Vote25: Mixed climate legacy of Scholz’s collapsed coalition leaves challenges for next government

The collapse of chancellor Olaf Scholz’s government in early November suddenly broke the coalition that entered office roughly three years earlier with the commitment to put Germany's policy in line with the targets of the Paris Climate Agreement. The sacking of finance minister Christian Lindner by the chancellor, which cut the three-party alliance’s reign short by more than half a year, will now be followed by snap elections on 23 February. It also left the country with a raft of unfinished policy business.

The break-up of the so-called ‘traffic light coalition’ of Scholz’s Social Democrats (SPD), the Green Party and Lindner’s Free Democrats (FDP) hit the country amidst poor economic forecasts, the looming threat of a recession, and factory closures and mass layoffs in key industries. It also came against the backdrop of intensifying security challenges related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and deep uncertainty over an incoming Trump government and its potentially disruptive stance on trade, defence, and diplomatic conventions anticipated in many European capitals. All of these challenges also require resolute responses in energy and climate policy – but questions over funding ultimately led to the coalition’s early end.

“The coalition’s break-up is threatening much-needed progress in several areas,” Brigitte Knopf, head of think tank Zukunft KlimaSozial, told Clean Energy Wire. Knopf, who also co-chairs the government’s Council of Experts on Climate Change, said that the snap election might exact months of uncertainty and possible U-turns in important policy areas. “It is likely that we are facing a difficult period until about mid-2025, so there will be about half a year of standstill in policymaking,” Knopf warned, arguing that this could take a toll on acceptance of the energy transition and significant planning insecurity for companies preparing decarbonisation investments.

The crises that handicapped coalition’s climate ambitions from the outset

Economic conditions were far from ideal when the so-called ‘traffic-light-coalition’ (named after the parties’ respective colours) entered office at the end of 2021, as the European energy crisis began to surface in the wake of an ebbing coronavirus pandemic. Despite these odds, the newly formed coalition managed to agree a government programme to champion climate action, including a commitment to put the country on an emissions reduction path compatible with limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. It also included a pledge to establish Germany as “social-ecological market economy” through massive investments in future industries and the rapid buildout of renewables.

Less than three months into its term, the Russian invasion of Ukraine then shattered the traffic-light-coalition’s priorities, forcing it into damage control and a strategic pivoting in energy policy. Encapsulated by Scholz’s announcement of a ‘Zeitenwende’ (turning of the times) in Germany’s stance towards Russia, the country’s most important energy trading partner fell away and had to be replaced with alternative import sources, with fossil gas at the centre.

Green minister Robert Habeck’s economy ministry was in the spotlight during the energy crisis, and he oversaw a wide array of crisis response measures, including new gas storage regulations, the fast-tracked construction of liquefied natural gas (LNG) import infrastructure, a temporary re-activation of coal-fired power plants, a three-month delay of the nuclear phase-out as well as several energy price support schemes for households and businesses.

The government’s immediate crisis response was widely seen as a success. “The coalition’s early end must not overshadow the fact that this government has made many important decisions that will accelerate the energy transition and make our energy supply more secure,” Kerstin Andreae, head of the German Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW) told Clean Energy Wire.

The country managed to avoid supply disruptions and pulled off a complete shift in its energy supply while installing a range of protective measures to avoid social hardship and company bankruptcies. “Together with the energy industry, the government has made sure that Germany proceeded safely through the energy crisis and that supply security was always guaranteed,” she argued.

Coalition leaves mixed legacy in sectoral transition progress

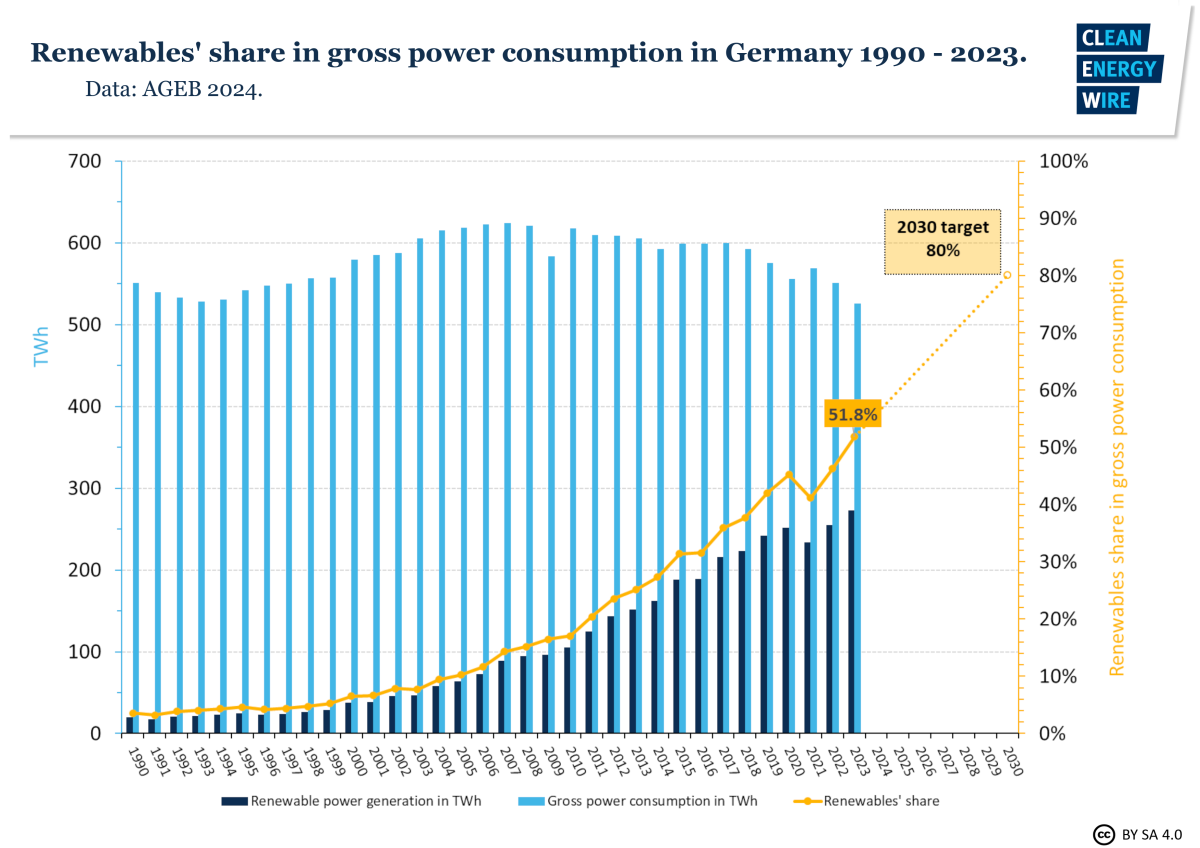

At the same time, Germany’s emissions dropped about ten percent in 2023 and the country for the first time was deemed to be largely on track to reaching its national target to reduce total greenhouse gas emissions by 65 percent by 2030. Aided by a boost in popularity for renewable energy sources amid the fossil fuel crisis triggered by Russia’s war, Habeck’s ministry also pushed for the sharp uptake in the expansion of renewable electricity: from about 41 percent of electricity consumption in 2021 to more than half in 2023, bringing the government’s 80 percent target for 2030 into reach. At the same time, coal power use dropped to the lowest level in decades.

Does that mean the outgoing coalition has been a boon for climate action after all? “That depends on which sector you look at,” said think tank head Knopf. While there has been visible progress regarding the electricity system, “in the buildings or transport sector, too little is happening still,” she added.

In the transport sector, the introduction of the ‘Germany ticket’ for using local public transport across the country at a flat rate was among the most visible achievements. But the popular scheme was hampered by funding disputes since its introduction and its continuation beyond 2025 is uncertain, while the extent of its impact in reducing emissions has so far been ambiguous. Likewise, plans to massively increase investments in railroad infrastructure have also been thrown into turmoil by the debt brake fallout. In the roll-out of electric vehicles, the government’s target of 15 million EVs on the road by 2030 is projected to fall short by six million cars at current rates — while the roll out of charging infrastructure is also not on track.

In the heating sector, an initial boost to heat pump sales subsided in 2024, pushing the coalition’s goal of six million units installed by 2030 further out of reach. From 2024 onwards, the coalition aimed to have about 500,000 heat pumps installed annually. According to heating system industry association BDH, however, only about 200,000 units will be sold by the end of the year.

Moreover, the emissions drop was also at least to some extent caused by economic stagnation and a substantial decrease in industrial output. While Germany’s industrial blight is not solely the fault of the government, the coalition still had to deal with a constant stream of bad economic news throughout its term. Despite a multitude of initiatives to revive industrial production and investor optimism, captured well by two industry summits infamously held in parallel by Lindner and Scholz on the eve of the government collapse, the coalition leaves behind an economy fearful for the survival of core industries and many citizens who are anxious about their jobs and purchasing power.

On climate policy, however, the government made good on promises to better integrate it as a cross-sectoral task for the government, including in security and foreign policy. Likewise, a national water strategy and a strengthened role for natural climate protection complemented the more holistic approach promised to combat global warming and cope with its effects.

However, Scholz’s key climate diplomacy project, the “climate club” initiative for deepened cooperation on sustainability policies in trade and production, did not figure prominently in government policy after the scheme was adopted at the G7 meeting hosted by Germany in 2022.

Debt brake ruling over climate and transformation funds broke government’s back

The largest blow to the coalition government’s ambitions came in November 2023. A lawsuit filed by the main opposition party, the Christian Democrats (CDU), with Germany’s highest court resulted in the judges prohibiting the government from reallocating billions of unused funds, originally earmarked for the country’s pandemic response, for use in its Climate and Transformation fund (KTF). The ‘debt brake’ ruling pulled the plug on many of the government’s projects, leaving it scrambling to reshuffle funds to at least finance the most important energy and climate policy measures, opening the stage for endless dispute over funding that would ultimately prove fatal to the government’s survival.

In the 2025 Climate Change Performance Index published by NGO Germanwatch, the country fell two spots, ranking 16th and thus well behind neighbouring European countries. While the authors assumed that Germany will “at least get near to” achieving its 2030 climate targets, they noted that the ongoing rows over funding key climate and energy policy measures make the long-term outlook gloomier and ultimately could “lead to a larger emissions gap.”

Ottmar Edenhofer, head economist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) told newspaper Tagesspiegel that the coalition’s track record had been a “disappointment,” given the high hopes the three-party-government had raised when entering office. The government failed to compensate the loss of its financial clout by working towards a more structural and European approach that creates incentives to shift investments, he argued.

Vote25: 2030 climate and energy targets hinge on next German government

Despite the success in strengthening central pillars of the energy transition and making first inroads to tackle laggard sectors such as heating – illustrated by the controversial debate around the country’s Building Energy Law, which ultimately was adopted in a trimmed-down version – Germany’s Expert Council on Climate Change said decisive steps are still lacking. This included measures such as tackling fossil fuel subsidies and a general “consistent concept” for reconciling emissions reduction with social acceptance.

Instead, changes to the country’s Climate Action Law by Scholz’s government rather took pressure off individual sectors to continuously improve their emissions balance by looking at progress in total emissions. The changes were heavily criticised for watering down responsibilities. Environmental NGOs filed a constitutional complaint against the amendment, arguing it would undermine fundamental rights of future generations by hindering effective policies for reaching a climate neutral economy by 2045.

Coalition’s collapse unlikely to make next government’s job easier

Key instruments devised by the government to assist companies in mastering the move to climate neutrality in a challenging international market environment hang in the balance. This includes economy minister Habeck’s ‘climate contract’ scheme to support flagship decarbonisation projects in industrial production as ongoing budgetary uncertainties could block the auction for new contracts. While there is great interest in auctions that award the billions of euros to the most promising ideas for reducing carbon emissions in areas such as steel, cement, or glass production, the government collapse will likely cause significant delays at least. Likewise, a government strategy to better integrate carbon capture in industry transformation and climate policy has been held up by the coalition’s collapse.

A deal Habeck brokered with the CDU-led government of western coal state North Rhine-Westphalia includes the end of coal-fired power generation in the western industry region by 2030. However, given the delays in providing for secure alternatives to coal power, and ongoing resistance to an earlier phase-out than the official 2038 deadline by eastern state governments, the coalition’s plans to “ideally” achieve a nation-wide coal exit by the end of this decade hang in the balance. A planned evaluation of the coal exit’s progress fell flat and due to the government’s collapse will not be made before mid-2025.

The next government, which is scheduled to remain in office until early 2029, will now have to oversee efforts taken to ensure a stable coal-exit path and to close the remaining gap towards the 2030 emissions reduction target.

The development of the European emissions trading system (ETS) will therefore loom large on the next government’s agenda. Price rises in the ETS could reshuffle the calculations of coal plant operators and make plants economically unfeasible quickly. At the same time, the inclusion of heating and transport in a reformed ETS by 2027 will affect many citizens directly.

Ideas flaring up among industry representatives to question Germany’s 2045 target that some policymakers could find appealing to pick up would also be upset by the ETS, said Germany’s chief energy transition progress evaluator Andreas Löschel. The researcher at Ruhr University Bochum explained that current ETS rules set a path for climate neutrality around that year, making the question "unsuitable" for political strategy.

Comments from some leading figures of the conservative CDU, which is currently leading in the polls, and industry lobbyists, question Germany’s goal to reach climate neutrality by 2045 and thus before the overall 2050 EU-goal, creating fresh uncertainty over the country's climate ambitions. A Europe-wide surge of right-wing populists who have shown little interest in climate action, which they often brand as "elitist", is adding to doubts over the continent's climate pledge - and has also overshadowed three consecutive state elections in eastern Germany in the traffic light coalition's last months.

The next government will have to devise a transition from the national to the European carbon pricing system for transport and heating fuels and decide on compensation mechanisms such as the promised ‘climate bonus’, which the traffic light coalition never implemented despite initial pledges to do so. “Affordability currently is the dominant topic,” said researcher Brigitte Knopf. “That’s where policymaking needs to intervene,” she argued, adding that a new government, possibly led by the CDU, would likely address a reform of the debt brake after all.