.

When it comes to energy and industrial policies in Europe, no country is as important as Germany in contributing to defining the priorities. Without a strong Germany, Europe cannot develop strong industrial and energy policies. So, the sooner Germany’s political situation has clarity and stability, the better for EU policy making in this space.

How do you see the German lame duck government influencing this Clean Industrial Deal?

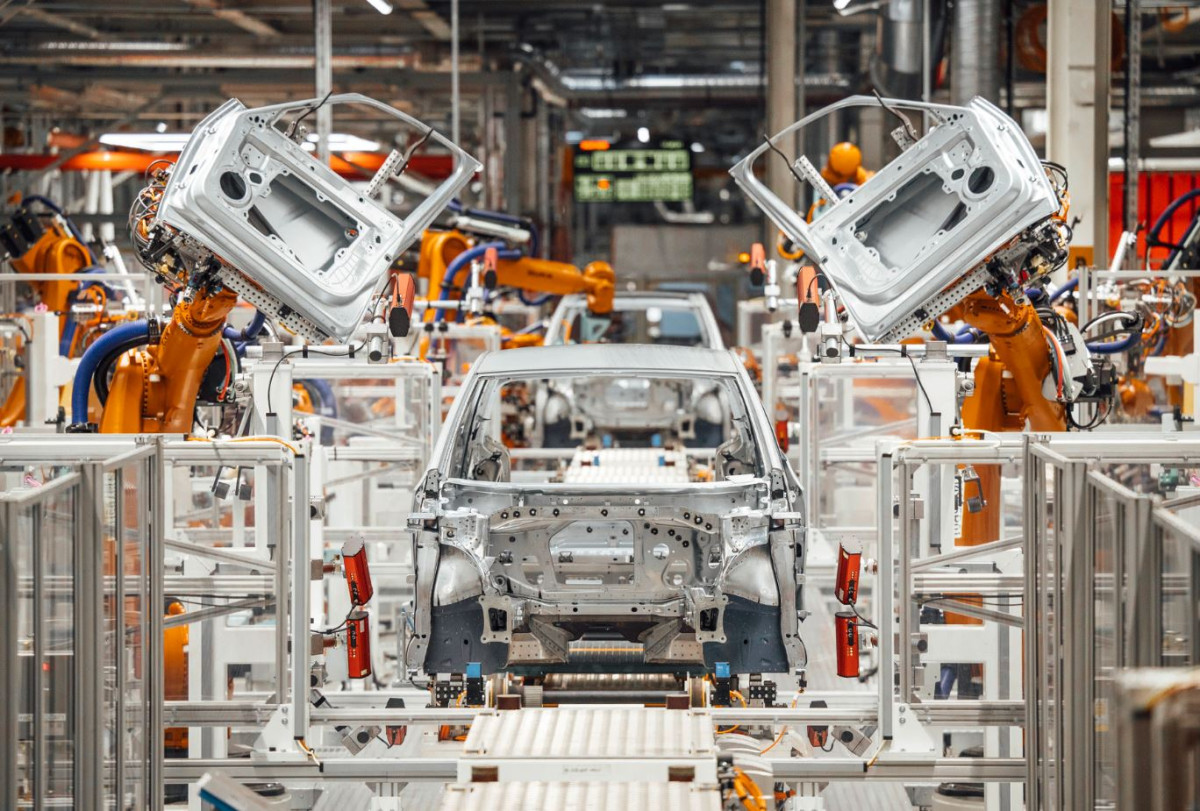

Now is not the time for member states to intervene in this process. The Commission will put forward a bigger policy framework – which will be the communication in February. With that, there will be a more coherent picture of what needs to be done in the coming years to boost European industry, competitiveness in the cleantech space and in energy-intensive industries such as the automotive industry, a key sector for Germany.

In the months and years that follow, regulations and directives will be drafted, which member states will negotiate with the European Parliament, and here the national governments will play a role.

How do you see Germany’s role in the geopolitical context under its next government?

Many of the energy and industrial policy issues we have on the table at the European level find a solution in ‘more Europe’.

Europe, for example, is at a comparative disadvantage with the United States, China, and many others when it comes to energy prices. One way for Europe to structurally lower energy prices – and I would say to lower the cost of the energy transition – is by having a more integrated electricity market. The next German government, like all EU governments, must realise that deepening the Energy Union is in the interest of everyone.

When it comes to industrial policy Europe must base it on both horizontal and vertical actions. Horizontal actions mean the framework conditions for companies to thrive, such as energy prices, and the availability of skills and capital.

However, we also need sector-specific vertical interventions. In the automotive sector, the challenge is to be as European in the approach as possible. Otherwise, we have the usual problem of ending up with a few countries, namely Germany, subsidising a few companies, namely the incumbents in the sector. A national course of action would undermine the Single Market which is not in the interest of Germany. The next government has to understand this.

A revision of the EU state aid framework – which allows countries like Germany to provide state aid in cases where it fits the common European interest – could help.

What about cases where it does not fit the common European interest?

The risk I see in Germany, but also in other countries, is that it subsidises incumbent companies – which might no longer have a comparative advantage or lack the innovative forces which the new market reality requires – with a lot of public money.

The risk is – to quote the former European Central Bank president Mario Draghi – that this would just prolong a sort of ‘slow agony.’ Instead, governments must put the house in order, identify comparative advantages and restructure certain industries. Otherwise, you lose jobs and a lot of public resources.

How should the EU prepare for incoming U.S. president Donald Trump?

The reality we need to face with Trump is increased heated tensions. The extent to which he will actually be willing to match words with real action when it comes to tariffs, for example, is unclear. We need to get used to dealing with uncertainty.

It is important for Europe and for Germany not to react to the first announcement by Trump, but rather take the time to see what will be enacted and then decide an approach. The EU will try to formulate a package that can smoothen the situation, such as ramping up defence spending or buying more U.S. LNG [liquefied natural gas].

We know that the competitiveness gap between Europe and the United States in the coming months is likely to widen. Energy prices in the United States might actually decrease over the next few years because the country could decide to produce more oil and gas.

The reaction should not be to mimic the policies of Trump, simply because Europe is not rich in oil and gas. There is no point in Europe declaring that fossil fuels are the solution to competitiveness issues.

Instead, the EU needs to double down on the green transition. It is the only way for Europe to get rid of a toxic dependency on volatile and expensive oil and gas.

What is Germany’s role in the EU energy transition?

Germany has been a pioneer in many ways, but it is also facing bottlenecks. Boosting renewable deployment, fast tracking and simplifying the permitting procedures, and ramping up investments in the electricity grids and digitalisation must all be scaled up in Germany and across Europe.

It is important that the largest country in Europe does this with a European approach and becomes a catalytic force for a stronger electricity union. That is Germany’s only chance to structurally lower energy prices for its industries.

One of the biggest topics of the past three years since the energy crisis was Germany's gas supply. Will that continue to be an issue in the next in this new legislative period?

Germany has been at the core of the European gas crisis over the past few years. That is because of its reliance on Russian imports and its lack of a diversification strategy, which was best illustrated by the lack of a single LNG import facility. The country has had an abrupt awakening with the gas crisis after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In a short period of time, Germany had to compensate for what it had not done before, for example building LNG terminals. This came at a very high cost. Today, Germany is more resilient and has benefited from European solidarity over the last three years. This shows the value of an Energy Union.

Germany has in the past been seen as an anchor of stability in Europe and globally. Is that still true today?

It is no longer as true as in the past, because the model of getting cheap Russian energy to manufacture goods which would be exported to China and elsewhere in the world, while having the security guarantees of the United States, no longer works. In addition, the country’s superiority in a number of technologies is also being put in doubt, starting with the automotive sector. That is the key challenge for the next years, and we can already see this in the current news from Volkswagen.

The big car makers in Germany did not have the foresight to capture early on the electric vehicles revolution and use it as an opportunity for them to transform. They have been focusing on the perfection of the internal combustion engine, while the Chinese have been basically building a new industry at a scale that is difficult to compete with.

What must Germany do?

Germany must not be afraid of transformations. There is a certain tendency to maintaining the status quo, but that is a strategy doomed to fail. Focusing on preserving the status quo in a world that is changing at speed is a recipe for failure. Transformation needs to be embraced.

Germany must ask itself what are its comparative advantages? Maybe there is no business case for the energy intensive industries that are there today. Maybe some of them will have to relocate or just build new factories in other countries, including in the so-called Global South. That is probably where there is better renewable energy potential, lower costs for labour and so on and so forth.

Germany could import intermediate products that can still be finalised in the country, so that the higher added value production process might be retained. It requires a new international strategy to build partnerships – from raw materials to refining and processing to intermediate products. Germany must make sure that it is part of these new supply chains of the future, be it for green chemicals, green cement or green steel.

Even without the pressure of our climate targets, the transition is happening. Many of these changes have developed their own legs even without climate policy, because it is a technological revolution.